In Brutal Presence — Nicola Muirhead Portrays the Council Tenants of London’s Trellick Tower

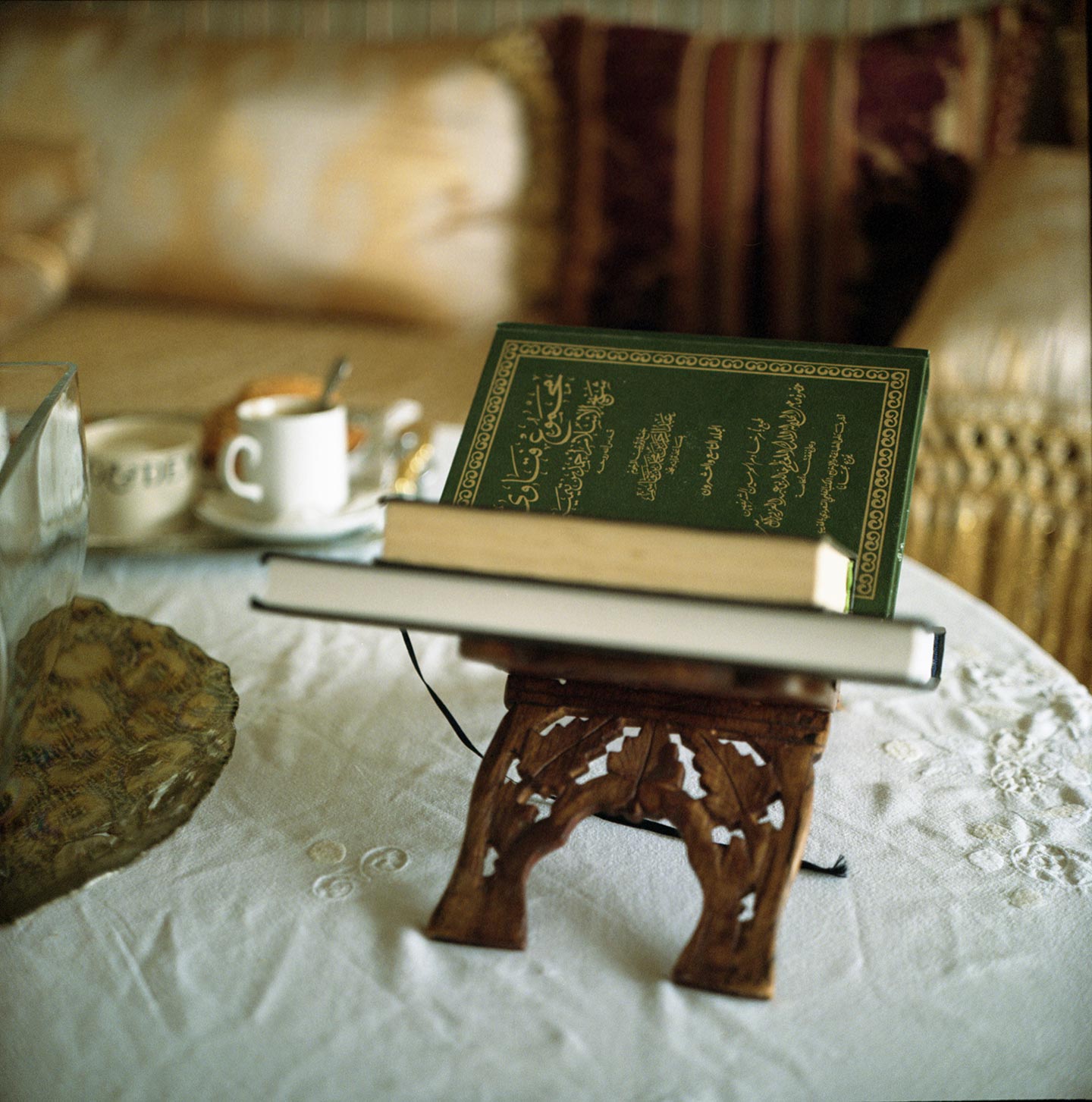

Last 14 June, a huge fire broke out at Grenfell Tower, a public housing building in West London, killing at least 80 people; since then, new questions have been made about London‘s social housing and whether council tenants live in safe conditions. With her long-term series In Brutal Presence, 31 year-old Bermudian photographer Nicola Muirhead brings us inside the flats of Trellick Tower—a social housing estate rising about one mile away from Grenfell Tower. Her environmental portraits show the diversity of people living in these residential buildings, and in light of the Grenfell Tower tragedy, the mind can’t help but go to the people who have lost their lives in the fire.

