FotoFirst — Bucolic Photos of the Small Italian Town Where Massao Mascaro Found His Family’s Roots

Massao Mascaro is one of the talented photographers who have exhibited their work at gallery Espace Jörg Brockmann, the juror of the current #FotoRoomOPEN edition (submit your work before next 15 May 2019 for a chance to have a solo exhibition at the gallery!).

This interview to French photographer Massao Mascaro was originally published on 25 April 2016.

Hello Massao, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I like to use photography as a tool to create a dialog with life on a daily basis. Photography is my way to cope with the many questions I ask myself, to give them substance and try to find an answer.

Please introduce us to Ramo.

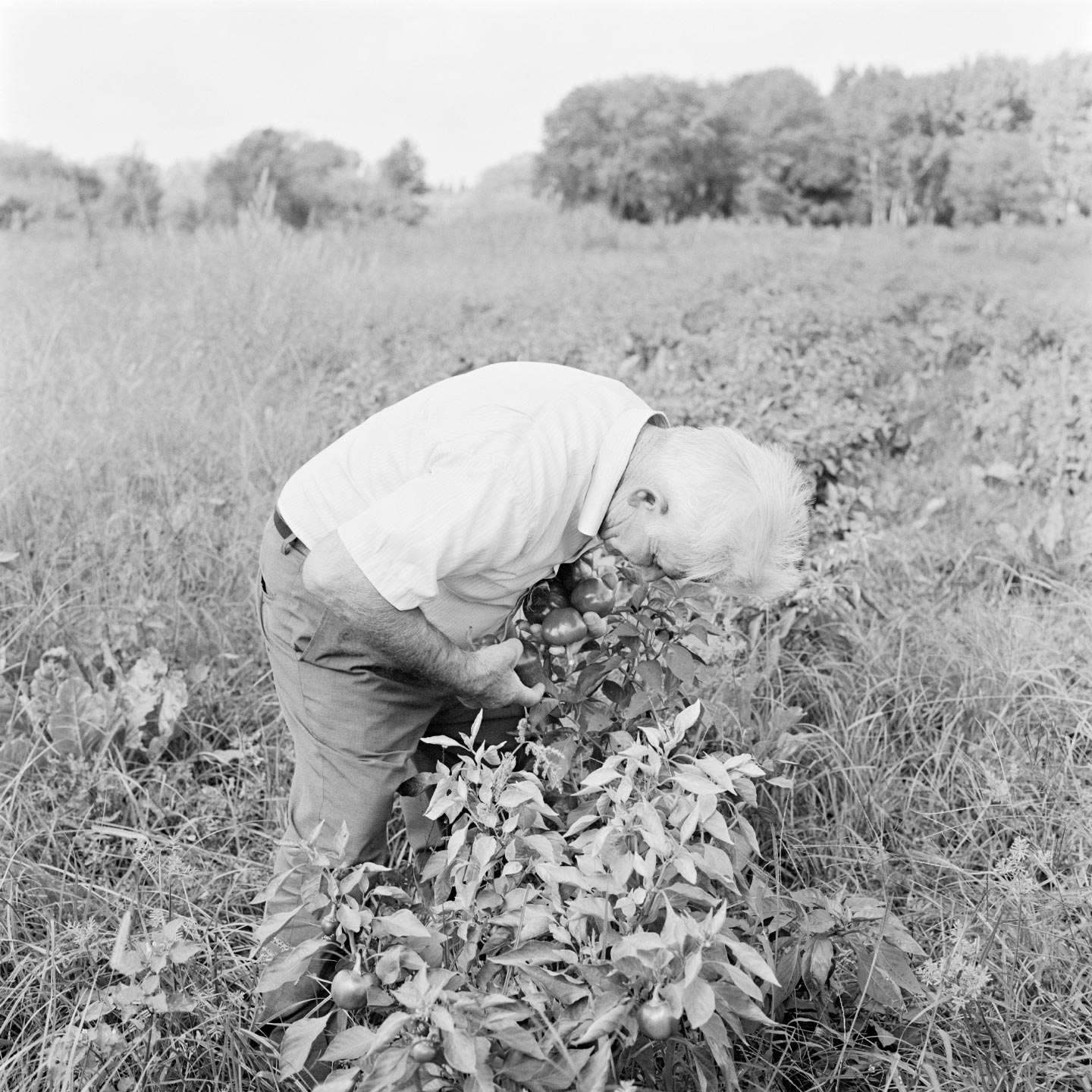

I started by photographing my grandfather’s vegetable garden. He immigrated to the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region in the north of France from southern Italy. His garden looks like a clutter of colorful plants that are quite unusual for the region. But with Ramo I had no intentions of making aesthetically interesting images; instead, my goal was to answer the question “Where do we come from?”. My grandmother told me the story of how she and my grandfather left from Calabria, the region in South Italy where they are originally from, and finally arrived at Lens, France. So my initial idea was to take the reverse journey, from the North of France to southern Italy; to better understand our family’s history by retracing it.

