You Could Even Die for not Being a Real Couple — What Love Is in Kurdistan

27 year-old French photographer Laura Lafon shares some background to You Could Even Die for not Being a Real Couple, a series of photos she took in Kurdistan as she looked for an answer to the question “What is love?”.

Laura is currently running a crowdfunding campaign to make the work into a photobook – show your support here.

Hello Laura, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

My work is documentary in nature, but it is also deeply related to my own experience of the world. Plus, photography for me is a way to discover far away places and meet new people. I use it to explore my own identity and to engage myself with the reality around me, I guess.

Please introduce us to You Could Even Die for not Being a Real Couple.

You Could Even Die for not Being a Real Couple is a self-published photobook about forbidden love in Kurdistan, with pictures made in 2013. The book is still available for pre-order on Crowd Books but it won’t be for long, so do it now!

How did you get the idea for this project? What brought you to Kurdistan in the first place?

In the summer of 2013 I was coming out of a long period when I had been very cynic, and wanted to approach “love”. I had a lot of expectations about it. Love is a universal feeling, but the ways we express love are not. They depend on individual choices and on the degrees of freedom and equality we enjoy. The Kurds are known to be a revolutionary people and great fighters for freedom and equality, especially when it comes to gender issues – they have integrated feminism in their fight for self-determination. Nonetheless, tragic stories of womens’ rights violation are often reported from Kurdistan. How can such a conservative and patriarchal territory tolerate these ideals of freedom? “What is love?” is a naive question, but it can lead to stronger issues.

What does it mean to be a “real couple” in Kurdistan, and what are considered “non-real” couples? What obstacles free love?

I guess a real couple corresponds to a man and a woman who are engaged and will get married with the consent of their families. In Kurdistan, being a couple is a social contract which extends to more than just two people. For example, you can be asked to prove that you are married if you want to rent a hotel room. Social conventions, conservative traditions and narrow-mindedness are the obstacles that stand in the way of free love.

Can you describe some of the stories that the young Kurds you met shared with you about being in love in their country?

Some of the conversations I had are reported in the book. The people I talked to have a very different, unromantic view on love than the one popular in the Western world. For example, they would often mention the woman’s virginity as a determining factor in a love relationship. Sex is also very problematic.

Many are also very critical of what is known as ‘feudalism’, that is having to follow the male leader from your family, tribe, village or wherever you come from.

The work also touches on gender inequality in Kurdistan. What are some things that are prohibited to women?

Basically the same things that women can’t do in other countries as well. Public spaces are usually separate for men and women – you can find only a few cafés with both male and female customers. Like anywhere in the world, it’s not safe for a woman to be alone in the street at night, but in places like Kurdistan it’s even more dangerous: the rape culture is very powerful there. Women cannot divorce or they get rejected – sometimes even killed – by their families. There are imperatives for men too. For instance, wearing earrings or long hair has been long considered a sign of insubordination, because a man has to look like a “real man”.

