Karolina Gembara’s Photographs Symbolize the Discomfort of Living as an Expat

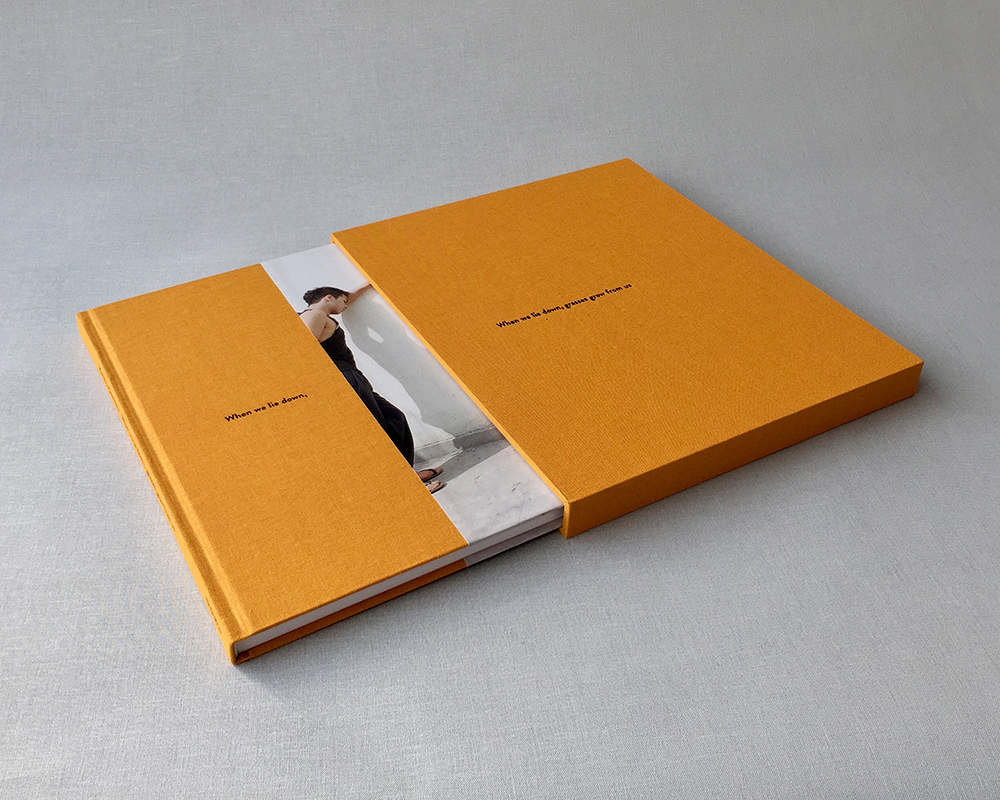

When we lie down, grasses grow from us by 38 year-old Polish photographer Karolina Gembara is a series of images Karolina shot in Dehli during the seven years—from 2009 to 2016—that she’s lived in the Indian city. The project is also available as a beautiful, recommended photobook recently published by GOST—buy your copy.

“In 2005 I graduated from International Relations and was offered a long internship at the Polish embassy in New Delhi” Karolina tells FotoRoom. “It was my dream to travel there—I imagined its lush gardens, wide alleys and jasmine scent. Luckily I had a pretty soft landing in the city: working in diplomacy kept me away from its dark and congested corners. I did my bit of traveling alone through Northern India, so at the end of my stay I still had a hunger for more experiences. I think my ‘real life’ in Delhi started 4 years later, in 2009, when I had an opportunity to go back. This time I stayed far away from the privileged foreigners’ enclave. For months I lived in the cheapest hostel in Dehli’s Tibetan village; it was harsh and I was lonely, but my photography project kept me going. By that time I was already disillusioned with diplomacy and changed my career. Being a photographer felt like a mission and I was up for all inconveniences and adventures. With time I met more and more people, made great friendships, moved in with my boyfriend. It seemed like I was adjusting well and started considering to relocate to Delhi permanently.”

