This World and Others Like It

In his intriguing series This World and Others Like It, with which he recently won the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize, American photographer Drew Nikonowicz reflects on what exploring the landscape means in the 21st century, a time when technology allows us to be “anywhere in this world, and anywhere in many other worlds” despite sitting in the comfort of our own homes.

Hello Drew, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Thank you for inviting me! It’s a pleasure. My primary interests as a photographer are arguably the same as my primary interests in general. Photography is seated in the center of this list. It is an exceptional combination of science, engineering, and language. When used intentionally, it can sometimes add up to something great. Photography is also interesting because it is very often thought of as a mechanical process, and yet its uses are immensely diverse.

When it is working, my photography acts as a way to exercise out a specific idea or piece of a larger answer to your question.

This World and Others Like It mixes authentic landscape photographs and digitally rendered scenery. What was your intent in creating this series?

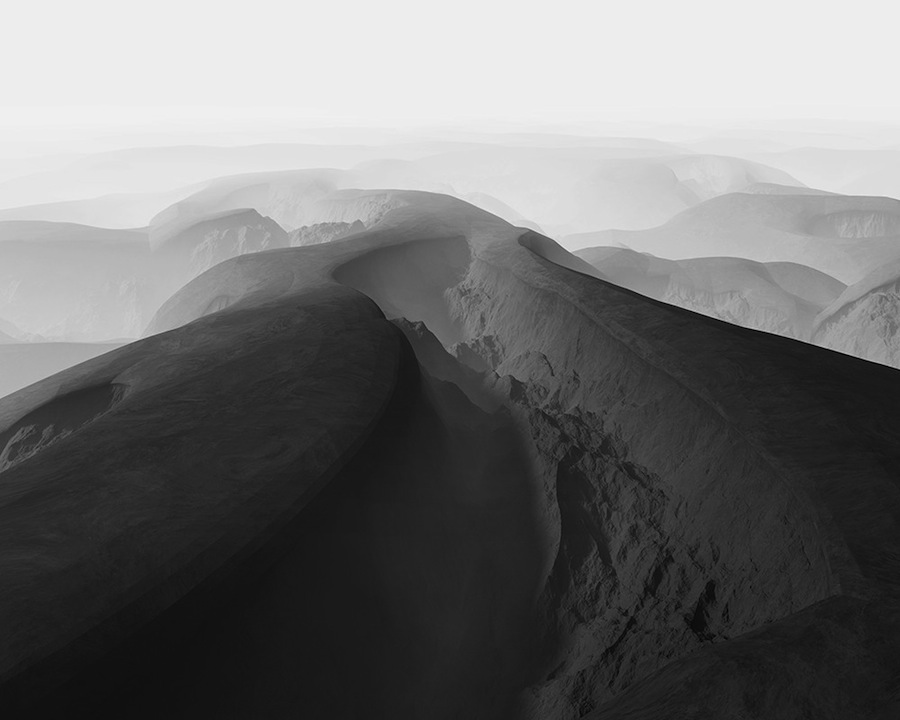

At the end of my statement for this work I say, “This suggests that now the sublime landscape is only accessible through the boundaries of technology“. We live in a world where I can go anywhere from where I sit right now. Anywhere includes anywhere in this world, and anywhere in many other worlds. One of technology, exploration, the landscape, and all of these things intertwined.

I recently saw a photograph of a boy from the first time he saw the ocean made by his father. Was this truly the first time he had seen an ocean? We now have instantaneous access to most everywhere, which complicates our ability to have a genuine experience.

How did you get the idea for This World and Others Like It?

I don’t think there was a very precise aha moment. I also do not think there was a distinct moment that I started working on the project. I have had the ideas for this series long before I knew photography. Similarly, the work existed before I had given it a name. As I learned to use photography as a language, I started to write clearer and clearer sentences. Eventually, through photography, I found my way back to the ideas that always interested me, and now I was equipped with the photographic language as a tool to describe it.

The sequence keeps jumping from wide vistas to studio portraits of rocks, for the most part. What’s the function of the latter type of imagery?

