FotoFirst — Welcome to Mandela, the Square in Madrid That Looks Like a Prison

27 year-old Spanish photographer Carol Caicedo presents Mandela, a work of conceptual photography that takes a look at a particularly drab square in Madrid, the Nelson Mandela square, to reflect on themes of power and oppression, both physical and psychological.

Hello Carol, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I’m interested in photography as a language capable of creating meaning. I enjoy the possibility of making a statement through a series of images, of using photography as a tool to develop an idea from a personal point of view. I’m especially attracted to everyday life when it seems to speak of the order of things and thus invites me to reflect on the world we live in. I’m also interested in investigating how the external and material reality affects our inner selves; how the social sphere shapes the individual’s soul and conscience.

What is your Mandela series about, in particular?

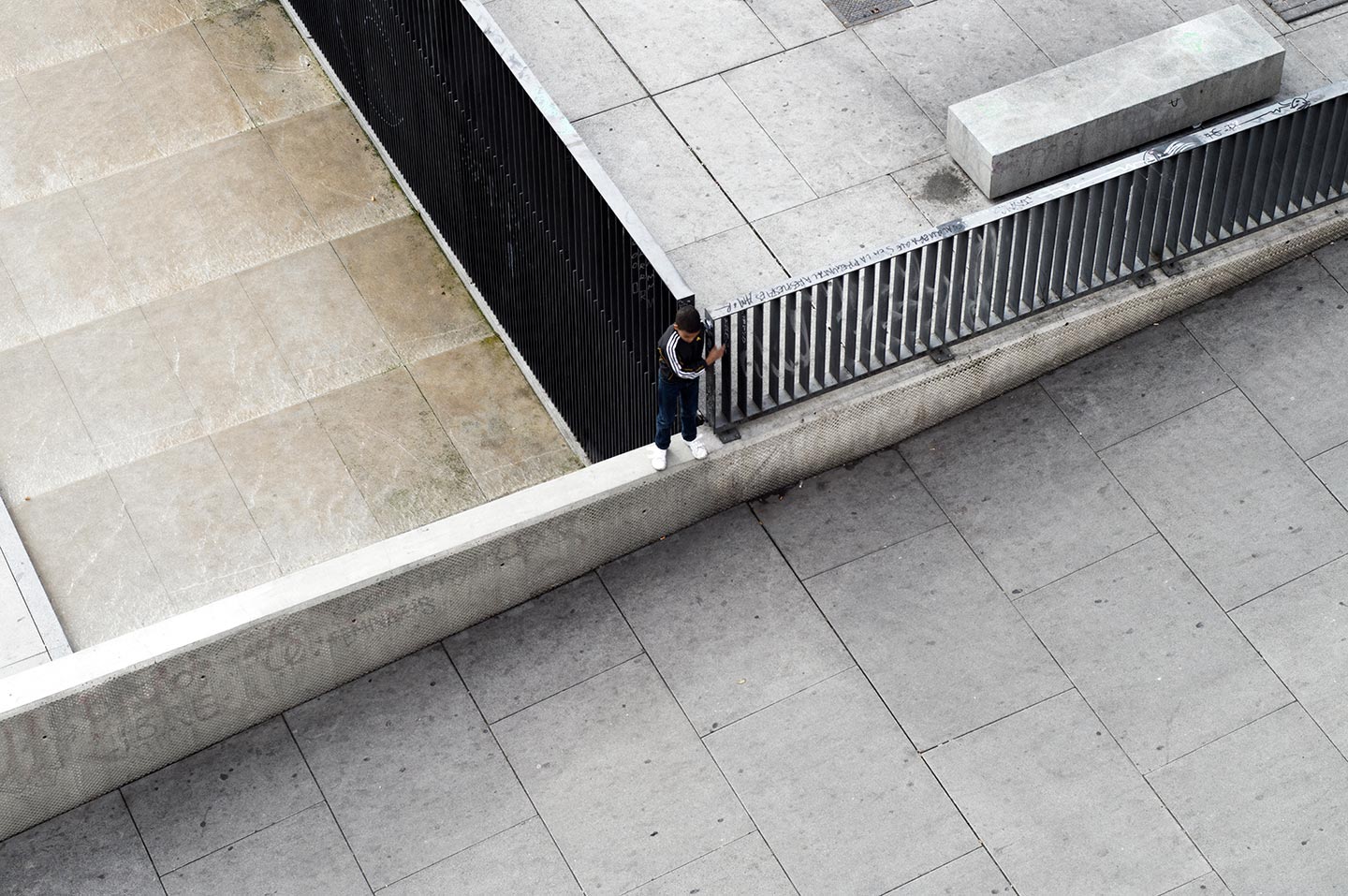

In my neighborhood in Madrid, Lavapiés, there’s a square that looks like the courtyard of a prison. The latest renovations have transformed the square in a cold environment; even the benches, which are made of cement rather than wood and have no backing, provide no warmth or comfort.

