The Sand That Ate the Sea — Matthew Thorne Returns to the Australian Outback

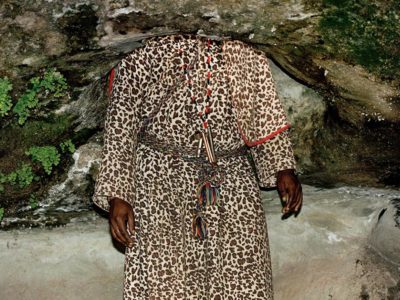

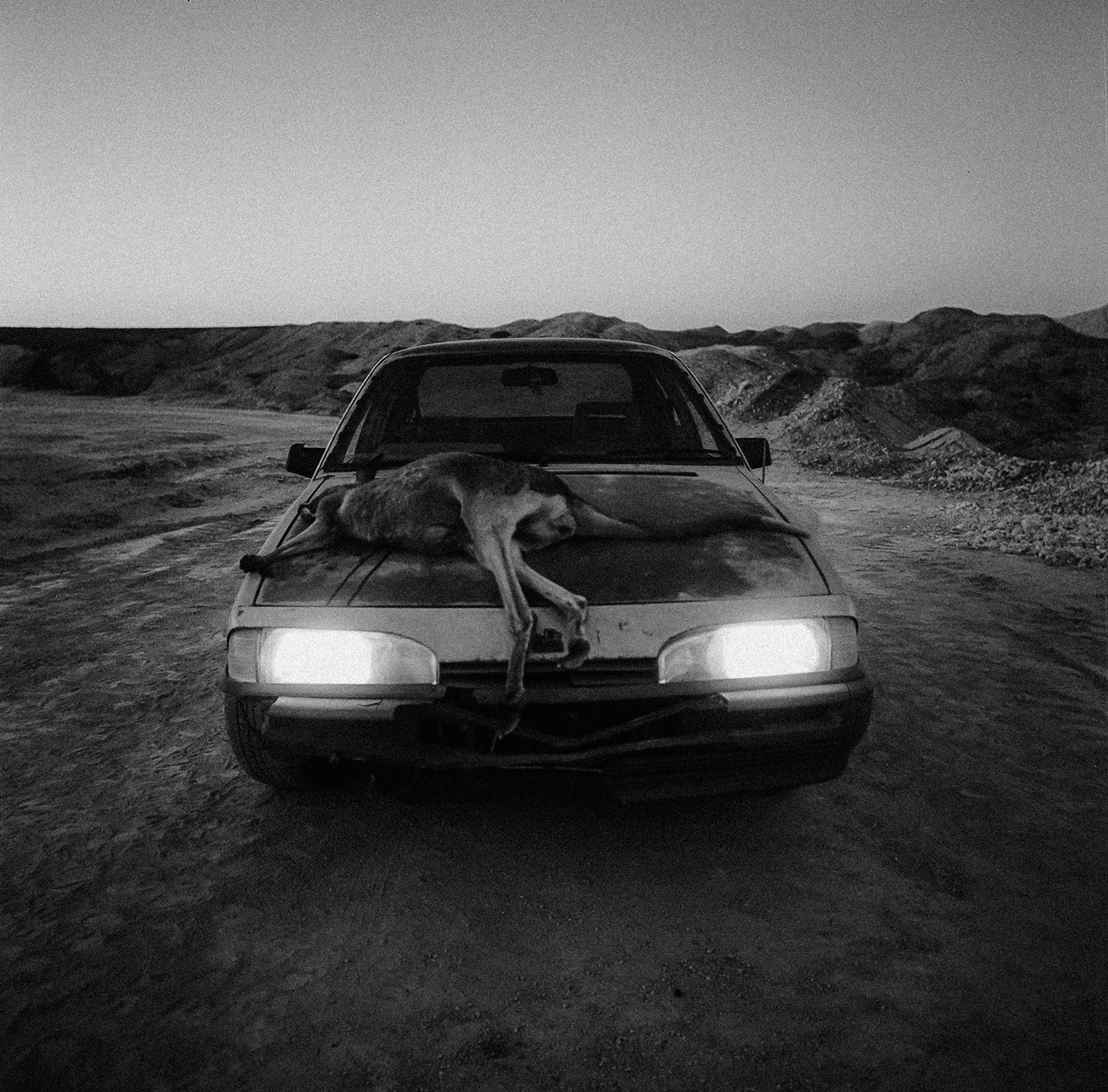

The Sand That Ate the Sea by 24 year-old Australian photographer Matthew Thorne started as a film project, but Matthew knew from the outset that “I wanted to shoot photos on the side. In a broad sense, the film and the photos were the culmination for me of what I felt about being Australian, and my goodbye to Australia as I planned to move overseas. It was a documentation of a red dirt that I knew from my childhood, and a series about what I always felt Australia was in my memory: a harsh land inhabited by people who might generally be a bit rough but have this great, honest working man’s wisdom. I think these aspects are lost in the current discourse around Australia, so I wanted to bring them back.”

For The Sand That Ate the Sea, Matthew spent six months in Andamooka, a small opal mining town in Southern Australia: “I think you have to earn your right to take photos in communities that you don’t belong to. I was lucky to have family in Andamooka that helped open the place up to me, but I knew that I didn’t want to come in for a weekend and leave. I wanted to be there for an extended period of time because there is a wisdom and a stillness there that I wanted to understand. The land is harsh but beautiful, and it felt to me to be very connected to my childhood and the land that had made me. I tried to be a part of the community as much as I could, to learn about its daily life and history before I could feel comfortable passing on the story, and carrying a chapter of that.”

