Time to Rest — Line Søndergaard Photographs Norway’s Sleeping Truck Drivers

These days we’re featuring some of our favorite submissions we’ve received for the recently closed #FotoRoomOPEN | OSTKREUZ edition. We’ve seen so much good work that it will take a few weeks to share them all with you! (By the way, we’re now accepting submissions for the new #FotoRoomOPEN | Format edition—this time the winner gets a $1,000 award).

For road security purposes—namely to avoid accidents—truck drivers in Norway (as well as in other countries) must follow governmental regulations that force them to stop driving after an imposed amount of hours and get some sleep in designated resting spots. In all of Norway, however, such spots are 15 in total; so when the timer beeps and it’s time to rest, the drivers often just end up parking in a safe place and sleep on their trucks.

Time to Rest by 31 year-old Norwegian photographer Line Søndergaard documents the nights of Norway’s truck drivers: “When I was younger I used to live in Bergen, a city on the west coast of Norway. To get home and see my family I had to drive across the mountains. Everywhere on the side of the road, in the most remote places, I would see these giant trucks parked, their curtains down. I used to wonder why on earth they would park just there, in the middle of nowhere, so completely alone. As I started looking into it, I learned it was due to EU regulations that command that they stop at certain times. I figured that must be a lonely life, and got curious on what kind of person chooses this life for themselves. Speaking to people on what their idea of ‘truck drivers’ is, I found that most described them like you would describe a truck: big, aggressive, scary. I thought I wanted to find out for myself if that’s how truck drivers really are.”

As a photographer, Line is interested in social documentary, journalistic projects: “I want to show people something they should know. I want them to feel it and smell it. I want to tickle their curiosity. I believe that good photojournalism should touch us: if we are not emotionally touched, if we don’t feel empathy, we don’t engage; if we don’t engage, we don’t care. Good photojournalism should challenge the viewer—it should force us to see, to think, to review our pre-assumptions. Ideally, it stimulates a chain of thoughts that can encourage us to take a stand.”

To find the subjects of the work, Line simply got on the road and approached the truck drivers she would meet: “Drivers are always on the move, so making appointments isn’t really a possibility. Also, doing this by appointment would have felt more arranged, more set-up. So instead, I made research on the most trafficked routes in Norway, packed my bag, fueled my 1973 Volvo, and started driving. I chased moving trucks in landscapes by day; when the sun went down, I looked for the parked ones, knocked on the door and asked to spend the night. I stayed with each driver for that one night only, then the next morning we would separate our ways. Soon I found some key images that I started collecting: the trucks moving across Norway’s postcard-landscapes; the trucks parked in desert spots; and the portraits of the sleeping drivers.”

