FotoFirst — Tourism, Romance and Identity Come Together in Farah Foudeh’s Series ‘Just Because I Don’t Cry Doesn’t Mean I Am Strong’

Premiere your work in FotoRoom! Show us your new work and get featured in FotoFirst.

Just Because I Don’t Cry Doesn’t Mean I Am Strong by 28 year-old Palestinian-Jordanian photographer Farah Foudeh is a series of images shot in Petra, a renowned archeological site in Jordan. “The project is about how the waves of tourists coming to Petra have been influencing and changing the local Bedouin community” Farah explains. “It is about the bonds and relationships that are created between tourists and Bedouins on a personal and social level.”

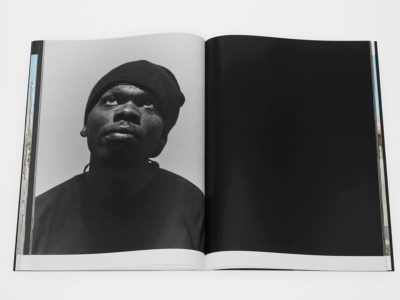

Petra hasn’t always been a major tourist destination. The local tribes used to live within the archeological compound, and it was only after the site was inscribed as a UNESCO world heritage site in 1985 that they were relocated to a small town outside the site. In Just Because I Don’t Cry Doesn’t Mean I Am Strong, Farah focuses on the impact of tourism on “the young generation of men that have grown up outside the walls of the caves and within the mass waves of tourists. With them I explore a journey of self-discovery. The series is therefore about the visitor and the host, and the relationship formed between the two.”

This is not the first time Farah explores the effects of tourism on local Jordan communities: “My previous work ‘Bedu’ was about the influence of tourism on the Bedouin community of the Wadi Rum valley; however, unlike the subjects I photographed for that project, the Bedouins in Petra were not playing on pre-conceived, traditional ideas of who Bedouins are and look like. Instead, the younger men of Petra have developed a unique identity and style to express themselves—a style that attracts the attention of visitors to the city, and ignites romances and stories that spur across other communities related to tourism in Petra. There is romance in Petra and you can feel it everywhere, from the hotel rooms, to the caves and mountains. During my process, and as I got to know the men and the area, I became more and more intrigued by this hazy line between the real and the performative, and wanted to continue to explore this space.”

“This is not just a story about the men in Petra, though” Farah continues. “It is as much about us all, visitors to places and our role and impact on them. I hope that my work sparks interest and creates an awareness on the importance of understanding the long-term impact of tourism and experience-driven travel. I know it may be a lot to ask, but it would be a start if people began to analyze what their role in other places might be. What sort of power structures guide their relationship with tourism communities around the world? Which elements are real and which are performative? How does one’s presence there affect or inspire these performances?“

Farah has visited Petra several times over a period of two years. “During my earliest visit, I was focused on experiencing the place photographically, on meeting people in person and then placing them in front of my lens. I initially met the guys inside the archaeological site during a very hectic high season in April, and I instantly fell in love with photographing them. Their energy and presence in front of the lens was dominant: they have grown up with cameras pointed in their faces and are not afraid to perform. It was easy to connect.”

