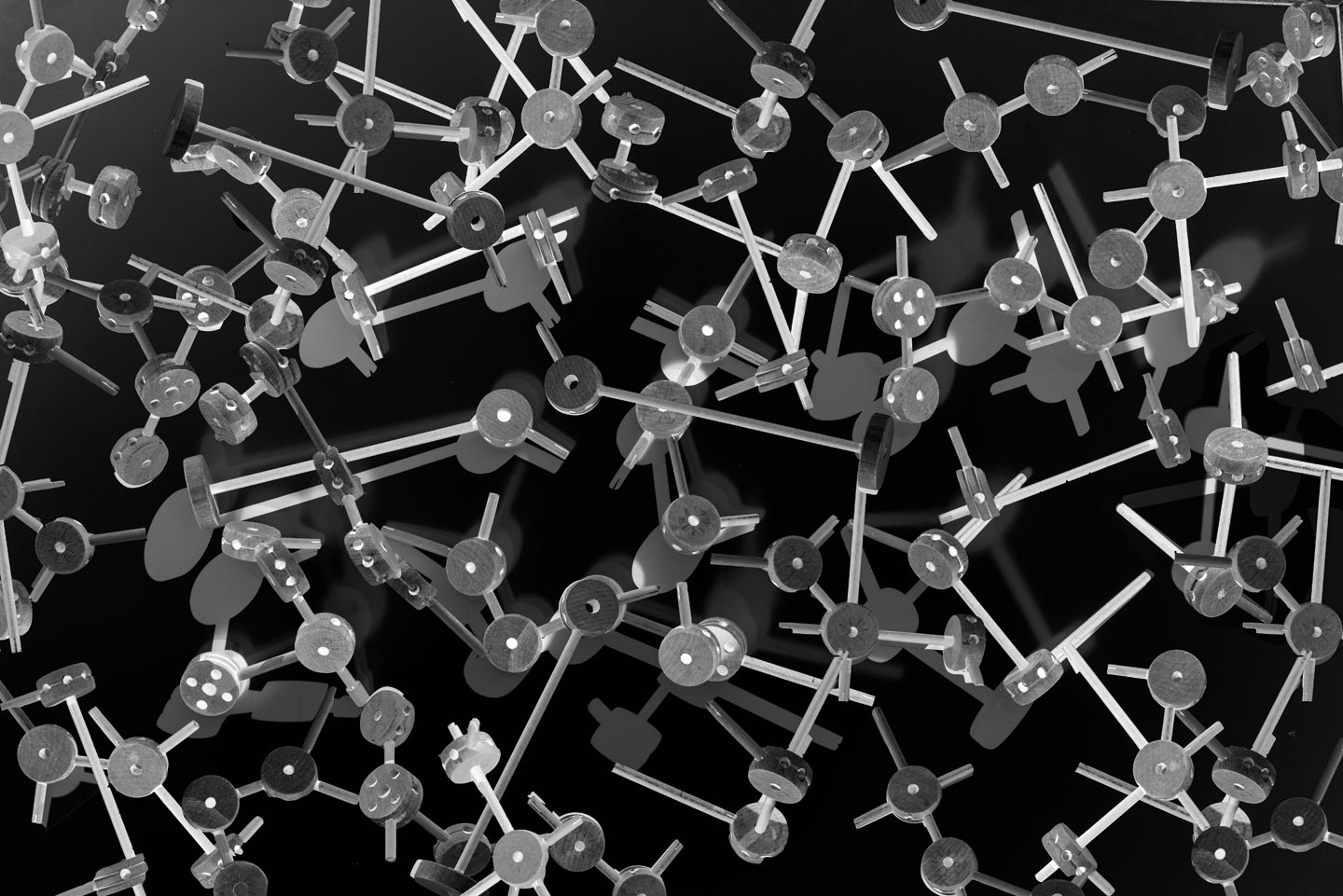

Selected Works: Nico Krijno

They say everyone is a photographer these days. We don’t agree. Everyone has a camera, sure; but being able to take a picture and being a photographer? Not the same thing in our book. Be it as it may, it’s true that the quantity of images taken and distributed in our day and age is unprecedented. The eccentric, experimental, sculptural work of 34 year-old South African artist Nico Krijno is a reaction to the overflow of all too similar pictures that we’re exposed to in modern societies.

