These Apparently Ordinary Places Hide a Horrible, Horrible Past

Photography is a tricky medium: its inability to use words creates voids or ambiguities that can actually be a strength in some cases, while at other times it represents a problem, especially for those works that deal with current news or historical events. It so happens that if you look at Makeshift, a series of images by 25 year-old Polish photographer Pawel Starzec, without knowing anything about the work, and then look at it again after discovering what the background of the work is, you will experience the images in a completely different way. So here’s what: have a look at the photographs first, then read our interview with Pawel to find out more about them. (We were suggested to take a look at Makeshift by photo editor Petr Toman. Would you like to make a recommendation as well? Feel free to reach out).

Hello Pawel, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

A question about my general interests is a hard one to answer, but to put it briefly, in my personal work I tend to focus on projects which depict a specific phenomenon from a peripheral point of view. I’m looking at the connection between a certain place and the social context around it. I’m way more attracted to the buildup and aftermath of an event than the event itself: I try to make sense of major circumstances through their outcomes and the marks they leave.

Please introduce us to Makeshift.

Makeshift is a project on rewriting history in general, and the history of the Bosnian War specifically. For those who have no idea of what the Bosnian War was, imagine a republic with different ethnic groups, each of which enjoyed a certain level of independence and recognition. People were living together, mixed marriages were commonly practiced, and no ghettoes existed. But then the war broke out, and those groups started fighting and ethnically cleansing each other. Detention and concentration camps were improvised in almost every city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in whatever building—mostly public—could house a large number of people.

After peace was reached in 1995 with the Dayton Agreement, which solidified the division of Bosnia into a federation of opposed states, the vast majority of those buildings were renovated and restored to the functions they were used for prior to the war: parents—those who had the luck to be in the same home they lived in before the war—found themselves sending their children to the very same schools where they had been severely tortured and beaten. Makeshift is a project about collective narrations being reset from scratch, histories being written and re-written to conceal and deny atrocities. By photographing the places and structures once used as concentration camps, or where horrible crimes were committed, I intend to underline the mechanisms which were the driving force behind the war.

What inspired Makeshift? How did you get the idea behind the project?

The project was inspired by a great non-fiction book by Polish reporter Wojciech Tochman: Jakbyś kamień jadła [tr. Like Eating a Stone] which deals with post-war exhumations in Bosnia. Back then I didn’t know much about the Bosnian War besides the Siege of Sarajevo. Since I’m a curious person, I started making some research and I came across a document produced by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague in which hundreds of witnesses gave detailed descriptions of the camps they had been detained in. I decided to investigate further about these places as a way to find out more about the war. The idea of showing the aftermath of the conflict rather than going for a more journalistic approach came up almost immediately.

What was your main intent in creating Makeshift?

I’m not a fan of the narrative of the savior-photographer who touches the hearts of the masses with his images of the darkest corners of the world. I think an artist’s biggest responsibility is to know what they want to do or say, and how to do or say it. Nowadays, being an artist is a hobby: you can’t expect help from anyone, as doing what you’re doing is your own choice. With that said, my intent with Makeshift—and most of my other projects—is to simply tell a story in the way I would like it to be told (and seen). If it also inspires any change, helps anybody, sparks any interest, then great.

The whole idea of showing the places where atrocities were committed rather than finding a more direct way to speak about those atrocities is also a message somehow: it’s a way to escape the never-ending photographic race for the decisive moment. It’s up to the viewer to imagine what happened. Also, I find the mechanisms that were at work during the Bosnian War are likely to reoccur in the present day, so it’s important to remember what they led to.

Makeshift is a good example of how a textual presentation is sometimes fundamental to explain the story in the images of a certain photographic work. How did you approach this “problem” while conceiving Makeshift?

The dilemma of how to connect the images and captions was the biggest challenge for me, one I’m facing again as I design the Makeshift photobook. The basic idea is to begin by presenting the places I’ve photographed as if they were “regular” and sometimes even scenic locations, and not giving the viewer any clue about what happened in those places, only to reveal the historical context at the very end.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Makeshift?

I strongly relied on official documents produced by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Although I don’t believe that true objectivity can be achieved in photography or any other art, dealing with a topic like post-war aftermath required strict fact checking. Besides that, I was generally inspired by how other artists have created narratives in a way that omits the direct exposure of the subject matter and rather focuses on details that the viewer must use to reconstruct the bigger picture. One of my major inspirations in this sense was On This Site. Landscape in Memoriam by Joel Sternfeld, a project that deals with the subject of violence in America through the marks it leaves on the landscape.

How do you hope viewers react to Makeshift, ideally?

As an artist, you can’t have control on how your work is received, so I usually try to avoid setting any expectations. But I hope that at least a number of people discovers what the Bosnian War was, and how it came about. I would be glad if viewers would be shocked even if the photographs lack any graphic violence: hopefully, the idea of what happened will be enough to horrify them.

Like I mentioned before, this project is also about history being a plastic matter and how those in power can use it to control people by controlling their culture. I find this a problem of our day and time as well, and strongly support any movements discouraging the rise of ultranationalism and the manipulation of history that fuels it. If Makeshift inspired someone to actively oppose the ideas that lied behind the war in Bosnia and that are resurfacing today, I would be more than happy.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

I’m really interested in the New Topographics movement—not intended as simply the original exhibition, but the broader circle of photographers who shoot with the same approach in mind. Whatever you call it—Düsseldorf School, or deadpan photography—that’s the approach I feel comfortable using when I photograph.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

The first time I was deeply impressed about the work of a photographer was when I saw Niagara by Alec Soth. His approach to storytelling and the way he swings between methodological organization of huge projects and short stories is constantly amazing me; but I have the feeling that praising Soth is a pretty obvious thing to do in contemporary, documentary-oriented photography. Besides him and Sternfeld, I adore the documentary works of Taryn Simon, Thomas Gardiner, Nicolò Degiorgis, Nadav Kander, Yaakov Israel, Larry Towell, Mike Brodie or Tamaz Dezso. From my country, I admire the works of Jan Rogalo, Michał Sierakowski, Paweł Jaśkiewicz, Kuba Rodziewicz, Adam Wilkoszarski, Krzysztof Sienkiewicz, Dominika Gęsicka, Natalia Dołgowska, Wojtek Wilczyk or Konrad Pustoła, whose posthumous monograph is the latest book I’ve purchased.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Memory. Evidence. Story.

Keep looking...

Theo Tajes Wins the Single Images Category of FotoRoomOPEN | foto forum Edition

Stefanie Minzenmay Wins the Series Category of FotoRoomOPEN | foto forum Edition

FotoFirst — Michael Dillow’s Photos Question the Idea of Florida as a Paradisiac Place

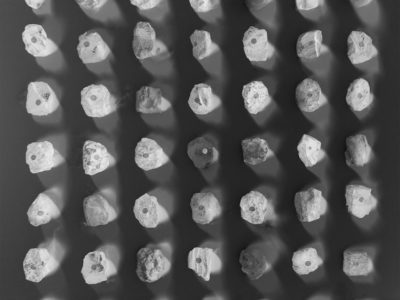

Private Companies Want to Mine Asteroids, and You Should Care About It (Photos by Ezio D’Agostino)

Karolina Gembara’s Photographs Symbolize the Discomfort of Living as an Expat

Robert Darch Responds to Brexit with New, Bleak Series The Island

Enter FotoRoomOPEN for a Chance of Being Represented by All-Female Photography Agency ACN