Sem Langendijk Documents The Squatters That Established Their Community in Amsterdam’s Docklands

We’re featuring this series as one of our favorite entries to the previous #FotoRoomOPEN call. (By the way, we’re now accepting submissions for a new #FotoRoomOPEN edition: the winner will get a three-month mentorship with London-based Wren Agency. Submit your work today).

Docklands by 28 year-old Dutch photographer Sem Langendijk is a documentary project that looks at how the unused dock areas of several international cities are being redesigned and repurposed. The project is divided into multiple chapters, one for each city; so far, Sem has worked in Amsterdam, New York and London. The images presented in this article belong to the Amsterdam part of the work, which is called Amsterdam (Agency).

Amsterdam is Sem’s hometown. In 1997, a group of people looking to create an alternative society squatted an abandoned shipyard in the city’s docklands, giving life to what they described as “a cultural free-haven”. “They had a mentality towards living together, and pursued the idea of being more free to decide what to do with their time and efforts. On a more practical level, they lived in temporary solutions—structures that could be taken away or deconstructed quite easily. They were aware that residing there without owning the land was a risk. In the twenty years they lived in that shipyard, they became an international known heaven for creativity, festivals and experimental living. All these activities were arranged along the concept of doing everything together.” The community was dismantled by the city of Amsterdam in early 2019.

“When Amsterdam’s docklands lost their function and were neglected, this kind of communities found the open spaces perfect to explore different ways of living, while staying in touch with the city” Sem says. “This is important, as it distinguishes them from hermits who try to escape society: these people were very involved in Amsterdam, they just wanted to offer a different voice. Questions about ‘the right to the city’ become part of the discussion, as does the concept of the ‘inclusive’ or ‘exclusive’ city. One thing I’m interested in with this project is the function and role of a community in processes of urban redevelopment, and how much influence they have on their direct environment. Cities tend to develop according to larger forces—I think the fascinating part of the ADM community was their will to be an actor in this process, to determine their direct living conditions and space. This is why I used the word ‘agency’ in the title: they challenged the powers in place. I’m interested in the outcomes of these power struggles.”

When he started working on this series of images, Sem soon realized he had to focus on the members of the community: “It was clear the area was mostly defined by the people rather than the space itself, so photographing them became something important to me. I was searching for a tone of voice that showed the people as strong individuals, photographing them with respect.” He felt a special connection with the children of the ADM community: “I grew up in a former railroad station, so my background is similar to theirs. The children in such communities don’t choose this way of life. It is a given for them to grow up in the environment that surrounds them, so when these families have to relocate, they are the most affected as they loose their reference to ‘home’.”

Sem hopes his work communicates “an infinite fascination and curiosity towards these communities, and I hope it can be viewed as a longing documentation of something that is under appreciated. I know the viewers of this work often look at these people as strangers, ‘others’ whom you do not easily relate to due to their appearance or ways of living, but I hope my photographs spark the same amazement and curiosity I felt for them.”

As a photographer, Sem is interested in “how we deal with space and how the landscape around us influences our consciousness. The landscape and the people that are present in it are a combined interest, as I like to see how they co-exist. How an environment (be it rural, urban or sub-urban) is affected by changing ideas are things I like to research through photography.” The greatest influences on his photography have been the documentary work of American photographers such as Joel Sternfeld and Walker Evans, as well as “the seemingly simple but clever photography that works with repetition and typologies, which uses comparisons to communicate. I like to study these ways of working and combine things when possible.” The last photobook he bought was One Wall a Web by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, and the next he’d like to buy is In Sardegna by Guido Guidi.

Sem’s #threewordsforphotography are:

Find. Your. Voice.

Keep looking...

Announcing the Winners of Our ‘Visual Storytelling’ Open Call

Where Does That Flower Bloom — Conner Gordon Confronts Memories of His Deceased Grandmother

FotoFirst — George Selley Recreates a Spy’s Life Based on Leaked CIA Documents

How Is Life? — Hannes Jung Explores the Unusually High Suicide Rates in Lithuania

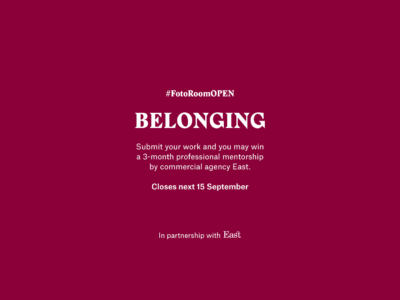

#FotoRoomOPEN — Enter ‘Belonging’ and Win 3 Months of Career Guidance by East

Heather Burn — Mat Hay Shares an Unromantic Vision of the Scottish Highlands

Detroit Nocturnes — Dave Jordano Tributes the Small Shops Resisting Through The City’s Crisis