Federico Clavarino Connects with His Grandparents’ Past as Ambassadors of the British Empire

Federico Clavarino is one of the talented photographers who have exhibited their work at gallery Espace Jörg Brockmann, the juror of the current #FotoRoomOPEN edition (submit your work before next 15 May 2019 for a chance to have a solo exhibition at the gallery!).

This interview to Italian photographer Federico Clavarino was originally published last 9 November 2017.

Hello Federico, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

This is not an easy question. I guess that what interests me changes over time, but there might be some kind of underground current, something I can’t quite get hold of but that someone else might grasp better than me when looking at my work as a whole. Generally speaking, I am fascinated by history, maybe because of my family. Both of my parents studied history, and my aunt is a historian. I am also troubled by power, and by the guises it takes on, the different shapes it inhabits. I like to photograph objects, to feel their volume, to question their nature, to guess at the intentions that lie behind their making, at the desires they might evoke. I am also interested in narrative, in ellipses, in the empty spaces between words, images, things. I am excited by the unpredictable associations that arise when two or more objects are brought together into the same place, be it a room or the page of a book. Finally, I enjoy walking a lot, and aimless wandering has always played a key role in the way I approach photography.

Please introduce us to the story of your grandparents that underlies Hereafter.

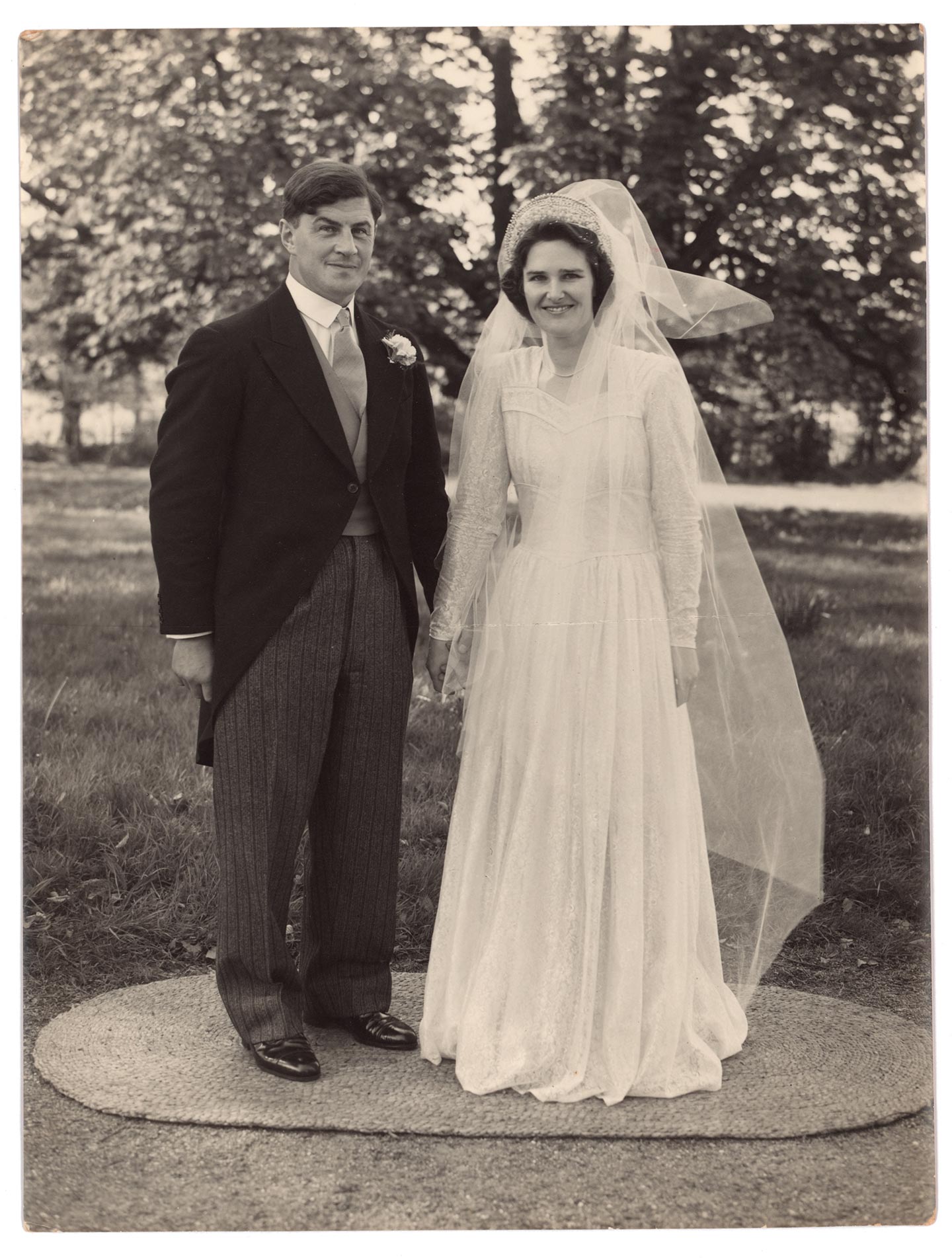

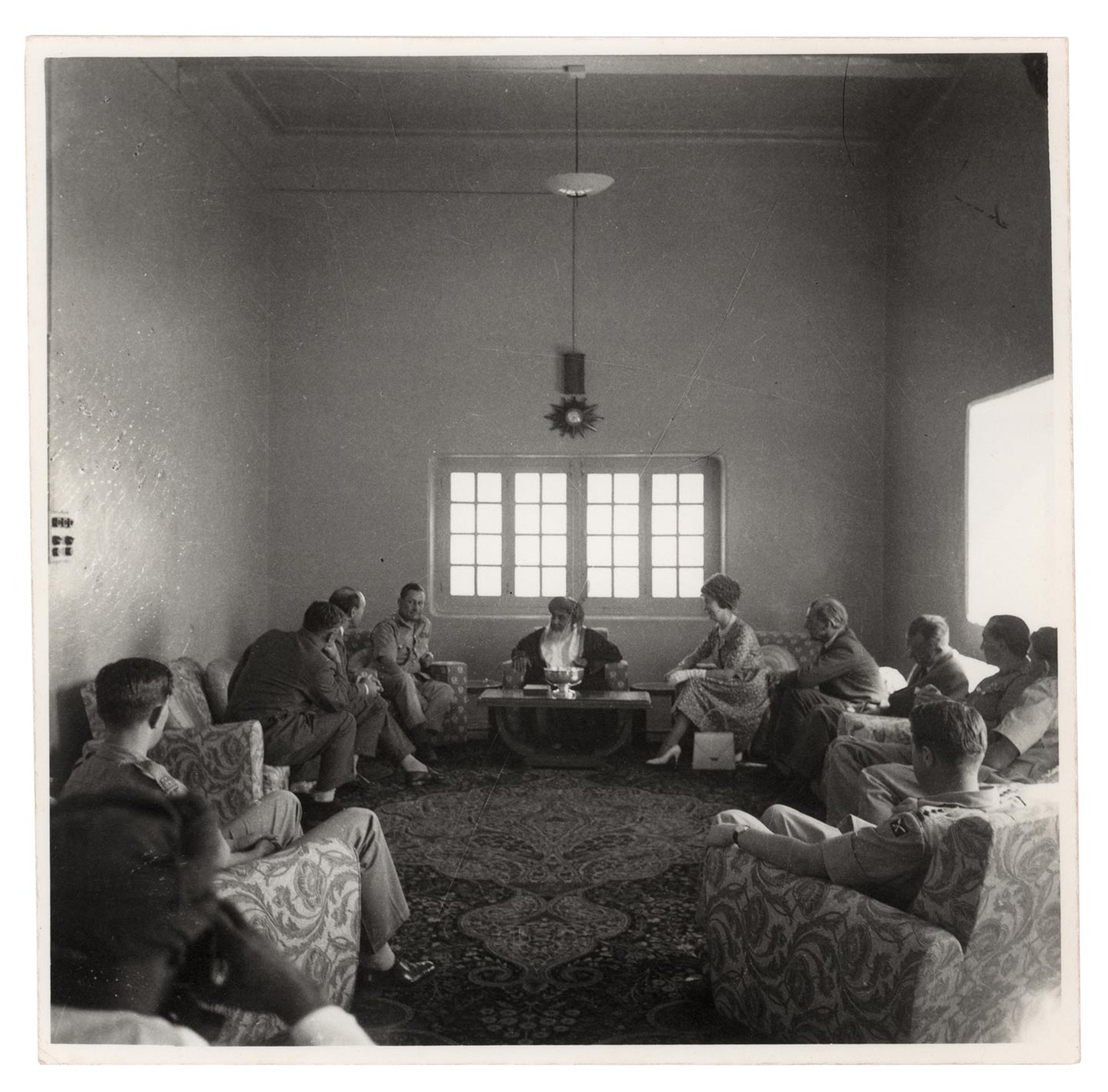

