To Sea Again — Faraz Pourreza Portrays a Community of British Ex-Fishermen Who Voted for Brexit

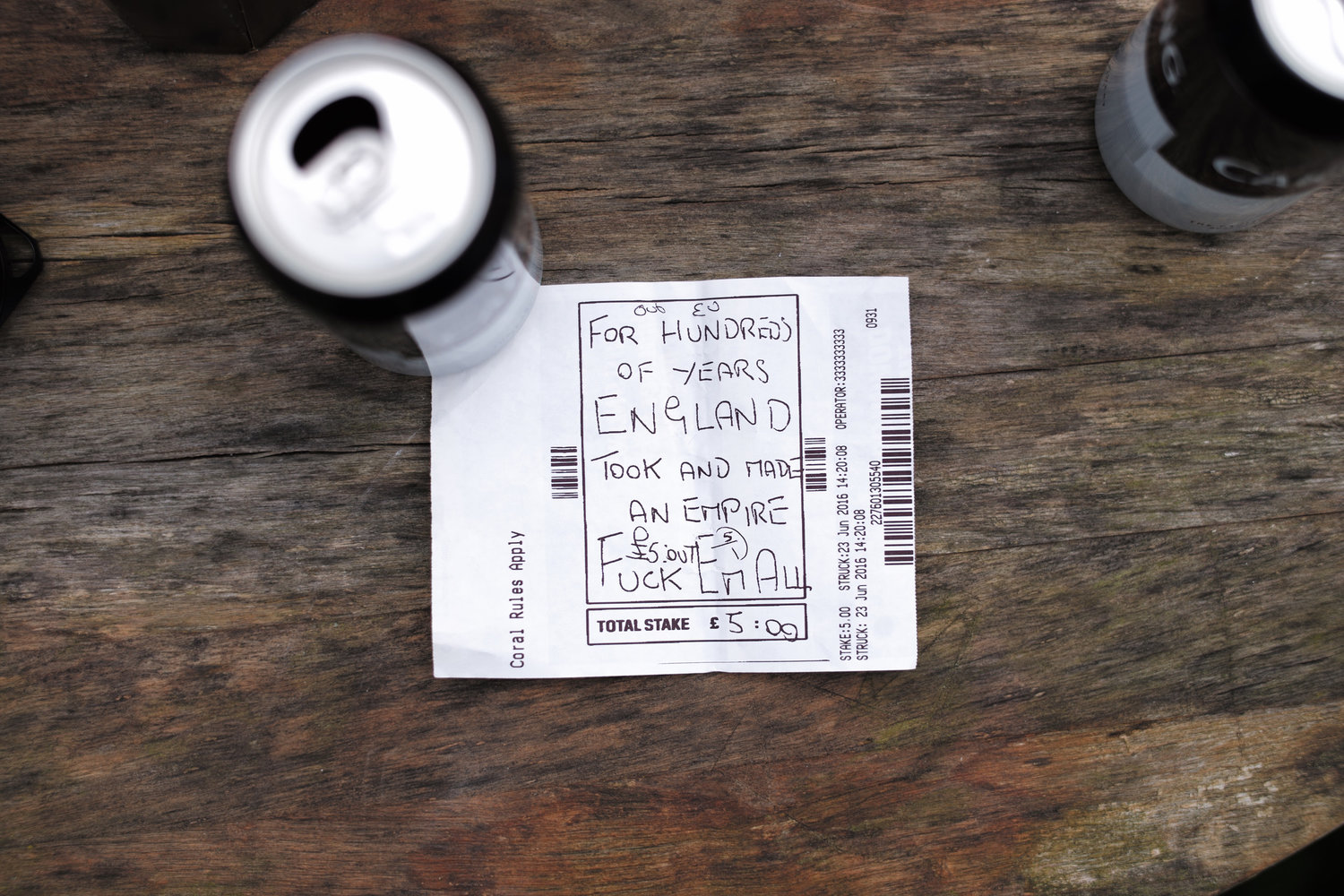

When last 23 June 2016 52% of those who voted for the Brexit referendum chose to leave the EU, many quickly blamed it on the alleged cultural inferiority of the UK‘s working-class, with whom the “Leave” vote was especially popular. For his subjective reportage To Sea Again, 31 year-old Iranian photographer Faraz Pourreza-Jorshari followed a small community of ex-fishermen located in Grimsby, UK. Since losing their jobs in the 1980s and unable to find a solid alternative, these men have been grappling with poverty and alcohol abuse: listening to their story and looking at what their lives look like might help in getting a grasp of the deeper reasons why they—and perhaps many other pro-Brexit citizens—decided to vote “Leave”.

