Resistance, Nature and Mysticism: Welcome to the Remote and Fascinating Region of Dersim

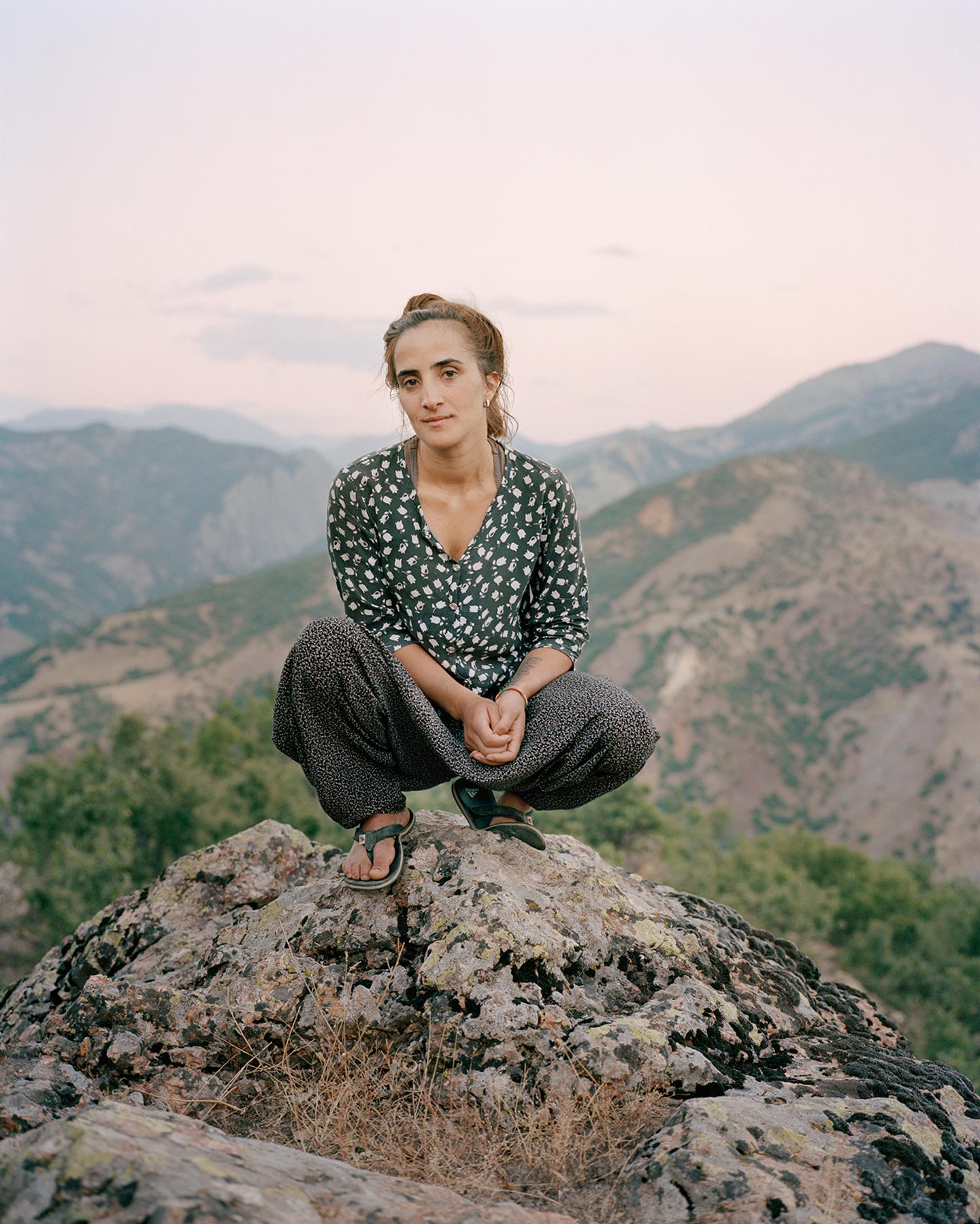

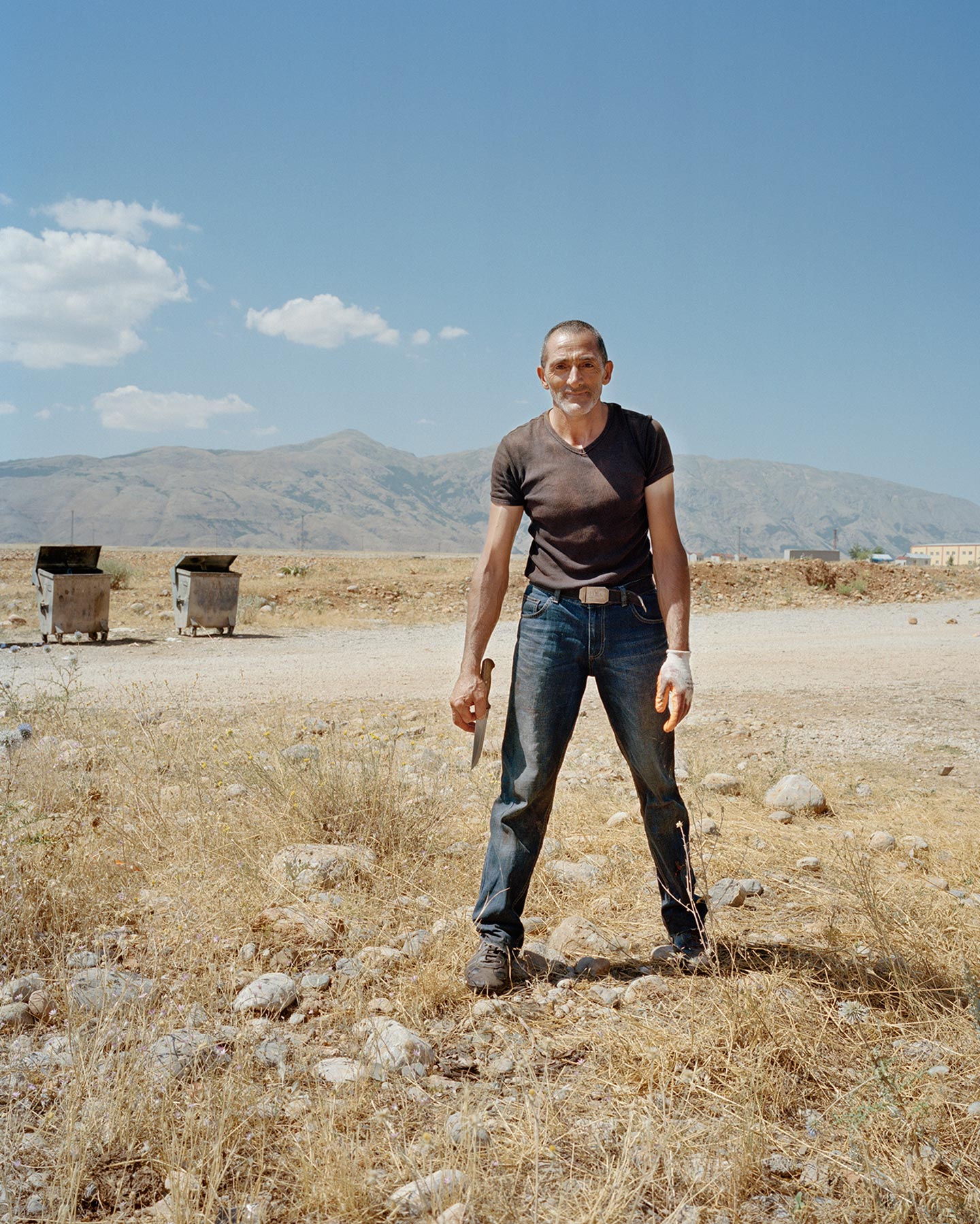

Initially, we reached out to Miriam Stanke about featuring her subjective reportage And the Mountain Said to Munzur: You, River of My Tears after seeing the images alone. Her photographs of Dersim, a region in Eastern Turkey, were beautiful enough. Speaking with Miriam, we also discovered the tragic yet fascinating story of this remote area, a cradle of religious minorities with a predominance of the mystic-inclined Alevism and a history of bloody resistance against the Turkish government.

Hello Miriam, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

As a documentary photographer I am interested in raising awareness for certain issues and telling stories with my pictures; but an immense part of my work is about discovering and understanding, not only for the viewer but also for me as a photographer. Photography can help give people a better sense of certain places, situations, conflicts, etc. In a sense, it is probably about trying to understand and giving sense to the complexity of the world.

Please tell us a bit about the tragic history of Dersim and its relationship with Turkey.

Dersim’s history is characterized by its religious diversity. It is nowadays a relict of the disappearing mosaic of religious traditions within the region. In the 1930s the Turkish military destroyed the local tribe systems, a process that climaxed in the genocide of 1937-38. Before this tragedy happened, no authority was ever able to control Dersim, not only due to the area’s mountainous landscape—full of canyons and caves—but also because the local population was widely isolated from other societies until the 20th century. Oppression and persecution of religious minorities during the Ottoman State made this region a last refuge for groups like the Alevis and the Armenian Christians.

Dersim also became an important part of the Leftist political movement since the 1970s. It is therefore even more a symbol for resistance and local identity. Nowadays the political struggle is so entangled within the religious and cultural notions that it is hard to keep the different aspects separate.

Dersim is the only region in Turkey where the majority of the population believes in Alevism. What are the main principles and beliefs of the Alevi religion?

Alevism is a very heterodox variation of Shi’i Islam which draws many influences from other beliefs like Shamanism, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism—this is most likely due to wandering Sufis who came to this area. The Alevis are quite open and welcoming: the whole culture is based on sharing and community. People are extremely hospitable and you will spend your days getting invited to have tea and food with them.