For a good overview of Nico’s work in print, take a look at his recent monograph New Gestures published by L’Artiere.

Hello Nico, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Materiality, object-ness, flatness. staging, the sculptural, time, the medium of photography and its limitations.

You started your adventure with photography taking diaristic pictures firmly grounded in a documentary approach. When did you realize you could make images rather than take them?

It was a very natural and slow process of discovery. When I was about 10 or 12 I started trying to take very stark and minimal abstract photos in black and white. 1990s rural South Africa was pretty cut off from the rest of the world, so I had no exposure to art exhibitions or books. Both my parents were amateur photographers, but my experience of fine art photography was little to none. I was mainly exposed to record covers from my dad, and a few other sources at the library where my mother used to work, and of course films played a huge role. So later in my teenage years I grew bored of taking straight photographs and did other things, like film-making, theater, music, etc.

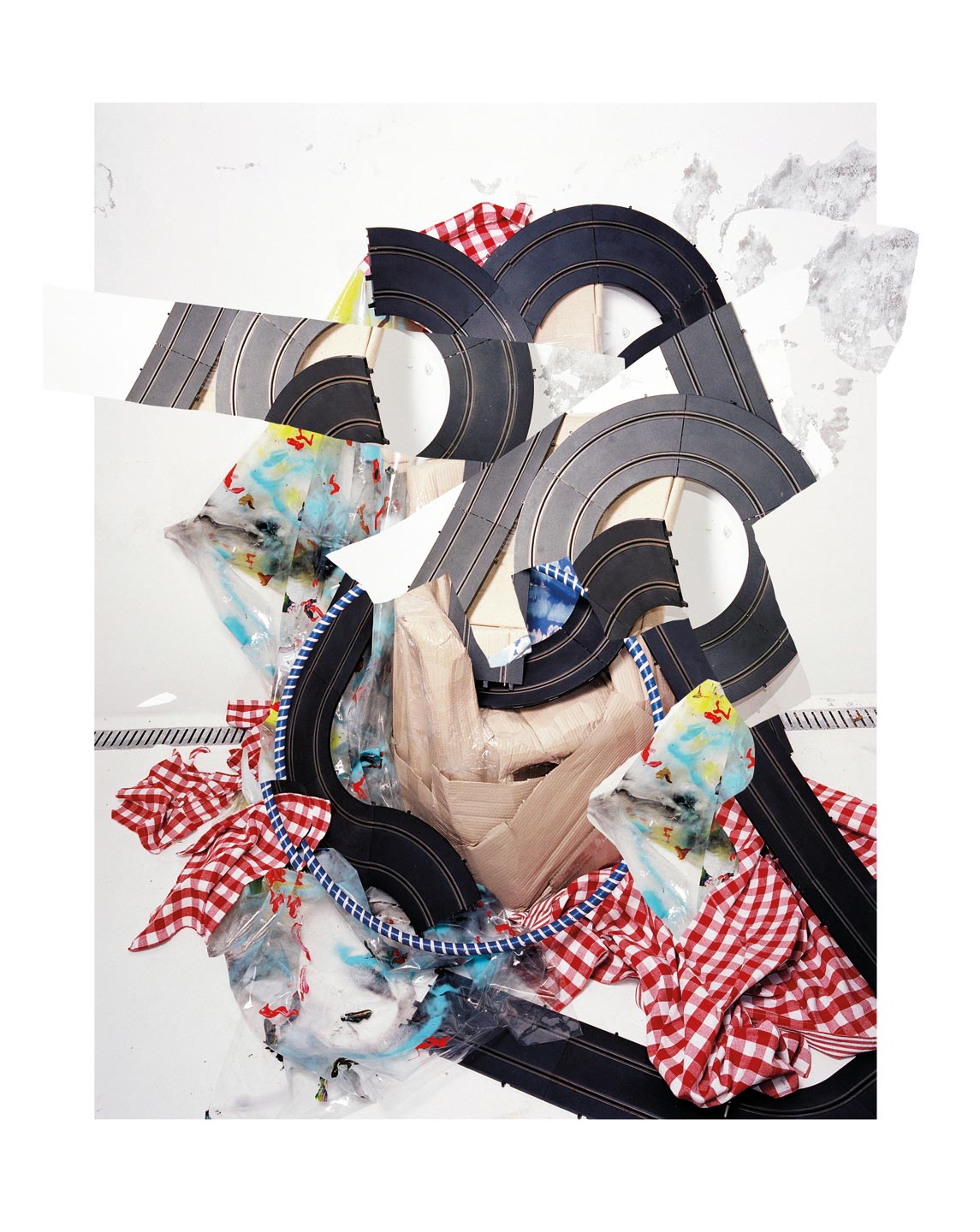

When I got back to photography in my early twenties… I knew i had something to say—I just didn’t know what exactly. I was trying so many things to discover what I was after, what worked for me. Then smartphones and the Internet changed everything; everyone started taking photographs, and I kept seeing the same images over and over again. My work is a direct reaction against that sea of homogeneity: I knew I couldn’t just take pictures anymore—I had to make the entire image, and use my previous experience in film-making and set design to create new, visually exciting worlds.

Your work is, as you yourself say, “pure research”. What are you searching for?

I would not say my work is pure research. Pure Research is the name of my blog, which I use as a sketchpad, a free-flowing narrative. It’s a way to keep track of my ideas and see what patterns emerge. I work on various concepts at once, constantly experimenting with different directions and techniques.

My work is not rooted in research or heady intellectualism, I’m just reacting to my immediate reality. There is a basic script that I follow, but I leave the whole process as open to chance as possible.

Can you describe your typical creative process? Is there a pattern or any guidelines you follow in your work, or is it entirely random?

Yes, there definitely are patterns—I’m very calculated and methodical. The usual starting point is me setting up a new space. Strangely enough, all of my previous bodies of work have coincided with me changing my work space. I’ve found that the environment, the cocoon in which I create is very important for me. I’ve never had that one studio, and there are periods where I just don’t have one and I’m simply working working outside in an abandoned lot, in a field, on a roof or wherever.

