FotoFirst — Landon Speers Creates Original Music to Accompany His ‘Portraits of Nature’

Premiere your new work on FotoRoom! Show us your unpublished project and get featured in FotoFirst.

Wild Rose by 30 year-old Canadian photographer Landon Speers is a book of photos of natural scenes for which Landon also created a set of instrumental songs—in one word, a soundtrack—to accompany the images. You can buy your copy of the book here, and listen to the music through the player below:

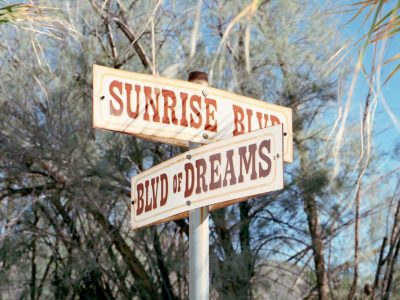

“The pictures that comprise the book are mostly from California, Vancouver, Alberta & New York,” Landon says. “The initial edit was larger and included more locales, but in piecing the project together, it whittled out some of the other places that didn’t quite fit in the end. I’d been caught up with taking a lot of portraits for some time and noticed I was responding more to trips I’d take outside of the city when I got the chance. I hadn’t been back home for a visit during autumn in years and when I did, it made some things click in regards to the nature I grew up around and feelings that used to be more familiar. I was missing the calm experienced during those excursions, and thoughts on a more deliberate approach to photographing them again began to form. The idea was to put myself in a headspace wandering through environments with an openness to my surroundings, waiting for elements of it to catch my eye. It formed into a meditative approach to seeing things in nature that struck me in a similar way that people would. That led to perceiving the images more as portraits of nature than landscapes.”

Before working on Wild Rose, Landon had never mixed up his practices as a photographer and a music creator: “I’d always identified that making music was a meditative and cathartic thing, so when I developed this new approach to taking photos that I’ve just described it seemed natural to pair it with a similar headspace as making music. They both informed one another throughout the process as it often meant that I’d write or record music during the same trips the images were taken. In California for example, I was house sitting a friend’s place for some days and I would return from desert treks and record myself playing the piano with no expectations other than to keep some of the feelings of that day going. Mornings might find me going over what I’d made the night before, while preparing to venture out again. In the end it set a feedback loop with each side pleasantly informing and affirming the other.”

Landon wanted the relationship between images and music to be “gentle and suggestive, instead of direct and commanding. I’m often drawn towards art that is more subtle or nuanced with aspects that leave room for your mind to wander or imagination to be spurred. Maybe it’s a personality thing, but I try to impart a similar approach to much of my work as well. As a kid I really latched onto scores and soundtracks, and the ability for audio to influence visuals has always been of great value to me. Sounds engaging another sense can amplify sights or at times, even conjure ones that aren’t even there. In an attempt to make two different mediums from one place, I wanted to leave room for others to feel stuff out, have their own response or reflections rather than direct them to one narrative. I guess inherently, since I made a physical book and not a music record, the photobook has a bit more prominence as ephemera, but ideally I’d love for both to stand on their own and complement one another.”

There are many similarities between music and photography, according to Landon: “I think both can resonate with a lot of human response and emotion in similar fashion. Moods can be set, and things like tension, peace, texture & contrasts can be explored. Feelings of presence, nostalgia or memory can also be elicited by both—just using different inputs. Obviously there are differences too, but those are largely more in logistics than emotive qualities. For example, how they’re consumed is different: 20,000 people aren’t going to Madison Square Garden in one night to see photography, and there are no Top 40 stations cycling through the hottest images today.”

“Ultimately I hope viewers’ response to Wild Rose is one that allows brief respite or a gentle escape—a pause and reminder that these spaces aren’t always just out in the middle of nowhere, but down the street in your neighbor’s garden, or that tree you pass on the corner during your commute to work. I intentionally paced the book to invite you into a world mostly void of humans and end with a return to humanity. There’s some nods and smaller glimpses of us throughout the book, but that absence is part of what made the images feel more akin to portraits than landscape vistas and offer a focused connection. I hope viewers are left with that mental breath of fresh air, only to return feeling encouraged to be more aware of their surroundings, and thus more present within them.”

Landon’s main inspirations for the Wild Rose photographs came from painting, in particular Flemish and Dutch artists like Isaac Van Ostade, Jacob van Ruisdael and Gillis van Coninxloo: “I’m really drawn to the ability of artists of that era in imbuing their pastoral landscapes with such mood. It often seems to lean more towards imparting the feeling of being there versus a facsimile of their views: I found myself drawn to tinted shadows conveying golden hours or sunrises, and patches of sunlit-drenched foliage that gave a sense of feeling that warmth instead of just seeing it.” As to the music, he found inspiration in the work of contemporary music artists like Tim Hecker, Ben Frost, Christina Vantzou, Jon Hopkins and Nils Frahm.

The thing about photography that Landon has always enjoyed the most is “its ability to expose me to others’ experiences and locations different than my own. I can’t think of many career paths where you get to jump into places so quickly and engage with such permission. On an aesthetic level, I’ve always been drawn to photography that seems timeless—work that could have been shot last month, year, decade or a generation ago but still carries some sense of reliability, or urgency.” The main influence on his artistic practice were his parents: “They raised me in a fairly strict and conservative religious home, but also were wonderfully supportive in fostering imagination and creativity. They were also big supporters of being outside a lot. Upon leaving the religious upbringing, I then possessed curiosity matched with new found freedom to explore things in a way that edified that. Punk music also was a wonderful accelerator to pushing me outside my comfort zone and meeting people who shared new ideas, thoughts, feelings & acceptance that resonated. Music has played an enormous role in my photography, but I also credit things like painting, drawing and sculpture as well.” Some of Landon’s favorite contemporary photographers are Ian Bates, Tonje Thilsen, Lola & Pani, Valerie Chiang, Noah Kalina and Whitten Sabbatini.

Landon’s #threewordsforphotography are:

Many. Different. Directions.

Keep looking...

These Apparently Ordinary Places Hide a Horrible, Horrible Past

Between Media Representation and Reality: the Identity Crisis of the American West

Inside the Hotel Polana, a Decaying Resort That Used to Be a Base of the Communist Party

FotoFirst — Two Photographers Observe the Radical Changes of China’s Landscapes

Stranger Fruit — Jon Henry Reinterprets the ‘Pietà’ to Denounce Police Violence Against Black Men

House of Surprises — Kathryn Allen-Hurni’s Portraits from the Twins Days Festival

Edging, GA — Anna Brody Creates a Fictional Town That Only Exists at Sunrise and Sunset