One of the main differences between Alevism and traditional Islam is that there is no separation between men and women. Women have an especially strong position in Alevi culture. For a Westerner coming to Dersim this may not seem apparent at first sight since women are often in charge of keeping the house and raising the children; but there actually is a genuine idea that men and women are equal, as is noticeable in public spaces and occasions. For example, women are not separated from men during holy gatherings.

The Alevis pray not in mosques but in ‘cemevis’, or ‘houses of gathering’. The Turkish State keeps building mosques in the area to assimilate people’s beliefs, but the cemevis are used much more. Here, men and women gather to sing, pray and practice mystic rituals. Nature is very important in Alevism, and especially the sun and the moon. Instead of taking pilgrimages to Mekka, the Alevis find their holy places within the nature that surrounds them: they have legends about certain rocks, trees and other local places nearby them which are often only familiar to the people from the neighboring villages.

What brought you to the region of Dersim in Eastern Anatolia, and for how long have you worked there?

I got to know about Dersim through an anthropologist friend. He was interested in religious minorities in Kurdistan and had been working in this area for a couple of years. I actually approached him first regarding another project when he told me about his current studies. I decided to join him and stayed for about three months.

What’s the meaning of the project’s full title, And the Mountain Said to Munzur: You, River of My Tears?

The title is taken from a poem and is freely translated to English. For me it implies all the aspects of Dersim. As I mentioned, Alevism has a strong connection to nature, and many natural spots throughout the region are regarded as holy. One of these is the Munzur river and its springs. The presence of the Munzur river and the mountains made the conquest of Dersim always difficult; in a way, they protected the local population. Personalizing them is the Alevis’ way to worship them and acknowledge their importance.

How did you approach the series? Was there anything in particular you wanted to capture in your photographs?

There is something mystical about Dersim’s history and landscapes, so I wanted to use the power of symbolism within my pictures. I normally don’t shoot a straight storyline; instead, I prefer to give an impression of a place by combining landscapes, portraits, still lifes and action shots that evoke the feeling and energy of the place. I want to enable people to enter into another world by using pictures that go beyond the things you can see.

Of great significance to me were all the signs scattered within the landscape. There are political and religious symbols everywhere: graffitis on the walls, a flag of Mao in the mountainside, effigies of the imprisoned PKK founder Öcalan, altars with candles dripping wax along the roads, etc. I found this really important to take into account while shooting. The theme of the river pops up repeatedly, as well as the symbolic color of red representing suffering and blood on one hand, but also strength, resistance and a fighting spirit on the other.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on And the Mountain Said to Munzur: You, River of My Tears?

I looked a lot at Carolyn Drake’s series Two Rivers, which I found fascinating because of its simplicity. The pictures bear a lot of mysticism and let you go beyond the pure image. Paul Graham’s Troubled Land was also a source of inspiration. He managed to have these little seemingly unimportant references within his pictures, which at the end make the story. It is often the details you have to look for, the not-so-obvious bits which means you sometimes also just have to take your time to let things settle. I like that as I am always trying to avoid stereotypical pictures.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

It’s difficult to tell. I guess as you are always surrounded by visual keys, it is a constant flux. In earlier years I looked a lot at photographers like Joakim Eskildsen—I love his Roma Journeys work. I guess during my time at the London College of Communication where I studied I was also influenced a lot by other photographers working with me, because you are in a constant exchange. It probably made my photography a bit cleaner. Edmund Clark was one of my tutors and influenced my work forcing me to be clearer in what I want to tell with my pictures. Other photographers whose work resonates with me include Alec Soth, Bryan Shutmaat, and Rob Hornstra.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Discover. Understand. Connect.

Keep looking...

Adagio — Laura Ghezzi’s Poetic Images Respond to a Time of Change in Her Life

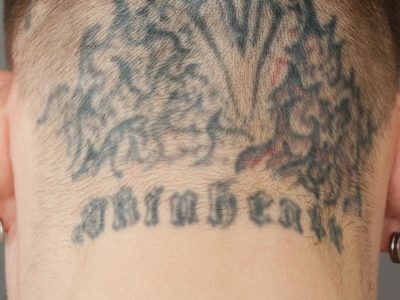

Jakob Ganslmeier Portrays Former Neo-Nazis Who Are Removing Their Nazi-Inspired Tattoos

FotoFirst — Michael Swann’s Series Noema Is Inspired by (Alleged) Apparitions of the Virgin Mary

In His Series Cicha Woda, Piotr Pietrus Collects Mundane Observations of Reality

Mirjana Vrbaski Shares Her Minimalist Portraits of Women from Her Series Verses of Emptiness

Giulio Di Sturco Captures the Alarming Conditions of the Ganges River in Stunning Photographs

Alvaro Deprit Creates Magical Images of Andalusia, His Family’s Original Homeland