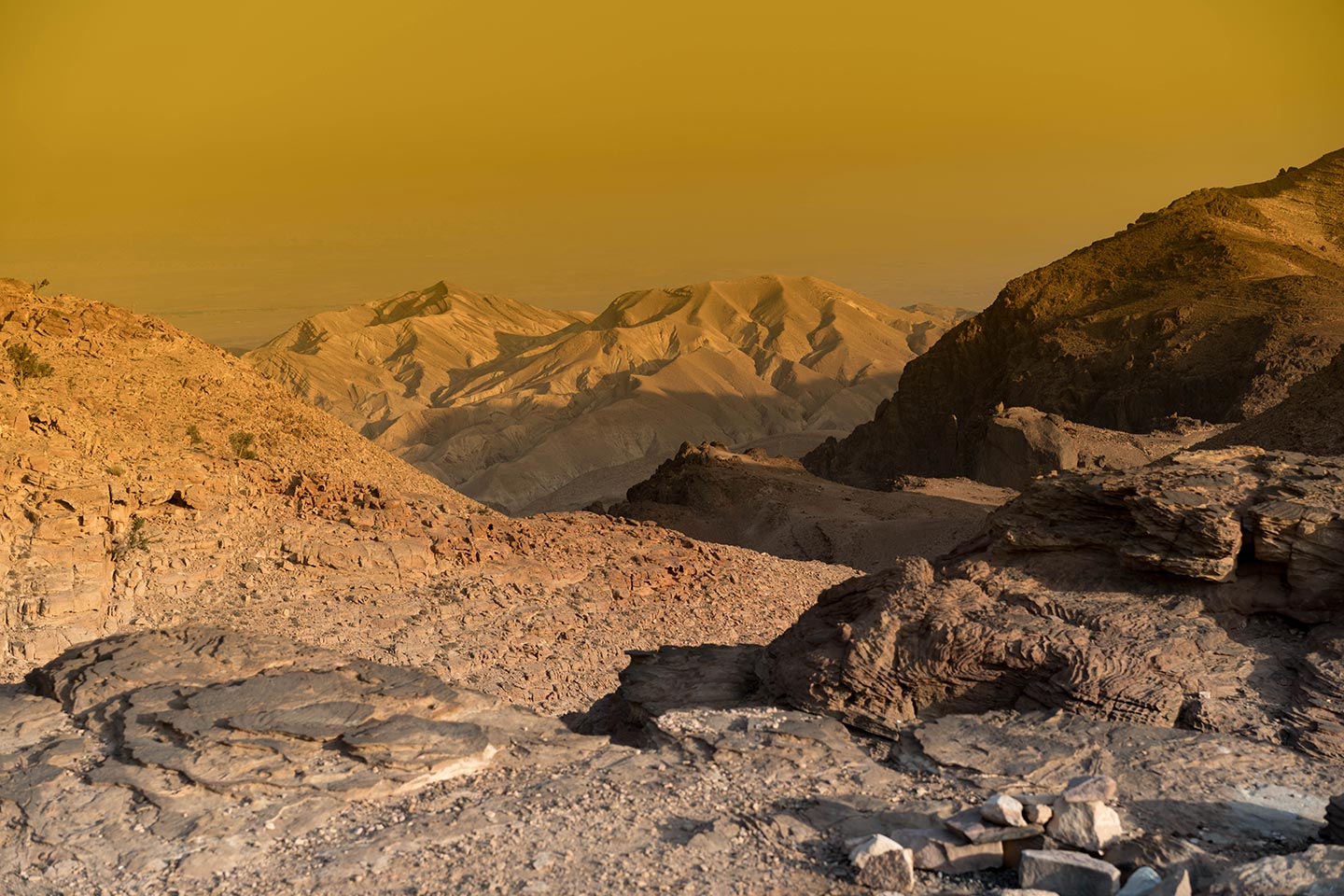

“During my second visit, I wanted to build on this and thus focused my attention on creating an atmosphere of a small-scale production, working with all sorts of lighting and gear as well as an assistant. I was eager to get more out of the young men, so as to make images that really exaggerate this notion of performance within the context of tourism. We drove out into the mountains surrounding Petra, set up lights, played music loudly and smoked cigarettes while shooting under the hot golden rays of the sun. It did turn into quite the spectacle and we all really enjoyed the image-making process. After that we all sat by a fire and had some sweet sugar tea, looking out into a sea of stars. I could now see how easy it would be for someone to be taken away by the lifestyle in Petra and everything that comes with it. It is only now that I can look back and realize those were the moments I was falling for Petra. I started off this project with clear images in my mind, but the more I visit, the more I am led by the feelings brought about by being in this strange yet wonderful place.”

Of the images, Petra says that “I was initially interested in very performative images. I wanted to explore and speak about the photographic relationship of tourism with host communities. People in Petra are photographed countless times a day, everyday, all year round. I was eager to express that strong presence that I, as a visitor, felt behind the camera. As I began to spend time, to explore, to connect, I became more and more intrigued by the feeling of Petra. The city exudes an undeniable, strong and sometimes aggressive sexual energy—an energy that felt somewhat intimidating at times, and at other times was just like any other day in the life of any woman. I wanted my images to convey these feelings. I was drawn to the kitsch hotel rooms in Wadi Musa and imagined the stories their walls could tell. Lust and love in Petra pour out into the surrounding hills and communities. I could feel it in the interiors of the rooms and wanted to show what was going on outside the ancient city. I focused on capturing and transmitting the feeling of being inside these rooms. Aesthetically speaking, I was interested in the kitsch feel of modern Petra: the bright neon colored lights, tacky rosy blankets and marbled interiors of the newer hotels in Wadi Musa. I wanted to transmit the transition of the communities primarily through their aesthetic and therefore focused on the colors I saw and felt in and around Petra, moving away from the rosy daylight hues single-time visitors of the city experience.”

“As I visited more often, I became drawn into the darker layers of Petra. I therefore moved away from photographing at sunset, choosing instead those twilight moments when the day begins to turn into the night, as the light fades into darkness, an overall sensation that I still sense as I continue to discover and feel my way around Petra: a place where sometimes everything seems clear, and other times, there is a strong sense of darkness that veils its reality. It is this feeling that I am hoping to transmit back to my viewers.”

In general, Farah is interested in tourism “because it serves as a microcosm of the world. It brings together a number of elements I find fascinating, like people’s relationship with photography: how we experience a place or people through image-making, how we represent our experiences and how they influence the places we visit. On a broader term, I am most interested in identity and trying to understand how people choose to see and represent themselves. As a result I am drawn to places in which the photographic process plays a role in understanding and transforming identity.” She is a “a huge fan of the works of Rineke Dijkstra and Paul Graham, “although recently I have been trying to distance myself from other photographers, trying to own my process without being influenced by outside work.” The last photobook she bought was Gülistan, a collection of archival photos of a party couple in Istanbul during the 1960s/70s.

Farah’s three words for photography are:

Show. Me. How.

Keep looking...

FotoFirst — Eleonora Agostini Has Her Parents Perform for the Camera in Uncanny Photographs

Ways of Escape — Antonis Theodoridis Photographs Athens in the Harsh Mid-day Sun

How Love Changes — Jane Hilton Juxtaposes Portraits of Young Couples and Widows

FotoFirst — Terry Ratzlaff Portrays the People Looking for Sex Online

FotoFirst — New Cinematic Photobook Explores Residential Segregation in St. Louis

Tempora Morte — Lia Darjes Creates Painterly Still Lifes at Kaliningrad’s Roadside Markets

Rani Road — Saleem Ahmed Shares Poetic Photographs of His Parents’ Hometown in India