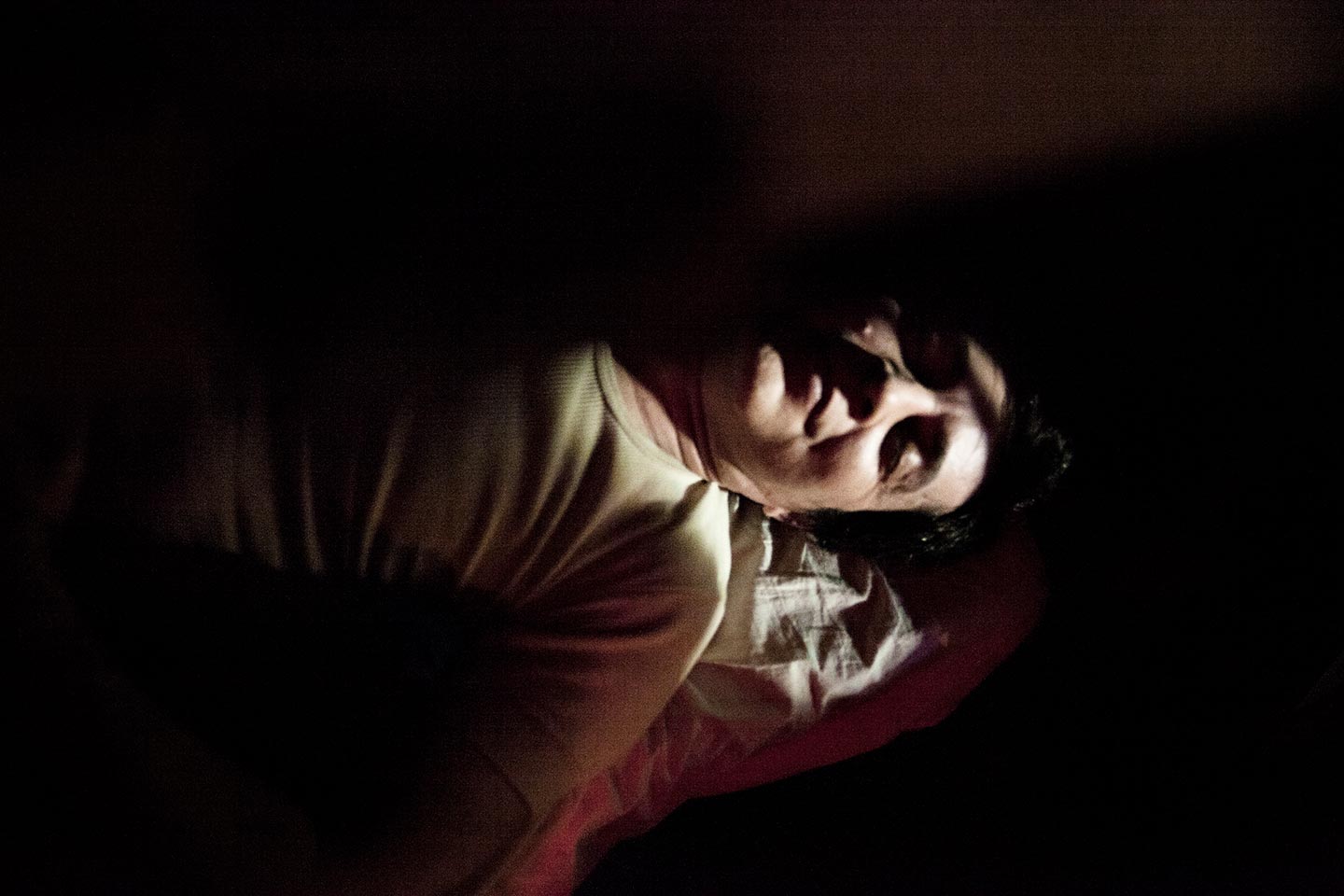

“My subjects were not like one figures a truck driver is. Some were, but I found most of them to be caring, reflective, interesting and interested human beings. I believe that the sleeping portraits invite us into this part of them. We can be naked in more ways than physically: when we sleep we are vulnerable, like a child, and this evokes empathy. I liked the idea of portraying the ‘big, bad guys’ in that way. I think I ended up sleeping with 35 drivers by the end of the project. I’m still in touch with most of them about where the portraits are being shown and such.”

“I feel it’s important to tell the story of these drivers from the point of view that I’ve chosen, as when truck drivers are in the press it’s typically bad news about accidents, aggressive driving, etc. In truth, most of the time, they work silently and smoothly in the shadows of our society. In Norway, we are completely reliant on them—our country’s extreme geography makes a lot of smaller places dependent on getting deliveries by road. Now the industry is in decline: fewer people become drivers, a lot of Norwegian companies are shutting down due to foreign companies pushing the prizes down, and those who still work face a more difficult and lonelier everyday as regulations become more and more strict.”

Time to Rest also exists as a transmedial publication. When Line started the project in 2014, one of her goals was to create work that could use different media and be presented in more ways other than just in print. “In 2014, this hadn’t been done much yet, but Snow Fall: The Avalanche at Tunnel Creek [a pioneering multimedia story published online by the New York Times in December 2012] had been recently released, so I looked at that publication a lot. I was then introduced to Tim Hetherington’s amazing series of sleeping soldiers, so this project ended up resembling it a lot.”

Time to Rest was also Line’s first long-term project, and taught her a lot about how to be a storyteller: “I got to practice how to be together with someone I don’t know. I feel being together is not always supposed to be comfortable and pleasant—it must create some tension, otherwise it’s boring. I also really felt in love with the night and spending it with strangers… It’s like something changes when you’re shut off from the world with a stranger. The conversation flows much more than it ever could during that 1pm lunch break, and to be lying there, in bunkbeds a meter apart, listening to the other falling asleep, creates this strange trust in someone you met just hours ago. In some way, this is the goal of this project: inviting the viewers into the trucks to join these moments.”

Some of Line’s favorite contemporary photography are Antoine D’Agata’s work for its unrest, Sally Mann’s for it sensibility and Eugene Richards’ for its social commitment. The last photobook she bought was Of fading memories by Erhan Can Akbulut (“A friend gave it to me recently, and I fell in love with it“).

Line’s #threewordsforphotography are:

Emotion. Empathy. Recognition.

Keep looking...

FotoFirst — Do You Sometimes Dream of America? Mario Wezel Shares His View on the U.S.

Industrial Sites and Residential Areas Blend in Sergio Chiaramonte’s ‘Heavy Land’

Neta Dror Portrayed These Girls When They Were 15 Years Old, and Then Again at 20

Michele Borzoni Photographs Thousands of Italians Applying for a Job in the Public Administration

Jordi Ruiz Cirera Exposes the Effects of the Global Food Chain on South America’s Communities

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2017

Andrey Lomakin Portrays the Ukrainians Who Are Buying Weapons for Self-Defense