The Mandela project grapples with two opposing concepts: social control and human sensitivity. The whole series is hinged on this dichotomy. It’s a reflection on ideas of power and submission on one hand, and strength and vulnerability on the other. It’s a psychological portrait of our society and urban architecture that goes way beyond the physical qualities of the space: there’s no need to use bricks to build a prison.

Why did you decide to make a project about Mandela square, and how would you describe it?

Initially my goal was to make a project about the entire neighborhood of Lavapiés; but to escape cliches I needed to define a more precise scope for the work. Then I realized that Nelson Mandela square had something peculiar about it, and I decided to focus on it. By looking at a small corner of the world, circumscribed within limited coordinates, I could create a language to speak of problems with wider meanings, like power and vulnerability.

One thing is Nelson Mandela square, another is my Mandela project. The square is the seed of my series, but my series can’t be reduced to it. Despite its hostile appearance – a concrete tombstone with no vegetation and scarce furnishings – Nelson Mandela square hosts forms of public life: people go there to meet, play, chat… It’s like, no matter what, they refuse to abandon it. My project explores the invisible mechanisms underneath all of this.

The people we see in the Mandela photographs are mostly non-European. Why is it so?

In Madrid there is a tendency of creating ghettos for those people with fewer resources. Mandela square is one of such containers. The individuals I observed more closely are those who spend most of their time in the square alone. Sometimes they do so to escape their claustrophobic homes, sometimes because the square is where they sleep, out in the open. These people have talked to me about their lives and the neighborhood, and accepted to be photographed. In almost all cases, they are migrants.

Another reason is that the work references the idea of universal city, a concept inspired by the early urban formations that developed in Mesopotamia.

The images of Mandela are tightly framed and often taken at an angle. Can you talk a bit about your approach to the work, visually speaking?

This way of framing is a metaphor for how security cameras record life in public spaces. More importantly though, it creates a feeling of confinement, a subjective place with no horizon and limited perspectives.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Mandela?

When I was a teenager I read 1984 by George Orwell, and I think that read marked me forever. Recently I also read Arturo Barea’s The Forging of a Rebel, which made me appreciate my city and those who live in it. The psychological and social description of the upper class made by Buñuel in The Exterminating Angel also helped me represent an encapsulated space. I could mention as well the transformation of the city in Walker Evans’ photographs, the innocence and moral of Carlos Saura’s film Raise Ravens, the girl portrayed by Audrius Stonys on the way to the prison where her father lived, the garden in Lucrecia Martel’s The Swamp, all films by Aki Kaurismäki and in particular The Match Factory Girl, Mike Davis’ essays on urbanism and gentrification… All these references have influenced my work.

How do you hope viewers will think or feel upon seeing Mandela?

I hope everyone finds meaning in the images on their own. I wish the work helps them open their mind and widen their perspectives, but that’s not always possible. It’s enough for me if the pictures create an emotion.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

The most direct influences have to do with my process of learning photography through trial and error, as well as reading books about photography. In this sense, my master has been photographer Fosi Vegue, who taught me how to read beyond the obvious works of Robert Frank, Josef Koudelka, Bruce Davidson, Boris Mikhailov, Richard Billingham, Zoe Strauss, John Gossage, Ulrich Gerbert, Donovan Wylie or Eugene Richards. I was also influenced by the way of looking of Martha Rosler, Susan Sontag, Jo Spence, Nan Goldin and the Russian avant-garde.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Paul Graham, J. Carrier, Florian van der Roekel, Antonio Xoubanova, Federico Clavarino, Viviane Sassen, Mónica Haller.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Mandela. Mental. State.

Keep looking...

Men Don’t Play — Simon Lehner Investigates Masculinity on the Fields of Simulated Wars

Janne Riikonen Portrays Sweden’s Top Graffiti Writers

FotoFirst — Tianxi Wang Finds Solace Walking (and Photographing) Along the Hai River

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2019

Francesco Merlini Wins the Series Category of Void x #FotoRoomOPEN

The Baby Tooth Isn’t Loose — Brendon Kahn Captures the Fault Lines in Human Nature

FotoFirst — Simone D’Angelo Interprets the Story of the Monster of Florence, Italy’s First Serial Killer