FotoFirst — Shane Rocheleau Photographs the Homeless Men Living in His Neighborhood

Premiere your new work on FotoRoom! Show us your unpublished project and get featured in FotoFirst.

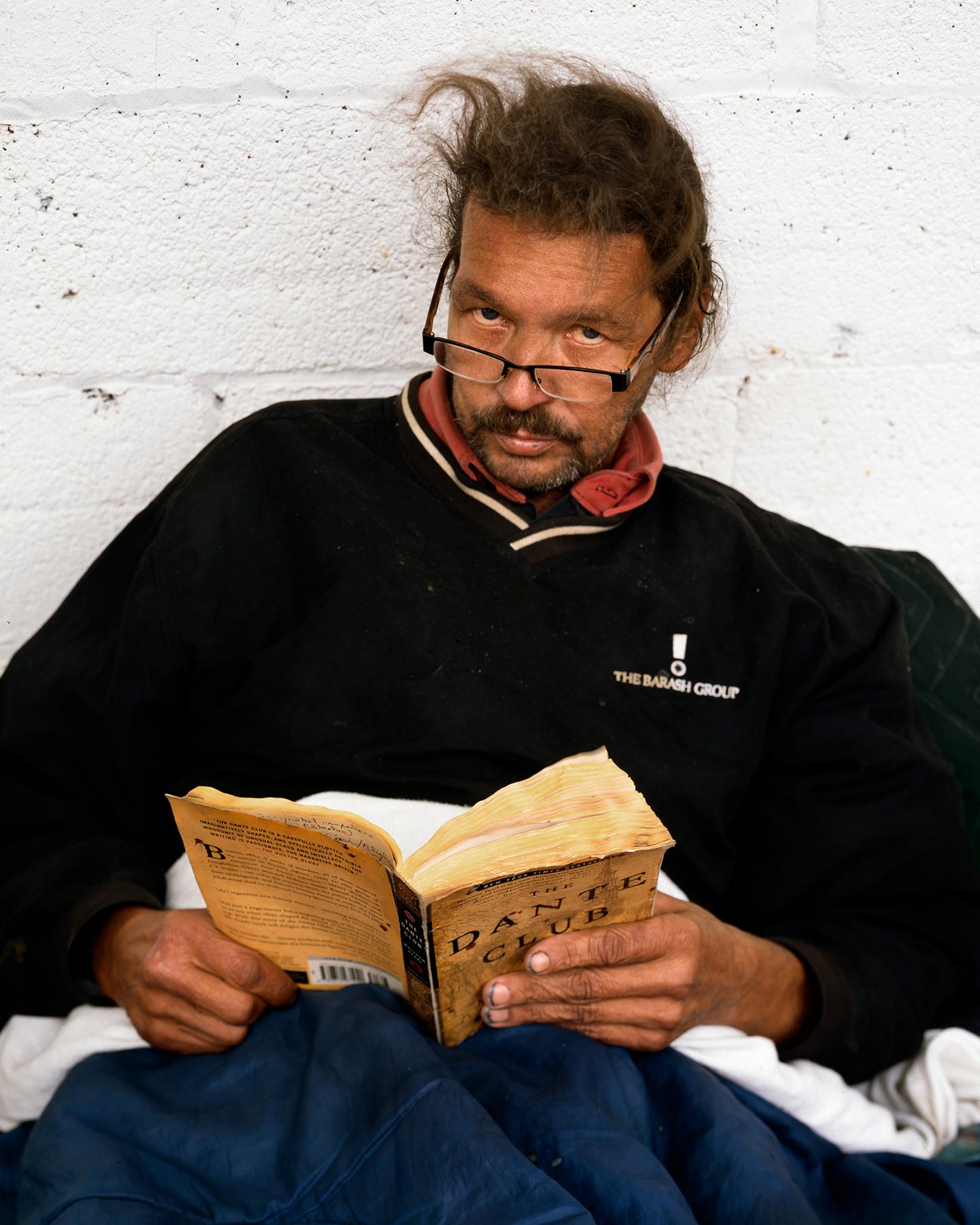

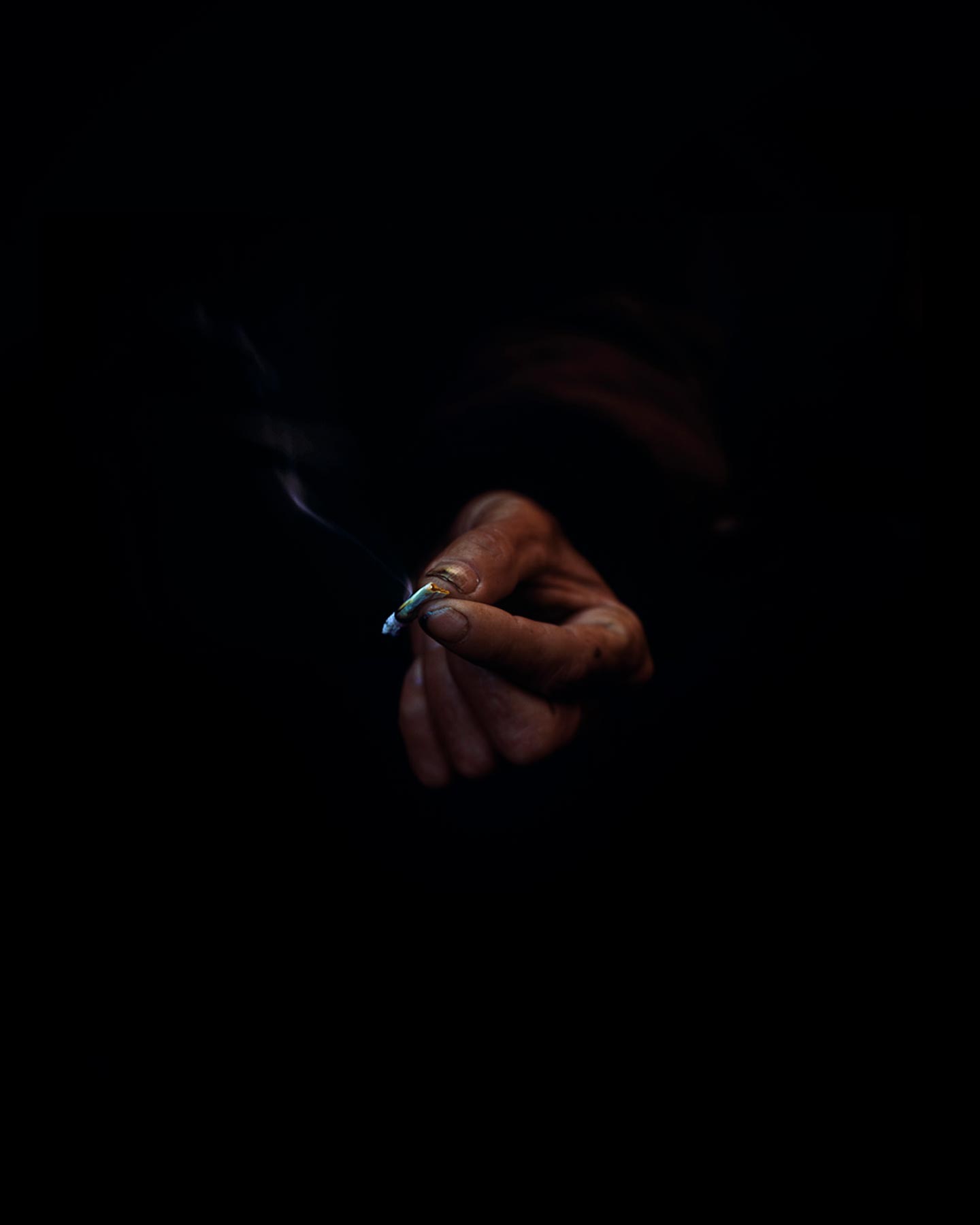

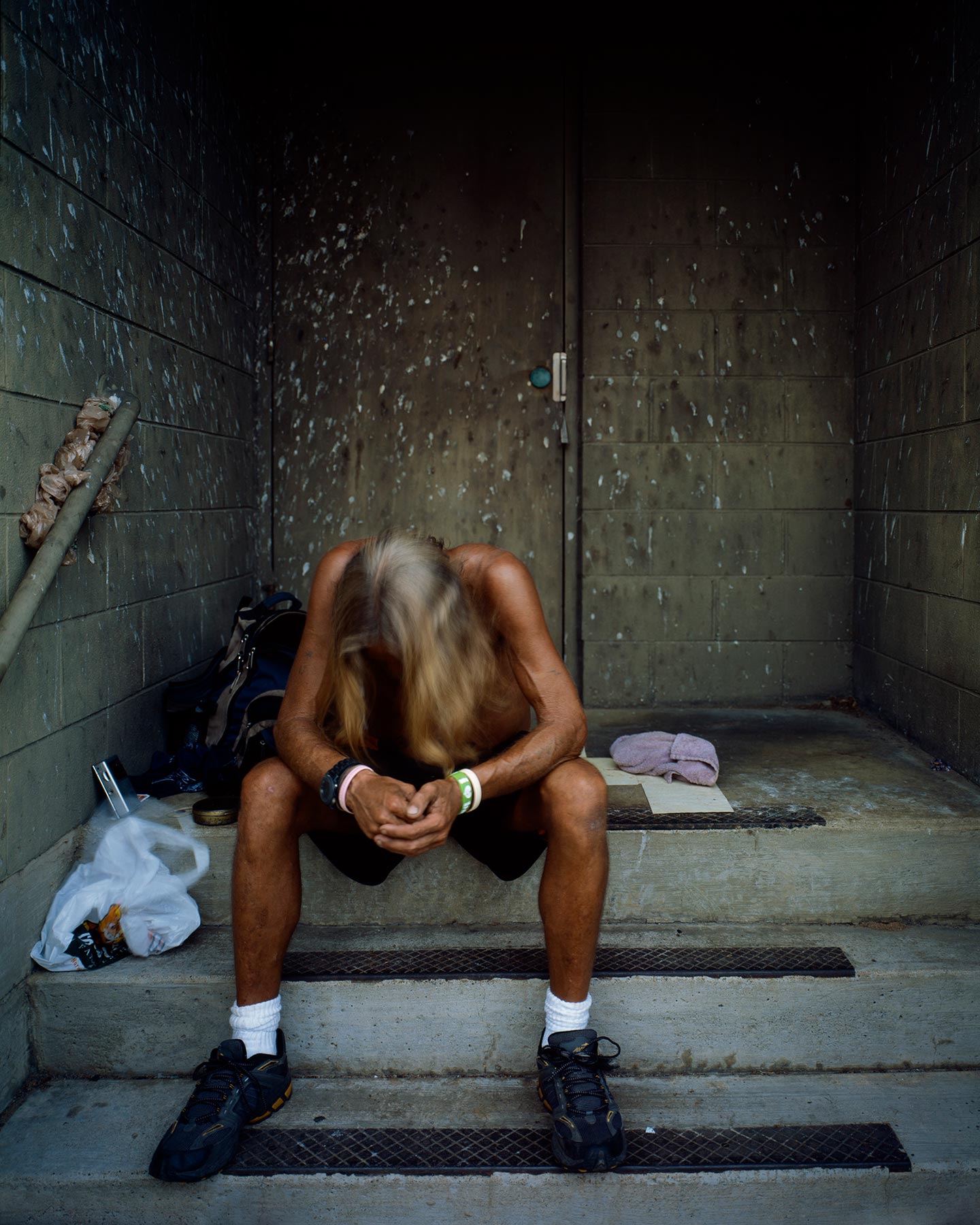

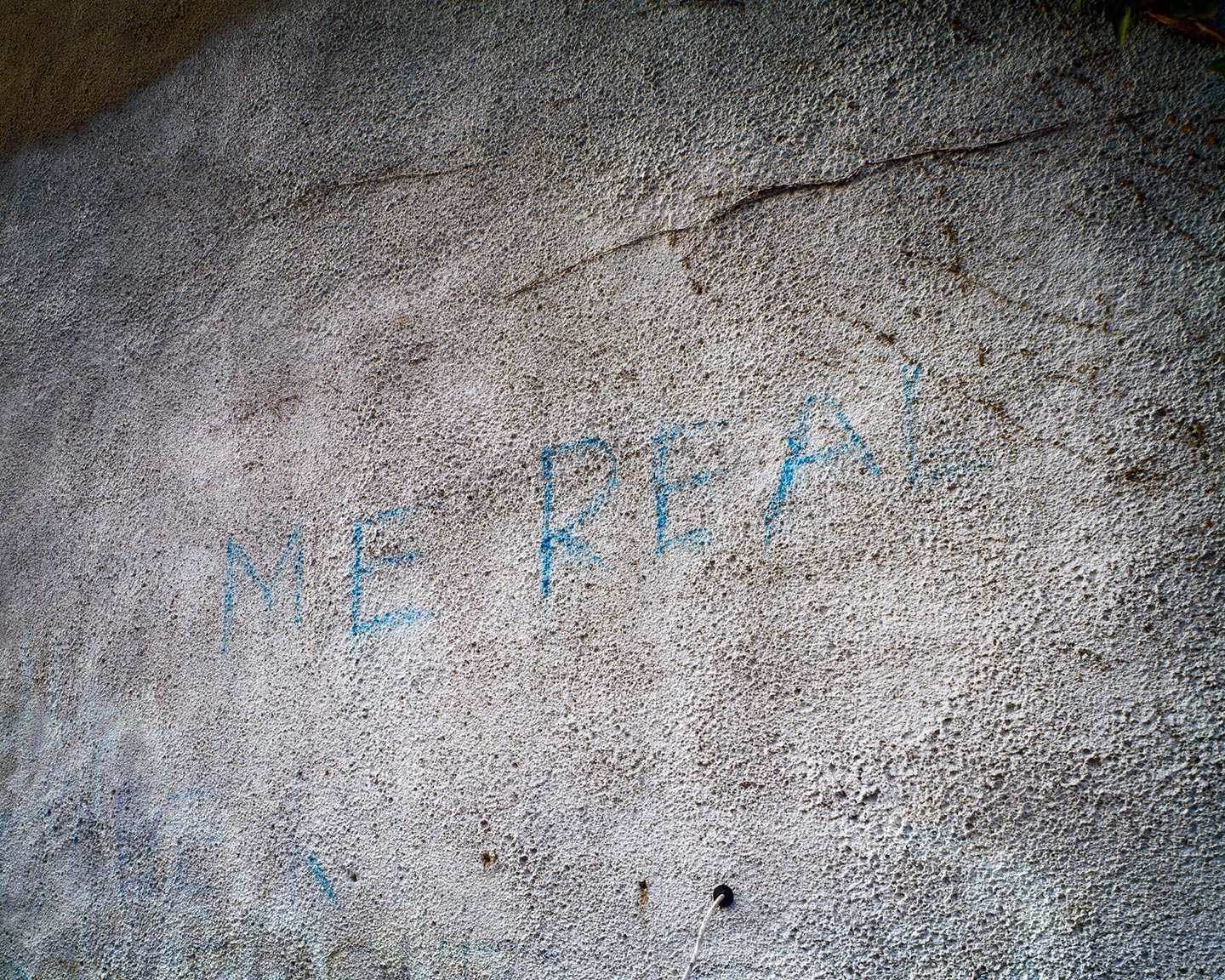

The Reflection in the Pool by American photographer Shane Rocheleau is a series of images and a photobook published by Gnomic Book (buy your copy) that deals primarily with homelessness. “About half the book is comprised of pictures I made of homeless men (there