FotoFirst — The U.S. / Canada Border Is Not as Undefended as It Looks

IN THIS INTERVIEW > 35 year-old Canadian photographer Andreas Rutkauskas introduces us to Borderline, a work of landscape photography that takes us along the seemingly undefended U.S. / Canada border.

The work will be exhibited for the first time in a solo show at FOFA Gallery in Montreal, Canada from next 29 February (more details here).

Hello Andreas, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

My pleasure, I always find it important to discuss one’s projects. My work is mainly focused on landscape, in particular Canadian landscapes that have been affected by technology. This may refer to physical alterations in an anthropocentric sense, or the psychological alteration of one’s relationship to a landscape due to technological developments. As examples, my recent projects have addressed the cycles of industrialization and deindustrialization in Canada’s oil patch (Petrolia, 2013), the impact of Internet-based research on wilderness recreation (Virtually There, 2010-15), and the subtle technologies used to survey the Canada/US border, which is the project that we will be discussing here.

Please introduce us to Borderline.

Borderline grew out of an invitation to participate in a 2011 group exhibition titled Projet Stanstead ou comment traverser la frontière, curated by Geneviève Chevalier. The show was important for my consideration of how the boundary between Canada and the United States of America fit in amongst international border lines, and soon after I decided to begin photographing various idiosyncratic sites across the entire border.

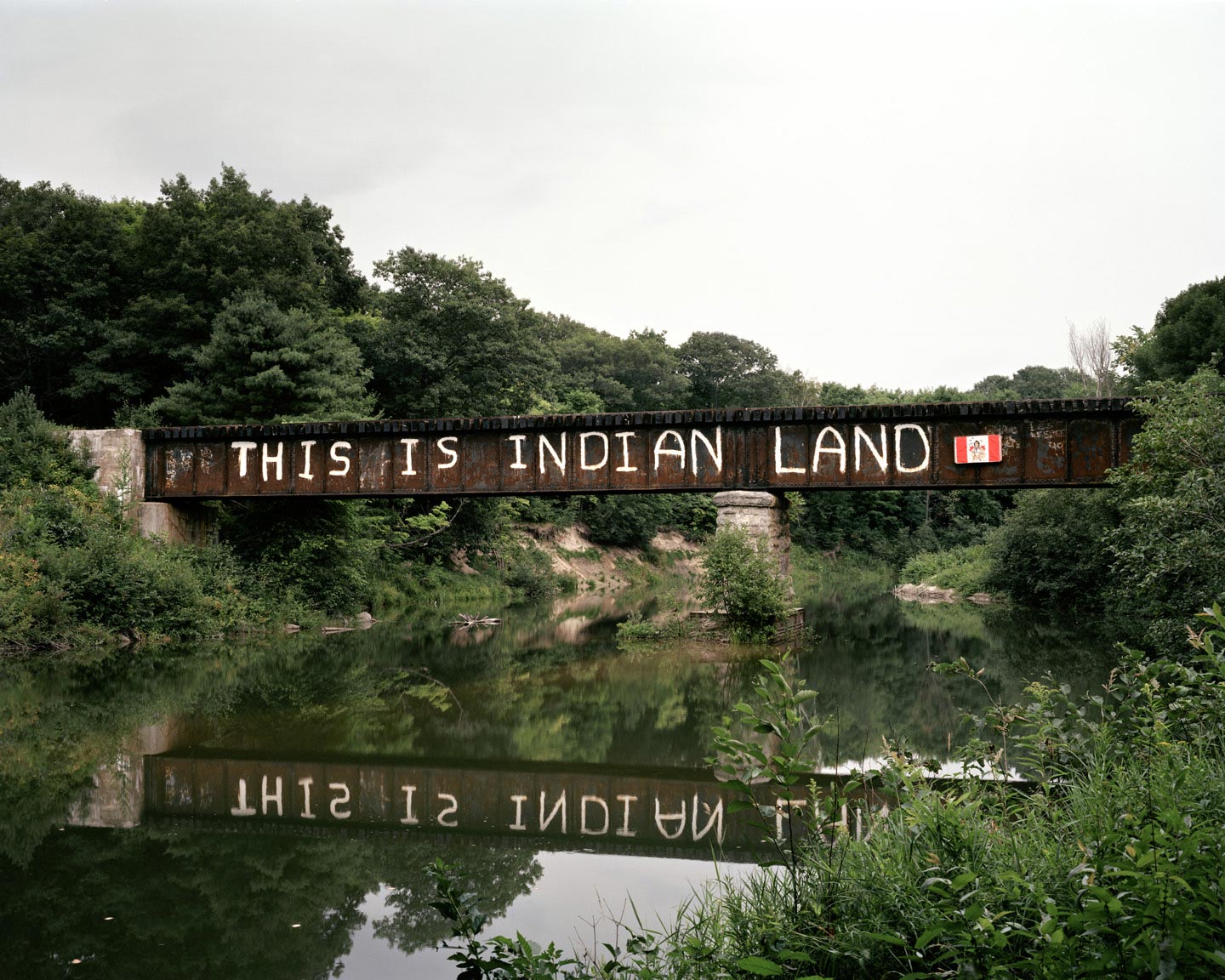

As the project began to take shape, I focused on closed crossing points and the more remote areas of the border, photographing in color, as opposed to the initial black & white images, with my 4×5” camera. Following the attacks on the World Trade Center in September of 2001, policies surrounding migration and day to day traffic along the border changed dramatically. The Québec town of Stanstead is one poignant example, where architecture and infrastructure straddle the boundary; but there are many more complexities along the divide, including the U.S. enclaves of Northwest Angle and Point Roberts, 0 Avenue in British Columbia / Washington State (a roadway acting as the de facto boundary), and a number of First Nations territories that are considered sovereign regions independent of both Canada and the United States. It was my intention to create work about these sites.