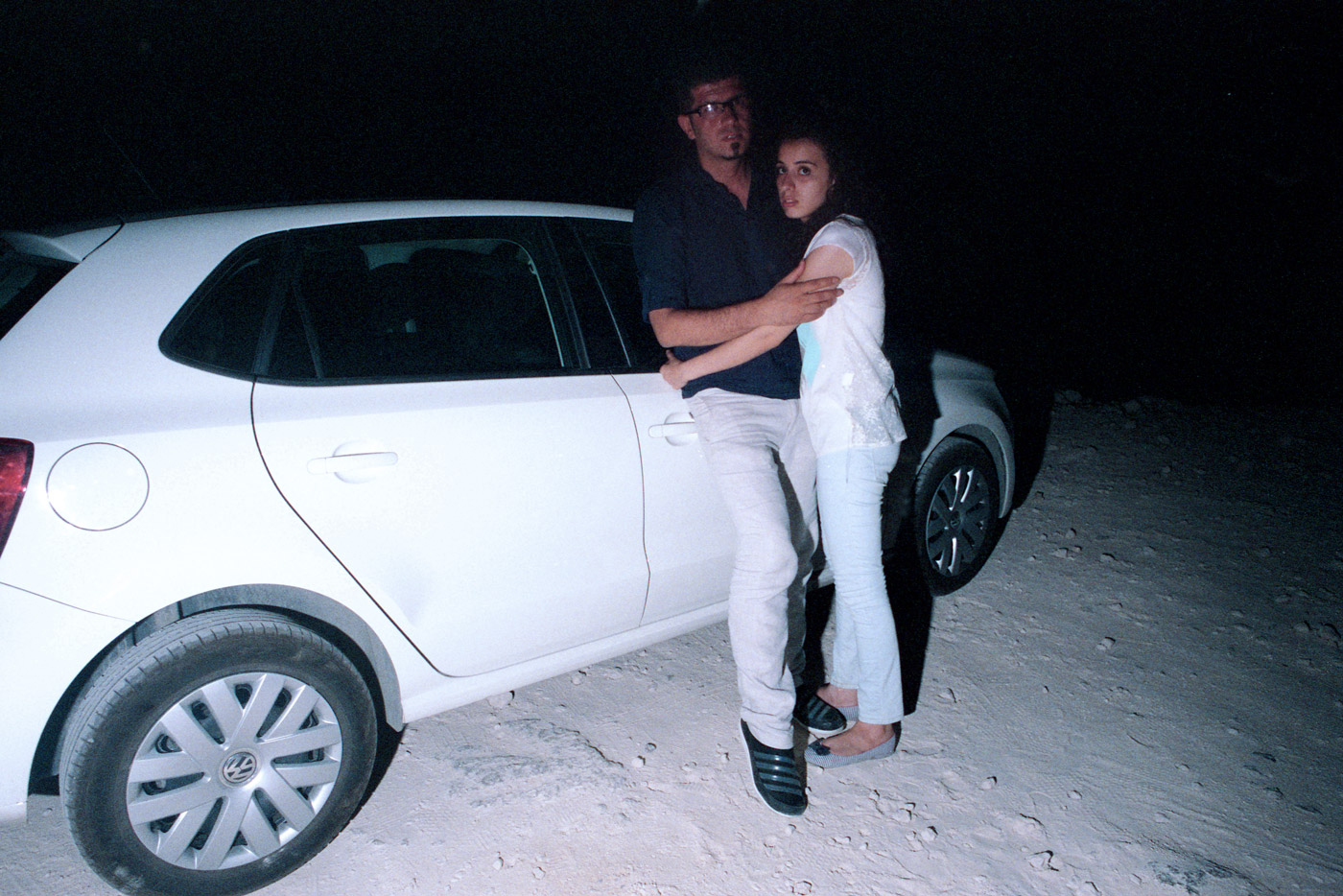

Most of the photos of You Could Even Die for not Being a Real Couple are of you and Martin, a photographer himself. Who exactly is Martin for you, and why did you decide to make this experience with him?

Martin and I used to call our relationship a professional duo, but laughed about it because we knew we were actually falling in love. We went on a few dates a couples of weeks before leaving for Kurdistan. I was supposed to go there by myself, but then I met Martin again at a music festival in Greece. After one paradisiac week of sleeping on the beach and eating gyros, I asked him to leave with me. He bought a plane ticket, and the next day we were in Kurdistan. It was chance, or fate. During the trip we started taking random self-portraits. It started like a game, but then we got to doing more and more of them.

What have you learned or realized from your trip to Kurdistan?

My main goal was to question my own place within society, and my vision of love. I’ve also been really impressed with the Kurdish resistance, and how fighting is so much a part of their identity. Thanks to them I regained some political engagement with the world around me.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on You Could Even Die for not Being a Real Couple?

As a political sciences student I had the chance to follow a gender studies course which changed my life and vision. It made it really clear for me that patriarchy and heteronormativity must be fought against.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Throughout my stay in Kurdistan I was listening to a France Culture podcast by Marie Richeux which became a strong reference because of her ability to create poetic images with words. Books by Annie Ernaux influenced me a lot too – she always creates fiction inspired by her own life with simple and striking discourse. Also, I finished my political sciences master with a thesis about self-portraits on social media – the word selfie wasn’t born yet. I studied the self-portrait practice in photography and discovered works from Joan Fontcuberta, Trish Morrissey, Boris Mikhailov or Nikki S. Lee. I didn’t have any image culture at this time and – considering the self-portrait project I made later – they influenced me for sure a lot!

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

I love more and more post-urss photographers like Sergey Chilikov for example. I do love Jan Hoek or Marion Poussier, Françoise Huguier or Taryn Simon.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Perform. Magic. Popular.

Keep looking...

Federico Clavarino Connects with His Grandparents’ Past as Ambassadors of the British Empire

Stranger — Olivia Arthur Looks at Dubai through the Eyes of a Shipwreck Survivor

The Gravity of Place — Israel Ariño’s Images Explore How Darkness Changes Reality

FotoFirst — Bucolic Photos of the Small Italian Town Where Massao Mascaro Found His Family’s Roots

Le Château Rouge — Enjoy the Beautiful Colors in Martin Essl’s Photobook

Girls Rule in this Indian Matriarchal Society (Photos by Karolin Klüppel)

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2019