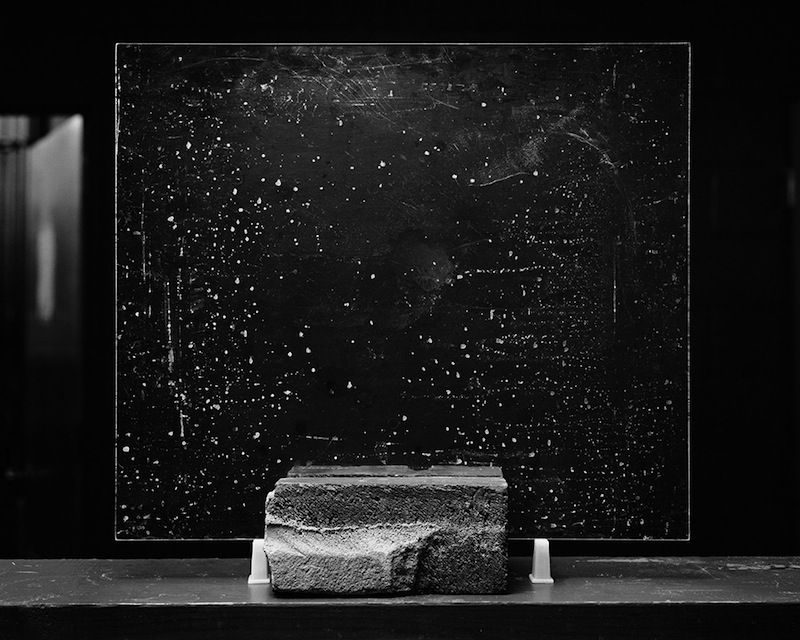

The studio rock studies take on several roles in the series. First, there is a suggestion that these materials are the building blocks which create the vistas. Other images in the series reveal my hand in the process, suggesting my presence in curating the images. This is related back to the studio rock studies as it references another kind of fabrication or creation. In this regard they also function as a way to show how our experiences are mediated: by me with my camera, by a very precise placement of rocks and materials to create a scene, or perhaps by a defined path which tells you how to navigate a space.

Why did you choose to work with black&white?

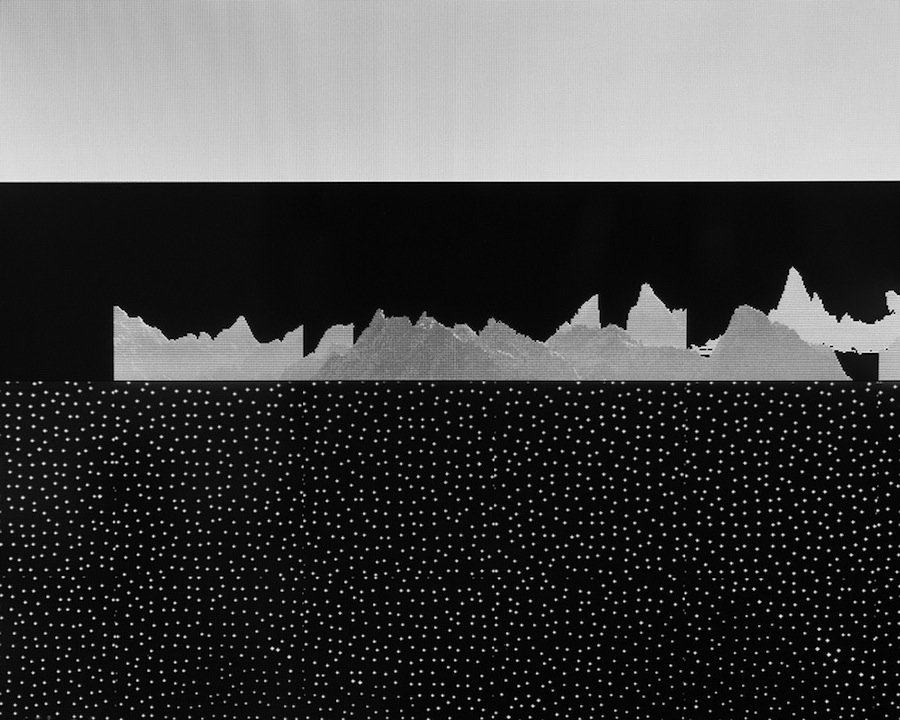

My use of grayscale has several significant functions. For example, when combined with my large-format process, it references the language of 19th century image-making practices. It also allows for many different sources of imagery to share a level playing field. By doing so, computer generated spaces might be considered as photographs and vice versa. However, I am not interested in tricking the viewer explicitly: if the built environments were immediately recognizable as different from the photographed environments, the viewer would not have any time to interrogate their relationship.

Tell us more about this picture.

