The Moon on Earth — In the Footsteps of the Astronauts Who Trained in Iceland Before Going to Space

In 1965 and 1967, two groups of NASA astronauts went to Iceland to get some field practice before going to the Moon: the island‘s most remote and hostile environments were assumed to be a good approximation of what they would have found on the Earth’s satellite. Upon discovering this story, 22 year-old British photographer Matthew Broadhead went to Iceland himself to follow the footsteps of those astronauts.

Hello Matthew, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

A state of equilibrium within what I share with the audience in different contexts is important—this comes in the form of balancing the empirical and objective with an emotionally subjective journey. Primarily I am interested in sharing and learning to find common interests and connect with others. I see the camera as a tool and photographs as an entrance point into discussion.

Please tell us a bit about the story of a group of American astronauts going to Iceland that inspired your series Heimr.

Throughout the 1960s and the early 1970s there were three overlapping space programs called Mercury, Gemini and Apollo. The Apollo missions are amongst the most well known: in 1969 Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon, walked its surface for two and a half hours and collected 21,55kg worth of samples.

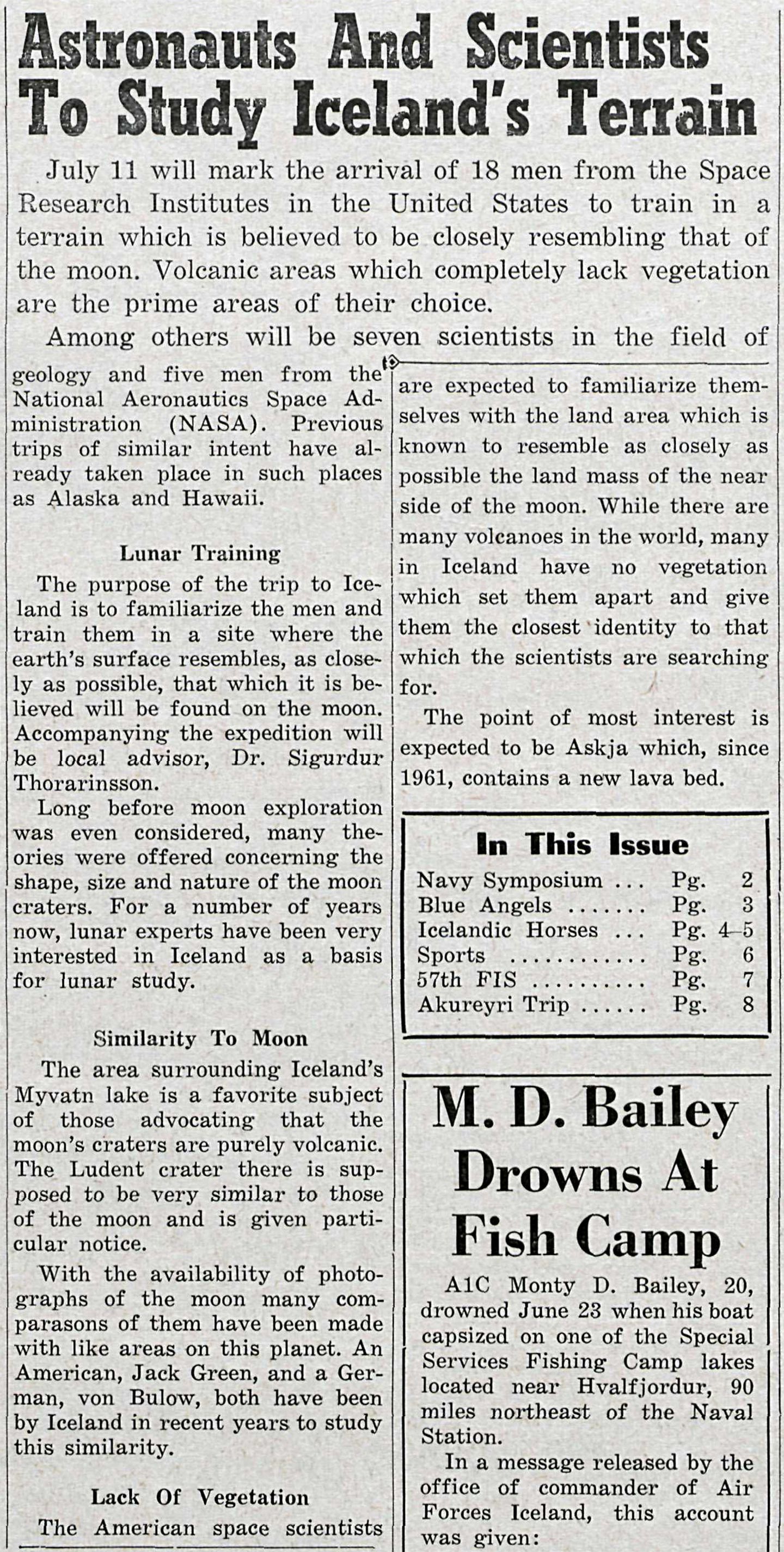

In preparation for this historic event, NASA and the US Geological survey worked together to organize an array of field trips across the geologically rich expanse of the USA, from Hawaii in the south right up to Alaska in the north. But two different groups of NASA astronauts and personnel also took a trip to Iceland, the first group in the summer of 1965, the second in the summer of 1967. Both groups were guided by two Icelandic geologists to locations described as ‘terrestrial analogue sites’ and nicknamed ‘space analogues’: places on Earth with assumed past or present geological, environmental or biological conditions similar to those of a celestial body such as the Moon or Mars.

At these sites, the astronauts practiced geology, learned about and identified varied geological phenomena, and played the ‘moon game’, a simulated interaction with a suitable test environment wearing space suit attire and using scientific equipment to collect samples and conduct experiments.

How did you discover this story, and what about it in particular inspired you to make it the base of your project?

