Jared Ragland Tributes Walker Percy’s “The MovieGoer”

American photographer Jared Ragland discusses Everything Is Going to Be Alright, an intriguing project inspired by Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer novel that uses both original photographs by Jared and images found on Google.

Hello Jared, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

My photographic and found-image work is rooted in my lifelong exposure to the landscapes, people, aesthetics, and storytelling traditions of the American South. My mother has always said I should’ve been a writer, and as an artist I find myself using many of the devices writers and poets use – things like narrative, allusion, metaphor, and rhythm. While not always adhering to conventional narrative structures, I often seek to build relationships between fragments of content, fashioning literary and art historical references from arbitrary sources and forming ad hoc metaphors through the combination of pictures.

Please introduce us to your project Everything Is Going To Be All Right.

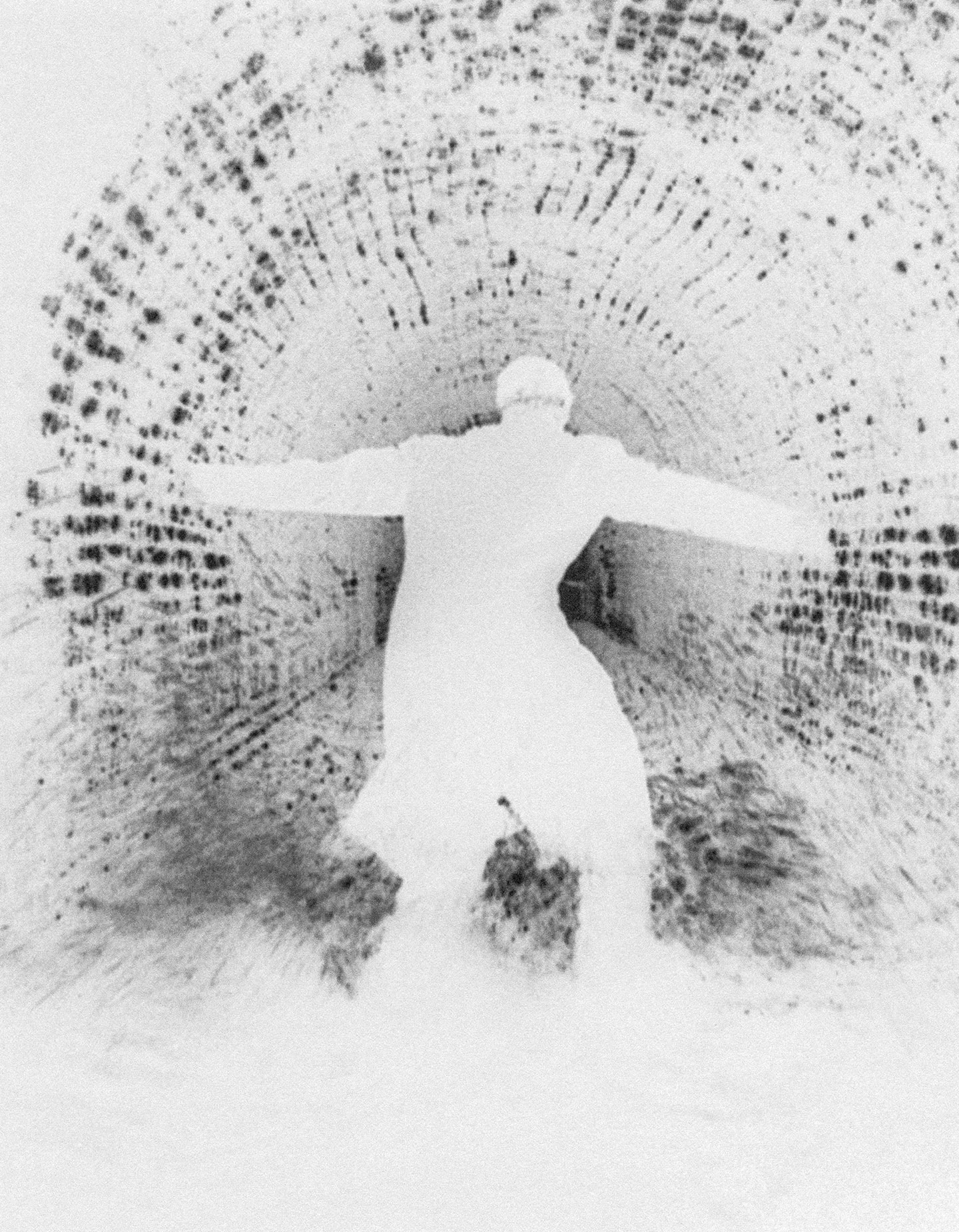

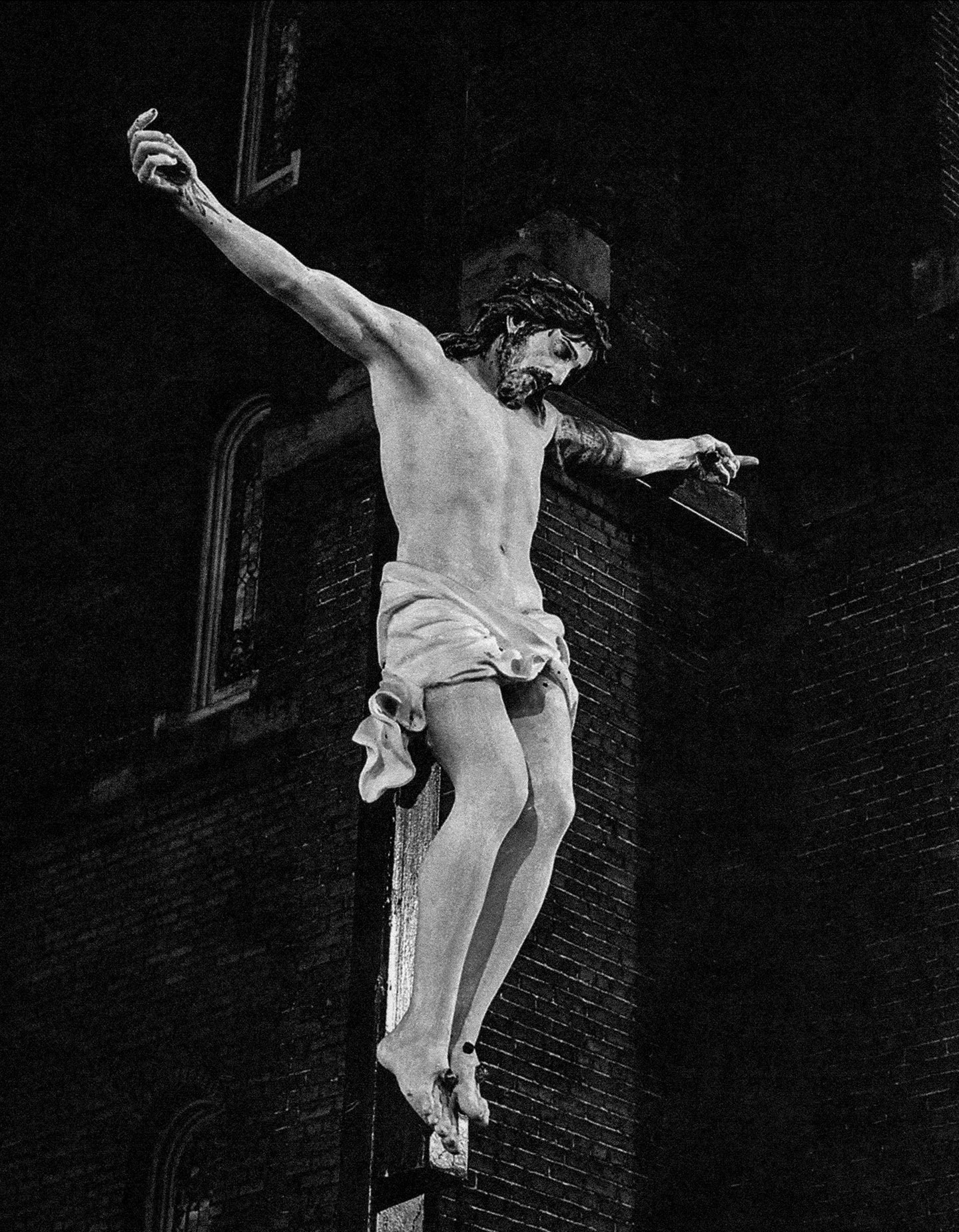

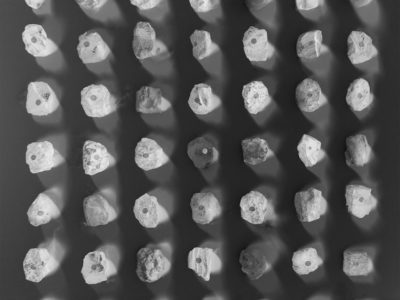

Everything Is Going To Be All Right uses a sequence of traditionally made black and white photographs as well as digitally sourced appropriated images to produce a meditation on Walker Percy’s 1961 novel, The Moviegoer. Made in New Orleans and largely shot at night, the photographs loosely document a dispossessed urban landscape, particularly the approximate locations of single screen movie theaters that once ubiquitously populated the city. After photographing these locations, I input the theaters’ names – ones like The Tiger, The Cortez, Dreamland, and The Gaiety – into Google Image Search to create a database of images that shares the landscape photographs’ melancholic tones.

