Into the Classrooms of the Last Nenet Children to Live Nomadically

31 year-old Japanese photographer Ikuru Kwajima talks about Tundra Kids, a series of lovely portraits he took in a unique school at the Arctic Circle where children belonging to the nomad population of the Nenets settle down during the winter and are introduced to the Russian modern-day lifestyle.

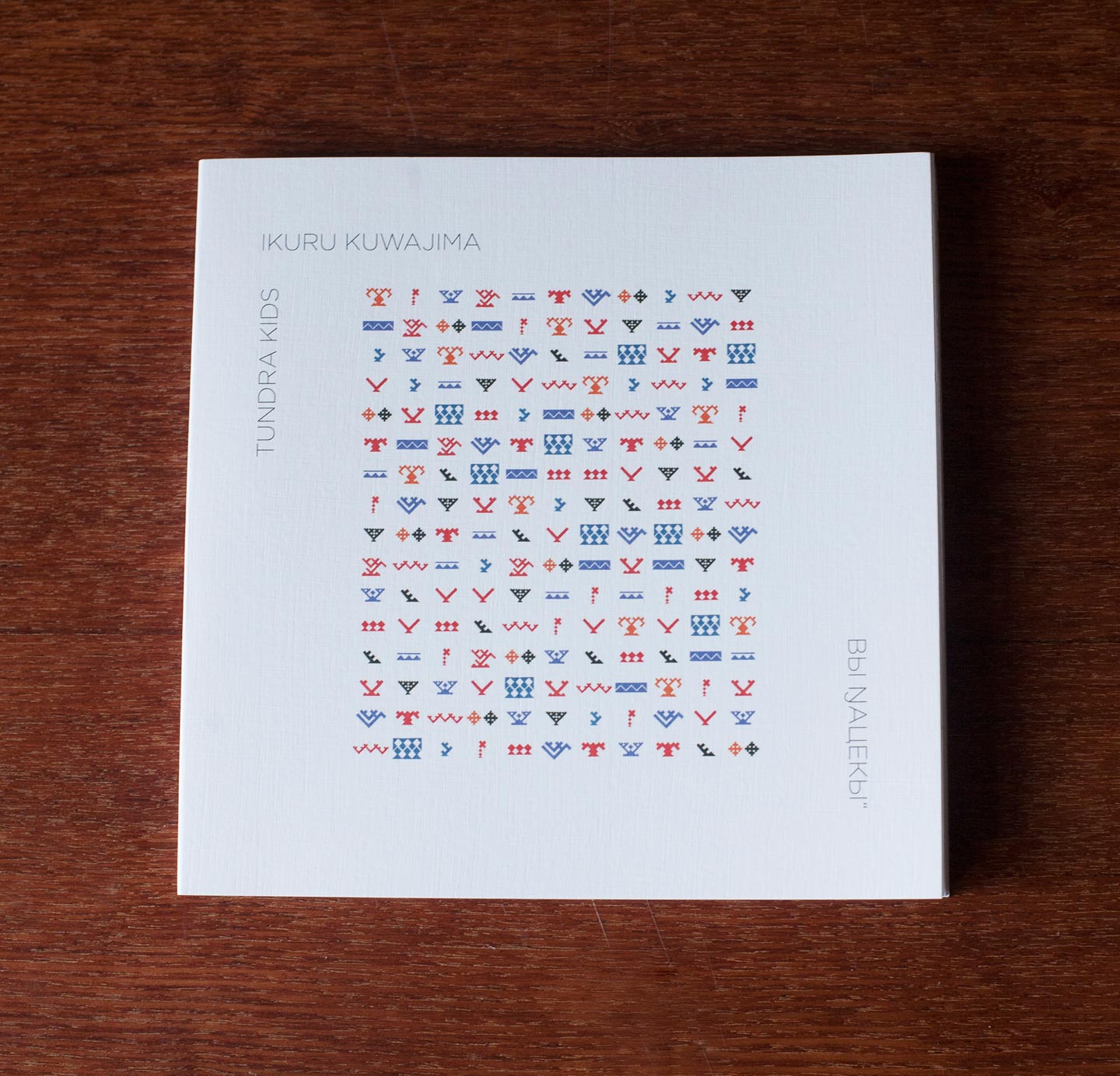

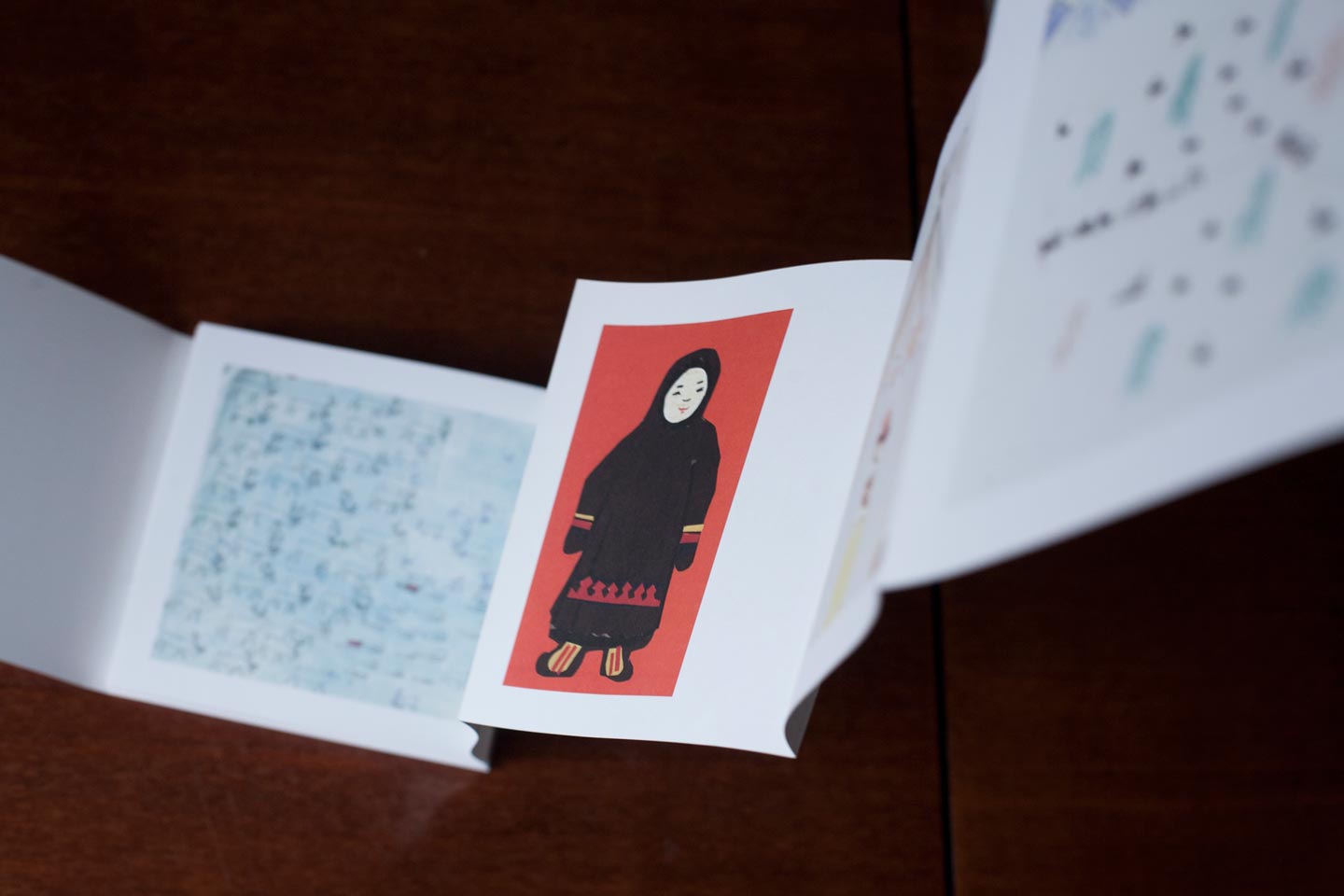

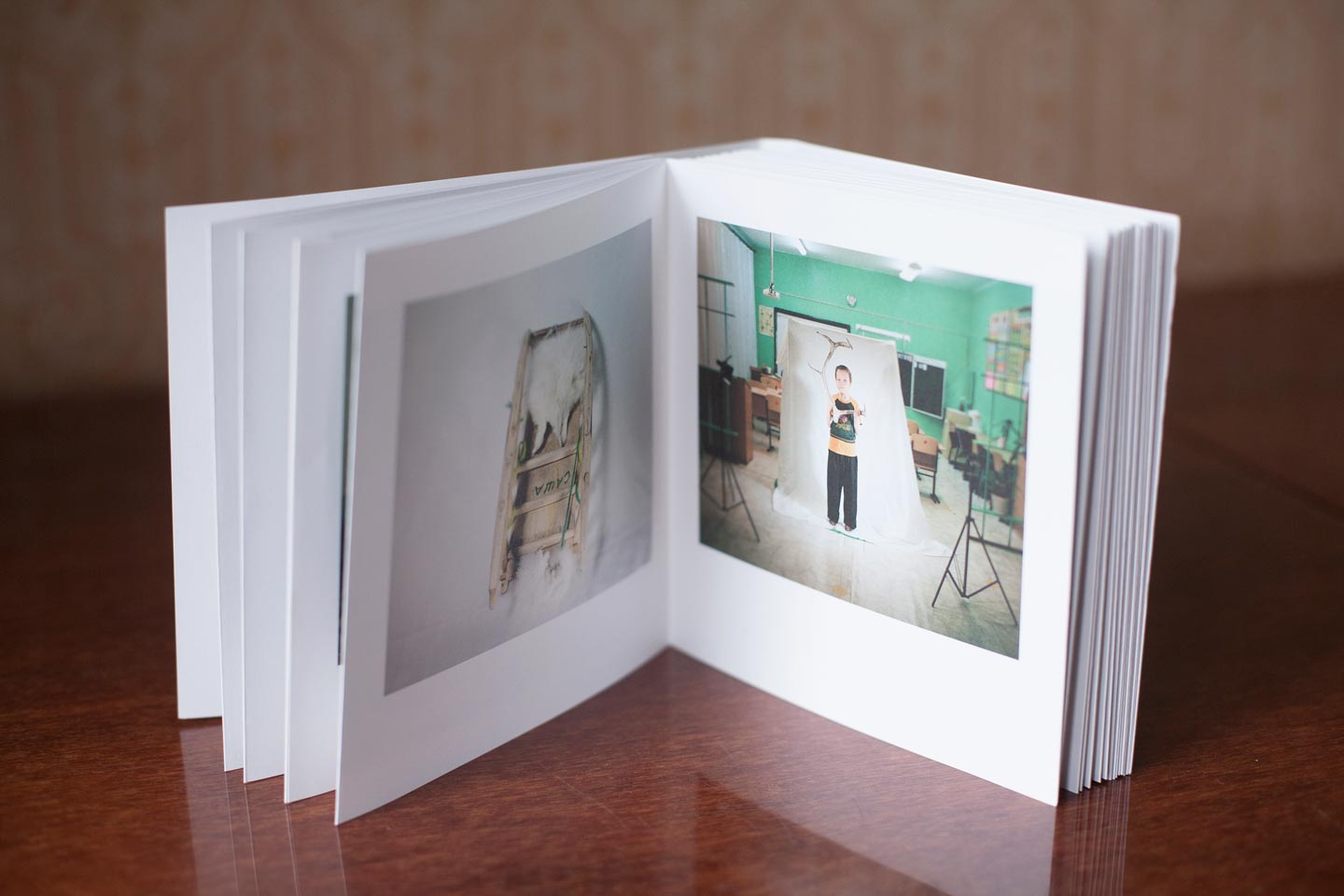

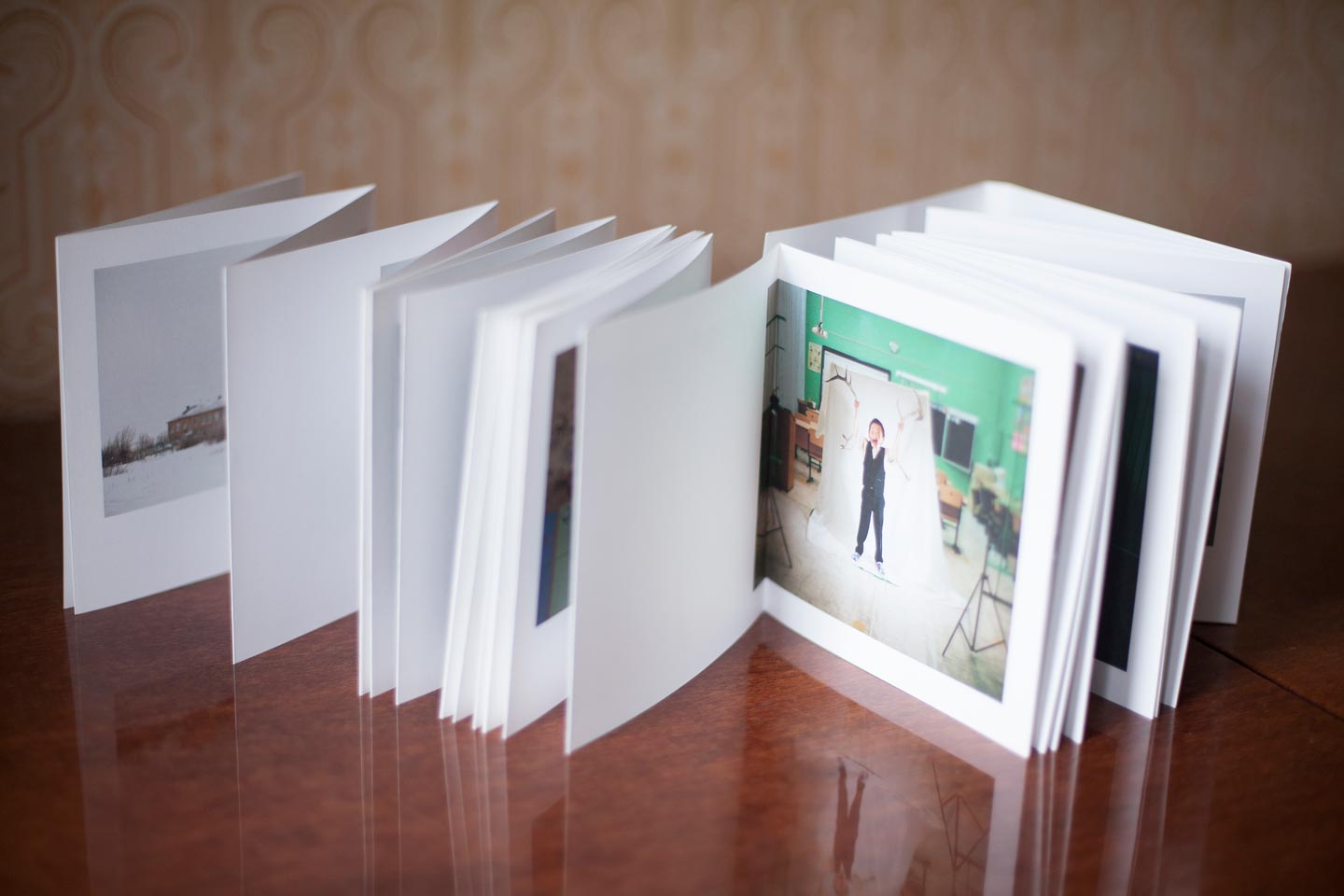

Tundra Kids is available as a leporello photobook (see below for a few pictures) published by Schlebrügge.Editor. The book mixes the portraits with scans of the children’s drawings and photos of their toys – buy your copy here or here.

