FotoFirst — William Lakin Portrays the Young Brits Working in Vacation Resorts for the Summer

Premiere your work on FotoRoom! Show us your unpublished project and get featured in FotoFirst.

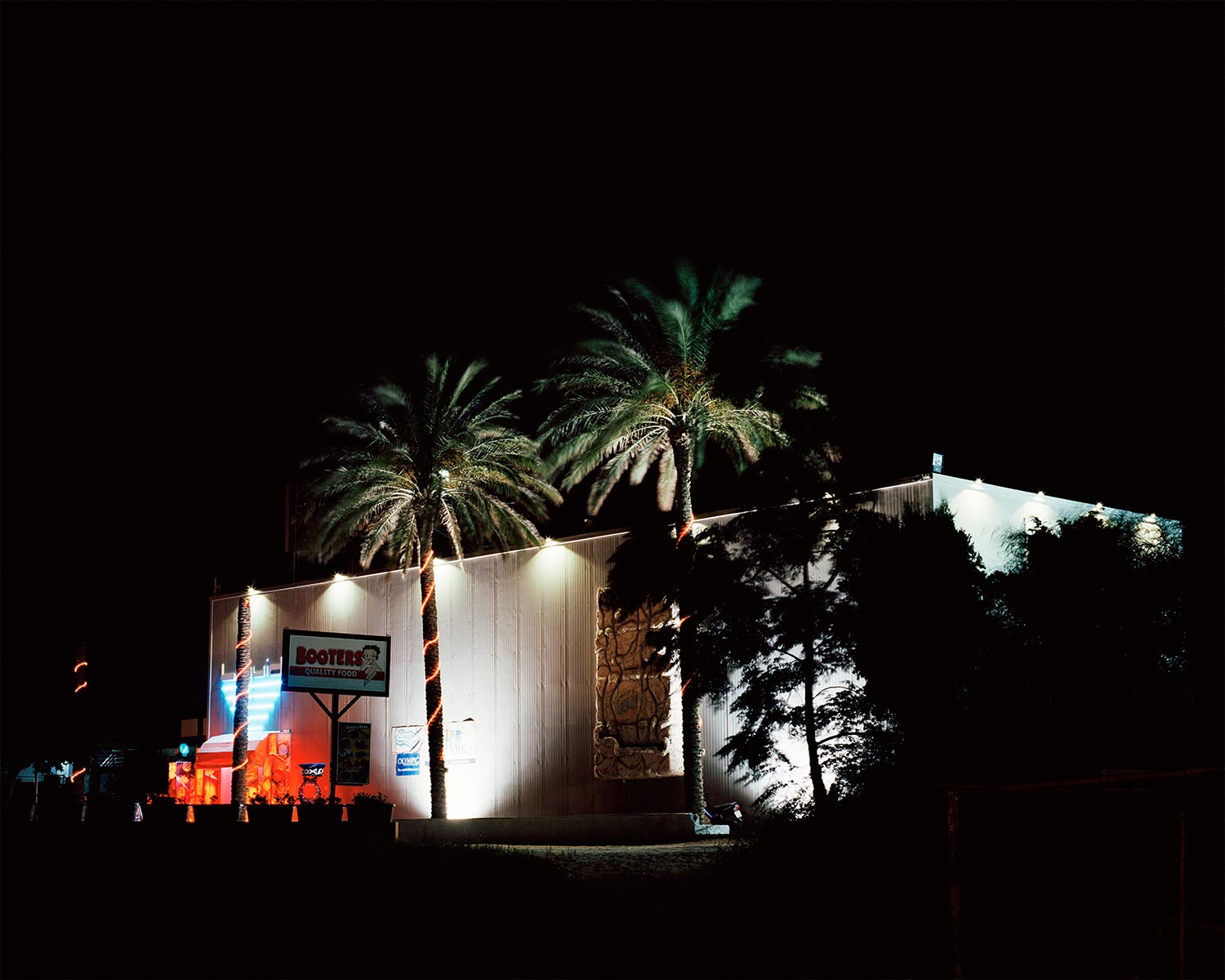

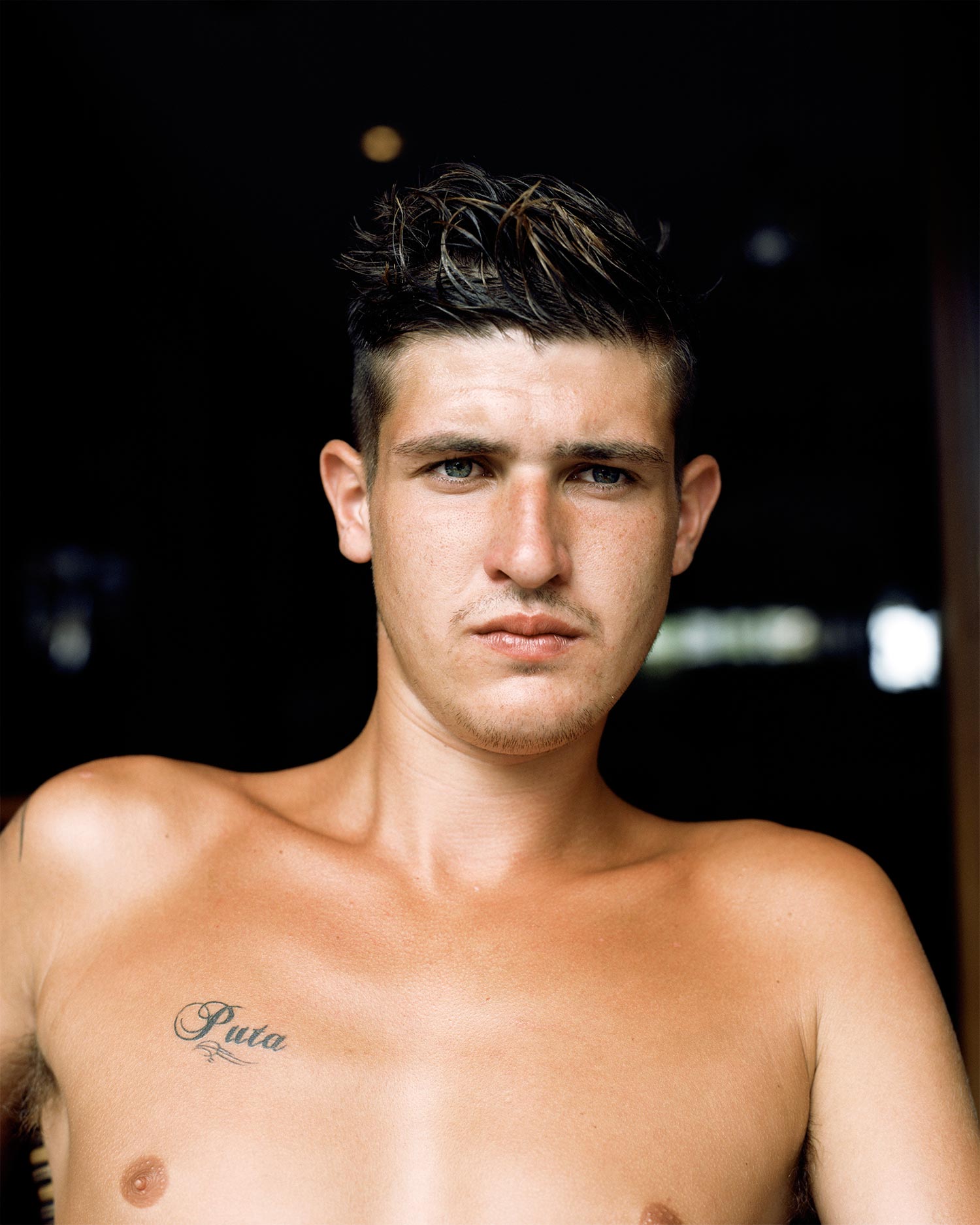

Over the last few years there’s been a tendency—especially in photography—to represent young British people, on vacation to summer destinations across Europe, like wild party animals, spending their nights dancing, drinking uncontrollably and molesting the locals with disrespectful acts. While that may be one part of the story, 25 year-old British photographer William Lakin aims at giving us a deeper insight with Good Times for Free. His subjective reportage offers a more intimate look at the young Brits working in Mediterranean resorts as they take a break from their vacation time and ponder on what the future holds for them.

