Tatiana Bondareva Photographs the Young Prisoners of a Saint Petersburg Correctional Institution

We’re featuring this project as one of the best series submitted to the recently closed #FotoRoomOPEN | Gnomic Book edition. (Did you know? We’re now accepting submissions for a new #FotoRoomOPEN call—the winner wins a solo show at Fotogalleri Vasli Souza. Find out more and enter your work).

Boys by 35 year-old Russian photographer Tatiana Bondareva captures the daily life of the young prisoners aged 14-18 detained in a Saint Petersburg correctional institution. Tatiana first visited the facility more than 15 years ago as part of a group of church volunteers organizing a football competition between prisoners. On that occasion, the other volunteers and she spent a whole day with the prisoners playing in the woods: “We ran among the trees, cooked food on a fire, and talked friendly with kids guilty of robberies, rapes and murders. We joked about whether any one of them was going to escape through the woods, but none of them did. I remember that one of those boys, who looked very good-tempered, confessed to me in the evening that he had killed a person, and asked what I thought about it.”

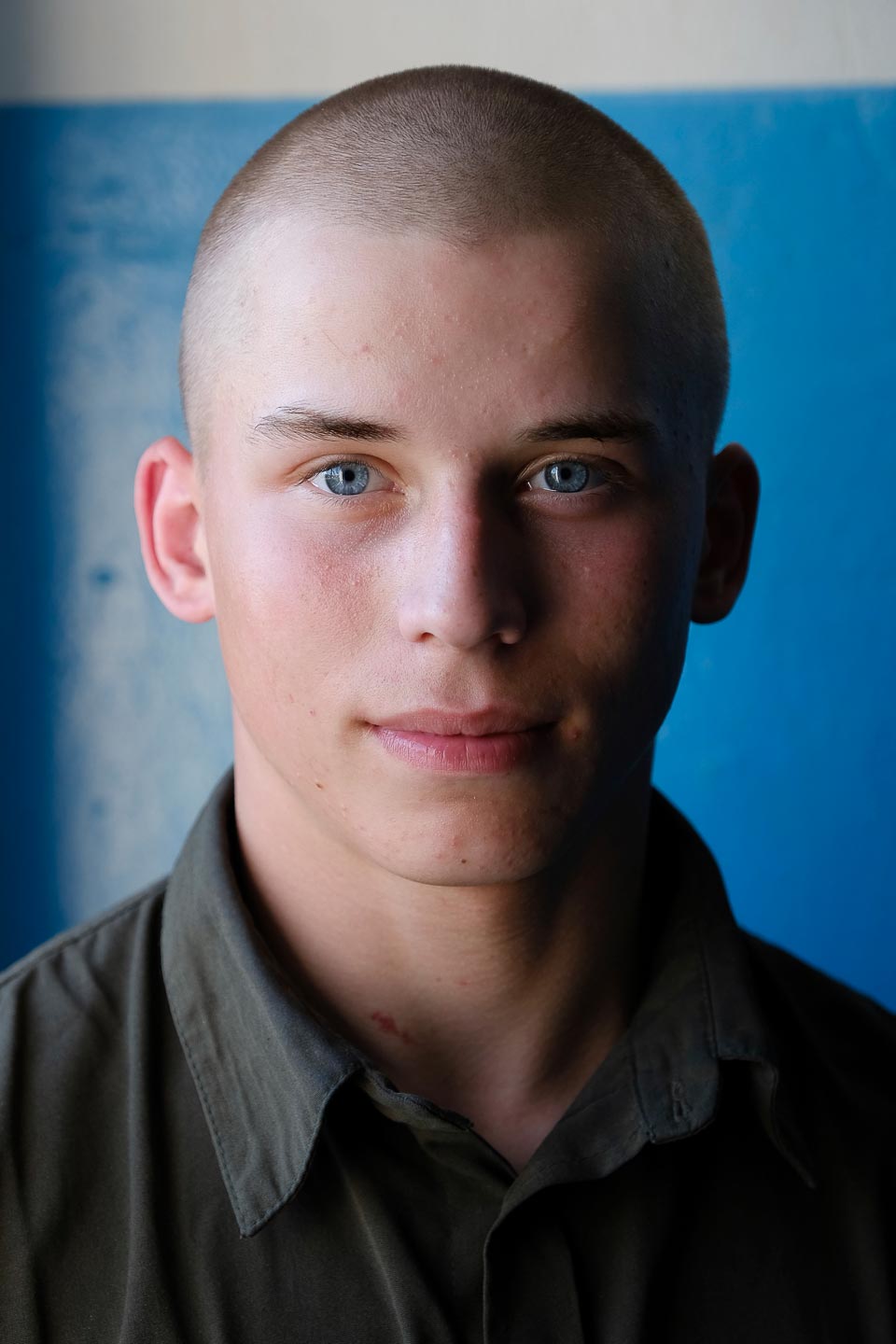

When Tatiana visited the institution years later, things went very differently: “This time I was a stranger, and twice as old as the boys. They clearly ignored me and turned their faces away. At first, they were very unfriendly, and I didn’t want to photograph them against their will. I tried very much to be invisible, but I was a new person in their closed society: I was always under control. They made the effort of not showing their emotions, and were permanently on the lookout. While photographing, I tried to wait for rare moments when they would forget about me and let their guard down. I wanted to see the person they were afraid to show, to capture the times when they would behave not like prisoners, but just like teenagers.”

During her visits to the prison, Tatiana was always accompanied by an officer, so she admits that her images “only show what the facility administrators were willing to show me—I may have just created a perfectly sanitized representation of a Russian penal colony.” In the institution, the boys all wear a similar uniform and no one can go anywhere alone—they can only move in groups (“Visually, it looks like a troop of cloned robots“). They go to school and work in a manufacturing facility; in their spare time, they can attend recreational classes such as a shadow show, a cartoon studio, and an art studio. “They even have their own YouTube channel where they post their music videos,” Tatiana says. “Every three months, their parents can visit and spend four hours with them, although not everyone’s parents participates. On these days, the boys perform in a concert and make dinner. I was surprised to see how excitingly they were learning verses by heart prior to parents’ day, and how they showed them stuffed toys they made or the harvest they yielded. It seemed to me that they were compensating for their childhood. That’s why I called the series Boys.”