In your pictures we see no customs stops, no barriers of any kind, and no militaries – it looks like you could easily cross to the other side and get away with it. Is it in fact so?

The photographs in Borderline set up a bucolic landscape that is typical of the North American frontier. They stand in contrast to our collective imagination surrounding the term ‘border’, which conjures up imagery of more heavily militarized zones of separation such as Israel’s Green Line, the Indo-Pakistani Line of Control, or the Korean Demilitarized Zone.

But it isn’t as uncontrolled as it looks. While the Canada / U.S. border is often referred to as ‘undefended’, it is through technological advancements in surveillance that the boundary is monitored. My project features images of certain locations where official crossing points used to exist, however they have now been barricaded, sometimes in very primitive ways. While the pictures do not depict U.S. Border Patrol vehicles and agents, or those of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), many of the photographs were preceded by encounters with these officials. Both the Canadian and U.S. governments utilize CCTV and thermal imaging cameras to scrutinize the border. Additionally, ground sensors are embedded under those roadways leading to dead ends, providing situational awareness for Border Patrol and RCMP. Often within five minutes of my arrival at these locations, and sometimes even prior to my arrival, a field unit would be dispatched to investigate. I never intended for my project to involve portraiture, but I did ask the field units if they would be willing to be photographed. The response was a unanimous no. After explaining myself to the officials, they would back their vehicles out of my frame, and I would take the shot.

This process however is only part of what leads to the appearance of the border being so porous in my work. There are of course many places where I did not encounter anyone, where I could walk for hours along the denuded cutline that separates the two countries without impediment. The borderlands between Canada and the U.S. are a zone where humans are discouraged from lingering, but ultimately this is part of a vast territory – nearly 9,000 kilometres – that is impossible to fully control.

With the rise of the immigration fluxes, especially in Europe, the border is becoming topical again in problematic ways. What do you think a border should be?

I suppose my best answer would be that a border should be capable of adapting to changing circumstances. To quote from the often cited Robert Frost poem Mending Wall, I am not of the opinion that “good fences make good neighbours”. Take for example the border walls between the United States and Mexico. These fortifications have not stopped, or many would argue, even slowed, illegal immigration and the transit of narcotics and weapons from one country to the other. It has in a very quantifiable way however increased casualties for those attempting to circumvent it, as migrants are forced into more remote and treacherous terrain in their attempt at seeking a better life.

If we look at the world’s most heavily fortified border walls, there exists a dramatic discrepancy in social class, or dominant religious belief between the adjacent nations, which drives the dynamic of their borderlands. The Canada / U.S. border is quite different in this regard, since the neighbouring nations are relatively similar in economic status and political ideology (with an emphasis on the term ‘relatively’). Some political scientists have argued that Canada itself is a borderlands nation, honing in on the fact that we take many of our cultural cues from our more populated neighbour to the south. I am not suggesting that this makes our border ‘better’, but it eliminates certain motivations to bolster security. With continued globalization, it would be the diminishing of economic disparity between nations and the sharing of resources that would make for better borders.

Is there anything that particularly impressed you about the US-Canada border?

It sounds obvious, but its length. 8,891 kilometres is one thing on paper, but it is another thing to traverse this geography. The diversity of the terrain is quite incredible, as are the cultures and populations along it. Juxtapose for example the boundary between Detroit, Michigan (the largest city on the border, with a metropolitan population of around 4 million) and Windsor, Ontario (around 300,000 people reside in its metropolitan area), with that of Snowflake, Manitoba (population 2) and Hannah, North Dakota (population 15).

Maintaining protocol among these two radically different population densities can be challenging. When crossing at a busy port of entry, one is treated as just another number, however when I made a photograph at the Snowflake/Hannah crossing, all of the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) officials, and the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents came out to greet me and discuss my project for nearly one hour. I experienced discrepancies in behaviour in other situations as well, for example on occasion I was interrogated by CBP agents at the port of entry, or accused of illegally crossing into the United States by Border Patrol. Yet at other times, Border Patrol agents provided me with tips on where to make good photographs, and RCMP gave me their personal numbers to call in order to alleviate suspicion on my future visits.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on this series?

First and foremost I would like to thank Geneviève Chevalier for planting the seed for this project. Visually speaking, Kai Wiedenhofer’s book Confrontier, Donovan Wylie’s The Maze, and Simon Norfolk’s images of the U.S. / Mexico border informed my aesthetic approach for Borderline. I also took textual inspiration from James Laxer’s The Border, Derek Lundy’s Borderlands, and Matthew Farfan’s writings in particular The Vermont-Québec Border: Life on the Line.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

First hand experience in the landscape has continued to be the single most important element. One thing leads to another, so despite owing gratitude to online research tools such as Google Earth, Maps, and Street View, they are only capable of revealing so much of what one may experience in a given place. ‘The map is not the territory’, and thankfully so. Extended projects such as Borderline have taught me not to disregard a location based on preliminary research. You never know what you might discover in the field.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

A few photographers making work today that I respect are Olivo Barbieri, Scott Connaroe, Luc Delahaye, Stan Douglas, Mitch Epstein, Geert Goiris, Jan Kempenaers, Thomas Kneubühler, Richard Misrach, Richard Mosse, Taryn Simon, and Hiroshi Sugimoto. I also admire the following artists, and not necessarily for their photographs: Francis Alÿs, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Olafur Eliasson, Omer Fast, Trevor Paglen, Ed Ruscha, and Charles Stankievech.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Landscape. Technology. Change.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024