My grandparents spent around forty years living in east Africa and the Middle East. That was right after World War II. My grandfather had learnt Arabic while in prison in Germany, and he was sent to Sudan to be what they called a District Commissioner. At the time Sudan was still an Anglo-Egyptian condominium, which meant the British were in fact running the place. He met my grandmother on leave, she was a surgeon, and they both lived and worked in Sudan until its independence. My grandfather later joined the diplomatic corps and was posted to Libya, Oman, Jordan, Aden and Cyprus. He ended his career by returning to Sudan, this time as Ambassador. My grandmother had to quit her job. They moved back to England in the 1980s.

All of this is leads us to the other main component of the work, one that is less personal and maybe more political. My grandparents were raised in imperial Britain, and they fed on the literature, the imagery and the ideals which the colonial empire was founded on. My grandfather was born in India and his mother descended from General Gordon of Khartoum’s older brother, Henry Gordon, something he was always very proud of. Their lives and work in countries like Sudan or Jordan were driven by a sense of duty that was built on those foundations. All of the narrative they produced—the stories, the memoirs, even the photographs—are imbued with that ideology.

Many of you grandparents’ old letters and photos are included in Hereafter, but you’ve also traveled to and took photos yourself in the countries where they worked when they were young. How do your pictures fit in with the archival material you’ve put together?

