Inside the Bunker-Turned-Theater Where Visitors Relive the Atrocities of the Soviet Era

The Lithuanian Project is the name of a group of photographic works about Lithuania curated by the MAP6 collective. 52 year-old British photographer Barry Falk contributes to the project with System of Absurdity, a series of pictures of an abandoned bunker used as a communications center during the Soviet Era. Today, the bunker has been transformed into a stage where visitors are invited to participate in a re-enactment of the Soviet regime.

Hello Barry, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Photographing places and spaces which are easily overlooked but hold a certain disturbed quality. These may be incidental urban spaces, such as loading bays at the backs of shops or stairwells in hospitals, or peripheral landscapes that hold a sense of abandonment. My focus is upon revealing certain states of mind which are buried in both the urban and rural landscape. I am particularly interested in the edges of the city where the built-up areas merge with the rural landscape and the friction that can occur at these points.

More recently I have become very interested in photographing areas that have undergone a process of displacement and trauma: locations further afield, particularly Poland and the Baltic countries, to explore how these places hold a sense of memory and collective loss.

Please tell us what is the Soviet Bunker that we see in the pictures of your project System of Absurdity, and what can be found in it.

The Soviet Bunker was originally a telecommunications centre, set up by the Soviet Union as a back-up station to keep broadcasting in the eventuality of a nuclear war. It was built between 1983 to 1985 and abandoned in 1991 when the Russians left Lithuania. It covers an are of 2,500 m2 and lies beneath a mound of earth three meters deep. You enter the extensive bunker via huge blast doors. The space has now been adapted into a place of theatre where an actor, dressed as a KGB Officer, re-enacts, in exaggerated manner, what it would have been like under Soviet Rule. Some of the the rooms, which open off of the long corridors, are set up to present different scenes, each one presenting an aspect of life under the Soviet Union, from the interrogation room to the classroom, the room with Lenin propaganda to the Soviet apartment.

Who maintains the Soviet Bunker, and why?

The Soviet Bunker is maintained by Mindaugas. He told me that he originally had the idea to transform the old telecommunications bunker into a place of theatre from his aunt. His aim is to create a space where the trauma of the past can be remembered through a process of re-experience. It is not intended as a place of fun but as a place of education and remembering. To acquire the use of the empty bunker he needed to request permission from the Lithuanian government and then adapted the space so that he could hold performances within it. The Bunkeiro Komando, as he refers to it, would have been left stripped bare and the power and air conditioning system shut down. Mindaugas now maintains the bunker by hosting frequent performances: re-enactments of the ‘reconstructed Soviet Union.’

Why did you decide to make a project about the Soviet Bunker?

Prior to going to Lithuania I had concentrated on urban and semi-rural landscapes, projects with titles like Incidental Spaces, Peripheral Landscapes, Deconstructing Car Parks, all of which could simply be transferred to Lithuania, however were not specific enough in terms of what Lithuania meant, who Lithuanians were and what the country had experienced in its recent history. I needed to broaden my range, and the obvious connection for me was the Jewish narrative. As I looked into the post war history though, I realized that there were two dominant political forces that had shaped and misshaped the country: the German occupations, in particular the atrocities of Nazi Germany, and the long Soviet Occupation. One centered around the Jewish narrative, and for this I identified a number of massacre sites and memorial sites. But I was also very interested in exploring the impact of the Soviet Occupation on the Baltic States between 1944 and 1991 and how this is remembered today. Bearing in mind we only had six days to complete our projects I arranged my days to visit a number of locations in and around Vilnius: as well as the Ponary Massacre Site and the Jewish Synagogue and Cemetery, I had also been told about a place called the Soviet Bunker which appeared to offer an ideal location to explore the legacy left by the soviets.

Did you take the tour of the bunker guided by the actor who plays a Soviet officer? Can you describe what the ‘show’ is like?

I was very lucky to be allowed to both watch the tour but also to wander freely within the bunker as ‘guest photographer.’ The performance is a one-man tour-de-force: Mindaugas employs an actor to perform the part of the KGB Officer. He also dresses up in soldier uniform but his role is minimal, accompanying the performance but taking no active role.