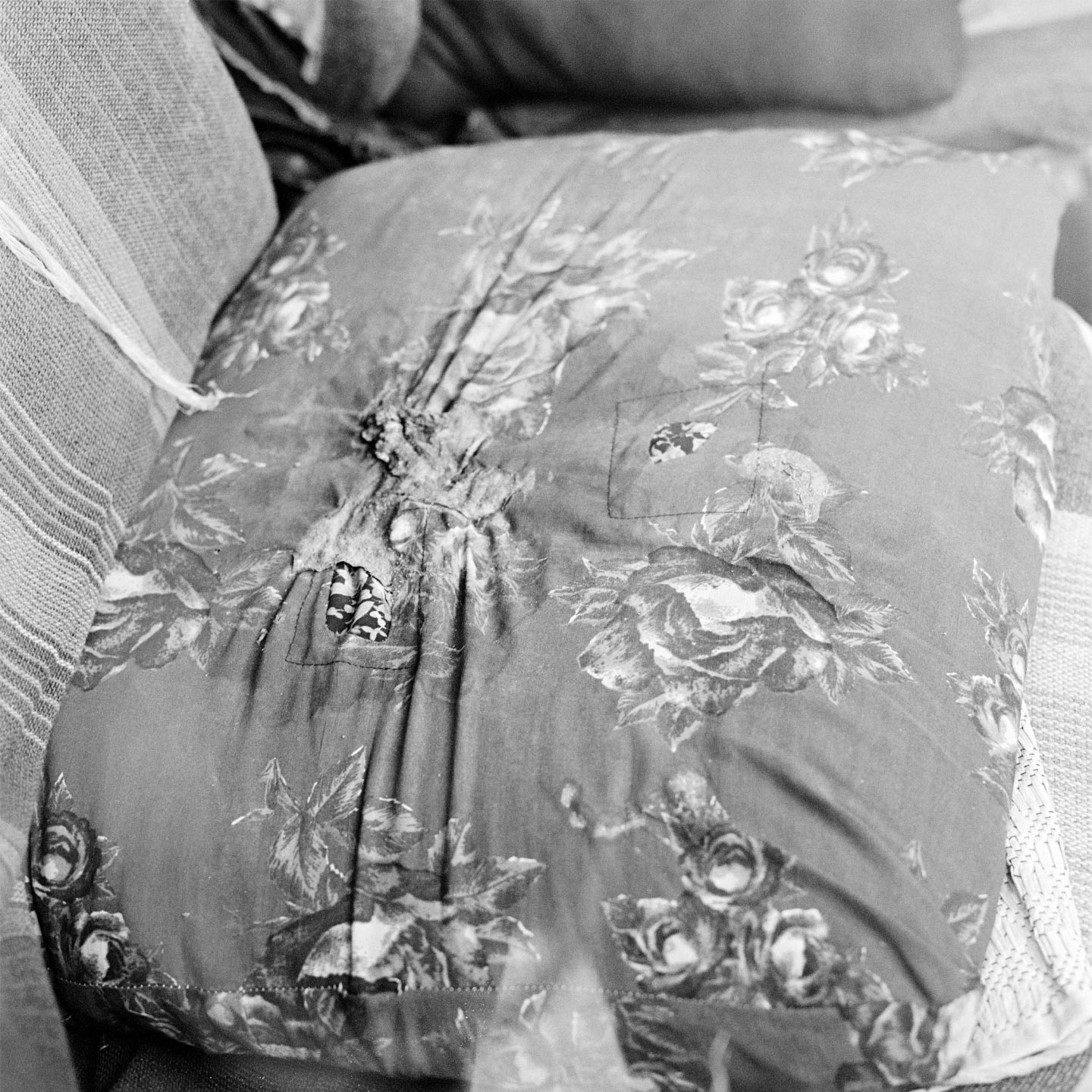

I was raised in a big Italian family. The house of my grandparents – i nonni – was where we would all gather. For twenty years we’ve had meals around a table covered with a flowery cloth; twenty years of eating pastasciutta and playing scopa… Ramo is a tribute to this legendary pasta dish and this game of cards, typical of Naples.

Where exactly were the images of Ramo taken?

