In Dreams — Mystical Landscape Photographs by Petros Koublis

34 year-old Greek photographer Petros Koublis (we already featured some of his work here) discusses In Dreams, his new series of stunning landscapes, and the deep ideas that inspired and influenced this body of work – from Greek mythology to Neoplatonist philosophers.

Hello Petros, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Photography for me is like an impulse, a spontaneous process. It has to do with what my soul can easily relate with: it’s about what attracts my emotions rather than just my attention.

For some years now I’ve been avoiding making images of urban environments or that include any references to the human element, but such a choice doesn’t really have to do with photography at all. I think it’s more the consequence of a natural change that’s occurring inside me: I am driven more and more towards time-independent patterns, and free from any attempt of documentation. I’m using photography to challenge the authority of the mind over our reality. My photographs don’t provide proofs – they are sensual objects. I don’t care so much about how the world looks like, but what it feels like.

What is your new series In Dreams about, in particular?

It is about the experience of perceiving the world through our intuition. Logic and reasoning were a revolution that changed the course of our spirit’s evolution, yet on their own they were never able to explain some of the most precious aspects of the human experience – things like love, compassion and solidarity.

An evaluation of our world could lead to negative conclusions, as we can see that in many ways our society is not aligned with the achievements of our spirit; in so many cases it feels as if our societies were left behind into an obsolete and dysfunctional state. The Western world tries to hide the inequalities and its social collapse under the blesses of a widespread consumerism, while a great part of the rest of the world still struggles in the deep oceans of anachronism. With In Dreams I tried to embrace a world that challenges the authority of reason in the continuous drama that so many people are going through around the world. As long as there are people suffering, we will never be able to claim that reason has prevailed.

Dreams have a gentle effect: they address our sensitive side. Somehow, they speak to the innocence of our childhood, when things were defined mostly by imagination rather than logic. So maybe the dreams we had as children can question the reality we live as adults, and show us the way to a better future. In this sense, I consider In Dreams to be close to the aspirations of the Romantic movement, aiming at the restoration of our ideals through our senses.

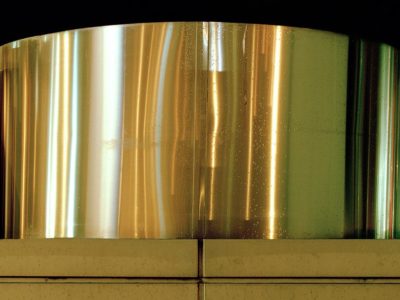

Looking at the images of In Dreams one gets a keen feeling that you’re using real landscapes to create an unreal, mythical world. How would you describe that world?

Reality is shaped by the accumulation of all the ideas and definitions that concern any thing and any concept surrounding us in our lives. We will never be able to look at the sun or the stars the same way our ancestors did, because neither the sun nor the stars have the same meaning for us that they did for them. Their approach was more sensual and emotional, permitting their spirit to reach higher religious experiences; while our perception, being based on the foundations of reasoning, is leading us higher towards the ideas of philosophical liberalism and progressivism.

But what if there were no definitions and everything was, once more, open to interpretation, just like everything was open to be interpreted in a new way over and over again through the centuries and the millennia? The landscapes I collected seem to have this uncertainty inside them. Even though we are able to recognize the subject, at the same time we feel that there’s something else going on under the surface. Somehow this is the foundation of Mythology. This mystical, transforming activity that takes place below the nature of things, influencing their form but keeping its own hidden from our eyes. We don’t have to see this activity in order to witness it – we only have to sense it.

Animals play an important role in this series. Can you talk a bit about making the photographs where animals appear, and why did you decide to include them in the series?

I feel deeply connected to animals, perhaps because both of my parents are veterinarians and I spent my whole childhood around animals. I feel comfortable being with them and I like to observe their behavior. I have the patience to wait until they accept my presence, and I always try to establish a relationship, as brief as it may be. Then, it’s almost natural for me to photograph them. I approach animals as if they were the single thread that still binds us to nature; as if through these wandering creatures, we are led blindly through a landscape that otherwise seems impenetrable.

Did you have any specific reference or source(s) of inspiration in mind while working on In Dreams?

It was some time before I started editing this project that I ran across a book written by Artemidorus Daldianus, a Greek diviner who lived in the city of Ephesus during the II century A.D. The book’s title was Oneirocritica – it’s about the interpretation of dreams. It’s a rather interesting book that became a point of reference for many contemporary authors, from Sigmund Freud to Michel Foucault, and it was extensively studied by psychologists during our times. I already had a great interest about the philosophical works of that period, and especially Neoplatonism. I find Neoplatonist ideas to be thrilling, mostly because of how they blend science with mystic interpretations and other obscured allegories over the human experience – they provided a great foundation for me to reflect further on the boundaries between the perceptible and the ineligible world.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

The experiences I accumulate in my life are the ones that chiefly define the form and content of my work. I let my work unfold naturally without the interference of conceptual references. I’m mostly influenced by the way we interact with Nature, in a cosmological sense, through the eons. I am always fascinated by the mythologies of different cultures around the world, though my main interest and profound devotion is for Greek mythology.

I don’t approach these texts as the desperate efforts of long-gone societies to explain the unknown, but as an overview of the human experience, the seeds of language, poetry and art, the revelation of philosophy and the humble origins of science. It’s about the manifestation and praise of beauty. In fact there is a Cosmological aspect to the nature of beauty, which I find to be accurate. Cosmos, the word that refers to the universal order, is a Greek word that shares the same origin with the word kosmima, which stands for jewel; both come from the word kosmein, a verb meaning “to arrange, to set, to decorate, to make something beautiful”.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Bryan Schutmaat, Cody Cobb and Drew Nikonowicz, to name just a few.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Stillness. Silence. Peace.

Keep looking...

Natalia Ershova Photographs “Modern Hermits” Who Live Their Lives Inside Their Homes

See Ciro Battiloro’s Lyrical Portraits of the People of Sanità, a Deprived District in Naples

Matija Brumen’s Nocturnal Photos Transform Ordinary Urban Objects into Fascinating Sculptures

Abendlied — Birthe Piontek Documents the Impact of Her Mother’s Dementia on Her Family

Enter #FotoRoomOPEN for a Chance to Have Your Work Published by Void

FotoFirst — Alex Huanfa Cheng Has Been Taking Intimate Photos of His Partner Zhiyu For 6 Years

Federico Aimar Found 900 Photos Shot in the Early 20th Century in Abandoned Mountain House