On Bricks and Humans — Why the Invention of the Brick Was One of the Most Crucial for the Mankind

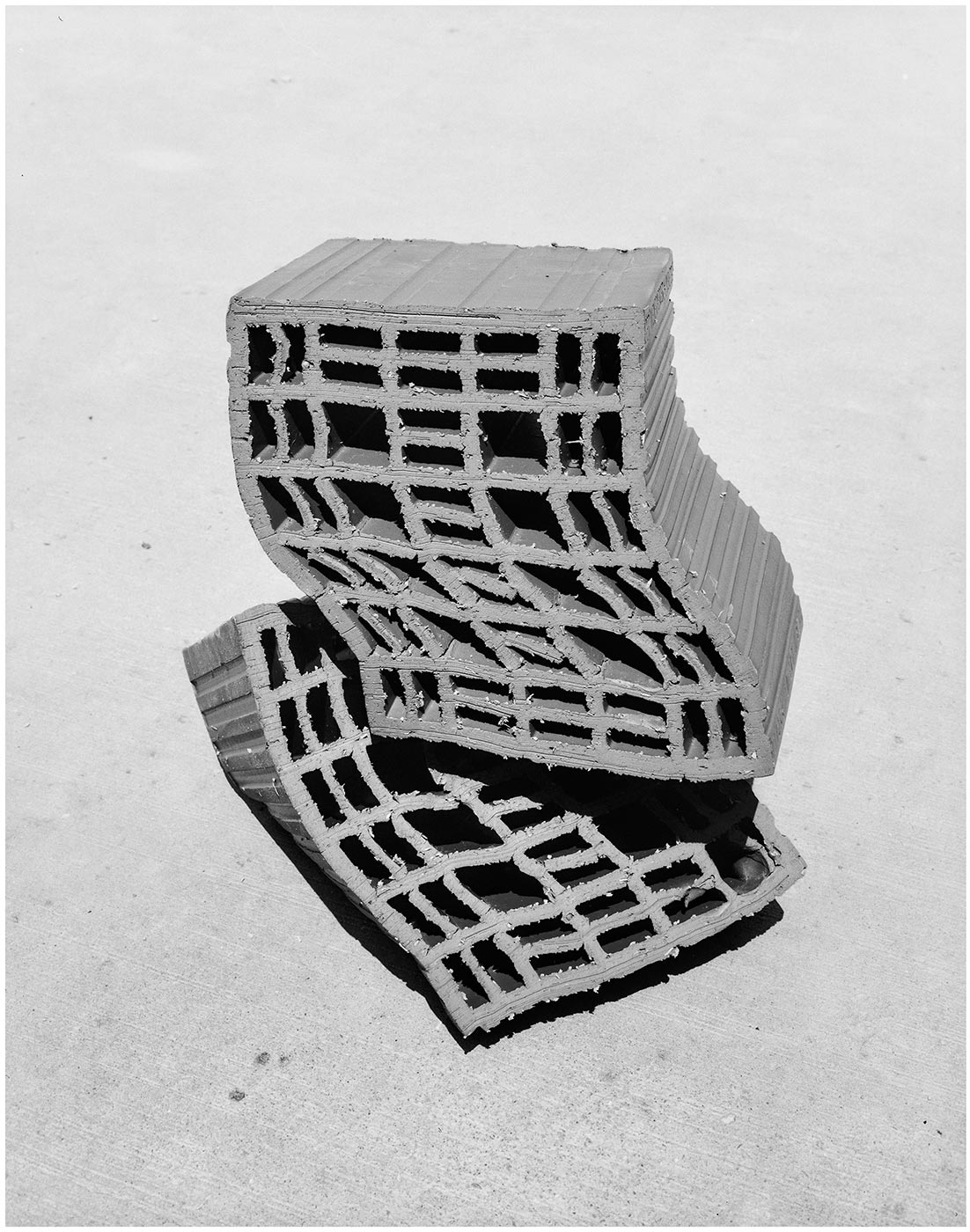

38 year-old Hungarian photographer Gábor Arion Kudász shares some background to Human, a very intriguing body of work that explores the humble brick as the trait d’union between mankind’s pre- and post-technology evolution.

Hello Gábor, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

It seems impossible to make a distinction between my personal and professional interests. I’m curious about all kinds of things, but in retrospect most of my works, even when I approach seemingly personal topics or portray certain individuals, examine how humanity operates as an organism. In fact, I don’t find photography in itself exciting at all; but it’s a great tool to understand the structure of the world.

Please introduce us to Human.

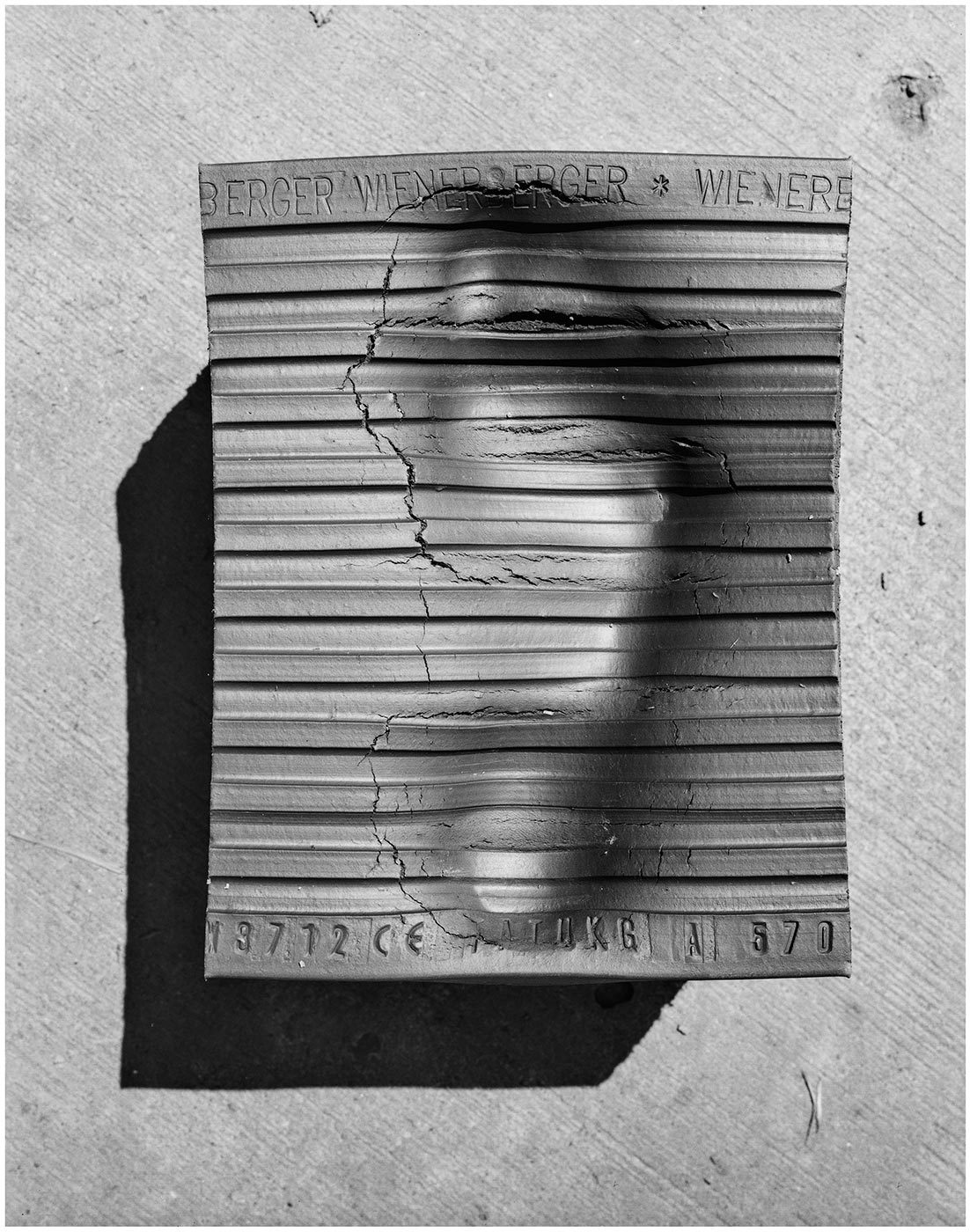

Human was realized in cooperation with Wienerberger, a major worldwide producer of building materials which regularly commissions photographers to create projects related to their activities. In early 2014 Wienerberger’s curator Moritz Stipsicz approached me to produce a set of new images for the company’s collection centered around the theme of the brick. The commission however opened a totally new perspective on my long-term artistic investigations. I believe what I came to find surpassed their and my own expectations.