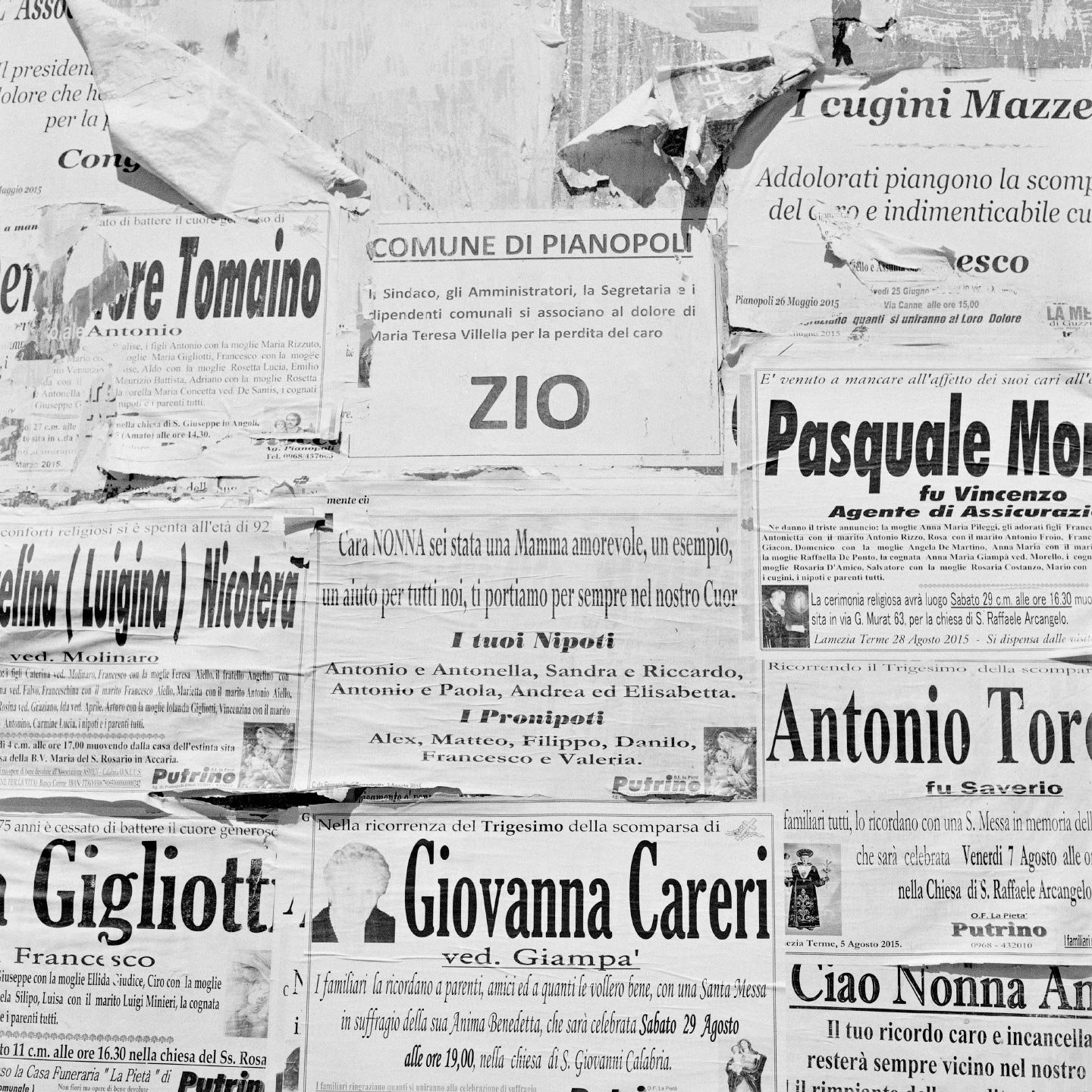

All the images were made in Calabria, and more precisely in the proximities of Pianopoli, the small town where my grandparents come from. I took long walks across the countryside, I spent time with the locals, chatting with them or simply watching them work the land (sometimes I also helped a bit…). Due to a fragile economy, these people can’t afford expensive machinery, so they use archaic techniques and their hands as the main tool. The more I explored the area the more I became familiar with it, so I was able to avoid cliche images and to focus my approach on the metaphor of labor. I tried to represent the attachment to the land by photographing the living plants – the vegetation, the trees, the branches. During my stays I myself have become fond of certain trees.

How would you describe your approach to photography?

I often start a new series from a naively general question like “Where am I from?”, “What is nature?”, etc. These reflections trigger a state of curiosity that orients my research on the subject matter. I first turn to photographic works, literature, cinema, sciences, etc. Then I start taking pictures. Through framing I isolate a part of the visible world, and later I put it in relation to other pictures. I like the idea that the work originates from a question and leads not to one unique answer, but to a series of fragments of space and time… Time plays a major role in my photographic practice, both in regards with my creative process – a significant span of time passes between the moment I take a photograph and the moment I look at it – and my way of telling stories: be it on the web, on a wall or in a book, putting several images together on the same, bi-dimensional support equals to creating a piece of space-time… The act of photographing implies the latent idea of creating a different time, a subjective memory. Milan Kundera wrote in Slowness: “giving duration to a form is a demand of beauty as well as memory”.