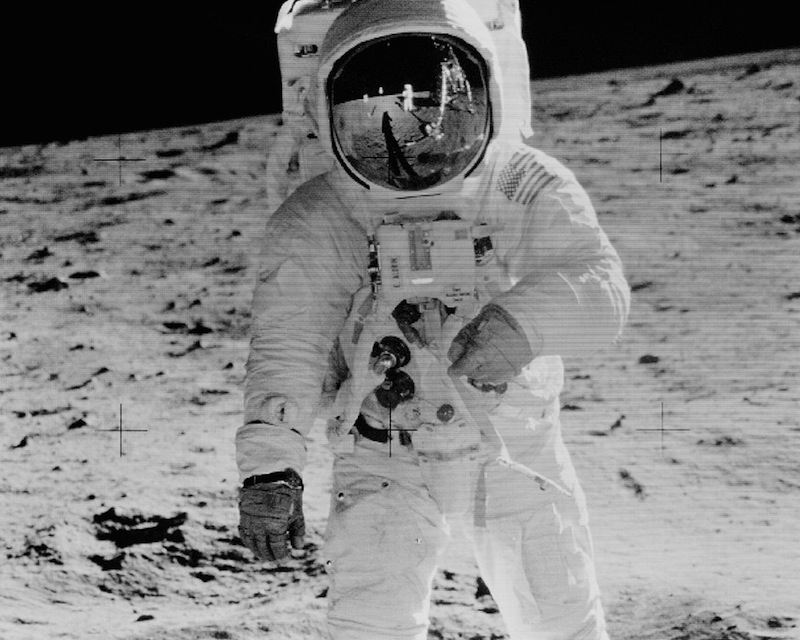

In 1969 after a three day journey through space, two men walked upon the surface of the moon. In that moment, they represented the greatest exploratory achievement that humans had ever completed. Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong were the first men to walk on the moon. Many more came after, but Neil Armstrong’s name is the one that is usually remembered.

If you search Neil Armstrong’s name online, the Google blurb states that he was “the first person to walk on the Moon“. More importantly, he was the first photographer on the moon. It was primarily Neil’s responsibility to document their excursion on the moon. As such, this famous image was made by Neil, it is not a photo of Neil. Instead, it’s a photo of Buzz Aldrin. In his autobiography titled Magnificent Desolationhe Buzz Aldrin poses the question, “What does a man do for an encore after walking on the moon?”.

My photograph of Neil’s photograph on my computer screen is a reference to my thesis which states that the sublime landscape is only accessible through the boundaries of technology. Photographers and explorers alike have become obsolete in the face of technological advancements. Unmanned rovers are now the standard for exploration beyond Earth. These probes and rovers wield cameras alongside drills and other scientific instruments. The camera has simply become another tool in its arsenal.

Is there any image that you consider particularly significant for the work?

The images that mark a shift in my trajectory are significant for me. By this I mean photographs that allowed me to think about my work in another way, or somehow refilled my mind with fresh ideas for the series. For example, the image with two bricks holding up a piece of plexiglass in the darkroom. This photograph was the first instance, chronologically, of me bringing my own process into the content of the photographs.

Outside of thinking about your question in that way, I would argue that each image is important to the series. The sequence I display the work in is an important aspect when thinking about the project. I was very careful to make sure each image contributed something to the sequence and was placed properly within it. If it did not fulfill this criteria, I cut it out.

Did you have any particular reference or sources of inspiration in mind while working on This World and Others Like It?

One of the early influences I had in mind was Joan Fontcuberta’s book Landscapes Without Memory. Some of the ideas he presents in that book were pertinent early on because the project originally consisted of only computer generated landscapes.

Later on, artists like Timothy O’Sullivan began entering my field of vision. Particularly his photographic contributions to The King Survey in the late 1800s. He was much more than just a survey photographer. There is one image in particular of Cottonwood Lake where in the foreground there is a man on a boat. This man is holding another glass plate negative of the same scene O’Sullivan had already shot. Details like this suggest that he was interested in more than simply describing the landscape as data.

Another important influence which comes to mind is Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan‘s book Evidence. Evidence is a collection of images from public and private archives which, when removed from their original context, become scenes which feel impossibly strange. The images demand an authority because of where they come from, but their content instills much doubt in the viewer. This way of thinking about and showing photographs was and continues to be extremely exciting for me.

This World and Others Like It earned you the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize. What kind of emotion was it when you learned that you were the winner?

I was blown away when they announced the shortlist, and again when they announced me as the winner a month later! I had to read the email several times for it to sink in that I had won. The height of my excitement was seeing that the series, independent of explanation, communicated the ideas which I had hoped it was effectively delivering. It has been an extremely exciting and encouraging time.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

The nature of the world today is amazing because I have the privilege to view so many great artists making exciting work through the internet. Some of my favorite photographers right now would include (alphabetically) Caleb Charland, Joan Fontcuberta, Martin Hyers and Will Mebane, Erik Schubert, Taryn Simon, Alec Soth, and many more.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Scheimpflug. Language. Silver.

Keep looking...

Roberto Boccaccino Uses Authentic Images of Southern Italy to Create Sci-Fi Atmospheres

Let Me Sowe Love — Roger Richardson’s Lyrical Street Portraits React to a Time of Anxiety

This Is JEST, the Space Where the Next #FotoRoomOPEN Winner Will Have Their Solo Show

Sophie Harris-Taylor’s Staged Portraits Celebrate the Beauty of Women with Skin Conditions

Under Construction — Alex Atack Captures Dubai’s Ever-Changing Urban Landscapes

FotoFirst — Mark Griffiths Got on the Road to Explore How Contemporary Wales Looks Like

We Are Ugly but We Have the Music — Marisa Chafetz Turns the Lens on Her Own Family