Hello William, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Thank you for having me! My interests shift quite a lot depending on the kind of project I am working on. It can be quirky contemporary behaviors like in the case of Good Times for Free, or how people respond to social and political pressures.

Please introduce us to Good Times for Free.

Good Times for Free looks at the unusual and adventurous behavior of young British people flying off to holiday resorts in the Mediterranean to work for the summer. I’ve been working on this series for the last four years, photographing in four different resorts.

The project was inspired by my experience as a teenager going on a vacation with friends to a resort where excessive drinking and partying were the main highlights. I did enjoy the vacation but found it quite intimidating: the other male tourists were older, bigger, generally more boisterous and the girls wouldn’t give a skinny 18 year-old like myself a second glance. Despite feeling well out of my depth, I was fascinated by the place and returned to a different but very similar resort the following year, this time to take pictures.

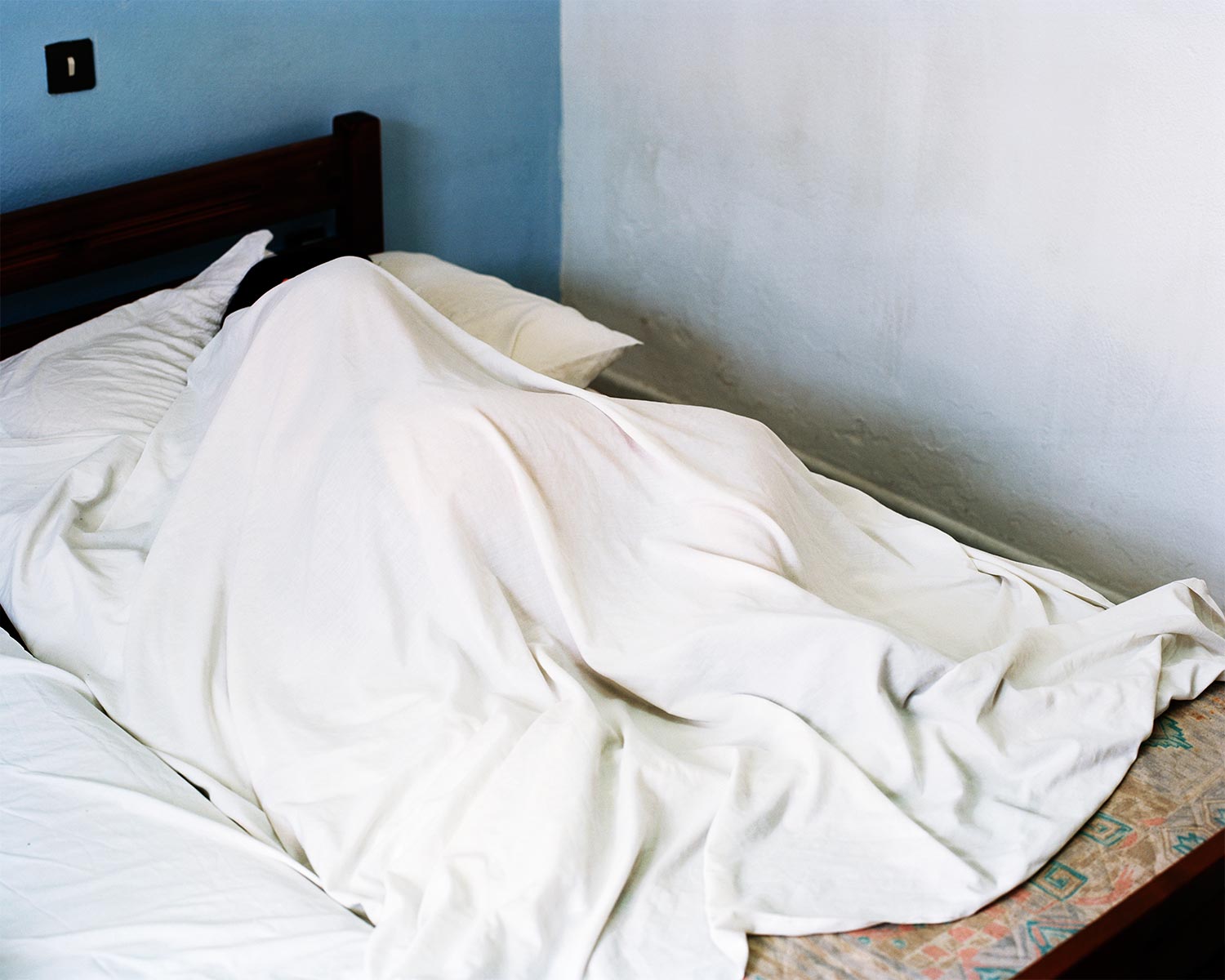

Good Times for Free is about the contrast between the expectations one has about these places and actually experiencing them. Young Brits go to such resorts looking for their version of paradise—to some extent, they find it. But for myself and for everyone I encountered on my trips, it was clear that, no matter how good a time we were having, we had low points too—moments at which you question your own choices, sit and think of home, and wonder what you are doing with your life. This is what I wanted to communicate through the project: the indulgent, hedonistic experience of the night and the harsh, sobering reality of the morning after.