What kind of images you intended to make for Ramo in particualr, and how do they fit the project?

I took most of the pictures during the summer or the fall to emphasize the role of light. Light is essential, for plants like for photography. In Calabria, vegetation is quite chaotic and prolific, it sprouts up and grows everywhere. The book dummy ends with two images of a Barbary fig, of which one has no fruits, the other does. This illustrates well such abundance of vegetation: the Barbary fig can grow in any spot that is reached by light, and gives its fruits generously. This is also true for immigration: no matter where you go, if there is light, you can settle down, live and give life.

The book’s rhythm is created through a series of pictures of this vegetal chaos that I loved to be in. There’s also an articulation of images of fragments that reference several elements: the archaism of working the land, the precariousness of living in a small village, the symbols of a system of beliefs situated between the earth and the sky. Although there are no portraits in the sequence, the human presence is evoked by the gestures, the bodies of the children, the grown-ups or the grandfather.

Is there anything in particular you’re trying to communicate through Ramo?

I think it’s important to point out that Ramo is my first photographic series. As I worked on this project, at the same time I was fulfilling my desire to become a photographer. It took me some time to understand what I was about to do. Now I realize that besides constructing the series I was also developing the first elements of my photographic language. For Ramo I’ve always used black and white and the square format – since I was just starting out, I needed a rigid structure, and that seemed the best solution. In fact my decision turned out to be more difficult than I thought: the square format is a real brain-teaser. It dictates a frontal approach to the subject that I wanted to overcome to make more complex images.

I see the sum of all the trips I took like a journey in search of myself. Working on Ramo helped me understand, accept and affirm a part of my identity (that I often maintain by having some pastasciutta). With this project I aimed at investigating our attachment to life, and what I found is infinitely bigger than what I was looking for. Starting from the history of a family, Ramo came to be a simple reflection on the relationship between men and nature.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Ramo?

The making of Ramo has been closely followed from the start by a friend photographer, Hugues de Wurstemberger. He teaches at Le 75 school of photography in Bruxelles, where I studied from 2010 to 2013. I identify a lot with his works, like his series about farmers or the one about children. In the final stages of the work, Federico Clavarino, who teaches at the BlankPaper school in Madrid, has showed me some keys on how to start and end a book… an essential piece of advice. His photobook Italia o Italia has deeply impressed me.

Finally, I was very influenced, although more indirectly, by the novels of Italian writer Erri de Luca. Half a worker half a theologist, half a mountain dweller half a novelist, De Luca’s books are characterized by a simple narrative yet richly poetic. Plus he’s from Naples, and he writes about the southern Italy that he left… his biography resonates with me.

How do you hope viewers will react to Ramo?

First and foremost, Ramo is an honest tribute to the my family’s origins. As a child you don’t ask yourself certain questions, then one day you start wondering “Why are we the only ones eating pastasciutta and playing scopa?”. Moreover, I hope the whole set of images communicates this idea of attachment to life.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

I spend a lot of my time admiring and trying to understand the works of Lee Friedlander, Paul Strand, Walker Evans and Josef Koudelka. I was equally influenced by cinema, and in particular films like Abbas Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees. Recently I’ve been watching the films of Mexican director Carlos Reygadas, like Silent Night or Japón. I find them fantastic.

Another important factor is that I work with a collective, La Grotte. We engage in a strong series of activities revolving around photography. Soon we will release a collaborative project called Speaking in Tongues.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Paul Graham, John Gossage, Stephen Gill, Issei Suda, Jochen Lempert, Raymond Meeks, Ricardo Cases, Guido Guidi, Michael Schmith, Federico Clavarino, Michel Vanden Eeckhoudt, Alec Soth, Christian Patterson, Gerry Johansson, Ron Jude, Miguel Ángel Tornero, Mark Steinmetz, and many others.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Imagination. Memory. Fragments.

Keep looking...

42 Wayne — Jillian Freyer Has Her Mother and Sisters Perform for the Camera

Catherine Hyland Captures the Touristification of China’s Barren Natural Landscapes

Ten Female Photographers You Should Know — 2020 Edition

FotoFirst — In Love and Anguish, Kristina Borinskaya Looks for the True Meaning of Love

Vincent Desailly’s Photobook The Trap Shows the Communities in Atlanta Where Trap Music Was Born

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2020

Louis Heilbronn Uses Portraits, Theatrical Images and Drawings to Explore How a Myth Is Created