Yes, There’s Still a War in Ukraine — These Are the Men Who Are Fighting It

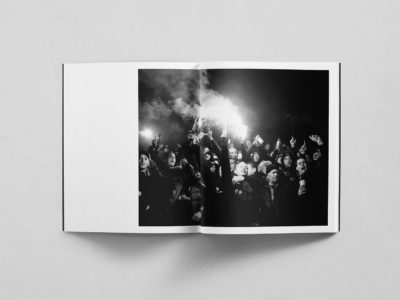

After extensive media coverage in early 2014 to follow the Euromaidan protests in Kiev and the annexation of Crimea by Russia, the civil, political and military unrest in Ukraine gradually, and rather quickly, disappeared from the headlines. But almost three years later, the warfare between independentists and pro-Russian separatists still goes on in the Donbass region of Ukraine. During this period, 25 year-old Polish photographer Wiktoria Wojciechowska has been working on Sparks, a mixed media project combining staged portraits, environmental portraits, collages and videos that document life at the time of war, with a focus on the soldiers and volunteers who are fighting to protect Ukraine’s freedom.

Hello Wiktoria, happy to speak with you again after featuring Short Flashes earlier this year. How have you been?

Thank you, it’s always great to answer your questions! For the last six months I’ve been traveling and collecting new ideas, memories, shells and stones. I made an amazing artist’s residency in the south of France, then visited my friends in China. Currently I’m just coming back from the Hafnarborg museum in Iceland where I’ve been making work with fellow artist Piotr Marzec.

Your latest series Sparks takes a look at the current war in Ukraine. What inspired you to make work about this war?

I was in China when the war in Ukraine broke out. I felt so distant—I was far away and safe while a tragedy was going on right next to my homeland (Poland and Ukraine are neighboring countries). I felt compelled to go back and see how the situation was for myself. I was really scared, but I was also very outraged by the news of the war. In the meanwhile, the media almost stopped covering the conflict in Ukraine. I considered it important to keep talking about it, and started the series by meeting soldiers and volunteers.

Sparks combines documentary photographs, staged portraits, collages and videos. Why did you choose this mixed approach?

It was a natural decision dictated by the fact that I think photography is not necessarily the best medium to represent all kinds of subject matter. The medium should serve the story, and for me it was more important to choose the right “language” to talk about different things.

In creating Sparks, I felt that as a first step I had to meet the people who were right in the middle of the war, so the portraits were the starting point. The words I heard from them made me think of going to the front line and photograph how daily life looked like over there, and then the rest followed. Everything that could show viewers the current state of things was good to exhibit, I thought.

Let’s talk about the portraits of the soldiers. Are they all Ukrainian? If so, why did you decide not to include any Russian soldiers in the project?

They are all Ukrainians. To clarify, officially, Russia is not taking part in this conflict: Ukrainians are fighting against the separatists, who are Ukrainians as well, which just adds to the tragedy. But from unofficial sources, we know that the Russian army is supporting separatists and fighting in Eastern Ukraine.

How can I explain choosing only one side? As I said before, my first motivation to create Sparks was the fear of a war coming—fear of invasion, death and non-intervention of other countries. People are dying and houses are being destroyed on both sides; but only one side is the invader. There is no excuse for invading, while there can be an understandable motivation for defending. There is no excuse for starting a conflict and destroying other people’s lives.

How did the portrait sessions go? What kind of images were you trying to make, and did you direct your subjects in anyway?

The process of taking the portraits involved talking with my subjects about their lives. My idea was to let them open up by listening to their stories and memories. The guideline I used in my approach was the question: is it possible to capture the difference between those who saw the war directly and those who didn’t? Are the sparks of the explosions still reflected in their eyes?

In Short Flashes there was the idea of catching a glimpse of truth in the emotions and grimaces of people cycling in the rain. In Sparks, the setting was completely different: an empty room, the light of one lamp, and the silence broken only by the words of the photographed person. Some sessions went on for a long time and resulted in many pictures that differed for small things—the corner of the mouth or a slight movement of the head. During editing, I selected the images where I thought I saw something opening up. Of course, this is my very subjective selection of pictures, one that also reflects me, my emotions and feelings about the person I met.