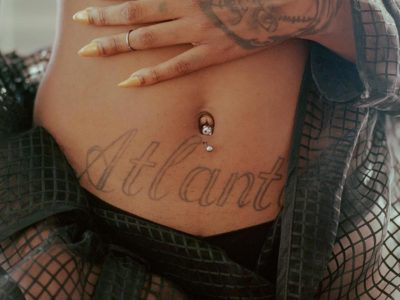

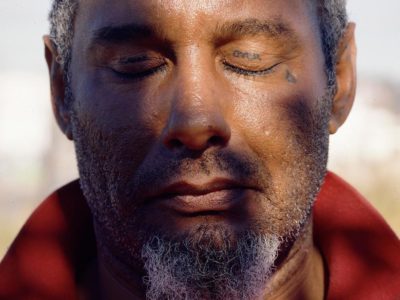

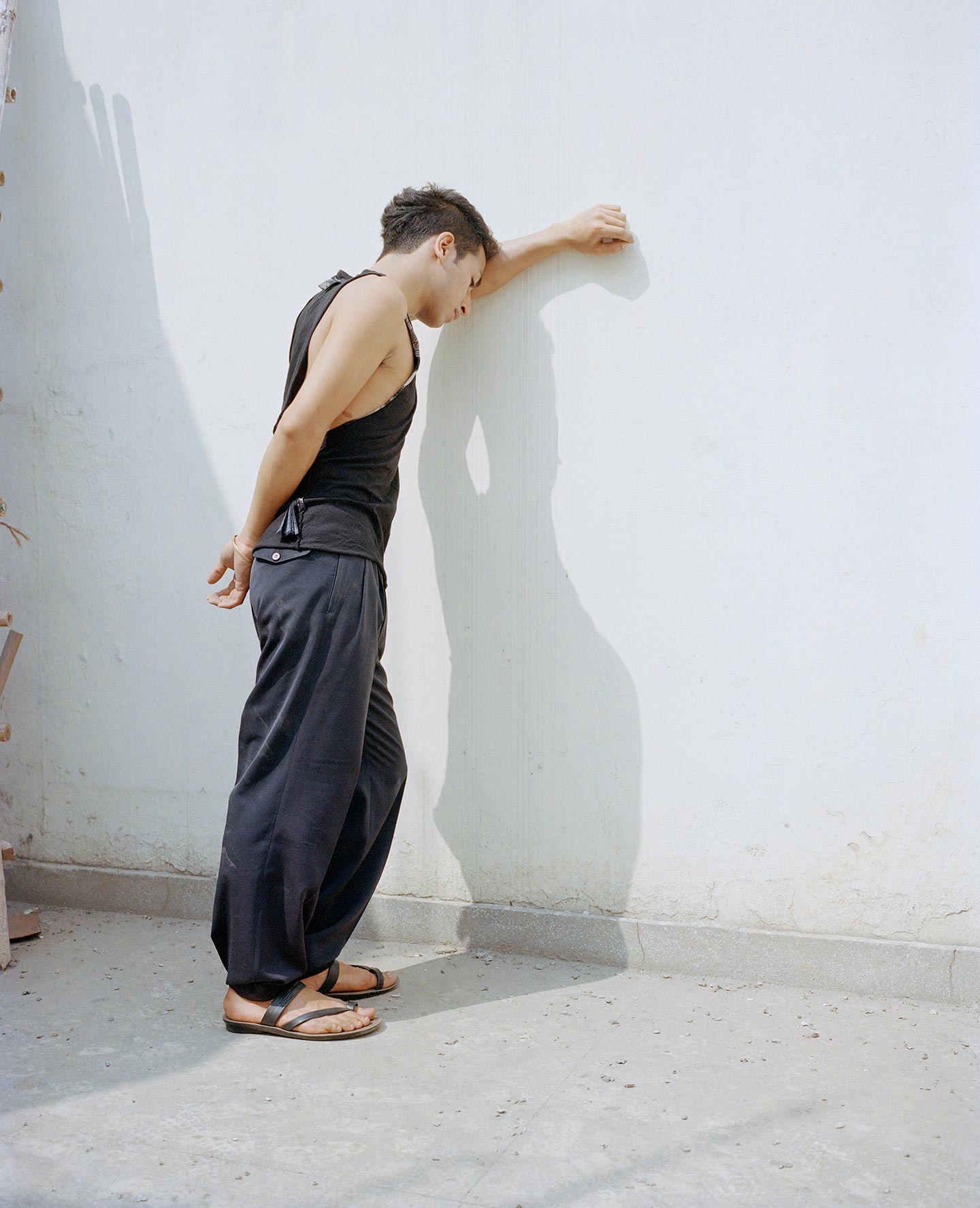

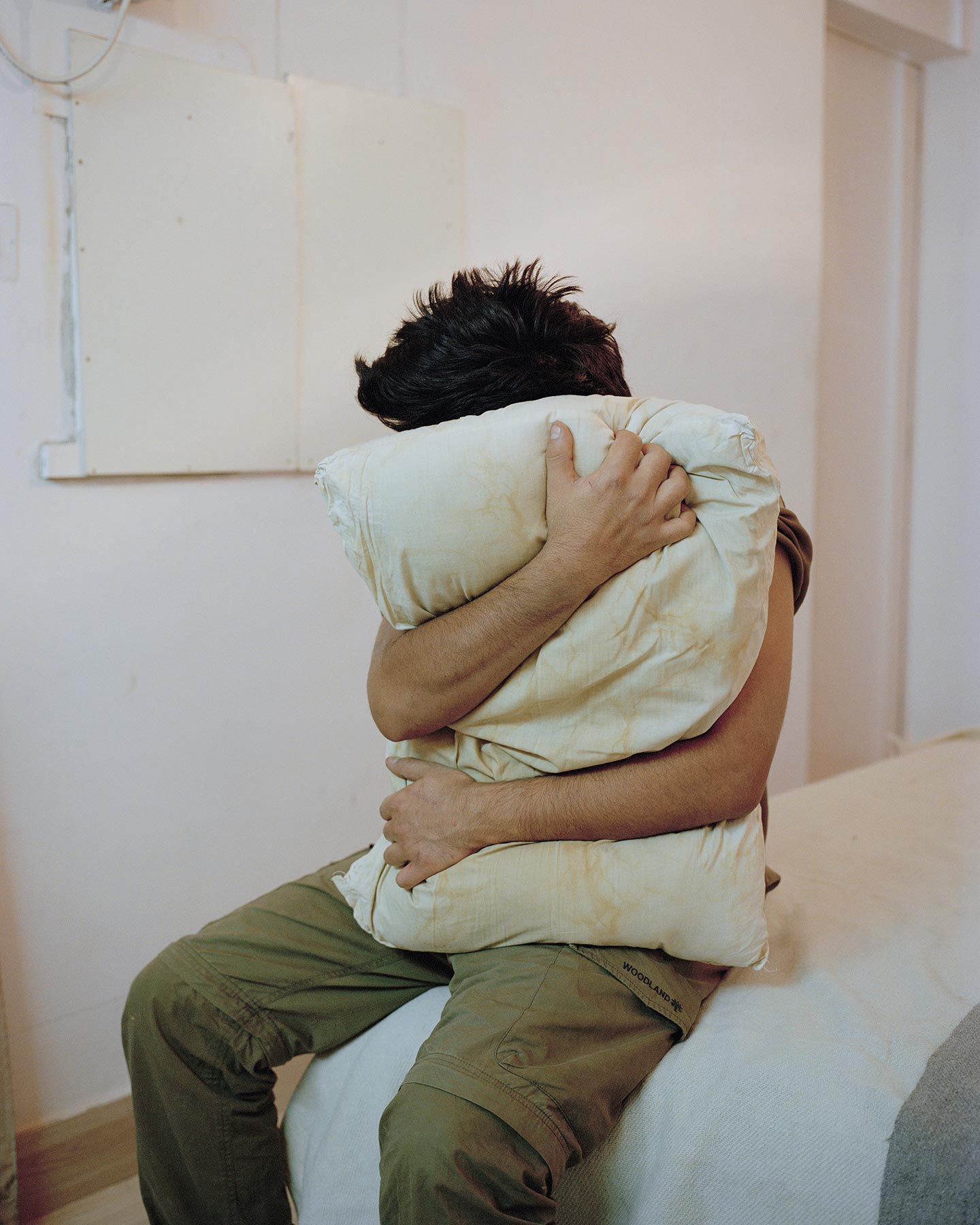

“As long as I thought of myself as a visitor, the brutality of life in Delhi—or India in general—was something I somehow turned a blind eye to. I saw children begging at the traffic lights and I was told ‘Ignore them’. But the moment I realized this could become my home, I felt like I needed to make things better around me. Or maybe I was simply saturated with the injustices and hardships I was witnessing every day. Moreover, I couldn’t get a job because I only had a tourist visa, so I had to travel back to Poland every couple of months. It was impossible to feel comfortable in Delhi, both physically and mentally: that unbearable sense of instability and loneliness eventually became the theme for When we lie down, grasses grow from us. My friends became my subjects because they were going through the same things, too: changing houses, experiencing superficial relationships, fighting the temperatures, looking for comfort… As a result the work was not about Delhi anymore but every urban, inhuman space and our struggle in it.”