While studying photography I wanted to embark on a project that was ambitious in scale and would take me far north, well outside of my comfort zone at that time. Before working on Heimr, I made a few attempts that developed my interest in geology and astronomy, and strengthened my will to base the project in a northernmost location.

Then, during a regular trawl on the Internet, I came across the story of NASA’s field trips to Iceland. The genesis of the project was the first phone-call I made to Örlygur Hnefill Örlygsson, owner of The Exploration Museum. The museum is dedicated to the history of human exploration, and hosts a permanent exhibition about the astronaut training in Iceland in 1965 and 1967. Örlygur was humble and enthusiastic about the prospect of collaborating: he offered me accommodation and full access to ‘The Exploration Museum’ to research and generate original material for the whole time I was in Húsavík. This gave me a lot of confidence and it’s been non-stop since that point. I always knew that the story was a great foundation that could be built on and refined, and I was excited to create a body of work that seamlessly combined many of my interests together.

The title Heimr is a reference to the Icelandic myth of Edda. Can you explain in brief what the myth is about, and how it fits your project?

There wasn’t a working title until the latter part of my time in Iceland. The owner of The Exploration Museum accommodated me in The Cape Hotel for my entire stay, and every morning I would come down to the breakfast room and explore a vast bookcase installed on the length of the wall. While browsing the books I came across a copy of MYTH: The Icelandic Sagas & Eddas by M. I. Steblin-Kamenskij.

Chapter two was interestingly titled “Space and Time in the Eddic Myths”—a synaptic connection activated in my brain. After reading the chapter I understood that the stories in Eddic myth were rendered in a similar way to the stories of NASA, and one line of text at the beginning influenced my understanding of what I wanted to say with the work I was doing. Steblin-Kamenskij wrote “The Eddic myths depict space only as far as portions of it are the location of some action or person” and followed this line with “Since space is discontinuous and finite, the world too in Eddic myths is only a bit of space, or the totality of such bits”. To put it simply, his description of the way the Eddic myth depicts space responded to my experience of collecting historical information about the geological fieldtrips in Iceland.