were very few women ever around) and their environs. The other half is comprised of pictures the men made with disposable cameras, as well as images of objects and pictures from their pasts. But while I do have an enduring interest in the condition of homelessness, I’m interacting with this specific group of men—and this theme—in order to also look at something more universal: the United States has an empathy problem. If that were not the case, toddlers wouldn’t be caged at our southern border due to their parents’ notional sin of searching for a life free from the immediate, visceral threat of violence or death. If that were not the case, our entire political and economic system would not be constructed to degrade African-Americans, and so many others who don’t look like me. If that were not the case, we might seek to reverse, or at least halt the decimation of Native American culture and natural rights wrought by genocidal policies and our subsequent indifference.”

“Homeless men are othered, too” Shane continues. “Most of us expend more energy finding a way not to look at them; I sometimes still reflexively look away from homeless people. But what if I attempted to truly empathize? That thought—or that question—was the genesis of this project. I realized that my own indifferent, ignorant behavior dehumanized and othered those suffering this social evil. The project is my attempt to reverse this behavior. I see active empathy as a road map to solving larger problems in my own life and, perhaps, in the divisive cultural lives of the American citizenry writ large. In setting out to make the work, I finally acted. These men were, quite literally, my neighbors, after all. They lived in tents three blocks from my comfortable apartment. One day, I parked my car near where they congregated, walked up to the group, and said Hey.”