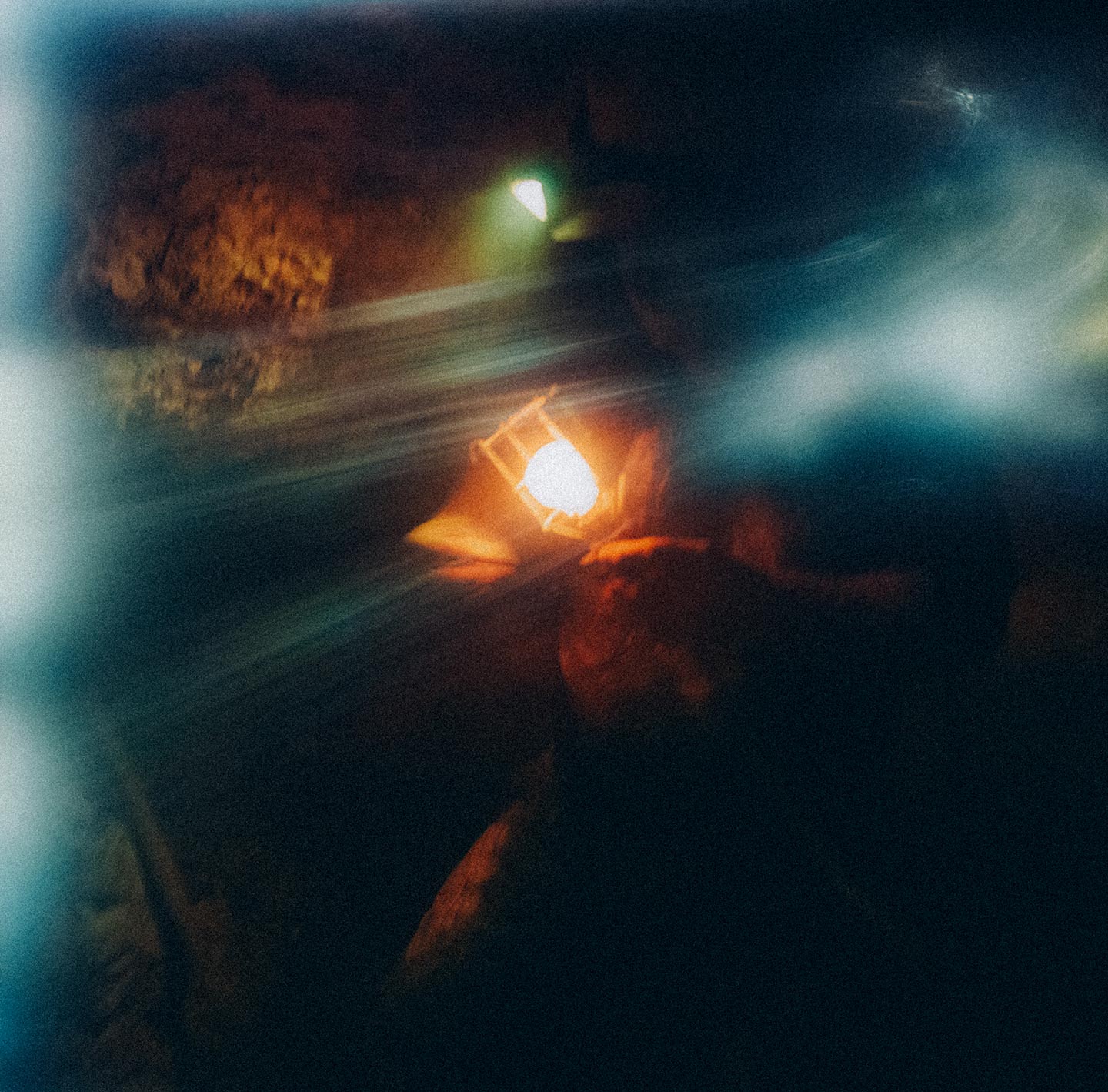

Except for three pictures taken on a digital camera, Matthew shot The Sand That Ate the Sea entirely on film: “I always knew I wanted to use film—there’s something about the heat of the desert and the harshness of the Australian sun that needs to be captured on film. And I knew I wanted the images to echo the feeling of the place: pragmatic and practical, mixed with mystic and ephemeral. I think there was also an embracing of intimacy even in moments that weren’t intimate (especially as Australians in general can be so publicly guarded). Moreover, I wanted to fall in love with the accidents of the camera and stock, and to embrace those mistakes and that ‘wrongness’. I believe the invitation of chance into work is important to finding some sense of realism as an echo of life.”

Matthew hopes that those who will see the images of The Sand That Ate the Sea feel something, “but I don’t mind so much what that is. Just that it says something to them, in their own personal truth. I do hope it resonates with Australians in particular though—we are a frontier nation, and we’ve lost our frontier. We’ve returned to cities and said goodbye to the Australia that was, and I think we need that. We need to return to it.”

Some of the references Matthew had in mind while working on The Sand That Ate the Sea include the work of Alejandro Jodorowsky (“maybe his philosophy and ideas more than his film-making“), the “unabashed Australianism” of photographer Tracy Moffat, and photojournalist Don McCullin’s attitude to “subject, presence and observation.” He also thought of the words of advice he received by fellow photographer Joan Tomás: “‘You’ve got to be close. You’ve got to get closer, to be intimate. Don’t be so distant.’ I think the challenge to be honest to that—to Joan’s wisdom—was important to me.”

