Dennis Dinneen, the Irish Town’s Photographer Who Had His Studio in the Back of His Pub

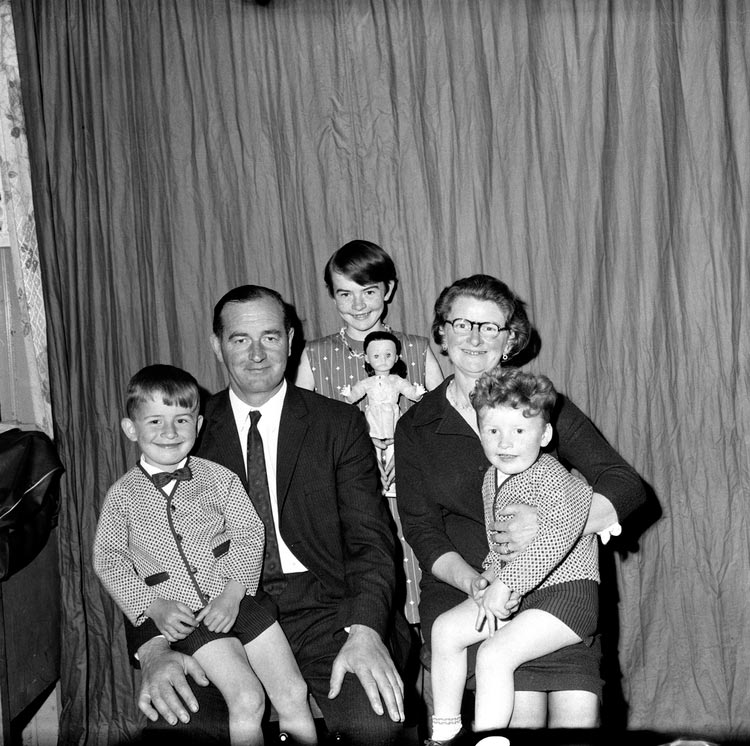

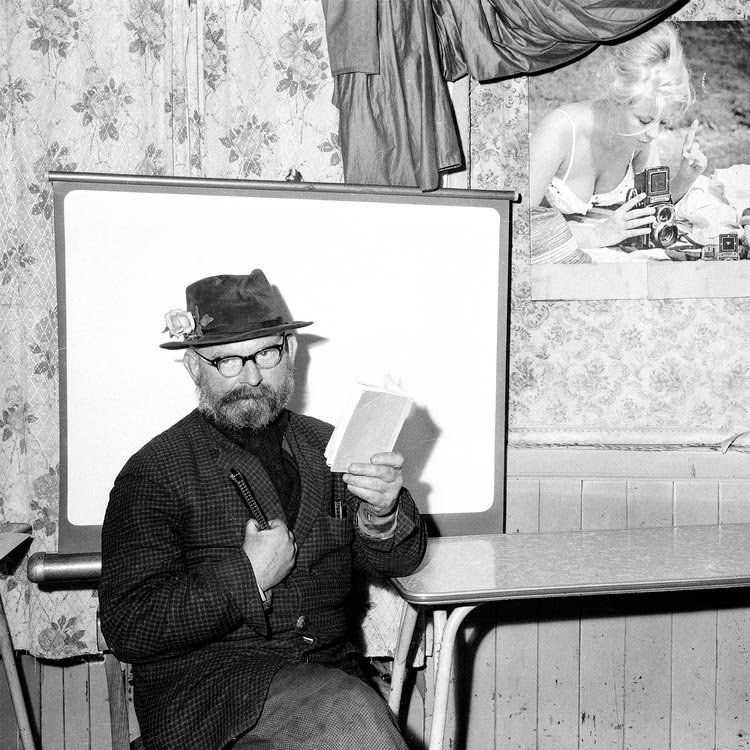

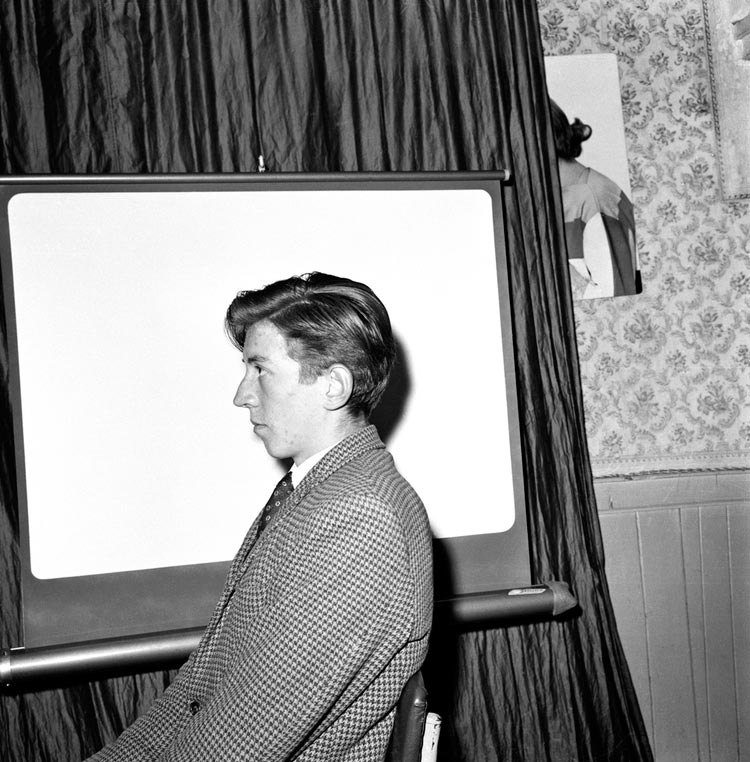

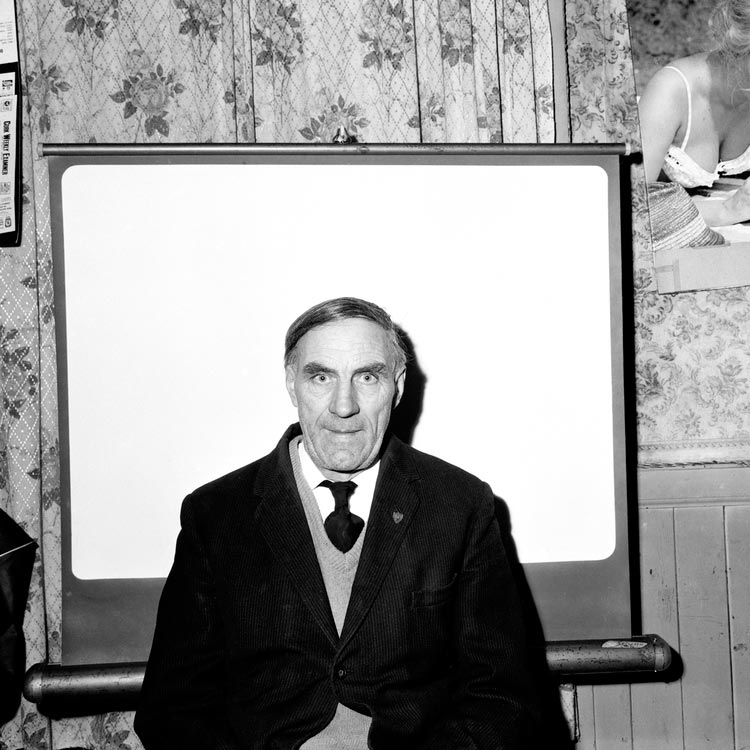

IN THIS INTERVIEW > Photographer and curator David J. Moore spoke with us about Dennis Dinneen, a professional photographer who had his portrait studio in the back of the pub he owned in the small Irish town of Macroom. David is currently rediscovering the huge archive of Dinneen, which consists of over 20,000 portraits and vernacular photographs that give us a peek into what life looked like in Ireland between the 1950s and 70s.

Hello David, thank you for this interview. Who was Dennis Dinneen?

Thank you, it’s a pleasure. Dennis was a pub’s owner and photographer in the town of Macroom in the County of Cork, Ireland. He ran Dinneen’s Bar, which also housed his small photographic studio and darkroom operating under the name Macroom Photographic Service, where he would make passport pictures and portraits for local people. Outside of the studio he covered everything from weddings, sporting events, pantomimes, religious ceremonies, trophy presentations and even documented crime scenes for the local police.

How did you come across Dinneen’s work, and why do you feel it’s important that it gets seen by more people?

I came across the work about 15 years ago. I lived in Macroom from 1995 to 2011 and the Dinneen family was still running the bar. The walls are covered in Dennis’ images of local characters, events, landscapes, etc. and I always found them very interesting.

In 2011 a local photographer, Seán Mac Suibhne, produced a book of over 500 images of Dinneen’s work for charity. It’s a fantastic collection of local images thats been hugely successful in the area. After seeing the book I became curious to see more. In 2013 I asked the family if I could have a look at the negatives. Once I started looking I was blown away by image after image. There were photographs I hadn’t seen either in the book or on the walls of the bar – the new work I was discovering, for me, was far more interesting than the rest. I became instantly hooked. I felt that there was so much more of Dennis Dinneen that needed to be seen outside of Macroom and outside of Ireland.