Good Times for Free started as a commissioned work for Hunger Magazine. Why did you decide to develop it into a personal work?

It began as a commissioned piece but I had been thinking about it for a few years before I got that commission. The magazine gave it to me as an open brief; they wanted a documentary essay along the theme of ‘British Takeover’, and I realized it was a good excuse to begin the project.

Despite the premises of Good Times for Free, the pictures (and especially the portraits) give a sense of thoughtfulness rather than carefree times. Can you describe your approach to the work? What did you want to capture in your photographs?

I wanted the portraits to project a sense of reflection for a couple of reasons. For starters, I wanted to present my subjects in a more three-dimensional way, as opposed to the almost barbaric and animalistic way British workers have been represented in TV documentaries and the mainstream media. Another reason was to emphasize the fact that these people are often at a crossroads in their lives: like many in their late teens or early twenties they are looking for answers, trying out new things and ultimately running away from their lives at home, albeit temporarily.

When I photographed my subjects I asked them about their home lives, whether they had left a job to come to the resorts, if they were studying, etc. In most cases it quickly became clear that this was the first time in a while that they were thinking about these kinds of things. People often come to these places to work alone or in pairs, so to some extent they can build a new persona and be who ever they want to be. Having these kinds of conversations often broke that persona down for a few moments and forced them to contemplate.

