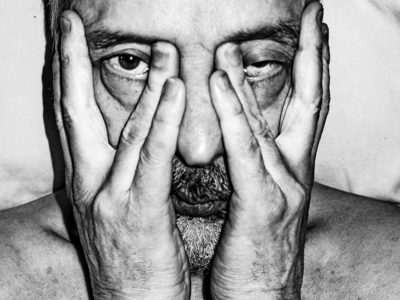

Homeland — Georgs Avetisjans Recreates in Images the Fishing Village He Left Years Ago

Looking at the images of Homeland, a series by 32 year-old Latvian photographer Georgs Avetisjans, it’s hard to believe that they were shot between 2015 and 2016. The photographs capture the landscapes and people of Kaltene, a small village of fishers in Latvia that would seem to be suspend in time; in fact, the work is a subjective reportage on the line between reality and fiction in which Georgs recalls the village he grew up in as a child, upon returning to it after many years away. Homeland is also available as a photobook.

Hello Georgs, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Hi, thank you so much for having me. My main interests mostly lie in the field of documentary photography, photobook making and how combining photography, design and materials can possibly shape the story of an entire photographic project. Years ago I started to explore subjective aspects in documentary photography such as moods and symbols, which formed—and I believe still form—my visual narrative. I’m also very interested in themes like regional and national identity, ethnography, memory, nostalgia, existentialism and metaphor.

Please introduce us to Homeland.

Homeland is a multi-layered narrative within a hand-made photobook (the first edition was self-published in 2016) about the village of Kaltene and its recent history, presented through interviews, notes and vernacular imagery. Kaltene is Latvia‘s longest fishing village: it extends for about 7km along the Gulf of Riga and was founded over four centuries ago. In ancient times, Kaltene was especially known for the sleek, branchless trunks of its pine trees, which were exported to Western Europe to be used as masts on ships, and apparently lasted about ten times longer than masts made from other trees. In ancient Danish, the village’s name Kaltene means “naked tree”.

My project is a story about sea, land and memory in Latvia’s longest village, and about how time affects and changes our sense of place. It depicts a quiet and safe small town with which every viewer may relate through their own memories of other villages or natural locations that they’ve been to. In Homeland, Kaltene also becomes a metaphor for a way of life or the passing of time.

The best way to engage with this story is to have the book in your hands—touching it, opening it, feeling it. Through the book you can learn much more about the protagonists’ lives, or travel through your own memories by reading theirs. Homeland is also documentary in the sense that it captures daily life in an actual geographical location and adds an extra layer to the representation of this village in Latvia, or of Latvian identity more generally.

What inspired Homeland, and what was your main intent in creating this series?

My Greek-Armenian father came to Latvia during the Soviet era. Shortly after, he met and married my mother, who is Russian-Latvian. One day, in the early 1980s, my dad and a very good friend of his decided to drive northwest from Riga in search of a place to build a home. Dad had always wanted a house by the sea. Back then, as his friend once told me, they stopped in Kaltene and admired the amazingly tall pine trees in the forest and huge rocks by the sea. Right away my father knew that that was where he wanted to live for the rest of his life and raise his children; unfortunately, he passed away when I was only 6 months old.

The idea of my father building our family home by the sea was the actual starting point and inspiration for my project. Kaltene is my homeland, the place where I’ve spent my childhood and of which I have so many fond memories. After being away for so many years and re-evaluating my own feelings and thoughts, I decided to return and recreate my homeland through photography, to retrace the place, its landscape and identity.

How would you describe your approach to the work? What did you want your images to communicate?

I was really interested in a multi-layered, research-based storytelling about contemporary issues, including historical and ethnographical aspects. Working on the project I’ve developed several ways of integrating themes of identity, history, memory and ethnicity into a visual and personal story through the book’s interactive design.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Homeland?

My sources of inspiration in terms of photographic ideas were Marlene Creates’ The Distance Between Two Points is Measured in Memories (1988), which explicitly engages the relation between social groups, memory and place; Dragana Jurisic’s YU: The Lost Country (2011-2013), a photographic project about Yugoslavia; and Vèronique Kolber’s Appearances (2003-2005).

In terms of photobook making, my very first inspiration was Paul Graham’s book The Present where he successfully used foldout pages to present and emphasize the notions of past and present, today and yesterday—I used a similar strategy in the Homeland book. Another inspiration was Jack Latham’s first book A Pink Flamingo, of which I liked three things: the layout of the images, the book size and the paper pocket where a map is inserted. I was also inspired by Kazuma Obara’s book Silent Histories, a very well considered photobook that expanded my vision of how a great book can be made. Finally, I looked at the very well designed publication: Hikari – Talents 35 by David Favrod and Julia Katharina Thiermann.

How do you hope viewers react to Homeland, ideally?

It’s a difficult question. I believe that Homeland is a project for everyone, not only for those who appreciate photography. I don’t really like to give any direction on how to view and engage with the project: it should be a personal and individual choice. In general, it’s a story that allows viewers to travel through their own memories—there are no any limits or restrictions.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

I’ve looked up to Latvian photographer Andrejs Grants since I was a child. I have found many of his original hand-printed black and white photographs in our family drawers, he used to send them to us even before I was born. I often returned to those drawers with curiosity, fascination and excitement. Later in life I’ve also attended some of his documentary classes in Riga.

Other great influences for me were the works of photographers like Robert Frank, Mary Ellen Mark, Diane Arbus, Martin Parr, Paul Graham, Jeff Wall, Alec Soth, and cinematographers like Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

If I have to mention just a few, I’d say Diana Markosian, Carolyn Drake, Jim Goldberg, Alessandra Sanguinetti, Murray Ballard, Gregory Halpern, Jack Latham, Kazuma Obara, Petra Stavast, Dana Lixenberg, Rafal Milach and Alec Soth.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Memory. Place. Identity.

Keep looking...

Tereza Kozinc’s Photographs Are Inspired by the Disapperance of Her Beloved Stenli

Julie Calbert Manipulates Her Images to Experiment with the Photographic Process

Tayla Corney Photographs Philippe, a Man Suffering from Depression

‘Dream the End’ by Dorje De Burgh Is a “semi-imagined mapping” of His Relationship with His Mother

Void x #FotoRoomOPEN — Announcing the Single Images Winner and 12 Shortlisted Photographers in the Series Category

Enter #FotoRoomOPEN and Have a Solo Exhibition at foto forum

There’s a ‘Happy Club’ in One of England’s Most Deprived Regions (Photos by Sandra Mickiewicz)