How would you describe Dennis Dinneen’s photography? What do you find most special about it?

That’s actually a hard question to answer! I would say his work is quite peculiar and has traces of humor in parts. Humor is somewhat hard to find in photography, and that’s what I find special about Dinneen’s work. I’ve shown some of the images to a few photographers, curators, writers and lecturers, and they all seem to share a similar opinion. Most have made references to people like Malick Sidebe, Disfarmer, Diane Arbus and even Martin Parr. But one thing that has been constant is that all of them have said they can’t quite put their finger on what it is about the work. There’s just something about it. Something that is just very ‘Dennis Dinneen’…

Is there any other photographic archive of life in Ireland between the 1950s and 70s that is comparable to Dinneen’s?

Yes, the most famous that I’m aware of is the Kennelly archive. It’s from roughly the same period and from the town of Tralee in Count Kerry, which is only about 2 hours away from Macroom. There are similarities in the subject matter and many parts of the two archives could merge seamlessly into each other. I think Dinneen’s stands out though with the abundance of both visually strong and unusual images.

A large part of Dinneen’s archive comprises the portraits he took in the back of his pub. Can you talk a bit about this type of images, and how do you think Dinneen approached them?

The pub itself serves as a strange place to go for your portrait or passport picture. I imagine some people could have had a pint or two to loosen themselves up before sitting for the camera. I’m fairly sure that it could also be some people’s first time in front of a camera or their first time experiencing flash photography. That leaves a mixture of subjects who are relaxed in front of the camera and others who are tense, or completely frozen. I find this fascinating and at times, extremely funny. He seems to have made images very casually. I get the feeling that he perhaps just used a couple of settings on his camera and flash at all times and a couple of set distances between him and the subject. This probably allowed him to finish pouring a Guinness and then walk down the back of the pub, pick up his camera and instantly take somebody’s driving license photo. He would later develop and print it in his small darkroom upstairs and crop it to size for the customer. The full frame however could be slanting or unbalanced with objects, signs, beer kegs and boxes jutting into them, but somehow they still have a good sense of composition. This is what makes the images so interesting.

Dinneen’s archive includes approximately 20,000 negatives and plates, which you are scanning with his son, Lawrence Dinneen. How is this huge process going, and what sort of emotion is it to go through image by image?

I must clarify that Lawrence has put in the most work when it comes to the bulk scanning and cataloguing of images. He began this long before I came on board with the project. I’ve been going through his digital scans and selecting and re-scanning important images along with printing and curating the recent show we had in University College Cork. We’re only about 6,000 in to 20,000 images. There are still untouched films in rolls, glass plates and even some unprocessed films. We have a long long way to go!

The whole process is very different for both of us. I’m approaching it from a completely photographic point of view as I have no relationship to the people in the images. I get excitement from discovering new pictures even though I know nothing about the people in them. It’s much easier for me to be critical and edit as I don’t have the connection that Lawrence does. For him it’s all very personal. He still runs the bar where these images were taken and there are people in the images that still drink there to this day.

Vintage vernacular photographs always exert a unique fascination on us – why do you think is that? Where does their power lie?

It depends on how much is known about the images we are looking at. I think a lot of that fascination can often come from the back story that comes with the photographer or archive, like in the case of Vivian Maier. That’s not to take away from her images, they are truly brilliant. But, I find the conversation tends to revolve around the back story and the discovery of the work rather than the images themselves. In cases where less is known about the photographer or image there is a sense of mystery. We are never fully sure what we are looking at. I feel the power in these images is a combination of this mystery and our ability to add our own narratives.

What future projects to promote his work are in the plans?

I’m currently looking to get some more exhibitions both in Ireland and abroad but don’t have anything tied down yet. We have been speaking to a few publishers and have a book in the pipeline too. Hopefully that will be out within the next 12 months.

Keep looking...

FotoRoom’s 10 Favorite Series That Premiered on FotoFirst in 2019

FotoRoom’s 10 Favorite Series of 2019

The 10 Most Seen Series on FotoRoom in 2019

Oleksandr Rupeta Captures the Relationships Between Humans and Their Unusual Pets

Cole Flynn Quirke’s Diaristic Photographs Document His Life After His Grandmother’s Death

Isabella Akers Rebuilds Her Relationship with Her Father by Photographing Him

FotoFirst — Marcus Glahn Photographs the Last Transylvanian Saxons of Romania