Hello Nicola, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Thank you for having me! I would say my main interest as a photographer are people and their stories, especially how those stories unfold within the context of current social and political paradigms. For me, documentary photography and visual storytelling are useful tools in reflecting truths back to us about ourselves, both collectively and individually.

In my work so far I have focused on topics related to identity, community and place. Future bodies of work will delve deeper into these themes, touching on ideas such as nationalism, generational trauma, and collective personas. Photography has also been a way for me to explore my role within these realities, and it gives me the opportunity to be present with myself and the people I photograph. This is what I truly enjoy the most.

Please introduce us to In Brutal Presence.

In Brutal Presence is an ongoing documentary project which seeks to highlight the realities surrounding social housing in London, beginning with the borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Using interviews and portraiture to narrate the story, this first part of the work starts with Trellick Tower—an iconic brutalist housing estate located in North Kensington which avoided the fate of demolition when it became a Grade II listed building [a UK classification which includes building to preserve for a special architectural or historic interest]. This protected Trellick from the neglect of the council, unlike so many other estates where tenants were decanted and replaced by private residential buildings.

The story is told through the perspective of the tower’s council flat tenants. These residents reflect on life within the estate and their thoughts and concerns in regards to the negative aspects of gentrification that can carelessly occur when these neglected estates are sold to private developers.

How do Londoners generally regard living in Trellick Tower and other similar public housing estates?

Generally I think public housing gets a negative reputation, which has resulted from years of neglect by the council. This inevitably has shaped public opinion about social housing. But now, in light of Grenfell Tower, people are paying closer attention to these tower blocks in a way they never had before. Londoners have woken up to the reality that these estates are under constant threat, and the people living inside are having to suffer the consequences.

What inspired In Brutal Presence, and what was your main intent in creating this series?

I was genuinely inspired by the immensity of the building itself when I first moved into West London. My intention initially was to illustrate the diversity of the community inside, pointing to the history of North Kensington and the generations of migrants from the West Indies and North Africa. But the story quickly shifted once I began to learn more about the disappearences of these estates and the fast decline of social housing stock within the borough, which threatens diverse communities such as Trellick.

What do the tenants you photographed think of living in Trellick Tower?

Collectively they all agree that Trellick is their home and community, one which they are proud to be living in. Trellick has in many ways shaped their sense of self and identity. The challenges they face in terms of gentrification will always be a threat, and the high cost of living in this borough makes it difficult to feel secure about the future. However, they remain resilliant and are a close-knit community within this built environment.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on In Brutal Presence?

Ponte City by Mikhael Subotzky was definitely a huge influence for me, as well as Robert Clayton’s Estate. But my biggest source of inspiration was actually a book by an author named Kevin Lynch titled Good City Form. He was an American urban planner and author, and his book was a real insight into the minds of architects and the philosophy behind these high-rise estates in post-war Britain. There is a kind of symbolism in their existence, which is especially poignant now that they are being torn down and re-developed.

How do you hope viewers react to In Brutal Presence, ideally?

I want the viewers to see the human element of these estates and to be concerned about their future existence. It is my hope that the viewer will feel “invited in” by the residents and their story, dispelling the negative stereotypes surrounding these brutalist estates.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

My style and approach as a photographer has evolved significantly ever since I started shooting on medium format film. This changed my whole way of seeing and because of this, I tackled denser subject matters over a longer period of time due to the very nature of film, and its slow creative process.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Laura Pannack, Jeffery Stockbridge, Greg Miller, Todd Hido, Olivia Arthur and countless others; the list is endless…

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Uncertainty. Intimacy. Connection.

Keep looking...

Theo Tajes Wins the Single Images Category of FotoRoomOPEN | foto forum Edition

Stefanie Minzenmay Wins the Series Category of FotoRoomOPEN | foto forum Edition

FotoFirst — Michael Dillow’s Photos Question the Idea of Florida as a Paradisiac Place

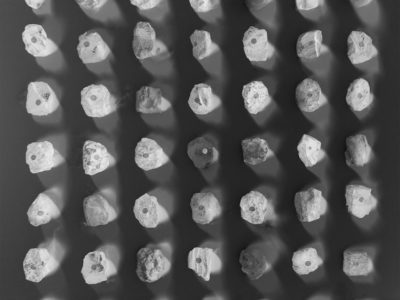

Private Companies Want to Mine Asteroids, and You Should Care About It (Photos by Ezio D’Agostino)

Karolina Gembara’s Photographs Symbolize the Discomfort of Living as an Expat

Robert Darch Responds to Brexit with New, Bleak Series The Island

Enter FotoRoomOPEN for a Chance of Being Represented by All-Female Photography Agency ACN