Hello Faraz, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Hello, it’s my pleasure. The bulk of my work lies in the study of the human impact of deindustrialization on small working-class communities in the UK. I want to connect with ordinary hard-working folk who feel defeated by the immense injustices carried out by the powers that be, in hopes to dignify their history and bring public interest to their community.

Please introduce us to To Sea Again: what is the project about, and what inspired it?

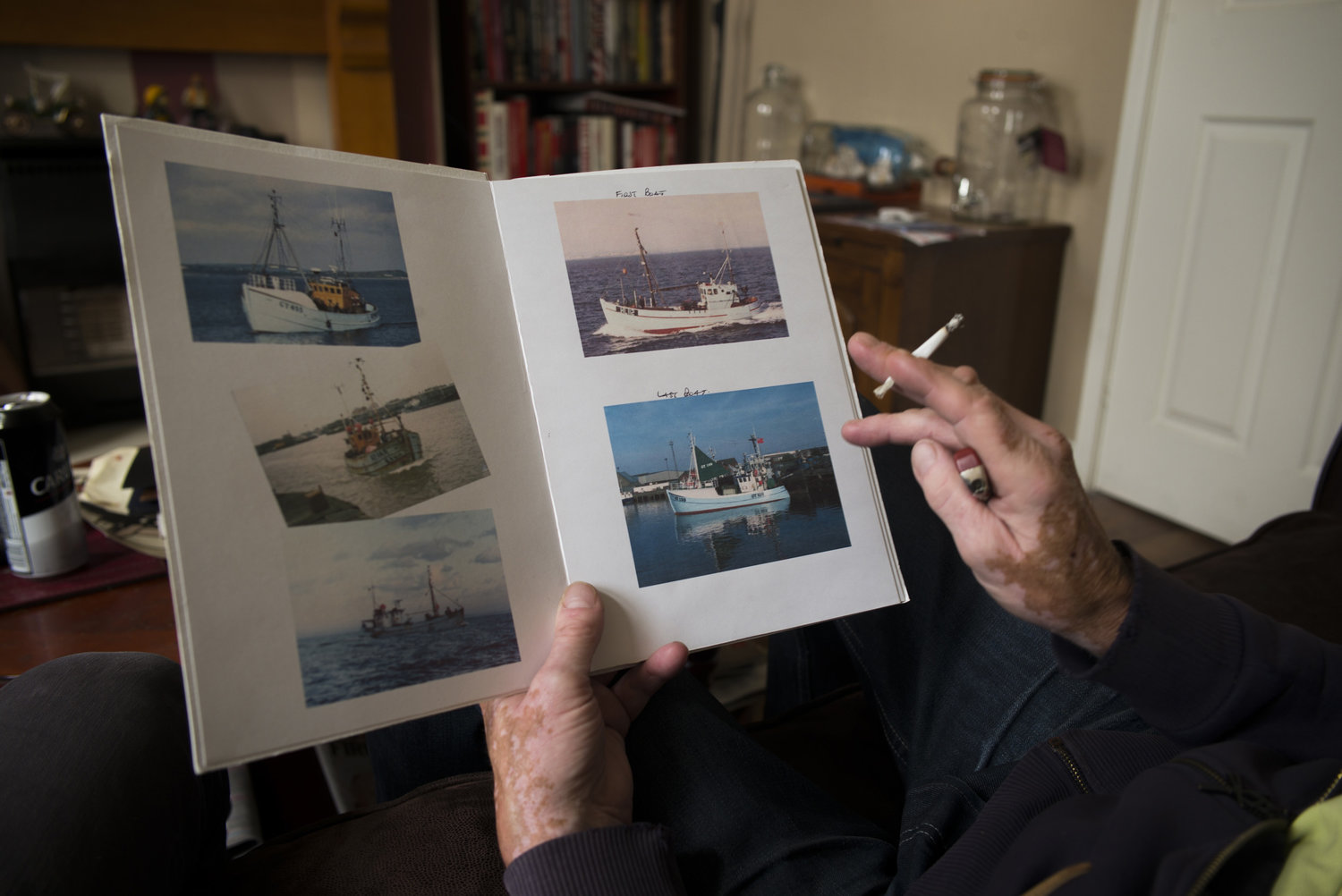

To Sea Again is a story about a loyal group of ex-fishermen living in a poor community called the East Marsh, in the northern town of Grimsby, UK. When their fishing trade ended in the 1980s, due to EU quotas and a series of international political conflicts between Iceland and the UK, thse fishermen were left feeling betrayed by the British Government. As a result of the economic and social decline, Grimsby’s identity and sense of community was shattered.