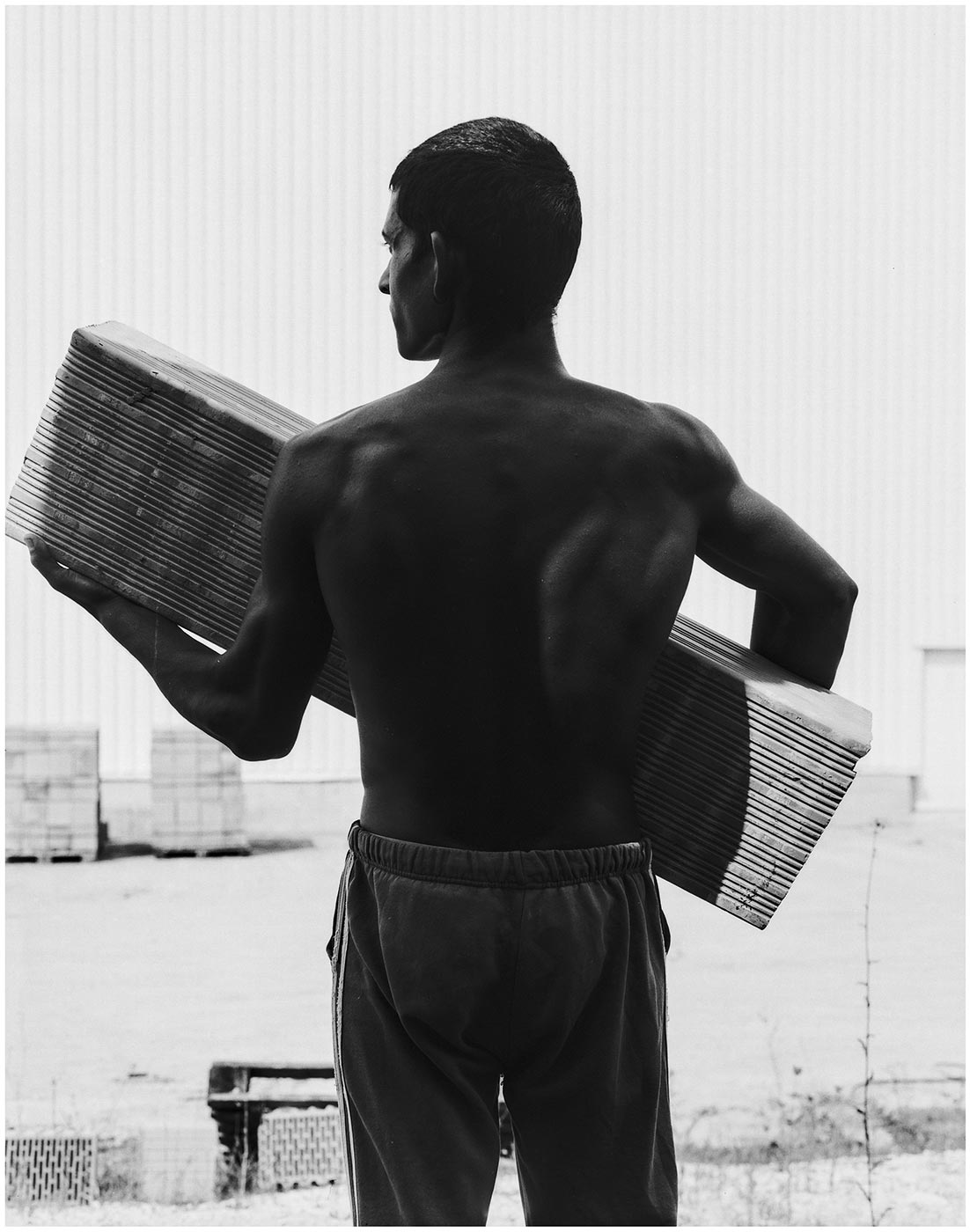

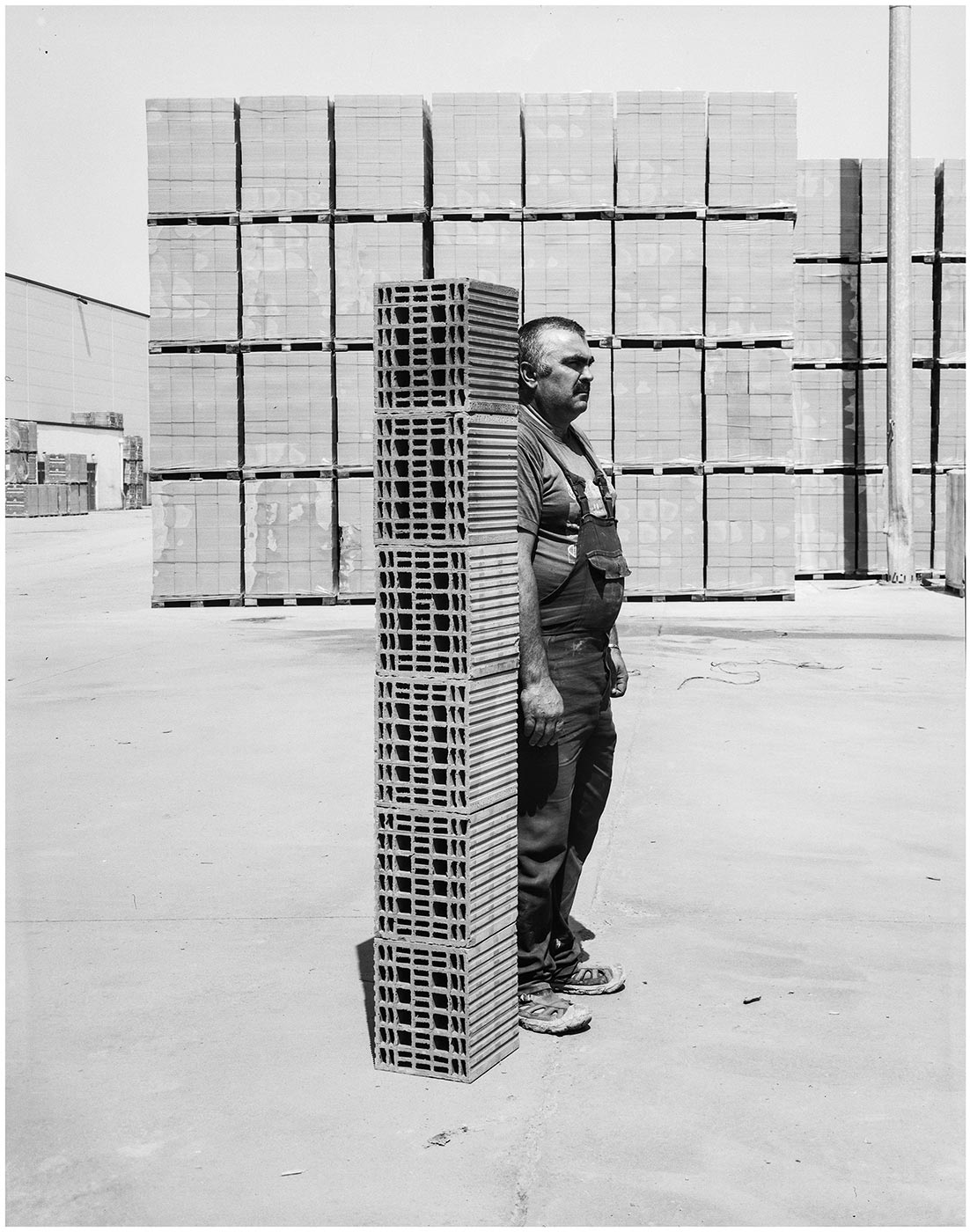

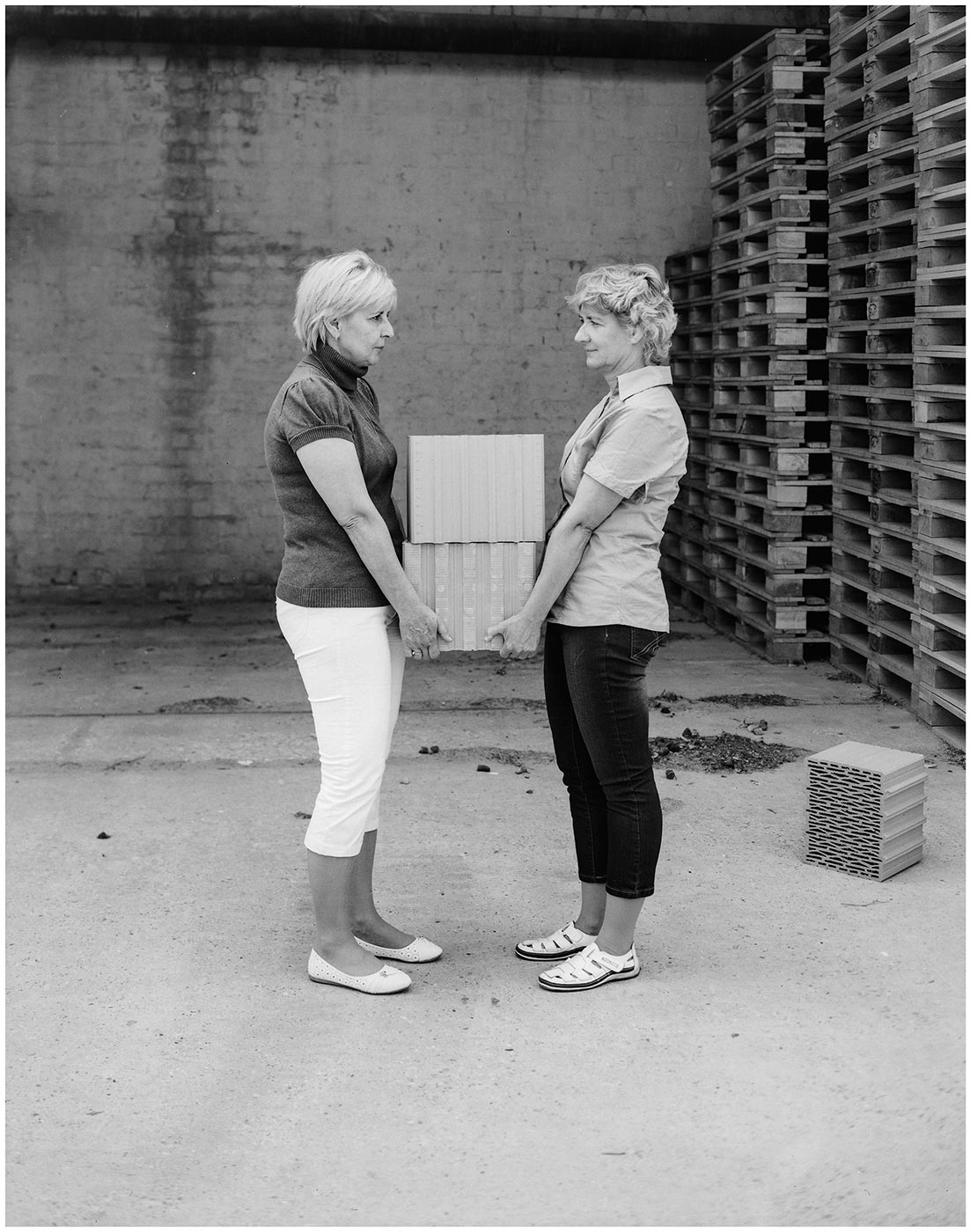

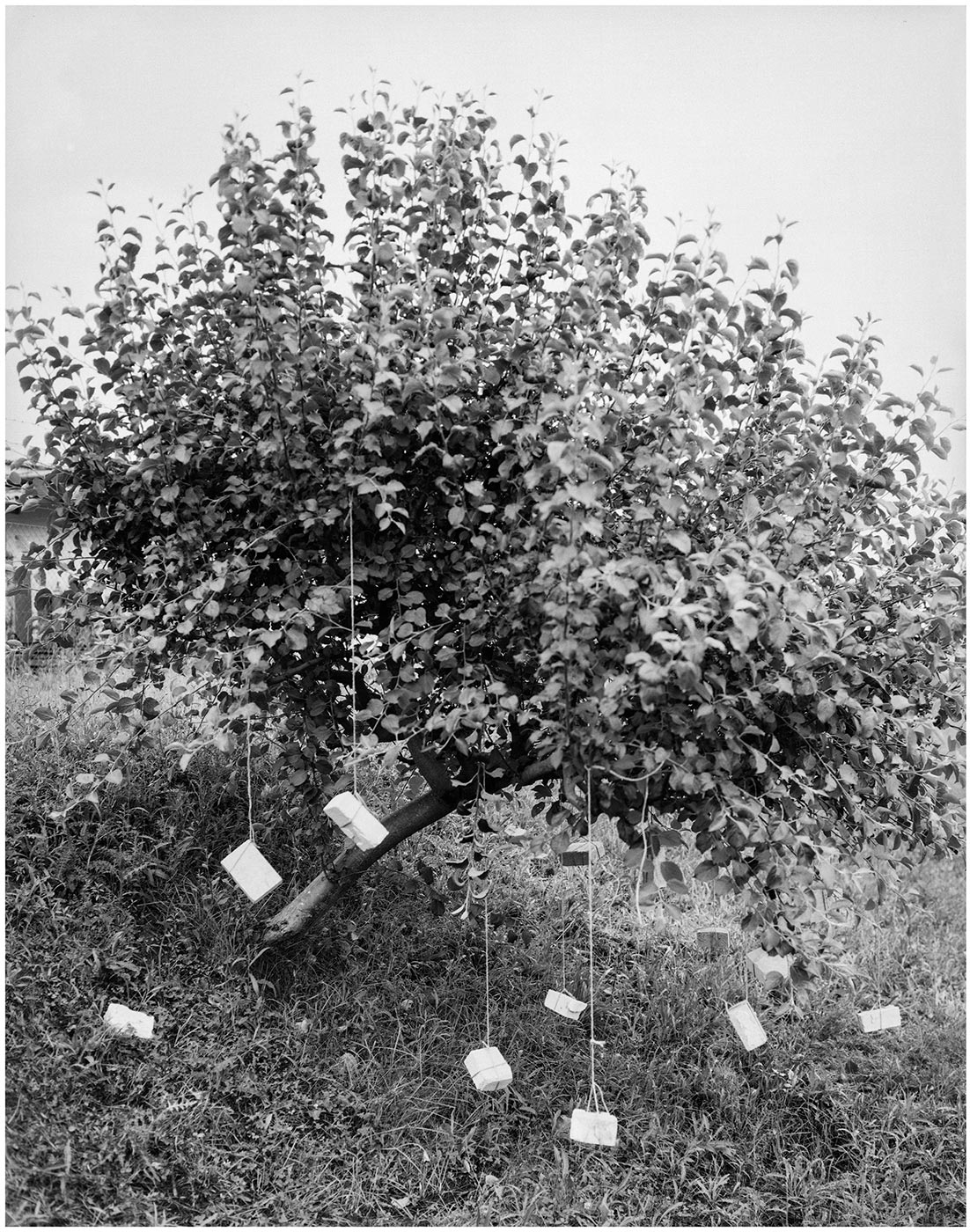

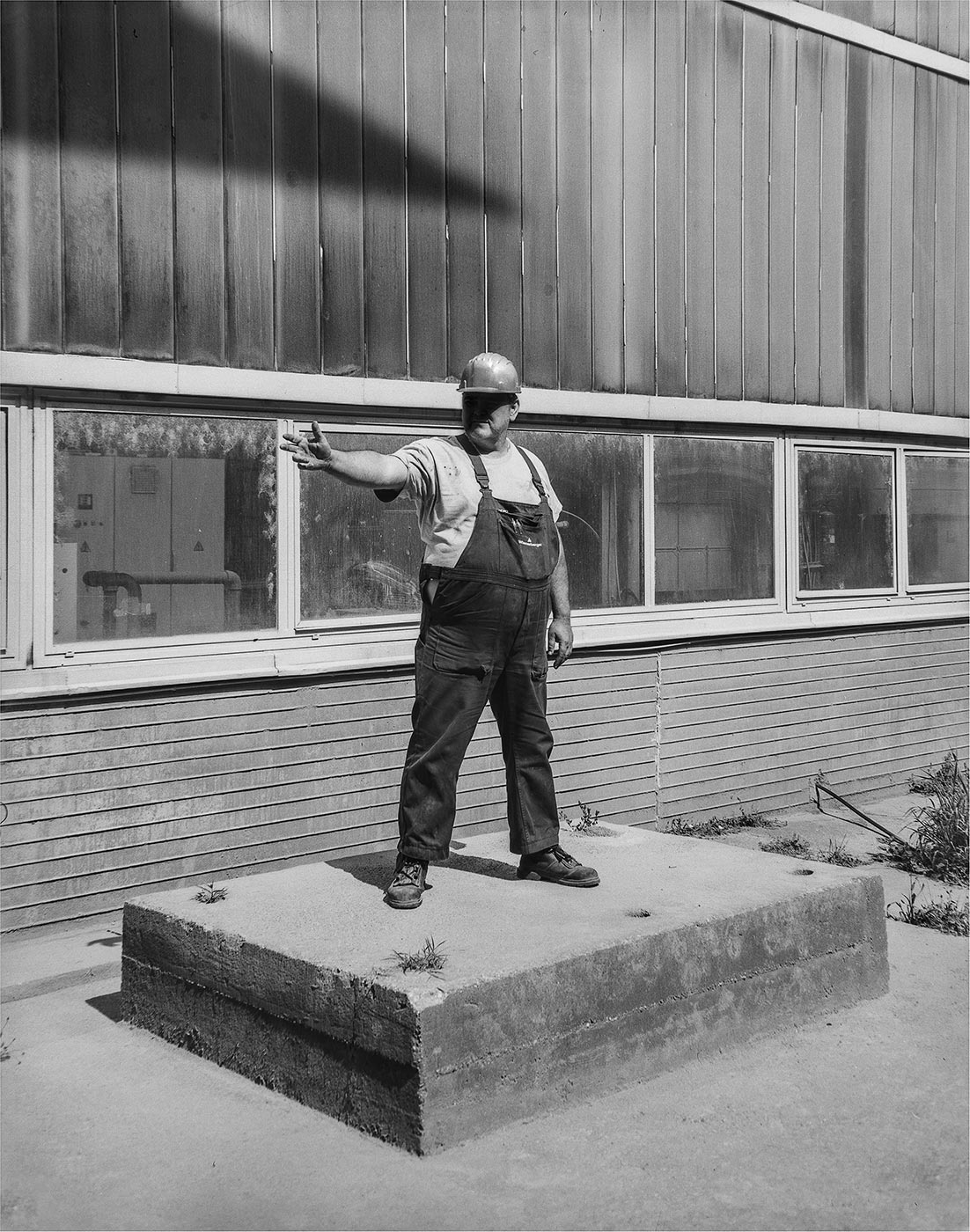

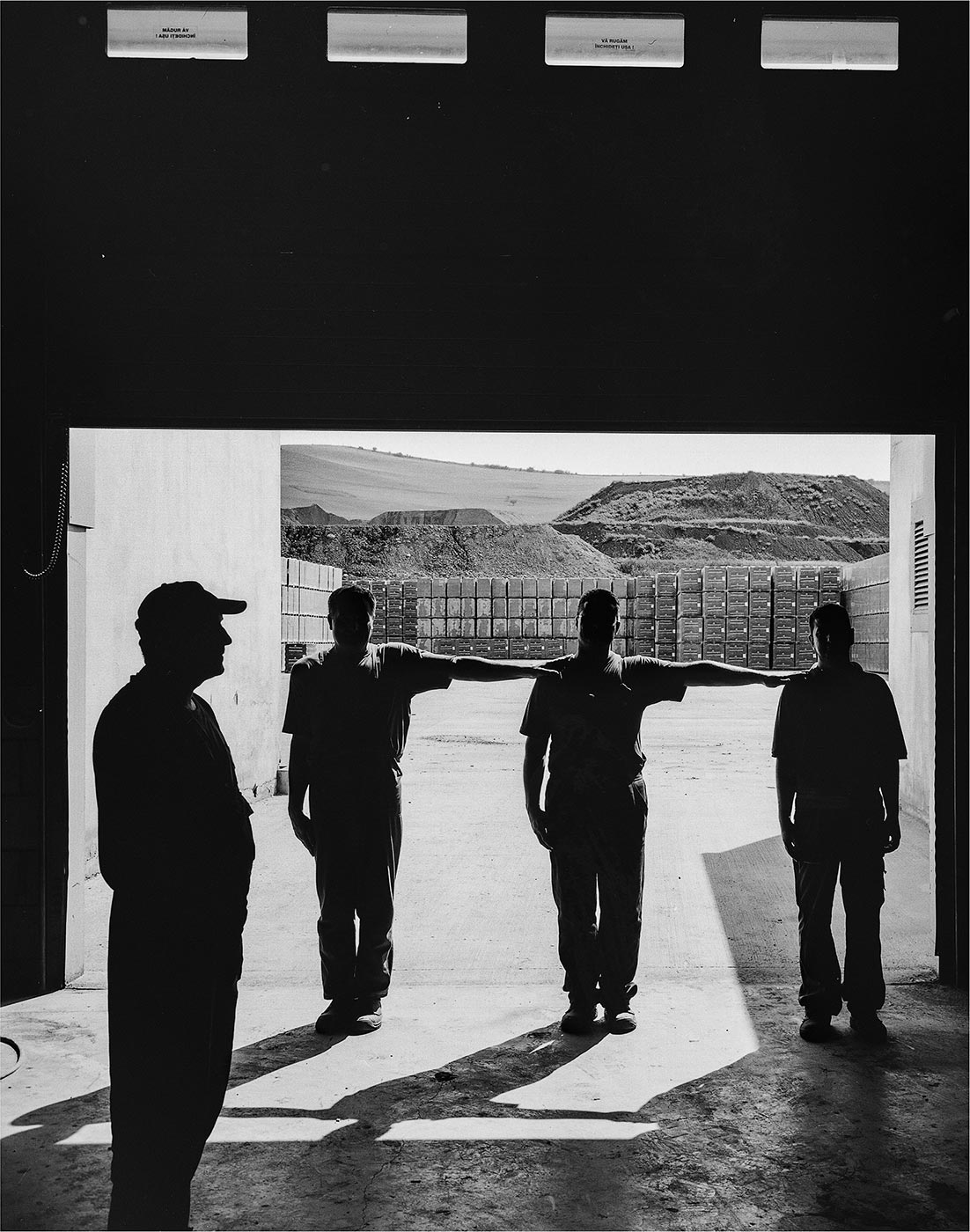

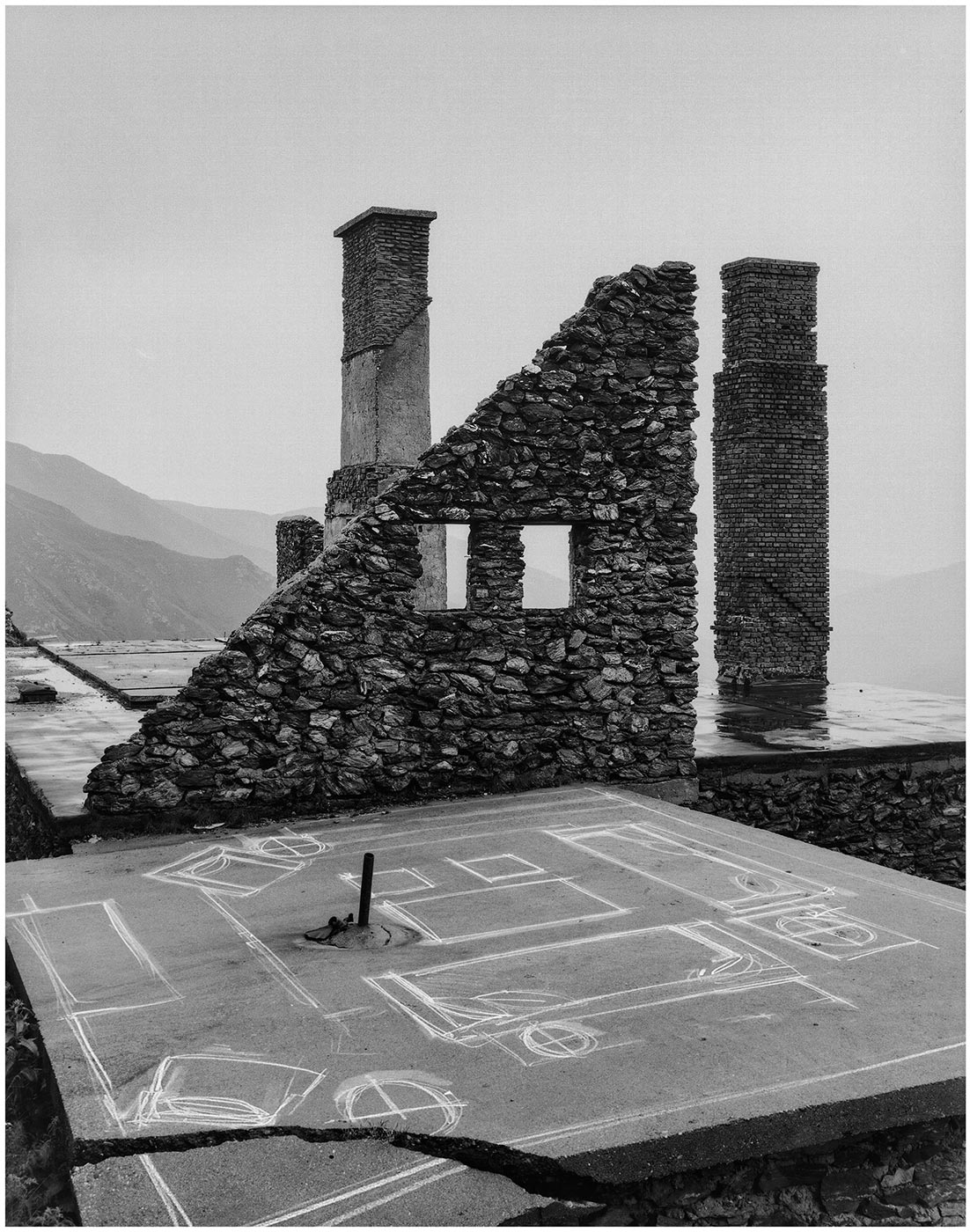

Human scale is defined by the horizon drawn around us by the outermost limits of our senses, but most of what we know of the universe reached us via technology. Over the past two years I tried to investigate the brick as the first step that mankind took towards delegating its evolution to technology. For this project, I restricted myself to working in the barren industrial environment at a number of Eastern-European brick factories in Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria.

How did you start thinking of the brick as a metaphor for the human being, and what do you think bricks and men have in common?