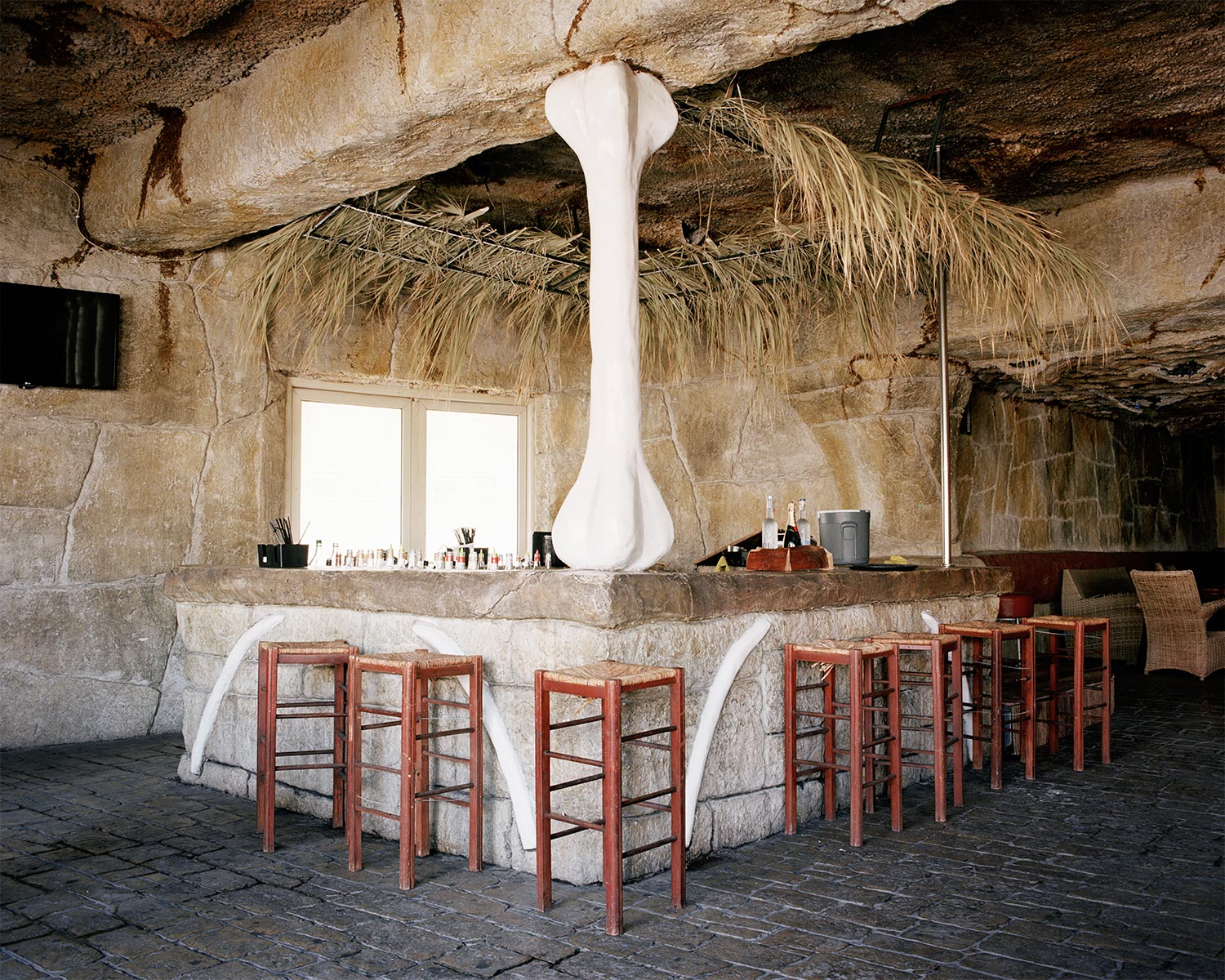

The landscapes and still lifes in the series are there to juxtapose this and point a finger at the absurdity and artificiality of these places.

You have a special eye for portraiture. What’s your typical mindset and process for making a portrait?

It is very different every time. In terms of choosing a subject, sometimes I’m looking for an archetype, at other times someone unusual and surprising catches my attention. My approach also changes for every new portrait. I quite like making people feel awkward when I am photographing them, so I often try to say as little as possible: I think this can make for an interesting portrait as it makes the subject feel self-conscious and appear vulnerable, which is more relatable than someone projecting confidence. It doesn’t always work though—some people just freeze and look like a statue. I find it hardest taking pictures of people who have been photographed a lot in the past or have a very solid idea of their own self-image because what they want to project often looks forced and silly, which can be very difficult to break down.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Good Times for Free?

There are photographers who have made work along similar lines that I admire a lot, such as Gareth McConnell and Ewan Spencer for example; but nothing that I really considered a direct source of inspiration. The representation of places like these resorts have always been very polarizing, so in that respect I knew exactly what I didn’t want to do; but overall I did very little research for Good Times for Free other than having a look at the resorts thought Google StreetView beforehand. I just turned up with a list of things I was looking for and went from there.

How do you hope viewers react to Good Times for Free, ideally?

I hope they spend time reading the images closely rather than just taking a quick, superficial look. My concern for Good Times fro Free has always been that people look at the images, see a load of pictures of ludicrous landscapes and questionable interior design, and pass it off as some kind of effort to shock and amuse—in fact, I chose to photograph some things for what they represent. A poster of James Dean and Marilyn Monroe over a makeshift double bed, one side obviously vacant; or a bar being held up with a giant fake bone: I don’t think things like these need a great deal of explanation. It’s easy to overlook certain nuances when there’s a lighter with plastic tits staring you in the face.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Mostly just non-photography related normal life experiences, which I am aware is a very boring answer. When I first graduated university I spent a lot of time trying to think of projects I could do, and every idea felt overwhelming or lacked the ability to hold my attention for an extended period of time. This gradually led me to realize that unless you are emotionally invested in something or have a real passion for, it you will probably struggle to make interesting and meaningful work about it.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

I am a big fan of Roe Ethridge and how he manages to interweave his art and commercial practice so well. I also admire Paul Graham and his constantly evolving approach, always finding an aesthetic appropriate to his ideas and not the other way around.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Constantly. Evolving. Narrative.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025