Echoes — Lauren Kelly Gives Voice to the Pain of Women with PTSD Due to Being Raped

Post traumatic stress disorder is a condition that affects the brain of individuals who experience a trauma, which can be anything from witnessing war to suddenly losing a family member. In her series Echoes — Growing Up with PTSD, 22 year-old American photographer Lauren Kelly focuses on women who, like herself, started suffering from PTSD after being raped at a young age.

Hello Lauren, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I would consider myself a trauma photographer. While working, I find myself drawn to the ideas of choice and healing.

Your series Echoes – Growing Up with PTSD is about women suffering from post-traumatic stress due to being raped at a young age. How does PTSD manifest itself, exactly?

When trauma occurs, the brain loses functionality in the hippocampus, which is the section of the brain that distinguishes between the past and the present. Consequently, for someone with PTSD, the boundaries between the past and the present can become fluid during a dissociation: here is not always the present.

For many women, PTSD manifests in paranoia, depression, suicidal thoughts, and dissociative episodes. A dissociative episode can be characterized as a period of memory loss, an ‘out-of-body’ experience, or derealization where the person affected feels as though reality is not real.

The work was inspired by your own personal story: you were the victim of a rape at the age of 14. How did that influence your life?

I don’t like to focus on where I would be if I never had PTSD, though sometimes I wonder if I ever would have found photography. My interest in photography began because of a disconnect in my own memories after the event. Photographs also have the ability to convey alternate histories—histories that do not necessarily claim to exist in one moment. It was cathartic for me to make physical objects that conveyed my reality. Once I began making my work and talking to other people suffering from PTSD who found ways to heal, I felt I started to heal as well.