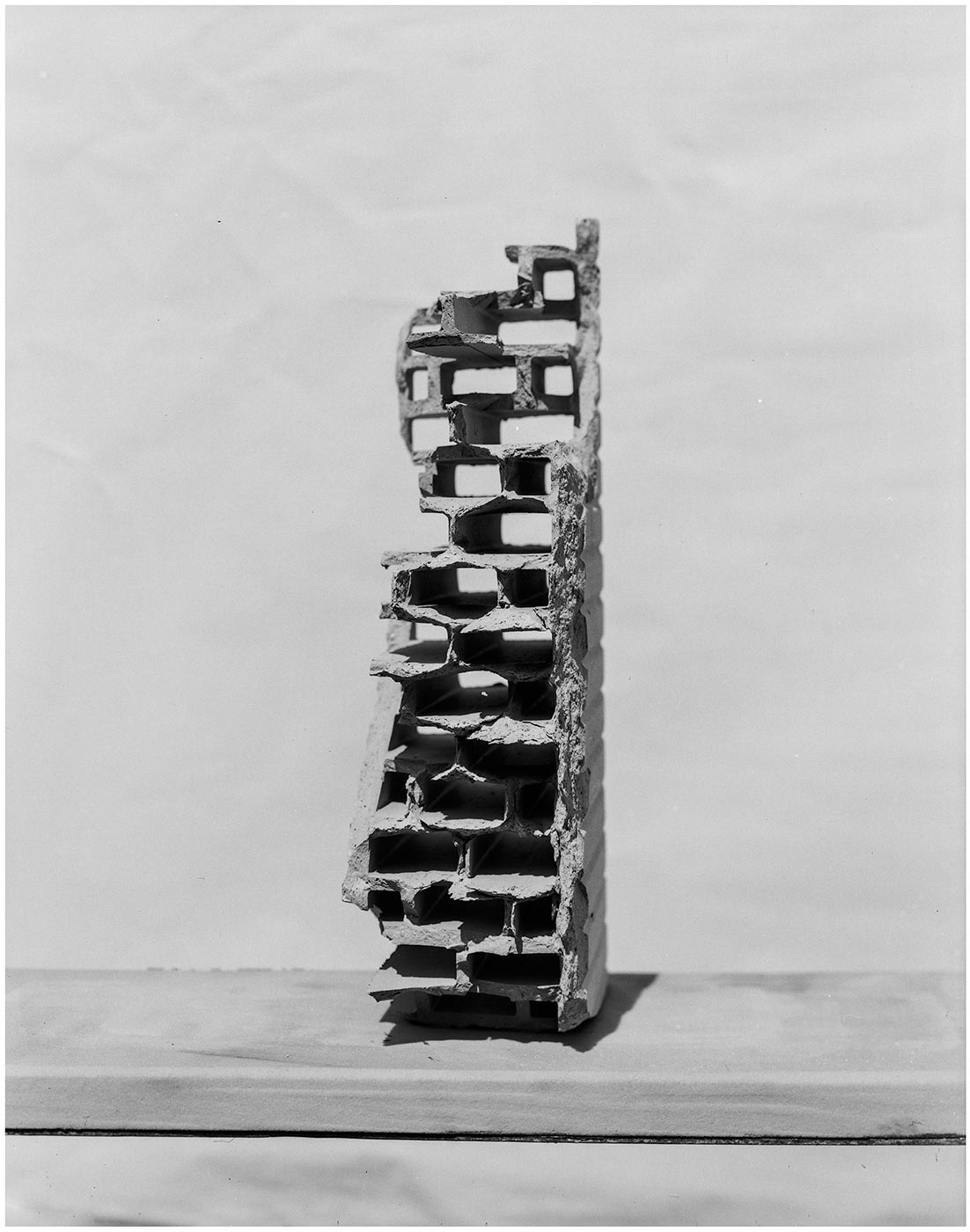

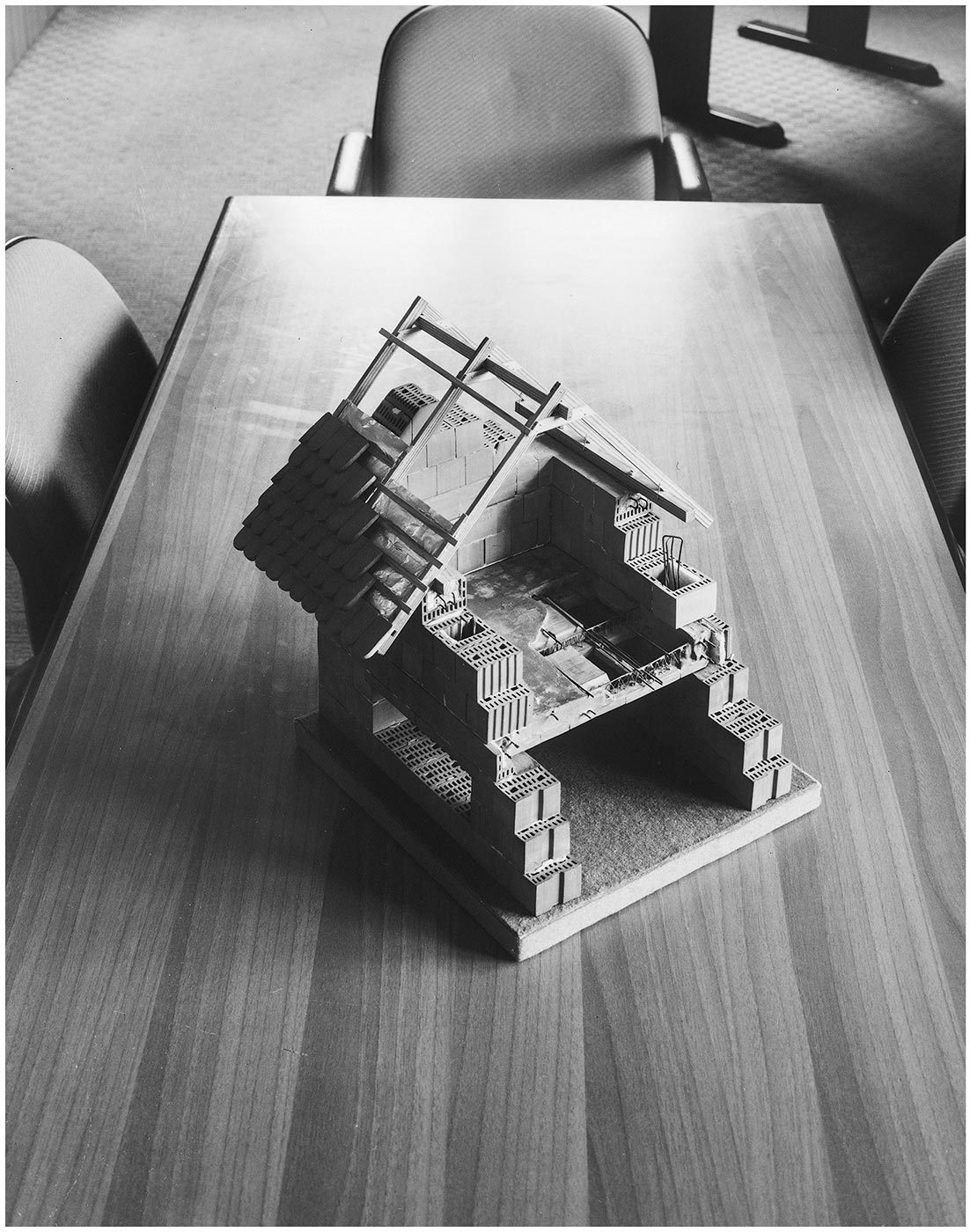

It’s more precise to say that in Human the brick is a metaphor for the human scale. Early into the work I saw an illustration of the proportional correlation between a schematic brick and the human hand. The brick was invented in a time and region – some 10,000 years ago, in Syria – when and where mathematics also emerged. The weight and proportions of these building blocks were originally derived from the measurements of the human body. So in a way, a brick can be considered an endlessly simplified code for what it is to be human; but the brick has also changed the way we think, it taught us how space can be rationed and formed into identical units, and how it can be used and understood in such a way.

I believe the first brick marked the point in evolution where biology invented technology, and started the process of converting the achievements of biological evolution into a technological one. We still experience this transition. The brick – a once omnipresent building block of our constructions – is now seen slowly retreating into obscurity. The timeline overlap between biology and technology is the era of human culture.

To create this series you’ve spent time in brick factories and discussed the project with the workers. How did that go exactly?