On the day that I visited the actor being employed was Mindaugas’ favorite one: a large guy who was a trained opera singer. The performance was for three hours and commenced upstairs in the visitors center, where the visiting students from a local college were dressed up in heavy grey coats, then marched through various drills on the courtyard before descending into the bunker. Mindaugas is very specific about the route that the visitors take, entering a back entrance and then descending to the bright red Lenin room, where they are subjected to further lectures from the KGB Officer. The party is then led through the bunker, via the interrogation room, where they can re-enact interrogations, and to the gas masks room where they can put on the gas masks. In the basement Mindaugas has set up an area where he has the visitors re-enact an absurd exercise of moving objects from one area to another—this, he explained to me, represents the absurdity of the Soviet System. The performance ends with the actor asking the audience whether they like their freedom, the implicit message being to remember the past so as not to repeat it. Finally, a meal is had in the banqueting hall upstairs.

How would you define the atmosphere surrounding the Soviet Bunker, and what impressed you more strongly about the place?

Imagine an extensive bunker set six meters underground, entered via heavy blast doors, with corridors running off at right angles and multiple, identical doors; imagine an underground maze made from un-rendered concrete and then open a door and be faced with a puzzling array of set designs, like sets from low-cost Doctor Who episodes: the red room with gleaming white bust of Lenin, table laid out with photographs of the Central Committee, and maps of the world on the wall where there are no separate Baltic States—just one grey blue mass of the Soviet Union; the room with gas masks laid out on display on trestle tables; the interrogation room and the medical room with gynaecological chair and forceps. It is a foreboding yet deeply fascinating space, semi-derelict yet clearly functional in an absurdist manner. It was like an art-piece carefully arranged by an obsessive artist re-playing tortured memories. What impressed me most was the care taken in by Mindaugas in both salvaging and collecting together all of the objects and Soviet paraphernalia from local markets and meticulously arranging each space with the dedicated affection of an artist.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on System of Absurdity?

For this project I had no set idea of how I would photograph the space and the performance; I went very much with an open mind. Upon entering the space, though, it was immediately obvious to me as to how to go about documenting it—drawing in past experience of photographing interiors of large derelict structures in the past. My references were both general, from numerous other photographers, and specific to my own practice in terms of framing, composing, focusing on detail as well as wider scenes to build up a comprehensive sequence of images.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Prior to focusing purely upon photography I was a painter print-maker and have been heavily influenced by painters like Anselm Kiefer, Luc Tuymans and Peter Doig. Within the photographic world there are numerous influences and likes, including, amongst many, Edgar Martins, Thomas Struth, Alec Soth, Mark Powers, Andreas Ghurke and Guido Guidi.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

I am very interested in the work of Ori Gersht and the experimental nature of his projects such as The Clearing and Liquidation. The work of Tamas Dezso, Notes for an Epilogue, and Danila Tkachenko, Restricted Areas, are also inspiring.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Trauma. Memory. Peripheral.

Keep looking...

FotoFirst — Olga Sokal Photographs Lynch, a Small U.S. Town Suffering from the Decline of Coal

Adagio — Laura Ghezzi’s Poetic Images Respond to a Time of Change in Her Life

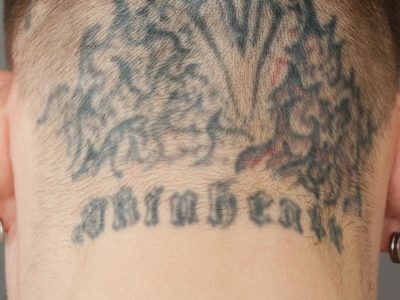

Jakob Ganslmeier Portrays Former Neo-Nazis Who Are Removing Their Nazi-Inspired Tattoos

FotoFirst — Michael Swann’s Series Noema Is Inspired by (Alleged) Apparitions of the Virgin Mary

In His Series Cicha Woda, Piotr Pietrus Collects Mundane Observations of Reality

Mirjana Vrbaski Shares Her Minimalist Portraits of Women from Her Series Verses of Emptiness

Giulio Di Sturco Captures the Alarming Conditions of the Ganges River in Stunning Photographs