Matthew’s main interest as a photographer is “our relationship to time, and the documentation of that. We have a finite mortality, and that defines everything. The body is a time machine, it exists and categorizes time as it moves through life; when the body ends, so does the movement of time. I think there is something interesting in that: who we come to be at a specific moment in time (as individuals as well as a society) and how we come to be there at that moment. I’m also interested in how the land changes us—how we are all born as similar creatures, but we are made different by the place we grow up in. I think for me photography is about bearing witness. It’s the presence and the observation of a moment that is most important, and how—strangely enough—photography too then becomes a time machine, able to steal a moment from time, and make it holy and endless.”

Cinema and photojournalism are the main influences on Matthew’s photography: “I think the image as a marker of time is something that cinema (in its great works) can begin to grasp; how that plays into still images is for me the magic.” For a list of artists in particular who have been of inspiration, he mentions Immants Tillers, Satoshi Kon, Koreeda Hirokazu, Bill Henson, Max Dupain, Richard Mosse, Françios Joseph-Heim, Rothko, Tim Winton, Peter Greenaway, Carol Jerrems, J.W. Waterhouse and Joel Meyerowitz. The last photobook he bought was Lux et Nox by Bill Henson.

Matthew’s #threewordsforphotography are:

Time. Relationship. Mortality.

Keep looking...

Inside the Spider — Suzie Howell Captures the Beauty (and Waste) of East London’s Marshes

Lewis Brillet Reflects on His Experiences of Home and Family After the Death of His Brother

Julia Morozova Wins the 3-Month Mentorship Offered by Wren Agency for #FotoRoomOPEN

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2019

Jason Koxvold’s Photobook ‘Calle Tredici Martiri’ Was Inspired by His Grandfather’s World War II Diaries

Valentina Casalini Explores QT8, a Once Futuristic, Now Declining District in the North of Milan

Mark Griffiths Photographs the Wild Swimmers of the U.K.