The media portrays the UK working-class through a very narrow aperture of selective information to fit a certain elitist agenda, and I felt inspired to highlight different truths about these communities. A Channel 4 TV series called Skint dedicated a whole season to Grimsby’s battle with long-term unemployment and poverty. Like most current TV shows, it seemed to only focus negatively on the extremes of the British class system, fueling hatred at the most deprived and least-educated. I wanted to follow the fishermen in an intimate setting to navigate around the general mainstream consensus, in an effort to fully grasp the reality in which they live. The scene is set in their housing estate called ‘The Square’, in the heart of the East Marsh.

For how long have you visited the fishermen of Grimsby, and how does life look like for them today?

I visited the ex-fishermen several times during a period of 9 months.

Today, with the fishing trade almost gone and government cuts to housing, education and health, the fishermen have fallen into a spiral of boredom that inevitably pushed many of them into alcoholism and substance abuse. It was terribly saddening to see such fierce, charming and intelligent men deteriorate by deliberate self-destruction. They were all family men but were divorced. This was another reason some ended up in The Square. The final return home from the sea left them with no opportunities.

During the time of documenting this group, three residents have already passed away. The main factor in all these deaths was alcohol abuse. The group considered their futures empty, so they immersed themselves happily in the past “back to sea again”. I find that The Square is their way of coping with the despair of their situation. It provided some form of solidarity, which was originally the cornerstone of the working-class. The Square gave meaning to their lives. Their sense of pride for their fishing heritage and community, however, was unscathed. Their political views have leaned towards the far-right, due to their worsening conditions and lack of representation. Hence, why they voted for Brexit.

Can you talk a bit about your approach to To Sea Again? What did you want your images to communicate?

Projects regarding people need considerable patience to be fully understood and to create an intimate connection with different realities. I pondered over my lack of cultural connection or identity with the fishermen, or whether I had a right to represent them as an outsider; but I believed that if I stayed true to their story, then it would be valid. I fully immersed myself with my subjects and felt extremely close to them after a certain length of time, feeling like I’d gained their trust and friendship. These were very complicated men, and therefore I wanted to give a surreal feel about the photographs. The inconspicuous Leica allowed me to portray the periods of raw emotion and chaos, together with moments of pure banter, comradery and love. I did this with the mindset of giving the viewer a moment to appreciate people’s differences and similarities.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on To Sea Again?

Several photographers such as Chris Killip, Raymond Depardon and Doug Dubois helped me understand the photographic importance of working-class communities. Most of my inspiration came from a journalist called Owen Jones, notably the book called Chav – The Demonization of the Working Class. He writes passionately about the history of the 21st century working-class and the causes of social inequality in the UK. Read it.

How do you hope viewers react to To Sea Again, ideally?

At the end of the day, I believe the viewer should make up their own mind on this subject. I definitely feel there should be a pause to see their humane side. I do feel people have the tendency to quickly judge the working-class, sometimes pinning the condescending words ‘underclass’ or ‘chav’ due to lack of understanding or empathy.

With the current world climate, where people are fully disillusioned by politicians and the elite, it is most vital to take time and listen to the voices behind Brexit and not to ridicule those that voted for it. I hope the project can enrich the viewers’ understanding of these fishermen. The dangers of leaving the EU did not resonate with them as their lives were already in dire situations. They will not be susceptible to these kinds of threats. Parallels can be drawn with the factors that led to Donald Trump winning the US presidency. People should always be included—not excluded—so that everyone can feel hopeful about their lives and strive to success. Grimsby requires a revival by addressing the social inequalities in our society.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

My family and fellow friends, notably my father, always gave me solid perspective and understood my relentless urge to express my thoughts through photographs. All my university colleagues played a pivotal role in shaping my understanding of documentary photography and a true tutor, Antonio Olmos, helped apply this to the project.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Chris Killip, Deirdre O’Callaghan, Tom Wood, Justine Kurland, Todd Hido, Doug Debois, Léo Delafontaine (thank you Edoardo), Gilles Peress, Jacob Aue Sobol, Kenneth O’Halloran.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Honesty. Patience. Humor.

Keep looking...

Witness to Beauty — Sage Sohier Celebrates the Unfading Charm of Her 89 Year-Old Mother

How and Why Palestinian Women Sneak Their Husbands’ Sperm Out of Prison

Subjective Trophies — Pierre Abensur Portrays Hunters Showing Off The Animals They Killed

Ten Best #FotoMobile Submissions Vol. 66

Hahn & Hartung Explore How Indonesia Puts Up with Volcanoes, Earthquakes and Tsunamis

FotoFirst — Los Angeles Becomes a Giant Movie Set in Gaudrillot-Roy’s Cinematic Work

FotoFirst — Photography Duo ‘Mount Fog’ Look at the Flooded Banks of Italy’s Longest River