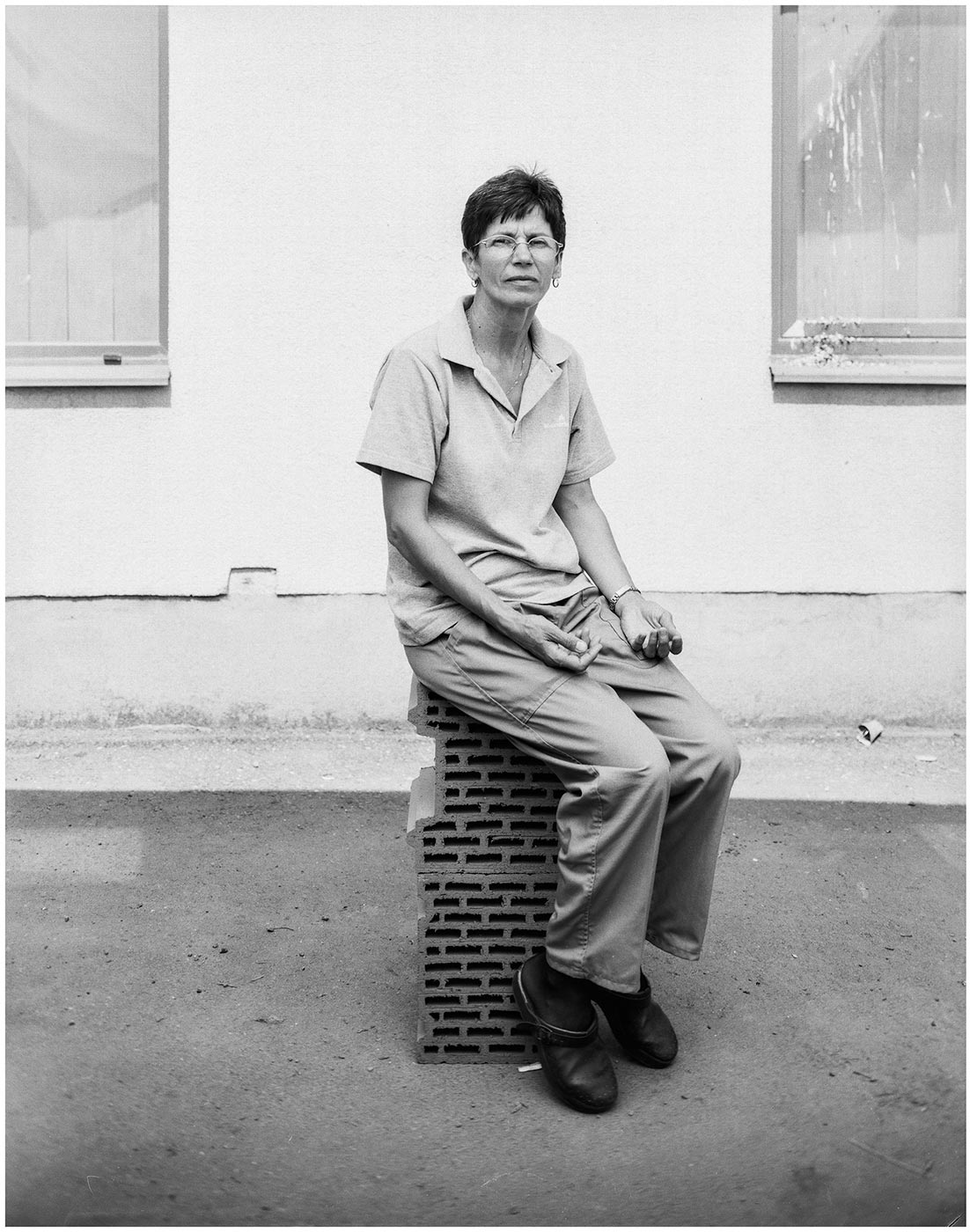

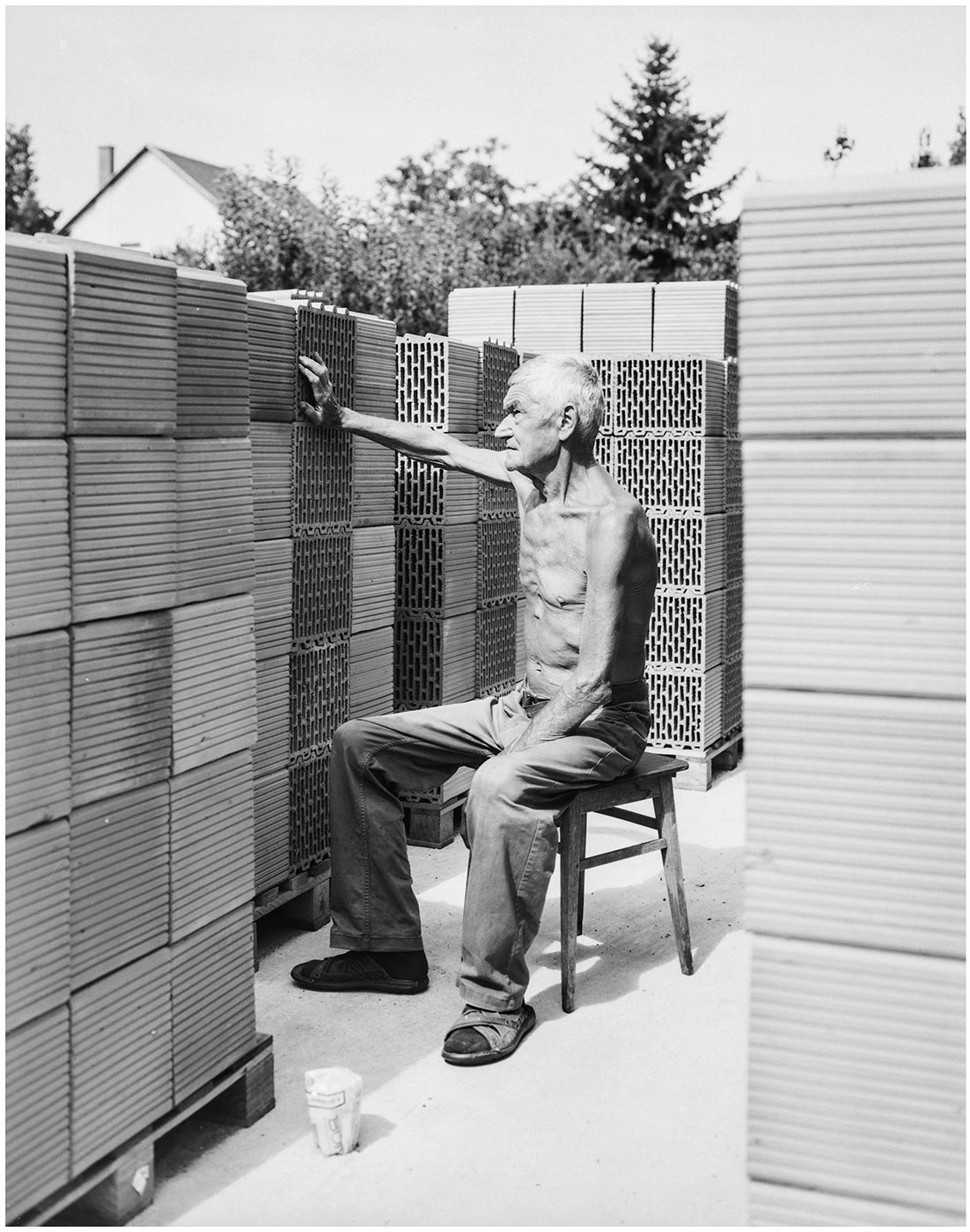

It came quite naturally. I knew from the very beginning that I wanted to photograph the workers. We talked about all sorts of things while I was being guided through the facilities. I took notes of what they were saying and tried to figure out a method of visualizing it. It was shocking to discover how little the workers contemplate on the nature of their profession, how monotonous and empty their job has become for them. It appeared to me that my role was to increase their awareness of the philosophical aspects of their rather mundane business.