Of the images, Karolina says that “from the very beginning I did not feel comfortable taking pictures of strangers, shooting on the street—something foreign photographers so often execute thanks to their/our power advantage. I have seen many shades of social structure in Delhi and though I was trying to educate myself I wasn’t able to understand what some people go through. I did not speak their language, I wasn’t in their shoes, and although I made an effort to empathize it wouldn’t have been fair to portray them. The only way I could stay honest was to turn to my friends, both Indians and expats, people I could share with, talk to, identify myself with. We were all living nomadic, makeshift existences and in a way we would probably experience the same ups and downs in any other metropolis.”

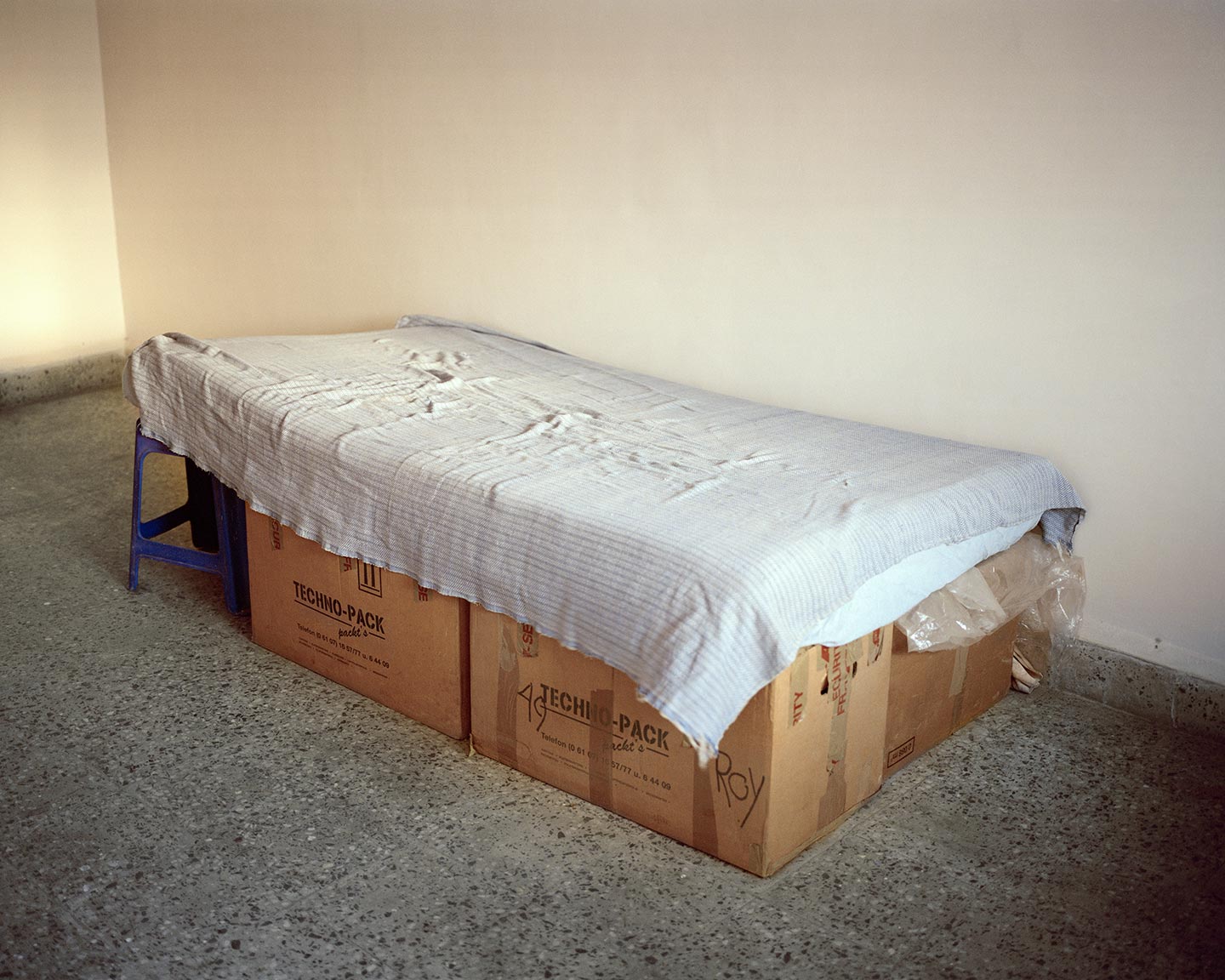

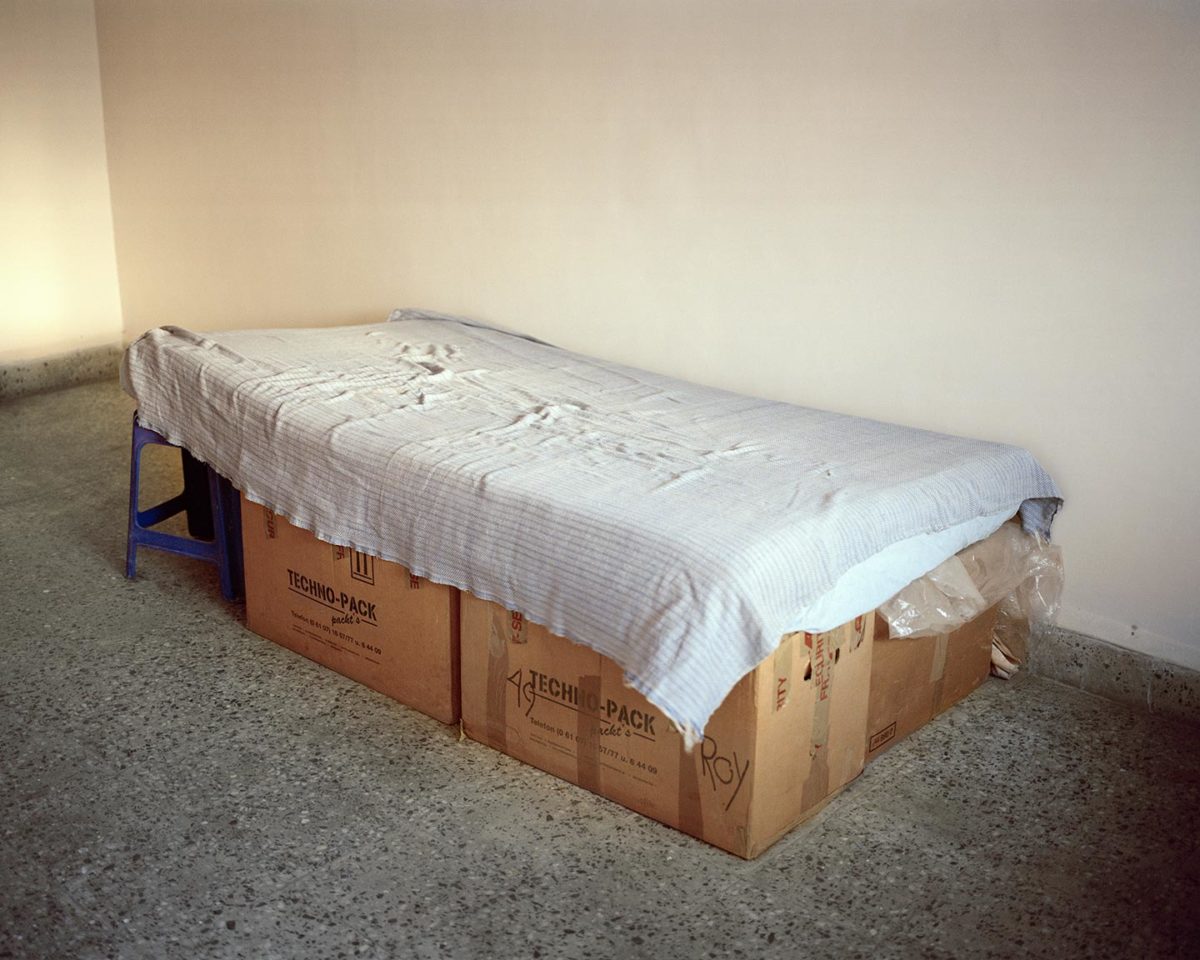

“Working mainly from home, with trusted individuals, I wanted to stage photographs that could metaphorically speak about our emotions. On top of that I would find objects and still lifes around our houses. Sometimes I’d recreate some situations and arrangements on my roof top. I’d often sketch frames and then photograph what was in front of the camera—two or three shots were enough as I knew exactly what I wanted. Yet, some of the images in the book are pure coincidences. The carton box bed with a wobbly mattress was something I saw in my friend’s house. I couldn’t ask for a better example of mediocre comfort.”