Hello Ikuru, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I am a curious person, and I love photography because it allows me to learn about new places and cultures. I studied journalism, so I often think in journalistic terms when I choose the subject matter for my projects; but, I always try to work on topics that few people would work on. I don’t see the point in covering news that attract tons of other journalists, while I think it’s important to diversify information and throw light on under documented realities. Plus, I’m claustrophobic and don’t like overcrowded places.

I also like the freedom of working independently and taking approaches different from straight photojournalism. For instance, about a year ago I started working on book-making, and I really enjoyed it: it allows me to work beyond the constraints of the photographic medium.

For Tundra Kids, you photographed the Nenet children of a boarding school in Vorkuta, in the north of the Arctic Circle. Please tell us more about both the Nenets and the school.

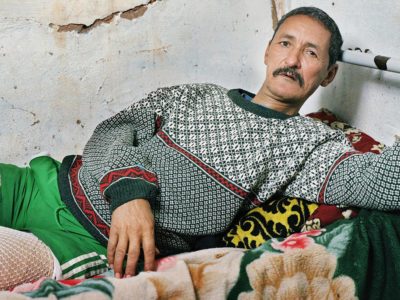

The Nenets are one of the major indigenous minorities in Russia’s north. Although parts of the Nenets population have been moving to cities and adapted to the modern and settled lifestyle since the Soviet era, a lot of them still roam the freezing tundra. But now, most kids from the nomadic families are sent from the tundra to boarding schools in populated areas, where they learn Russian and get introduced to the modern Russian society through the schools. In other words, the modernization of the Nenets, as a whole group, has been speeding up in the past years, leading more and more of them to settle down.

Switching from a nomadic to a settled lifestyle one causes a major loss of the Nenets’ identity, which is founded on nomadism. So, the boarding school is sort of a turning point not only for the children but also the Nenets as a group. In the boarding school, you can observe various cultural collisions – in the children themselves, in their drawings and toys and in the school’s interiors, which are decorated with a Nenet theme, including the mobile tents used in the tundra. With this project, I wanted to put a strong emphasis on this changing, ambivalent state of these children and the Nenet identity in a globalized world.

Tundra Kids differs a lot from other reportages we see about nomads in general…

I agree with those who critique the media saying that it often amplifies the public opinion rather than informing on something new and worthwhile; or that photojournalism overly dramatizes an event by portraying the subjects in a certain light and composition. There is also debate around the normal savage, that is the depiction of indigenous people as wild and uncivilized – I think the problem is the shortage of diversity in the forms of representation rather than the single reportage or story.

In the specific case of the Nenets, in the media they are mostly presented in their traditional garments crossing the snowy tundra by reindeer, and this is partly due because it’s such a ‘photogenic’ image. But there is another side of their reality: not all the Nenets have reindeers, and their lifestyle has been changing a lot. I thought the school would be a more interesting environment and could offer a portrayal of the Nenets from a different perspective.

Can you talk a bit about the lovely portraits included in the book? How did you interact with the children and what did you ask them to do?