I could have just brought together all of the material my grandparents produced to tell their story, or to dissect and analyze what was their world (the full historical weight of which is nowadays very relevant). In a way, this is what I did, by arranging part of the archive in a chorus of voices and images that convey a complex set of meanings by resonating together. But I felt I needed to somehow add my voice to the chorus—I felt I was part of the story and I wanted to go and see for myself, in spite of the limited understanding I might have of, let’s say, the situation of contemporary Sudan. What they saw and photographed is different from what I saw and photographed. Our intentions were different, but what they did influenced what I did, the same way as those countries are now different from those they lived in, but you can still feel the consequences of what the British did there.

How would you describe the images you’ve shot in Sudan, Oman and Jordan? What did you want them to communicate?

I wouldn’t say I am trying to communicate anything precise with those pictures as single images. They are meaningful to me as part of a dialogue with the archive, as partial answers to some of the questions it poses, or as more or less flawed attempts of following its hints. Pictures are never innocent though. You can’t just go somewhere and do stuff, and there is no such thing as a pure gaze. The most banal of surfaces is a mystery once you look at it, and an enigma once you photograph it. Why did I photograph that thing and not that other thing? Is it because of what I am trying to say, or rather because of what I was told by others? I don’t want my work to be a statement; I prefer it to be something more open-ended, in which many of these exchanges are visible, so that viewers can adopt a critical stance.

What inspired you to explore the past of your grandparents in the first place?