When she went to India, Karolina followed the advice of her teachers and started an inspirational notebook. “It has tear-sheets and quotes from such photographers like Olivia Arthur, Christian Patterson, Pablo Bartholomew, Susan Worsham, Claudine Doury, etc. I was interested in different aspect of this eclectic group, like Olivia’s vision of India, Susan’s portraits, Christian’s research. Specifically about visual language, my initial inspiration was Viviane Sassen, however I later became familiar with the post-colonial criticism of her work and I eventually rejected that approach. I mean, I still value her undisputed creativeness but I do oppose the sense of randomness and distance in books like Flamboya. I also wanted to be able to speak about socio-cultural aspects of India: I wanted my work to be grounded in a deeper, millennial or urban context.”

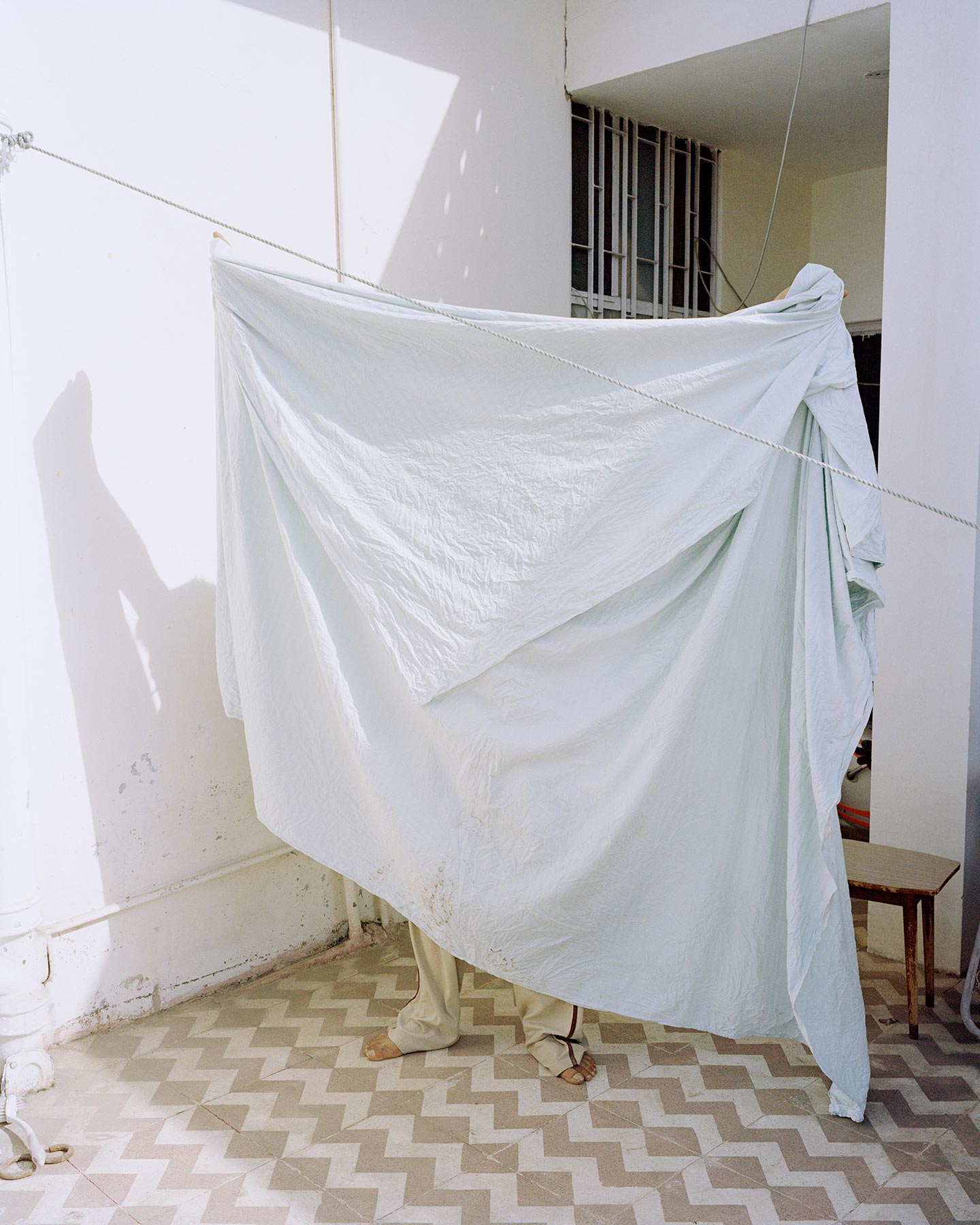

The When we lie down, grasses grow from us photobook is excellently edited and sequenced. “Perhaps like every photographer, after I was done taking pictures, I had no idea how to approach editing” Karolina recalls. “I had my ‘darlings’ that I wanted to include and was sure I was never going to give up on them. I attended a workshop on book-making with photography critic Jörg Colberg whose idea of making little vignettes or blocks of narrative helped a lot. Later on, Jörg offered his help and we came up with a sequence based on the previous attempts. This was when we decided to start and end the book with two pictures of crumbling interiors shot at a distance of a couple of meters from each other—that’s how far (or close) I went to trying to get familiar with India. Then there’s a few images interspersed in the sequence which show a man hanging a sheet up to dry, which I wanted to include because I think it portrays the struggle I’ve mentioned earlier. In general, I didn’t want the book to be a simple collection of portraits and objects. I made a dummy and tried my luck at contests; then I decided to turn to Ania Nałęcka-Milach, who’s the best photobook designer I know, and this is when my previous mentor and currently a friend and an artist I admire, Rafał Milach, stepped in and helped me get rid of my darlings. When we met with Stuart Smith from GOST, who eventually published the book, he suggested adding three or four images without destroying the main construct, which I really appreciated. So I have to say that the main body was there from the very beginning: I was lucky to work with Jörg and Rafał, and at no point I felt like I’ve compromised on anything.”