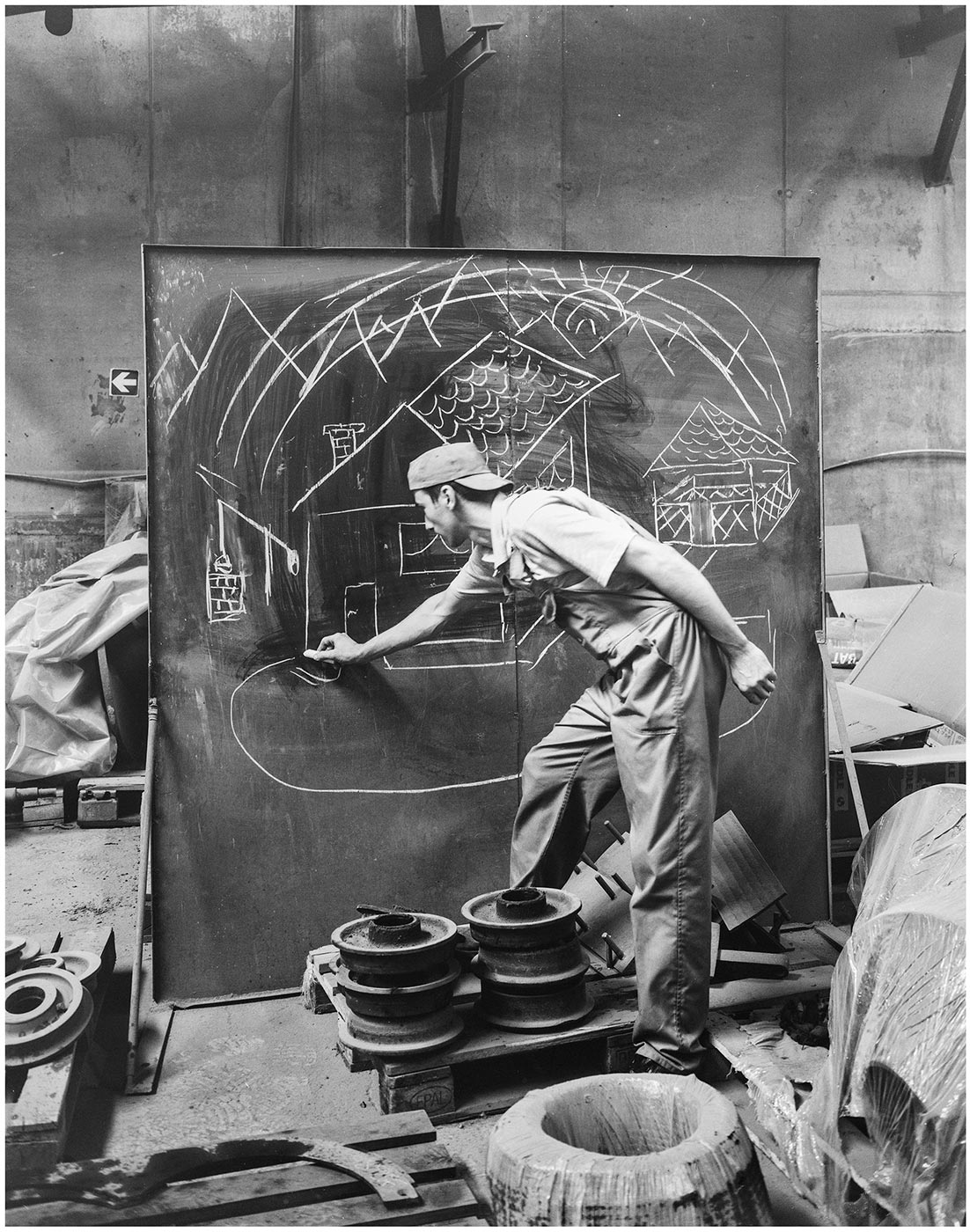

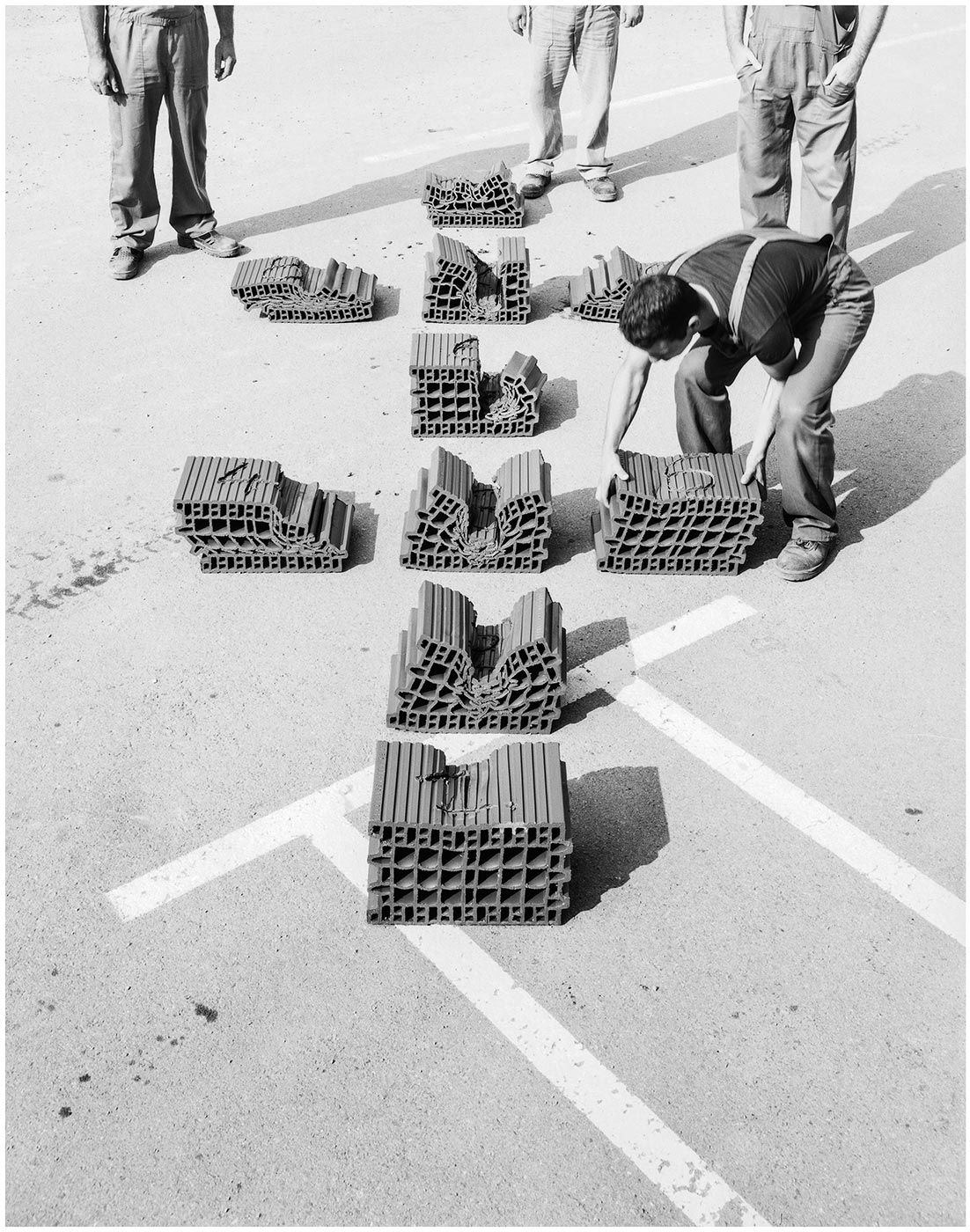

I prepared some experiments we called “responsibility practices” in which the workers were asked to perform a task – mostly drawing exercises and physical stamina tests – in front of their colleagues. They were offered room to express their dreams and fears: those experiments were probably the only time they enjoyed such freedom, and I was interested to see an individual act on his own instead of acting like a cog in the machine.

My first encounter was Otto, who works six days a week in three shifts. His dreams are haunted by bricks, but in the twenty years he has worked in the factory, he insists, he never thought of what he would build for himself from one day worth of bricks. Is it important for a worker to imagine how his or her dreamhouse would look like? Can we visualize how the individual feels about being a brick in a wall? A lady from the office – who does the accounting of massive amounts of products on a daily basis – admitted she had never lifted a single brick before; I made her do it. It was all very simple and intuitive.

Can you talk a bit about Human from a strictly photographic point of view? What kind of images were you looking for?

So many great projects suffer from being done so well that there’s no room left for questions. A choir singing in unison seems all too direct and plain – I prefer cacophonous instruments fighting for attention.

There is an unexplainable and almost touching honesty about the purely utilitarian image: it’s clear about its target, rarely attempts to appear sophisticated, is unaware of photographic styles and lacks artistic considerations. Because I didn’t know exactly what I was going to end up with when I started working on Human, I wanted some degree of flexibility for my project. But since I was using a 4×5 camera, I wasn’t just taking snapshots; so I took the liberty to intervene on the images in different ways, like scratching the negatives, rephotographing them or digitally adding some drawings at a later moment.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on this series?

My strongest influence was my own photographic practice which I abandoned in 2010, after a family tragedy derailed me into a visually and emotionally unmapped territory. With Human, I had the chance to return to and revision my earlier work.

