Intimate Distance — Photography Star Todd Hido Looks Back at the First 25 Years of His Career

If photography was Hollywood, American photographer Todd Hido (born 1968) would be a top actor like George Clooney or Brad Pitt. His fantastic images, and his photos of illuminated windows brightening up the nights of America‘s suburbs above all, have firmly positioned him as one of the best and most successful contemporary photographers. 25 years after taking his first steps in photography, Hido celebrates the first part of his career with a major retrospective publication recently released by Aperture—buy your copy here.

Hello Todd, thank you for this interview. Your new photobook Intimate Distance is a look back at the first 25 years of your career. Why did you decide to make a retrospective book?

After doing an educational book with Aperture, they approached me about doing a mid-career survey. And, after doing 25 years of work, and having the lucky problem of having most of my monographs being sold out, it made sense to have one photobook that contained the vast majority of my images so they could be available in a single volume.

How do you define photography, and what would you say are your main interests as a photographer?

My definition of photography comes from one of the very first classes I’ve ever had on the subject. In it, I learned that photography comes from the Greek, meaning ‘drawing with light’. I find that to be a suitable definition for the way I use the medium.

As a photographer, my main interests are finding or creating scenes that reflect some portion of my memory. Whether that comes through photographing a place or a person, I always seem to find an image that already exists somewhere in my past.

You are best known and loved for your night photos of suburban American houses and their illuminated windows. How did you start taking these pictures, and what do those windows represent for you?

I started taking these pictures in the same way I find all of my work: I simply go out and wander around and capture the things I notice. There was one particular evening, shortly after I had moved from the east coast to California, where I stumbled across a neighborhood that had two specific conditions that I found to be interesting: one, the homes were exactly the same style of homes that I had lived in as a child; and two, this neighborhood happened to be on a cliff near the ocean, which in California means dense fog much of the year. As I drove through this area, I was stunned by the surreal nature and the spookiness that this fog seemed to cast over this seemingly typical neighborhood.

As far as what the windows represent to me, they clearly are a portal into one’s imagination. I would suggest that in each person that views them, including myself, the meaning of the image resides in the viewer.

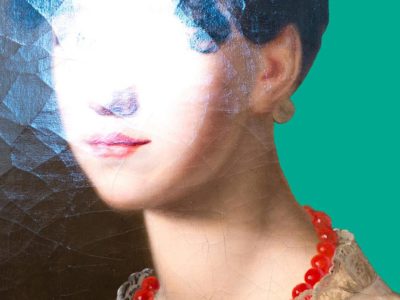

The other main subject of your personal work are women—you’ve often photographed them nude, in rather desolate bedrooms. What are the origins of this “iconography”, and how do your pictures of women stand in relation to your pictures of suburban homes?

To me, I have always approached both the people and the places I have photographed in the same manner. There is something that I see in the women I photograph that is very familiar to me and resonates in some way with my history. At the same time, the models that I often photograph are approaching me with a similar desire to express or revisit something from their past. All the scenarios in my work that involve people are constructed images and are highly collaborative.

You’ve photographed your preferred subject matter over and over again during these twenty-five years. What keeps it interesting for you?

I’m always looking for an iteration of whatever it is that my photographs express. I have photographed houses at night, interiors, landscapes, and portraits for many years and there are certain points when I am highly active in one specific category and other times when there will be years and years between me adding to a group of pictures.

As an artist I have always felt that my task is not to create meaning but to charge the air so that meaning can occur. In all my pictures of people or places I see something of myself. It is no mystery that we can only photograph effectively what we are truly interested in or—maybe more importantly—are grappling with, often unconsciously. Otherwise the photographs are merely about an idea or a concept—that stuff eventually falls flat for me. There must be something more, some emotional hook for it to really work.

The book’s title Intimate Distance alludes to your way of photographing. Can you elaborate a bit on your approach to photography, and why you put that distance between yourself and your subjects?

I think that my particular approach to photography stems from my love of many different aspects of the medium itself, which is one of the reasons that I often work in multiple genres concurrently. My approach very much vacillates between my love of documentary and my desire to express myself emotionally with images.

Perhaps the most frequently used adjective to describe your work is ‘cinematic’. Was cinema in fact an influence on you? If so, how did it shape your practice, and is there a specific type or genre of films that resonates with you?

It’s funny that people often think that my images are influenced by cinema as I actually don’t watch many films. I think that my approach to making pictures very much comes from an idea that Lewis Baltz put forth and that I discovered when I was a graduate student twenty years ago: he said that he found photography to be a profound corner that sat in between literature and film. I know that I have often thought about that when making pictures, and I have embraced the silence and incompleteness of a photograph. I very much enjoy working with those limitations to create something that has ambiguity.

How do you hope viewers react to your images, ideally?

It’s not something I really even think about. What I think about when I am making things is how I react to an image. That is not to say that I am oblivious that there is an audience to my work; but I honestly don’t make my pictures for anyone but myself. When I make something that moves me, then I know it’s right.

FotoRoom is followed by many young photographers. What advice can you give them about finding a voice in photography?

The first thing I would say, is the voice that you will hopefully find in your images does not exist anywhere but within yourself. The most important thing is to trust your instincts and go with your intuition. I have solely followed my intuition in leading me throughout making pictures for 25 years. At some point in time, what I was doing was absolutely not considered interesting or “of the moment,” but that’s not what my goal was to start with, so it was of no matter. Simply put, I suggest that you follow your gut, make what you want to make, make a lot of it, and pick the good ones. Finally, I would say: be a very critical editor of your work and don’t be afraid to let go of the things that aren’t good. Put your work forth into the world only once it has been tightly edited and when it’s truly finished.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Exploration. Intuition. Expression.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2019

Viviana Bonura Is Using Instagram to Share Photos of Her Parents as a Young Couple in Love

FotoFirst — Carlo Rusca’s Pictures Create an Imaginary Location in Black and White

Pierre-Elie de Pibrac Takes Close-up Portraits of Cuba’s Guajiros

Johanna Naukkarinen Wins #FotoRoomOPEN | Vasli Souza Edition (Single Images Category)

Alexander Mendelevich Wins #FotoRoomOPEN | Vasli Souza Edition (Series Category)

Ronghui Chen Meets the Young People of Northeastern China