Ideally, Karolina hopes viewers react like Rafal Milach did when he first saw the work. “He asked ‘Where the hell is India in this project?’. He was actually relieved I wasn’t trying to talk about this immense topic but instead made an attempt to say something about the human experience with a very subjective narrative. I’m also always very happy to get feedback from Indian people, including my Indian friends who live in Poland but have the perspective of migrants trying to establish their lives in a foreign place. I had interesting reactions from people not involved with photography but who have been to India for work or other reasons. I think there is a certain mindset that makes you want to go there and look for yourself. Most people I know—the so called expats—do experience conflicting feelings towards India, and the book resonates with them.”

Karolina’s main interest as a photographer is to explore the idea of home. “At first I wanted to speak about home using personal stories, mainly that of my mother and her disease. Then it slowly shifted towards more universal aspects. Home is the central idea but I also explore themes that gravitate around it, such as the loss or the (mental) construction of a home. Therefore I also make work on migration, changing identities and places. In some recent work I included my family’s resettlement story only to speak about political problems in Poland and how we, as a society, lack compassion for those who are forced to leave their houses behind. Last year I also did a big participatory project with migrants in Warsaw. All the visuals were created by them. I think it’s very important that the ‘others’, who are now our guests and will soon hopefully become neighbors, can speak about themselves, using their sensitivity, and revealing as much as they please.”

The main influences on Karolina’s photography have been the work of the Sputnik Photos collective (of which she’s now a member), Viviane Sassen and the other photographers she’s already mentioned, conceptual artists like Broomberg&Chanarin, Taryn Simon, Tereza Zelenkova and Joanna Piotrowska, and the Israeli-Palestinian collective Activestills. The last photobook she bought was Hoax by Agnieszka Sejud, and the next she’d like to by is Here, Waiting by Maroussia Prignot and Valerio Alvarez.

Karolina’s three words for photography are:

Migration. Change. Identity.

Keep looking...

Selfies That Count — Matthew Humphreys Portrays Himself with His Alzheimer’s-Afflicted Father

People of Clay — Akshay Mahajan’s Images are Inspired by India’s Popular Myths and Legends

This Side — Erin Lee Gives Voice to the Mexicans Living along the U.S.-Mexican Border

Leah Edelman-Brier Confronts Her Fear of Becoming Like Her Mother in Brutally Honest Photos

Margarita Nikitaki Takes Claustrophobic Photographs of Athens’ Cityscapes

FotoFirst — Matthieu Litt’s Photographs of Iran Shine a New Light on the Secretive Country

Emily Kinni Portrays Just-Released Inmates Waiting for a Bus away from Prison