My grandfather died in 1998, and I believe that death, in a way, is the mother of all stories. Fear of death might lie behind the urge to pass something on, and both the love and the fear of the dead are what inspire many of our rituals and of our myths. Stories are what connects us to the dead and the unborn—they are our most precious heritage. They are also mysterious, and come to us in bits and pieces. Most of them have been told once and again by different people, and have changed over time. One day my mother called to say that Granny had fallen, and that she was worried about her health. We both flew over to the UK, where she still lives in an old Victorian house in Horsham. It was a sense of urgency that drove me to ask her questions about her life and that of Grandpa, to open drawers, read letters, and unearth mysterious objects from dark dusty corners in the attic. I can now say, in retrospect, that I am glad I have done that.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Hereafter?

Of course I did. On one hand, there was all of the literature and the imagery that was produced in the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century as part of the effort to revitalize the ideological base of the British empire. The works of Rudyard Kipling, books like The Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T.E. Lawrence, or Wilfred Thessiger’s Arabian Sands. All of these were already referenced in the family archive. On the other hand, I relied heavily on Walter Benjamin’s concept of history and on Aby Warburg’s Atlas Mnemosyne in order to fashion my own method of interacting with the archive. As for the kind of work I wanted to make, I started out with the idea of classic novels like Joseph Roth’s Radetzky March or Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks, but then I stumbled upon W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, and although the result is very different, there is something in the way Hereafter works, as a constant digression, jumping here and there across time, that definitely owes to Sebald’s work.

How do you hope viewers react to Hereafter, ideally?

The only thing I hope is that there is a reaction. I cannot predict what it will be but I think people will react differently to it. This kind of work also draws its life from its openness. I think it is a valuable contribution because of how it lives between a private record and historical work, and because of how these two aspects are poetically woven into each other. It’s about my family but it’s also about family in general, it’s about a specific situation in a few specific places but I’m sure many other places share similar histories.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

There are so many, and all of them so precious, that it would take me ages even to remember them all. Some of them are people I have met, like my teachers and peers. Many of them are writers, painters, philosophers or poets, some of whom are alive. Many others are photographers, and many others just people who take photographs. Most of these I like and many others I don’t like, but they end up influencing me all the same. Maybe that’s what influence means—that you can’t really choose.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Again, there are lots. I would need to mention the work of Paul Graham: he seems to be able to change his approach to photography with each one of his works, and consistently to his subject matter. I particularly love New Europe and Shimmer of Possibility. Another contemporary classic would be John Gossage—I just love the way he works with the book form. There’s this book of his, Empire, that is a great example of how to build a relatively simple structure to deal with a very complex issue. Alec Soth remains my favorite storyteller, I feel the lyrical intensity of some of his works (Niagara, Sleeping by the Mississippi) is almost unique in the tradition of documentary photography. Collier Schorr’s work with portraiture, especially in Jens F., has been another milestone for me, as is Boris Mikhailov’s Case History.

As for more recent work, I am a big fan of Jason Fulford: I think he opened up some uncharted territory with his smart and playful combinations of photographs and text. The Mushroom Collector is still my favorite book of his, although Hotel Oracle has some wonderful moments. Then there’s Stephen Gill with works like Hackney Flowers, but also Archaeology in Reverse or Coexistence. I also think Christian Patterson’s Redheaded Peckerwood contributed a lot to photographic storytelling. I love the way the work of Jason Evans shoots off in so many interesting directions. Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs’s last book, Continental Drift, that came out this year, is maybe the most exciting book I’ve seen recently, along with Stephen Keppel’s Entre Entree in 2014 and David Campany’s A Handful of Dust. Then there’s younger people whose work I love, like Andrea Grützner, Sam Contis, Massao Mascaro, or Joanna Piotrowska.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Clicker. Shutter. Snapper.

Keep looking...

FotoFirst — Bucolic Photos of the Small Italian Town Where Massao Mascaro Found His Family’s Roots

Le Château Rouge — Enjoy the Beautiful Colors in Martin Essl’s Photobook

Girls Rule in this Indian Matriarchal Society (Photos by Karolin Klüppel)

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2019

India’s Greatest Epic Poem Relives in Beautiful Project ‘A Myth of Two Souls’

Beautiful Portraits by Erica Nyholm Explore the Role of Women in Family Relationships

Dylan Hausthor Explores the Power of Gossip in Mysterious Images