So I inhabit the space, get under its skin and see what it has to offer. I populate it and arrange it into a set—dress it like a teenager would decorate his bedroom. I source and collect props and materials, and select a few basic elements to play with, like potters clay, wood, bric-a-brac, etc. Then I start exploring these materials and objects in various ways, using paint, fabrics and more. It can get very messy—the mess is very important. This deliberate chaos results in a self-reflexive cacophonous drone/fingerprint of studio grime, which I then sample and use in the work. I think i can safely say that the toughest and darkest most hostile working environments have yielded the best results for me.

How do you know when your job on a particular image is done, and it’s time to stop working on it?

I guess I stop when the work clicks with the version I originally had in my head.

Seeing as how experimental your work is, what equals to a mistake for you? Does it ever happen that you abandon a new piece because you don’t feel it’s right?

I rarely abandon ideas. I live for beautiful mistakes, in fact I think there’s a lot of room for error in my practice. I don’t like things to be too perfect, forced and glossy. I want my work to be very spontaneous—just as the shutter clicks, all the cards might come tumbling down.

What are your main sources of inspiration?

Music is extremely important to me. I surround and wash my eyes in nature. My environment. Books. Isolation.

What have been the main influences on your photography, and what role does the South-African culture play on your work in particular, if it plays one??

I was mainly influence by the pain and struggles of daily life, the kindness of strangers, animals acting like humans. Anything my eyes have seen. To name a few photographers that I admire: Roe Etheridge, Lucas Blalock, John Divola and Robert Cumming.

As to South-African culture, it obviously plays a role but not a very direct one. My work is not overtly political or about place, and I find a lot of the work from superstars like Pieter Hugo and Roger Ballen very problematic, and sometimes predictable.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Thomas Albdorf, David Brandon Geeting, Peter Puklus… Marton Perlaki is doing great work at the moment. There are so many.

Keep looking...

Meet Anna-Maria Pfab, the founder of Kiosk Who Will Mentor the Next #FotoRoomOPEN Winner

Ayline Olukman Wins the Single Image Category of #FotoRoomOPEN | JEST Edition

Michele Palazzi Wins the Series Category of #FotoRoomOPEN | JEST Edition

Kovi Konowiecki Explores the Border as Both a Physical and an Emotional Barrier

Fashion Photography and Portraiture Blend in Simon’s ‘Masculinity’ Series

Moldova Elsewhere — Alfredo Covino Photographs Daily Life in a Declining Country

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Calls for Entries Closing in July 2018