Can you briefly describe what The Moviegoer is about for those who haven’t read it?

The novel tells the story of Binx Bolling, a thirty-something stockbroker in New Orleans who battles an existential crisis by going to the movies and embarking on “the search.” “The search is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life,” Percy writes. “To become aware of the possibility of the search is to be onto something. Not to be onto something is to be in despair.”

Why did you use a mix of original and appropriated photographs for Everything Is Going to Be All Right, and what type of images did you select?

The images in the series are connected, oftentimes tangentially, to the novel and to my own sense of “the search.” While the more familiar images may provide a point of entry, the context or combinations in which the original and appropriated images are presented reveal alternate, more nuanced meanings. Often fluctuating in feeling between intimacy and distance, private and public, realism and metaphor, the dualities in the pictures allow for a breadth of inquiry and mystery that, for me, is more exciting and challenging than a more straightforward, linear sequence of traditionally-made photographs.

What do you hope gets across to the viewers seeing Everything Is Going to Be All Right?

In The Moviegoer, it is the search itself, rather than arriving at some certainty, that compels Binx to act. Likewise, my goal is to encourage viewers to journey toward a kind of understanding based not only on observation, but also on self-reflection through contemplative analysis and deep viewing practices. By combining the two kinds of images – original and appropriated, the commonplace and the obscure – my aim is to dissolve boundaries of space, place, and time while building conceptual narratives that are held together by a consistent emotional sensibility.

Did you have any other specific references or sources of inspiration in mind besides The Moviegoer?

The project directly references Orson Welles in The Third Man, Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, ancient Egyptian funerary practices, Lon Cheney’s stage and film career, and the 1958 R&B hit Try Me (I Need You) by James Brown and the Furious Flames.

While making the project I experienced gut-wrenching heartbreak for the first time in my life. I also found inspiration in the concept of redemption, the resurrection of the dead, and the smell of sweet olive and jasmine on a summer’s night in New Orleans’ Garden District.

Musically, albums by Dustin O’Halloran, Dead Snares, Wooden Wand, and Tom Waits were on repeat during shooting and editing, and If I Could Be With You and St. James Infirmary by Louis Armstrong and John Scofield’s The Angel of Death were particularly relevant to the project’s themes.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Other people’s photographs, my career as a photo editor, books by Michael Ondaatje, and the sense of perpetual duty and guilt that comes by growing up in the Baptist church.

In the film Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus, southern writer Harry Crews said, “Stories was everything and everything was stories.” I believe this is absolutely true.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Many of my favorite contemporary artists are not necessarily “photographers,” but use photographs in their work. Artists like Christian Boltanski, Sophie Calle, John Stezaker, Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, Trevor Paglen, and filmmaker David Gatten each make work concerning different aspects of the contemporary condition while simultaneously commenting, and frequently critiquing, the photographic medium.

I’m always more interested in photographs that exceed simple depiction or description, and I am inspired by artists who, through means of presentation, installation, sequencing, appropriation, collage, etc., challenge the traditional means by which we read and understand pictures. Contemporary photographers who do it best are Ron Jude, Christian Patterson, Tim Davis, Jason Fulford, Raymond Meeks, Jason Lazarus, Justin James Reed, Gregory Halpern, Sam Falls, Amy Elkins, Daniel Shea, Sara Cwynar, Bertrand Fleuret, Shane Lavalette, Timothy Briner, Ben Alper, Zach Nader, AnnieLaurie Erickson, Jonathan Traviesa, McNair Evans – the list could go on.

I also love documentary-based work, and photographers Taryn Simon, Simon Norfolk, Antonin Kratochvil, James Nachtwey, Matt Black, Eliot Dudik, Jess Ingram, and Ivan Sigal have each had profound influence on my practice.

Lastly, I’ve had the great opportunity to share the classroom with some amazingly talented students. Aaron Canipe, William Knipscher, Nate Grann, Jordan Swartz, Sara Winston, and John Edmonds are former students who have begun strong careers as artists and publishers. They each have made me a better artist and teacher, and they continue to inspire me.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Symbol. Metaphor. Text.

Keep looking...

Theo Tajes Wins the Single Images Category of FotoRoomOPEN | foto forum Edition

Stefanie Minzenmay Wins the Series Category of FotoRoomOPEN | foto forum Edition

FotoFirst — Michael Dillow’s Photos Question the Idea of Florida as a Paradisiac Place

Private Companies Want to Mine Asteroids, and You Should Care About It (Photos by Ezio D’Agostino)

Karolina Gembara’s Photographs Symbolize the Discomfort of Living as an Expat

Robert Darch Responds to Brexit with New, Bleak Series The Island

Enter FotoRoomOPEN for a Chance of Being Represented by All-Female Photography Agency ACN