The series mixes images of old newspapers announcing the coming of the American astronauts to Iceland with your original photos of the country’s unique landscape. How did you approach photographing Iceland? What were you looking for from your images?

I was looking for a variety of different subjects brought into the frame by the small stories that emerged as I was researching. I don’t believe the concept of the work comes through in the technicalities of how my photographs are produced but rather the function of the single image in the larger body of work. My editing in this work was a process of distillation; photographs were removed if they didn’t stand alone in addition to communicating with the other photographs.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Heimr?

Both of the trips to Iceland were documented in an appendix of The Apollo Lunar Surface Journal edited by Eric M. Jones and Ken Glover, a record of the lunar surface operations conducted by the six pairs of astronauts who landed on the Moon from 1969 through 1972. It provided a solid starting point and foundation for my research.

In the library at the hotel I was staying at I shot a whole roll of film on books I thought were interesting and could help shape and develop the project further. One of these was the photograph of Axel Munthe’s The Story of San Michele published in 1929 that had a photographic print on top. All 32 chapters function as a series of overlapping vignettes that are described as not entirely in chronological order. The way that memory plays a role in this book inspired me to consider how the story I was trying to tell would be meaningfully represented, perhaps as a work of fiction based on fact.

More recently I acquired a hardback copy of Don E. Wilhelm’s’ book To a Rocky Moon: A Geologists History of Lunar Exploration. He was present during the 1965 field trip working for the U.S. Geological Survey as a consultant for NASA. Wilhelms was part of a scientific team responsible for assembling an overall picture of the Moon’s structure and history to recommend where on the lunar surface fieldwork should be conducted and samples collected.

Other important references were Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon; and The Geologic History of the Moon edited by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

I have a varied taste, there’s a wide cross-section of long lasting influences at play. The French art-house filmmaker Alain Resnais made a photo-film titled Statues Also Die. It highlights how the meaning of aboriginal art, specifically in French colonized Africa was stripped bare in favor of being consumed by the western contingent. It made me carefully consider how I represented archival holdings in the U.K. and abroad. A book titled Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method by John Collier, Jr. gave me an objective overview of how to work with people in a project and how to progress further to create a field study that was rich and illuminating. Very recently I purchased a book by Lukas Feireiss titled Memories of the Moon Age that unfolds as a study of the moon in art and literature well before engineers and scientists paid interest.

The best way to describe what shapes my practice is the conjunction between photography as a mediator and other subjects. With this approach in mind, what I learn about geology as a subject changes the way I interact and ultimately record what is in front of the camera in appropriate circumstances.

Who are some of your favourite contemporary photographers?

A few examples include the work of Salvatore Arancio, Geert Goiris, Alexandra Lethbridge, Awoiska van der Molen, Drew Nikonowicz, Christian Patterson, Regine Petersen, Alec Soth and Alberto Sinigaglia. These practitioners have in at least one way made me feel liberated about the possibilities in photography as a component and a critical subject.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

History. Document. Narrative.

Matthew Broadhead’s project Heimr will be exhibited at new photography festival Unveil’d in Exeter, UK from next 20 to 23 October (see here for more details).

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2019

Afterparty — Jussi Puikkonen Photographs Party Venues After the Parties Have Ended

Inzajeano Latif Has Been Taking Portraits of the People of Tottenham For Over Ten Years

FotoFirst — Gender Shifts Are Terrifying American Straight White Men, Shawn Bush’s Photos Say

FotoFirst — Federico Vespignani Follows a Youth Gang of One of the World’s Most Violent Cities

Atsushi Momoi Uses His Computer’s Screensaver to Visualize How Memory Works

Sem Langendijk Documents The Squatters That Established Their Community in Amsterdam’s Docklands