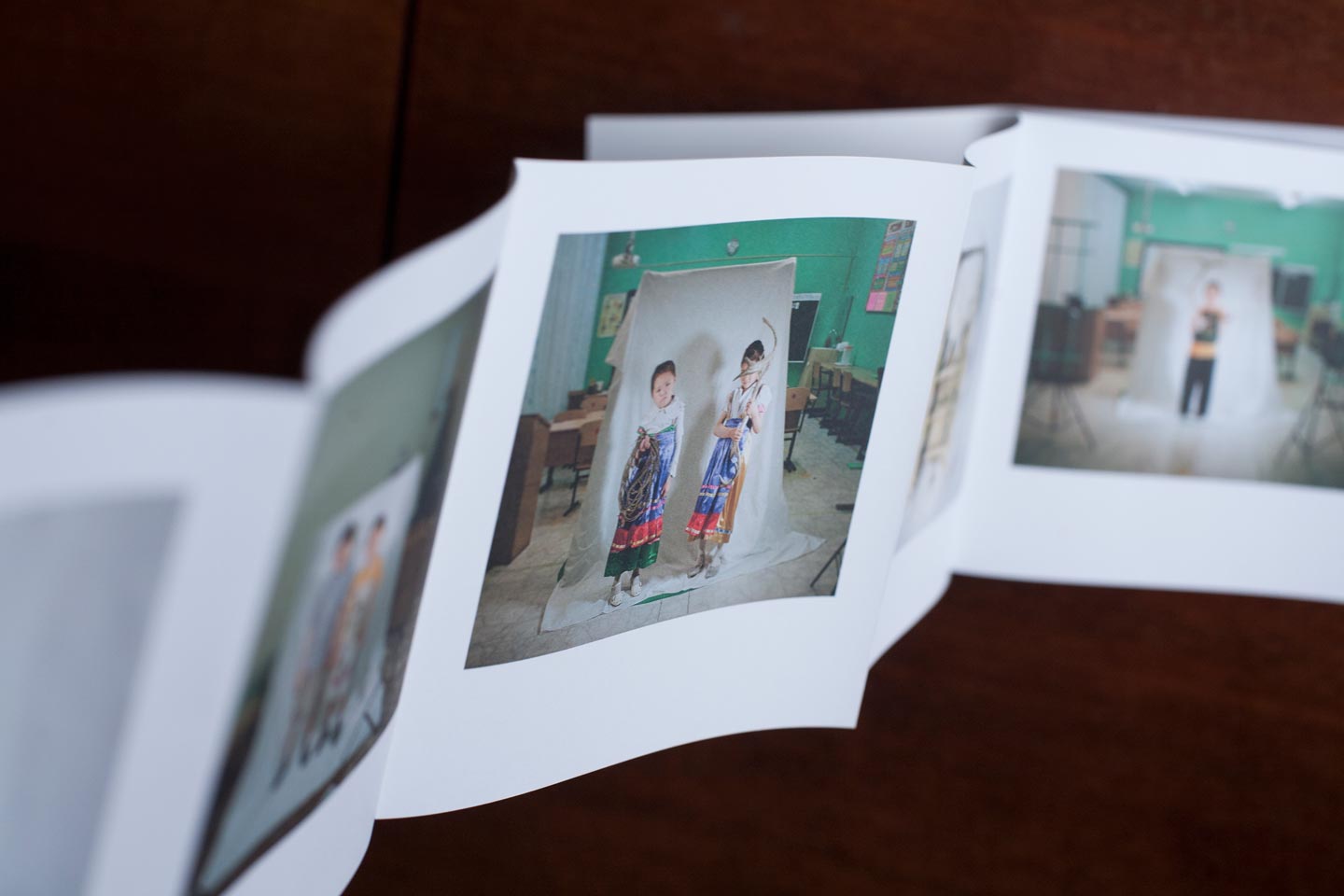

There weren’t any communication problems because we could directly speak in Russian. I set up the background and light beforehand and mostly asked the students to just stand in front of the camera. In some cases, I asked some of them to hold the light and included them in the frame. When the teachers were present, it was a bit easier to work because the children were more obedient. But if the teachers weren’t paying too much attention to the shoot, some children would start playing with the camera and me, running around the room and playing with my gear… In those cases things got more complicated, but it was pretty fun. The girls were very shy, it was harder to interact with them; the boys were generally friendly, in fact sometimes they were so friendly that they started playing with me!