What did the soldiers tell you about the war? Why did they choose to fight?

They had different reasons for taking up arms. None of them were professional soldiers, but some were mobilized by the country when the warfare started. For the most part, they felt compelled to protect their country and families. Many of the men who started fighting at the very beginning of the conflict thought that it wouldn’t have lasted longer than a week or two. From what they told me, they realized that wasn’t the case when the first shellings started.

The images of the explosions many described inspired the title of the project: the “sparks” are the burning shrapnels. This word kept coming up in conversation—the civilians mentioned these little bright sparks coming from the sky like a sign of predestination, an omen of upcoming death. Valentina, a woman I met in the front line town of Mironovskiy, once said to me: “Shrapnels fell like sparks and pierced the wall, the sofa, the wardrobe and all the clothes”.

Can you talk a bit about the collages and videos included in Sparks?

The collages are made from pictures that some soldiers had in their smartphones—I covered the men in those photographs who have been killed with golden leaves. Of the many videos, some are documentary, others are more symbolic.

The more documentary part of the project consists of pictures taken in the battlefield, although in moments of calm. What did you want these images to capture?

I took these images at spots where men had been fighting from months up to a few days earlier: in all cases, all that is left is destruction. These photos evoke the silence after an explosion, the aftermath of when people hurt other people.

There are many symbolic elements in these pictures. The trenches, fires and interrupted roads hint at a country split in two: the land is telling a story of anger and lack of unity. Other pictures show destroyed houses—a house is a building which, for most, is the foundation of one’s identity. When you lose your home and all your belongings, it is difficult to find comfort again. These houses, in my opinion, reflect the current condition of the Ukrainians and their country.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Sparks?

I had in mind the old custom of soldiers having their picture taken in a studio before going to the war to give to their families. Often, these portraits used to be the first and last image of those men. It is very symbolic that each picture could be the last one, which I could feel the most watching the photos taken by soldiers during warfare. It is the first hand document of war and sometimes a gallery of death.

On the subject of war, I am always inspired by conceptual artists like Joseph Beuys, Christian Boltanski, Harun Farocki and Anselm Kiefer. I also read some books like Remarque’s great All Quiet on the Western Front, which I found out some of the soldiers I met have read in trenches as well. Other books I found very stimulating are Georges Didi-Huberman’s Images In Spite of All, Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others and Dubravka Ugresic’s The Culture of Lies.

How do you hope viewers react to Sparks, ideally? What are your next plans for Sparks series?

I hope viewers identify with the people who have to deal with the consequences of war. From what I observed at the different exhibitions of Sparks, the subject is very difficult to cope with for many viewers. It makes some visitors angry and some very sad; others want to suppress the idea that anything like that is happening. I think what matters the most to me as the one showing them these images is to inform them that there still is a war in Ukraine, get them to sympathize with the victims and understand that there’s nothing good about war. There is no excuse for it.

Keep looking...

Tomer Ifrah Visits Astana, Kazakhstan’s Planned Capital City

The Space Between Us — Evan Walsh’s Portraits Test the Expected Boundaries of Male Friendship

FotoFirst — Felipe Romero Tells the Macabre Story of the Bodies Emerging from the Magdalena River

This Is the (Photo) Story of the World’s Biggest Bonfire

Shane Rochelau’s Photobook Reflects on What It Means to Be a White American Man

FotoFirst — Discover Shahrzad Darafsheh’s Book of Photos She’s Been Taking While Fighting Cancer

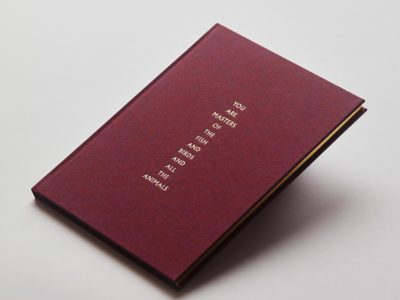

Introducing Gnomic Book, the #FotoRoomOPEN Juror That Will Publish the Winner’s Work as a Photobook