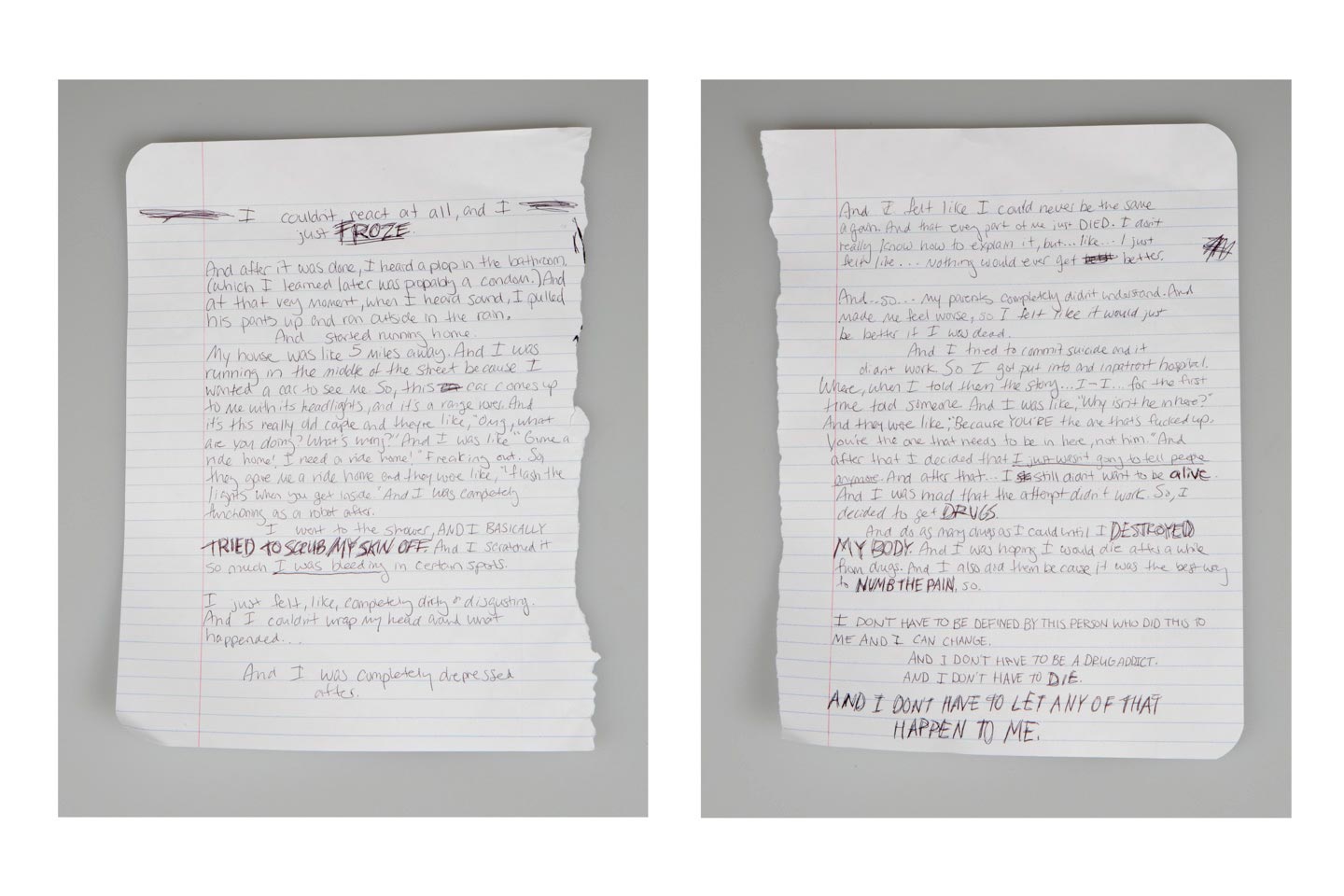

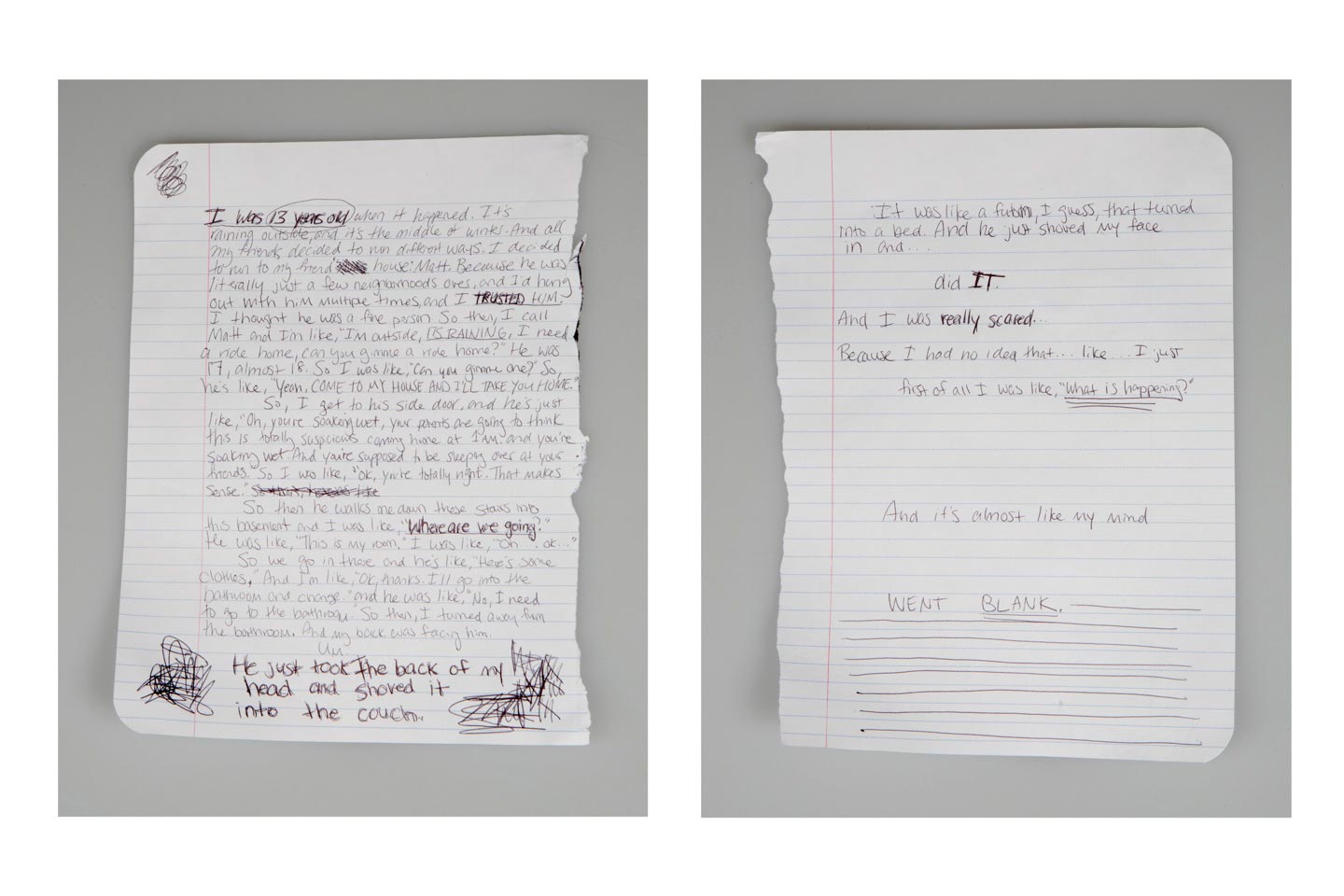

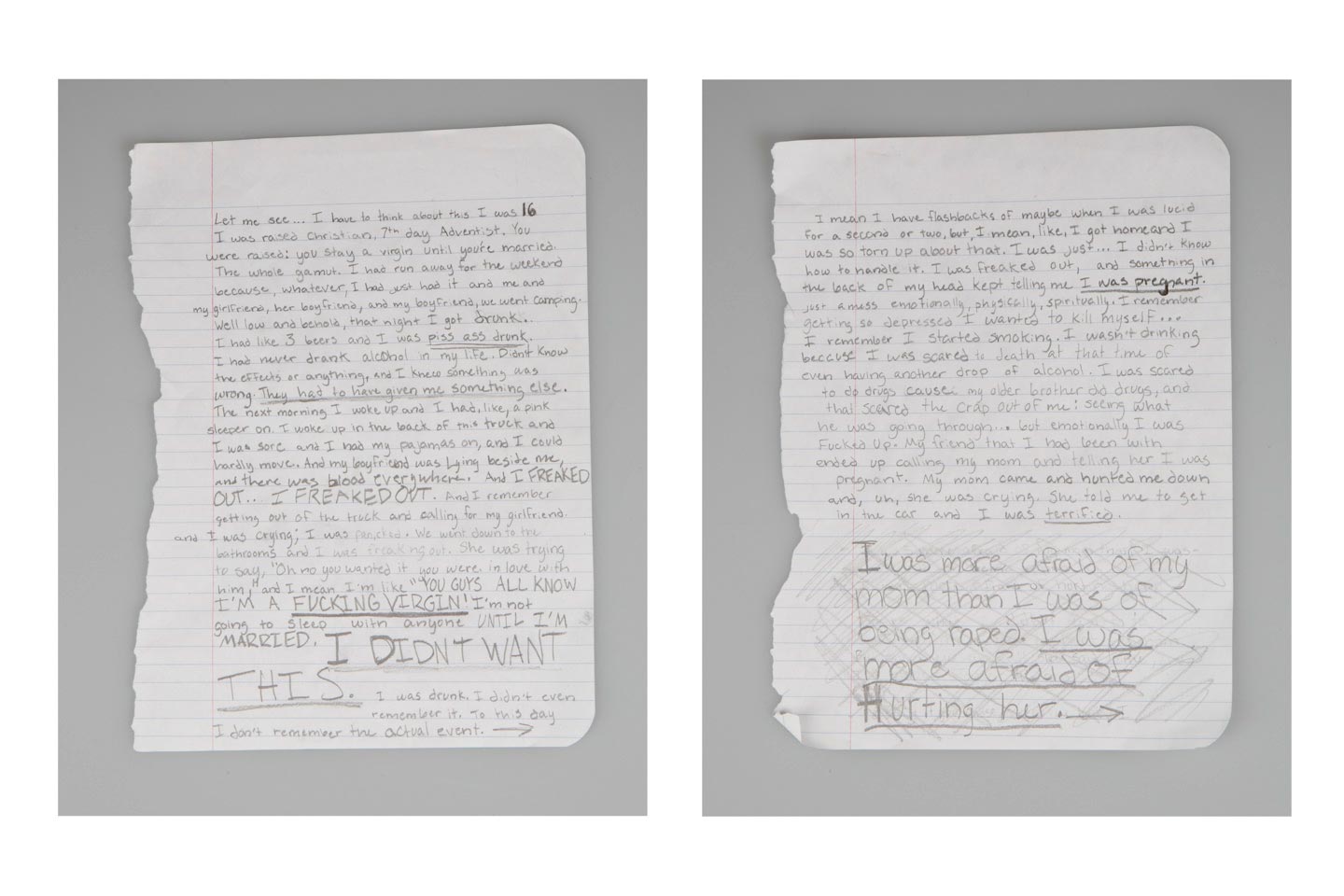

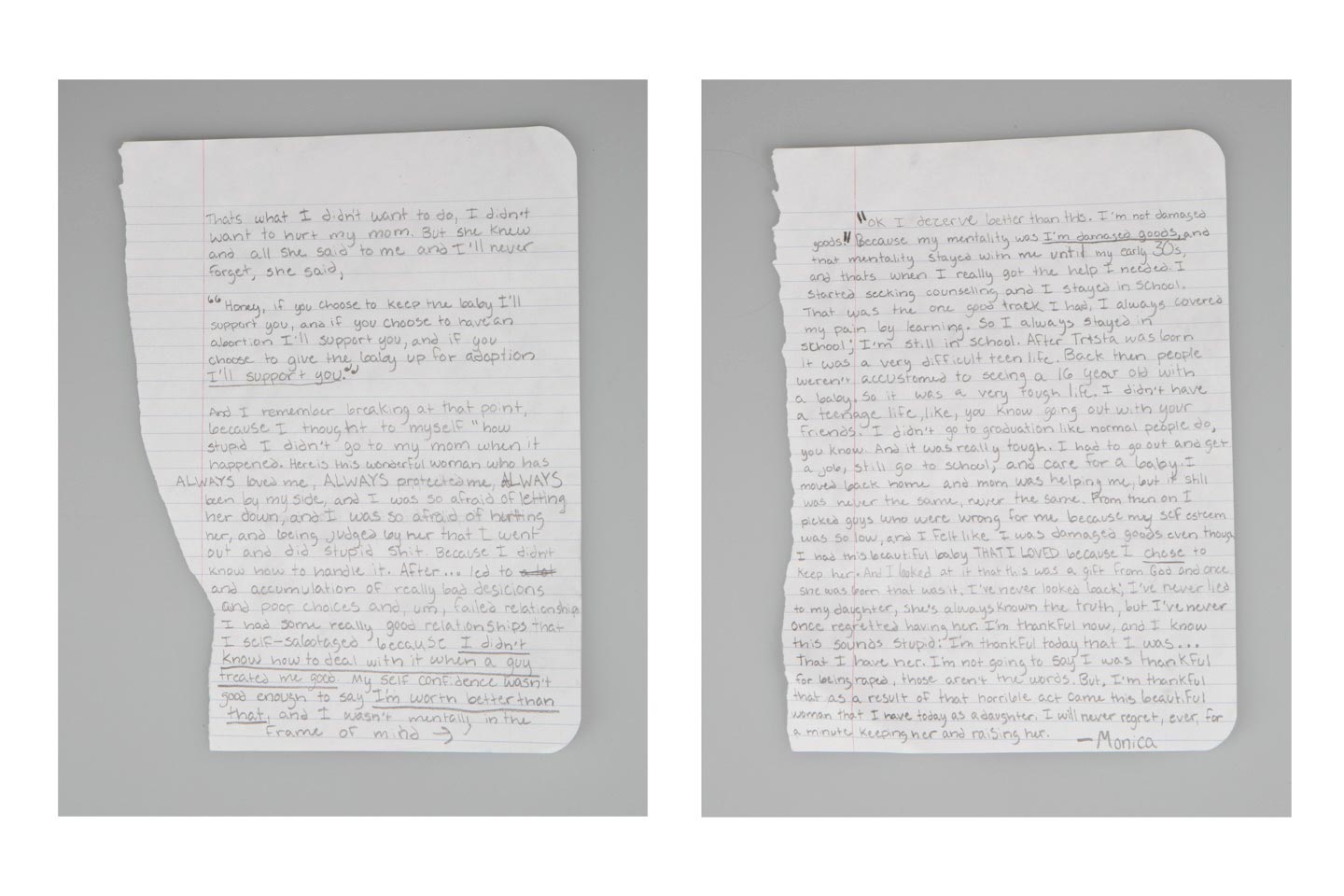

For Echoes, you first interviewed three women who were raped at a young age, and then created images based on their words. Can you talk a bit about designing that process as a framework for your project?

When I began taking photographs, I made a lot of self-portraits exploring my experience with body dysmorphia and PTSD. It was an extremely isolating process, and I needed to know there were people out there like me who were healing. I met the women through friends and through talking about the project. During the interview, my goal is to get people to feel comfortable and more importantly to feel heard. I simply ask, “What is your story? I’m okay with whatever that may mean to you, and you don’t have to talk about the rape if you don’t want to.” From there I ask questions related to aspects of their story, and I share some of my own story with them.