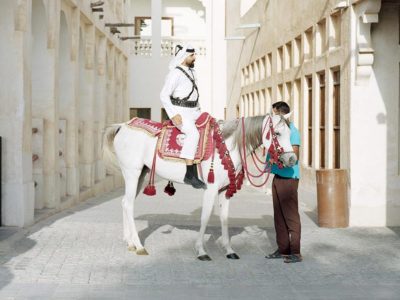

The portraits were all taken in the school’s classrooms, which you transformed in photo studios for the occasion. Why, despite using a backdrop and artificial lights in many cases, did you decide to step back and keep the class in the frame?

Imagine plain pictures of Nenet kids studying in the rooms of their school – that wouldn’t be visually so interesting, as the photos wouldn’t look much different from similar images of kids anywhere in the world.

The main theme of this story is the collision and blending of two different cultures: the use of the backdrop and artificial lights indicates the existence of these two worlds. For instance, the traditional clothes the children wear in some portraits reveal their Nenet background, while the modern environment of the classroom references the Russian culture. Framing wider to include what was behind the backdrop also works as a symbol of how our perceptions are often erroneously based on how we see things, neglecting what there might be beneath the surface.

Another reason to keep the backdrop and lights in the frame was to immediately show viewers that they’re looking at a staged photo: the artificiality of the set up adds to the modernity of the classroom, emphasizing how the kids’ garments represent a tradition that is being lost.

How do you hope viewers react to your portraits?

I hope viewers wonder why the portraits were shot that way and notice the different layers of the pictures. I hope they realize the complexity of being a Nenet today and how globalization is spreading so far as northern Russia, and that they ask themselves whether this is a good or bad thing, because I myself am not sure about it.

The Tundra Kids book also includes photographs of toys and drawings made by the children. What is the function of these images?

The kids of the boarding school are nostalgic about their nomadic life. They may physically be in the school, but their thoughts often go to the tundra. Their drawings and objects are visual extensions of such thoughts, of what they see in their minds. I scanned them and put them in the book so that the project could not only show the physical space they now inhabit, but also their mental space and the gap between the two. Also, I think the drawings, objects and pictures work well together and create a harmony. The book form was most appropriate for Tundra Kids. In the book I also included a sort of Nenet fairly tale which symbolically tells the history of the Nenets and represents another important part of the work.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Tundra Kids?

It’s hard to pin down any specific references because my ideas came from various sources: readings of media critics, philosophy and contemporary art texts, visits to arts exhibitions and my own disappointment with photojournalism. At that time I was also taking a distance learning course of contemporary photography by Fotodepartament, a St. Petersburg-based photography institution that provides, which helped me define the confines of my project. Finally, a few Russian photographers like Yulia Borissova and Petr Antonov gave me good advice on the design and form of the book.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

I’ve been mainly influenced by classic, modern and contemporary literature, especially Russian and European. I’ve also read a lot about philosophy and contemporary arts. Last but not least, years of living in post-Soviet countries has also shaped my vision.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

I like Michael Wolf’s works a lot.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Silent. Remote. Bizarre.

Keep looking...

Land of Plenty — Marco Barbieri Photographs Doha as a Still and Empty City

Rick Schatzberg Juxtaposes Photos of His Friends When They Were Young and Now in Their 60s

State of Identity — Milan Gies Portrays Young People Transitioning Gender

FotoFirst — Juan Orrantia’s Color-Rich Photos Visually Interpret His Experience of South Africa

Bitter Sweet Soft — Bernat Millet Photographs the Saharawi People and Their Life in Refugee Camps

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Calls for Entries Closing in September 2019

Gian Marco Sanna Creates Images Inspired by the Esoteric Legend of an Underground World