Aerotropolis — Giulio Di Sturco Explores the Airport-Based Metropolises of the Future

We’re featuring this work as one of of our favorite projects of those submitted to #FotoRoomOPEN | Kiosk edition. (By the way, we’re currently accepting submissions for a new #FotoRoomOPEN edition: the winning series will be published as a photobook by Gnomic Book. Find out more and send your work).

Aerotropolis by 39 year-old Italian photographer Giulio Di Sturco is a long-term project about aerotropolises. But what is an aerotropolis? “It’s an urban form whose layout, infrastructure, and economy revolve around an airport, granting the businesses that operate in the aerotropolis fast connectivity with suppliers, customers, and enterprise partners worldwide,” Giulio explains. “The concept of the aerotropolis was popularized by the American academic Dr. John Kasarda and it’s founded on ideas like globalization and the transportation of not only goods but also intellect. An Aerotropolis is a model of a city driven by a combination of business needs and state control; it is a post-modern city, a vision or perhaps a mirage, a window of opportunities to solve the dilemma of modernity: reconciling economic development and sustainable growth. Although most existing aerotropolises have developed organically, in a spontaneous and haphazard way, in the future they may become more economically efficient, more pleasing to the eye, and more sustainable by adopting a synergic approach, which includes strategic infrastructure and urban planning.”

Giulio discovered about aerotropolises when he was commissioned to make a portrait of Dr. Kasarda by the FT Weekend Magazine: “I got a call in the evening and the shoot was the next day, so I didn’t have time to research who he was. When I started to speak with him he explained his idea of what an aerotropolis is. What stayed with me from our conversation was his point that an aerotropolis is not built for human interaction, but for business and connectivity. I felt that was the story I was looking for about how societies will look like in the future. Airports will shape business logistics and urban development in the 21st century as much as highways did in the 20th century, railroads in the 19th century and seaports in the 18th century. Yet there is a real question about mankind’s place in this new city format: the city does not seem to be built for men but for businesses.”

Aerotropolis was also a great occasion for Giulio to move away from his typical photojournalistic work towards a slower approach: “I became more interested in a long-term form of photography and was looking for a way to push the boundaries of documentary photography. In my opinion, photography is always evolving and we as photographers have to challenge ourselves to find new ways to explore the stories we choose to tell. When I met Dr. Kasarda I was looking for a topic that would help me slow down and distance myself from the fast action of photojournalism. Aerotropolis was perfect for that.”

An aerotropolis can be built from scratch or develop organically around an existing airport. Of the five aerotropolises Giulio has photographed so far, New Songdo in South Korea falls in the first category: “It is the very first aerotropolis ever built from scratch, based on Kasarda’s blueprint idea of what an aerotropolis should look like.” Giulio has also worked in Singapore’s Changi airport, Hong Kong’s airport, the Bangkok-Suvarnabhumi airport in Thailand (“a prime example of the failed aerotropolis“) and Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport. He’s currently working on five more aerotropolises in Europe and the USA.

Giulio’s main reference while shooting for Aerotropolis was Playtime, a 1967 film by French director Jacques Tati. “Tati filmed in ‘Tativille’, an enormous set that he built outside Paris where he reproduced an airline terminal, city streets, high-rise buildings, offices and a roundabout. The film is about modernity: how humans struggle to adapt to modern cities and technology, and are left feeling overwhelmed and ultimately alienated. Playtime was shot on 70mm film, a format that captures a larger portion of a scene than the standard 35mm film, with a higher level of detail. Tati only used medium-long and long shots—no close-ups, no reaction shots, no over the shoulder shots, etc. He shows us the big picture all of the time, and our eyes wander across the frame to find action in the foreground, middle distance or background. It is difficult sometimes to even know what the subject of a shot is.”

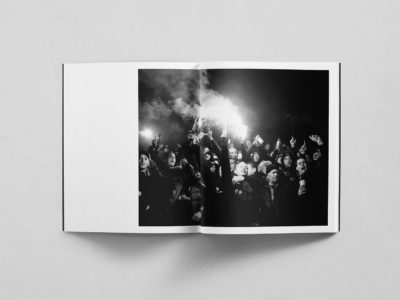

“The use of light and color and the way people felt insignificant in a modern city were the main elements of Playtime I referenced in Aerotropolis. I shot on a large-format analog camera to add one more conceptual layer and to create a contrast between the futuristic city that I was shooting and the way I was documenting it. In my images I try to capture something of the scale and beauty of these man-made cities while also hinting at the alienation and loneliness of its inhabitants.”

Giulio hopes the images of Aerotropolis will get viewers to reflect on the contemporary issues presented in the work: “For me, photography is a way to make the invisible visible, to reveal societal and environmental changes which are underway. Photographers should frustrate the viewers, push their imagination; we should not reveal everything in a picture, but rather give the viewer space to bring their own thoughts and emotions to the image.” The main influences on his photography all come from fields other than photography: cinema (David Lynch, Federico Fellini, Tom Ford) and the fine arts (Caravaggio, Bernini, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Edward Hopper and Francis Bacon). Nonetheless, he does follow contemporary photography and particularly appreciates the work of Nadav Kander, Paolo Pellegrin, Thomas Demand, Taryn Simon and Jeff Wall, “just to name a few.” Some of the last photobooks he bought are She Dances on Jackson by Vanessa Winship, Nowhere Far by Nicholas Hughes and The Last Testament by Jonas Bendiksen.

Giulio’s #threewordsforphotography are:

Metaphor. Invisible. Insecurity.

Keep looking...

Tomer Ifrah Visits Astana, Kazakhstan’s Planned Capital City

The Space Between Us — Evan Walsh’s Portraits Test the Expected Boundaries of Male Friendship

FotoFirst — Felipe Romero Tells the Macabre Story of the Bodies Emerging from the Magdalena River

This Is the (Photo) Story of the World’s Biggest Bonfire

Shane Rochelau’s Photobook Reflects on What It Means to Be a White American Man

FotoFirst — Discover Shahrzad Darafsheh’s Book of Photos She’s Been Taking While Fighting Cancer

Introducing Gnomic Book, the #FotoRoomOPEN Juror That Will Publish the Winner’s Work as a Photobook