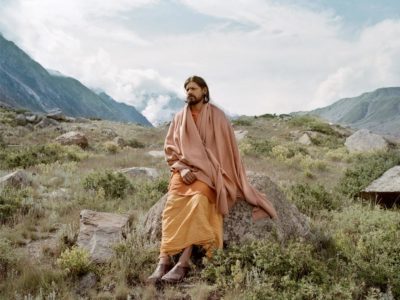

Shockingly, Tatiana reveals that many of the prisoners wanted to be detained: “Becoming a prisoner is considered prestigious in the criminal circles they belonged to outside. Once in the institution however, they were surprised to find out that life as a prisoner was different and less harsh than they expected. In fact, they try to act as if they were in a “real” prison. Every juvenile colony has its own hierarchy. I shot a picture of a guy wearing a tracksuit, sitting in an armchair under an image of Jesus Christ: he is the leader of the institution I visited. The other prisoners began to interact with me only after I talked to him.”

Tamara remarks that while some of the prisoners may actually be dangerous (“Talking with them really creeps you out: you don’t want to encounter them in a dark alley“), others were detained due to stupid things they made, and hopes that her images raise awareness on the lack of correctional facilities in Russia such as the one she worked in. “I see this place not simply as a custody facility, but also as a new home where prisoners adapt to obeying to a set of rules and do activities they didn’t before, like regularly attending school, going to church, etc. There should be more such places in Russia. Not only does the country’s existing juvenile justice system not correct, but it also corrupts the prisoners aged under 18. I’m not saying that it should be eliminated or that criminals should not be imprisoned, but the whole system should be reformed to really make an impact on the prisoners before they are released, otherwise they will go back to committing crimes and will keep being a threat to society.”

As a photographer, Tatiana is interested in “closed societies where people behave differently than normal. Social isolation, both forced and voluntary (including slavery or imprisonment), affect a person’s behavior and lifestyle. It is interesting to me to seek and identify the borders that limit someone’s freedom, or that of a group of people. I use the camera to visually capture how an individual’s behavior changes due to restrictions imposed by someone else.”

Tatiana’s #threewordsforphotography are:

Hope. Home. Freedom.

Keep looking...

Infinite Perimeter — Michalis Poulas Translates Greece’s Times of Crisis into Downbeat Photos

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2017

FotoFirst — Daniel Zhang Discovers China Following the Ancient Route of the Porcelain Trade

Welcome to the UK’s Smallest City

Once a Dream Did Weave a Shade — Karlis Bergs Investigates Why We Enjoy Being Specators

Hold Your Breath — Arden Surdam Creates Mythical Figures Wrapping Her Models’ Heads with Fabrics

Milky Way — Vincent Ferrané Captures the Joys (and Pains) of His Wife’s Breastfeeding