I have worked on this series for more than two years, and during this time many artists and thinkers spoke to me a lot. I’m heavily influenced by the lectures and books of three excellent educators: Jacob Bronowski, George Kepes and Richard Dawkins. At one point Kepes’ vision felt so similar to mine I almost gave up continuing the work. From the realm of photography, Michael Schmidt, and of course Evidence by Sultan and Mandel.

What do you hope the viewers think seeing the photographs of Human?

Here’s a story that might explain why I better not answer this question. A couple of years ago – in 2012, I think – I presented my then most recent series, Waste Union, at the Fotomuseum Winterthur Plat(t)form. It consisted of about one hundred prints in two portfolio boxes. I explained the reviewers that the work pointed out how trash in landfills has become an aesthetic reference in the European landscape, as is visible in the colorful style of new neighborhoods; and how the hopeful utopia of a culturally diverse Europe is gone, etc. When I was done talking, one of them – an American artist – suddenly got upset and lamented that the pictures were not about that at all. They were about something else. I was caught off-guard and immediately replied with a question: “Then tell me what they are about?” The things I had just told were the things I had in mind while taking the Waste Union pictures. But she didn’t give me an answer, and I was left with the feeling of being caught lying. I was naive to trust my pictures would speak my words. So my lesson of that day was, unless you are a marketing expert, you better not trust your work too much or you might end up with a knife in your back.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

I’d love to be as inventive as Onorato and Krebs, convincing as Jock Sturges, sharp as Tina Barney, committed as Rob Hornstra, smart as Taryn Simon and honest as Gábor Kerekes, who died last year.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Vernacular. Horizon. Reference.

Keep looking...

Theo Tajes Wins the Single Images Category of FotoRoomOPEN | foto forum Edition

Stefanie Minzenmay Wins the Series Category of FotoRoomOPEN | foto forum Edition

FotoFirst — Michael Dillow’s Photos Question the Idea of Florida as a Paradisiac Place

Private Companies Want to Mine Asteroids, and You Should Care About It (Photos by Ezio D’Agostino)

Karolina Gembara’s Photographs Symbolize the Discomfort of Living as an Expat

Robert Darch Responds to Brexit with New, Bleak Series The Island

Enter FotoRoomOPEN for a Chance of Being Represented by All-Female Photography Agency ACN