Shane, who has seen his subjects for a continued period of time, has a hard time pinning down the connections he established with them. “I felt that some relationships were friendships, others were friendly, and yet others were latently and mutually transactional. I struggle with this question because—aside the already complicated photographer/subject (power) dynamic—there was another situational dynamic at play. Most of the men fought daily for their basic needs, faced with unthinkable obstacles. I provided anyone who asked with an easier way to meet these needs, when I could and only on a pretext of trust, not friendship, per se. I took some to the pharmacy for medications, or to the store for food or duct tape to fix a tent. I brought Lee to his family for Thanksgiving and Juan to the train station to start a new life in Louisiana. Bob would shower at my apartment because he was banned from the homeless shelter, and James would periodically ask that I take him to see his daughter. I never felt taken advantage of, though. I also know that I represented—in small or temporary or symbolic ways—a hope for something different, maybe better; and, some to me represented more photographic opportunity than prospects for vulnerable exchange. Like all relationships, these fluctuated and blurred and rarely fit any neat or singular conception of a relationship. I believe some saw me as a friend, but I don’t want to speak for these men any more than I already have. With the exception of Lee, I don’t remember any telling me that they considered me to be a friend.”

Besides the pictures made by Shane, The Reflection in the Pool includes images shot by his subjects on disposable cameras that he gave them. “I took great care to make the picture-making process a collaborative undertaking—to make pictures that granted each man his dignity and humanity—and to avoid certain clichés. It seemed a natural progression that their voices should suffuse the work, but I couldn’t find a way to effectively teach any of the men how to use my 4×5 camera (and this was the only option: it’s the only camera that I own). Enter the disposable camera. Eventually, it became a given that disposables be on my person. I handed them out to anyone who wanted to participate. If asked, I would simply say, “make pictures of anything you want to see, you want me to see, or you want others to see.” With the vernacular images peppered about the book and the title essay written by David Harryman (a shipbuilder who had been living rough for more than a year when I met him), I think these pictures give voice to persons we generally forget have voices, viewpoints, narrative, loves, losses. They are good pictures made by forgotten but deeply human people.”

Of his original photos, Shane remembers that “it took me more than a month to make my first photograph. I did not want to parachute in, then parachute out. Further, I wanted to show something more unresolved and complex, not merely the cliché of the homeless man on the street corner flying a desperate sign, face hollowed and emotionless. I don’t feel compelled to point fingers, but suffice it to say that I looked hard at projects by other photographers that elevate despair and disappear complexity. I’ve also loved Hunter Thompson’s gonzo journalism and works like Mike Brodie’s A Period of Juvenile Prosperity, but I think I saw a third way, perhaps one more akin to Doug Dubois’ My Last Day at Seventeen (though that work had yet to be published). While I got in deep sometimes—and sometimes dangerously deep—I did not become like Thompson’s gonzo persona, nor was I ever homeless as Brodie was a part of the culture depicted in his book. Each person represented in my book understood who I was (as much as that’s ever possible), that I was an artist, a professor, a father, a photographer. I tried to never get so deep that I all but erased this truth. Becoming homeless for the project felt disrespectful of their condition, and pretending felt worse.”

Shane believes everyone can relate to The Reflection in the Pool. “I think that we’re all looking for certain things in our lives: health, stability, love, happiness or contentedness, meaning, a reason for being. This is the condition of a human being. It’s my condition, your condition, and the condition of each person represented in the book. I hope viewers make this connection with the people in my book, and, by extension, all those they may routinely objectify and other. I hope each viewer sees the fullness of those human beings, the complexity, and, ultimately, a reflection of themselves. We are each mirrors for each other, whether or not we choose to look. I hope viewers choose to look.”

“American culture suffers from its own myths” Shane concludes. “It all too often (especially now) tells us that we are frontiersmen fashioning boot-straps to pull ourselves up by protecting the homestead and the hierarchies; it tells us that we are people empowered by didactic religious thinking about good and evil, best and worst. We literally created—out of our great American need for division and power—two races of people, aptly called white and black (when the Irish arrived, they were not considered white). The homeless are not, either. What I mean is this: the homeless are structurally positioned in our culture as other, and they are excluded from cultural narratives of normalcy, citizenship, democracy, entitlement, and agency (amongst so many others). We punish those who can’t conform, rather than give grace. Many of these people are punished. The most economically—not to mention, ethically—sound national solution to the problem of homelessness would be to provide a home to those without one. Yet this culture refuses in spite of the economic benefits that would ensue. We punish those who cannot rise to the challenge of the American Dream. We lay our Puritan roots bare, sentencing to humiliation those whose misfortunes and flaws deviate from the work of perfecting of our more perfect union. We punish at all cost. We should not punish—nor define ourselves against—the homeless. The homeless are filled with complicated, tragic, and joyful life experiences, just like you and me. They are part of our human story, as much as any of us.”

Buy your copy of The Reflection in the Pool via the Gnomic Book website.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2023

Discover the “Sweet and a Little Bit Sad” Photography of Annie Collinge