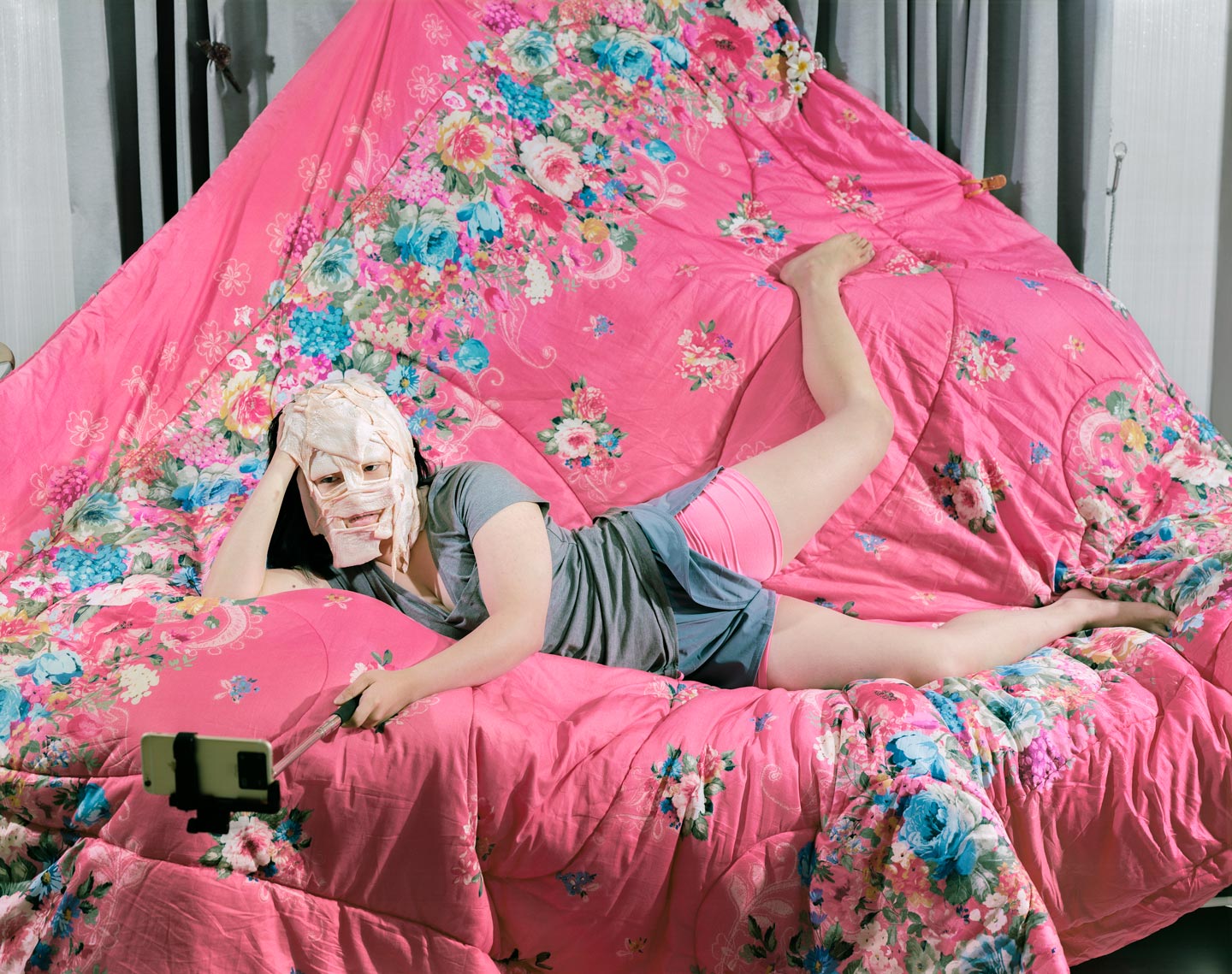

Bunda — Leonard Suryajaya’s Colorful Portraits Hide a History of Discrimination and Distress

At a quick glance, Leonard Suryajaya‘s colorful, kaleidoscopic staged portraits from his Bunda series might impress you for being a bizarre joy, and possibly even bring a smile. But as the saying goes, all that glitters is not gold: these images actually deal with Leonard’s complicated and tormented personal history. A 28 year-old photographer, Leonard was born in a Chinese family based in Indonesia—another trait that might sound charmingly exotic at first, while in fact Indonesia’s Chinese community is not only a minority group but also discriminated due to the different ethnicity and religious beliefs by the rest of the largely Muslim population.

Hello Leonard, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Possibilities, limitations, chaos, harmony, contradictions, people. I initially fell in love with photography when I realized it allows me to express in ways that verbal language doesn’t. I grew up in a strict and confusing setting: speaking up and thinking critically were privileges I didn’t possess. Photography naturally became the tool to help me visualize a more familiar world and kick some ass.

Please introduce us to Bunda: what is the work about?

Bunda is a celebration of a complicated life. It centers around the role of women and motherhood in the midst of societal struggle for inclusion and diversity. Enlisting family members, students and youths from a local organization in Indonesia, I set up stages in their homes, temples, and schools for them to act out their traumas, fears, frustrations, and pessimism in hopes for a more hopeful rendering of the future, without disregarding the mess of the past and present.

What inspired Bunda?