Many images show the outside and interiors of private homes. Were the women you interviewed victims of domestic rape?

Domestic rape more often refers to marital rape. The women in my series were raped at young ages and not by a spouse.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Echoes — Growing Up with PTSD?

While researching the best way to present the interviews, I began looking at the photographer Santu Mofokeng, whose work deals with Apartheid in South Africa. In his work, he photographs the culture of the people rather than the violence. One particular writing entitled The Violence is in the Knowing by Patricia Hayes, described his work as dealing with commonplace violence as an insider. One out of every six American women has been the victim of an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime. As a society we focus so much on the action of rape we forget about the healing, we forget about how this violence permeates in the long run. In my series I seek to expose violence often not talked about, the pain that occurs after. Many of the scenes in my photographs are not initially threatening or morbid, but when the text is read the images begin to change. The knowing occurs when the viewer makes the active choice to listen.

How do you hope viewers react to this series, ideally?

I want viewers to become active witnesses. People underestimate the power of making an effort to really listen to someone—particularly when that person is going through something as difficult as rape or sexual assault. Every person who has read these women’s stories has already made a choice to pay attention to them. I hope when they are presented with an opportunity to listen in their own lives, they make that same choice again. I also hope women who see my series and are currently going through this understand they are strong, they are not alone, and they will heal.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Redheaded Peckerwood by Christian Patterson, On This Site by Joel Sternfeld, Niagara by Alec Soth.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Christian Patterson, Joel Sternfeld, Eirik Johnson, Alec Soth, and Susan Meiselas.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Heal. Speak. Listen.

Keep looking...

Entrance to Our Valley — Jenia Fridlyand Shares Poetic Photos of Family Life on Her Farm

Men Don’t Play — Simon Lehner Investigates Masculinity on the Fields of Simulated Wars

Janne Riikonen Portrays Sweden’s Top Graffiti Writers

FotoFirst — Tianxi Wang Finds Solace Walking (and Photographing) Along the Hai River

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2019

Francesco Merlini Wins the Series Category of Void x #FotoRoomOPEN

The Baby Tooth Isn’t Loose — Brendon Kahn Captures the Fault Lines in Human Nature