I am aware of the fears one might have about the idea of foreign people. Being part of the Chinese minority that make up 1% of Indonesia’s population, I am a witness to and recipient of a history of violence and perseverance. My skin, my flesh, my mind, my sexuality and my identities are governed by forces that quiet my own experience of being in the world.

Bunda came about in the same spirit of perseverance in the face of hardship. With the increasing negative sentiments against Muslims, immigrants and minorities, I chose to re-visit my experience as a child to learn about the settings I am in. I was raised by a Muslim woman, my “other mother”, while my parents worked hard to provide for me and my sister.

I often felt tensions surrounding my family’s ethnicity and Buddhist belief in Indonesia, the most populous Muslim-majority country in the world. We had to flee the country in 1998 because of the increasing violence against Chinese people in a moment of socio-economic collapse. I remember my dad asked my “other mother” to act as the property owner of our home to spare it from being looted and burned down. At the same time, he also told us to be cautious of her because it would be very easy for her to flip on us. As a kid, it was really confusing: not having any context and full understanding of the sociopolitical situation threatening us, I was stuck between the opposing allegiances I had to make with the people I care for.

Naïvely, I thought moving to America would solve these discrepancies in the building blocks of my identity. I’ve come instead to realize that individual and social hardships do not exist in isolation. Regardless of their location in the world, oppression, persecution, ethnic cleansing, cultural distrust, and displacement are always present. But so is the need to form a distinct identity in the context of changing cultures. It is like the reruns of the same “unscripted” reality show with different formats and characters.

What was your main intent in creating this series?

My intent was to share my experience and the experience of those close to me to not only give us a voice, but also to speak to others around the world in similar situations. It’s really easy to feel small and undeserving, especially for being a minority or coming from a developing country. More importantly, constantly dealing with threats because of one’s complexion, or ways of being, is very demoralizing. I hope to create a space where my subjects and I can have a conversation and acknowledge the hardship and joy of our lived experience, and then extend it to the viewer. I suppose, ultimately, I want our stories to be remembered.

Can you share some insight into making your images? How did your creative process for Bunda look like?

I photograph with a large format camera on Kodak Ektar films. Traveling with my camera and lighting equipment is always dreadful, especially having to nurse boxes of films through multiple customs and different countries. I’m usually quite anal in the initial preparation process. With all of the hustle and time needed to set up an image, I embrace that everything I photograph is a stage.

Sometimes I have ideas of what I hope to see in the photograph, so I will usually start there. Most of the times these will involve my family. I think only seeing them once a year really helps: we are quite awkward in expressing love and tenderness towards each other; we want to hang out, but we always end up being on our phones. I also can’t help turning in to the role of the repressed straight Asian eldest son. I guess there really is nothing else to do but to make photographs together. It’s our way of bonding and spending time productively. And once I spend more time there and get used to the temperature and time difference, I become inspired by the place, stories and experiences I share with the people I meet. That’s when I get the itch to do something and not stop.

For Bunda, I traveled to my other mother’s village in East Java and my hometown, Medan. In the midst of visiting and working with my family, I was also a visiting artist at a school and got an opportunity to work with a local youth organization.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Bunda?

I wanted to make photographs that hold both elements of chaos and harmony in a single frame. Inspirations came from the place, discomfort of traveling and being displaced, desire for awesomeness, conversations with others, teaching, being a son, global affairs, feeling of defeat, a peculiar life.

How do you hope viewers react to Bunda, ideally?

Being tickled, confused, humored, discomforted and amazed so they ask questions. Hopefully, when they are confronted with these experiences in regards to ideas of other people they don’t know, they are compelled to ask questions to sincerely learn more about them.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

As a kid who spent most of his time imagining different possibilities and constantly playing out different alternatives, photography was truly a gift. Like what one of my dearest mentor, Robert Clarke-Davis who is still alive, always says, “photography doesn’t happen without life”. Or something like that.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

I’m pretty bummed about Ren Hang’s passing—I really adore his work. Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Nico Krijno, Daniel Gordon, Aimee Beaubien, Viviane Sassen, Yasumasa Morimura, Rachel Stern, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Dawoud Bey, Alec Soth, Lucas Blalock, Gina Osterloh, Jessica Labatte, Wolfgang Tilmans. I fucking love photography.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Access. Freedom. Ass-kicking.

Keep looking...

Adagio — Laura Ghezzi’s Poetic Images Respond to a Time of Change in Her Life

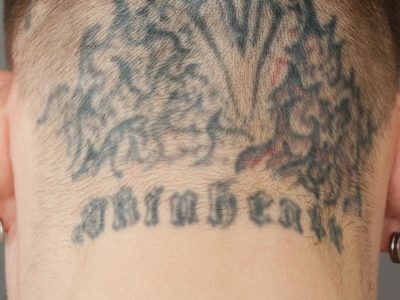

Jakob Ganslmeier Portrays Former Neo-Nazis Who Are Removing Their Nazi-Inspired Tattoos

FotoFirst — Michael Swann’s Series Noema Is Inspired by (Alleged) Apparitions of the Virgin Mary

In His Series Cicha Woda, Piotr Pietrus Collects Mundane Observations of Reality

Mirjana Vrbaski Shares Her Minimalist Portraits of Women from Her Series Verses of Emptiness

Giulio Di Sturco Captures the Alarming Conditions of the Ganges River in Stunning Photographs

Alvaro Deprit Creates Magical Images of Andalusia, His Family’s Original Homeland