Devin Lunsford’s Landscape Photographs Are Inspired by Southern Gothic Literature

30 year-old American photographer Devin Lunsford introduces his landscape photography series All the Place You’ve Got as a project that “explores notions of beauty, anxiety, and the passage of time while documenting the changing landscape along Alabama’s Corridor X. Begun nearly 50 years ago, the newly completed interstate project connects Birmingham to Memphis through a once-remote part of northwest Alabama populated by desolate towns and shuttered coal mines. The project expresses my search for meaning within a place where I am both inhabitant and outsider, so I photograph as a means to understand who I am and where I come from while using my camera to make quiet, melancholic pictures that capture beauty in the marginalized and mundane. These southern gothic landscapes contrast liminal, isolated spots with verdured spaces full of lush color that provide points from which to consider the complex economic, ecological, and social histories of a place in flux.”

Devin’s initial inspiration for All the Place You’ve Got was “simply a desire to not be where I was at that time. I was in a very stuck place both creatively and emotionally at the initial start of the project, way before I even knew it would become a project per se. What I discovered was that I needed to get out of the areas that I had grown accustomed to. I believe it was Robert Adams who said the best way to start a project is to go for a walk, so I applied that mentality to my car and I would drive for hours, literally every single day. I knew Corridor X would be a good place to start from a photo expedition a buddy of mine took me on some years back to photograph the steam plant out there, before the interstate was completed.”

Years later, Devin revisited that interstate and started taking every exit and visiting every town they led to. “What I noticed was a distinct feel of otherness, especially in comparison to Birmingham which within the last few years has been going through its own “revitalization” and search for identity. These towns and locations felt from another time and were completely at odds with both the newly completed interstate and the revitalization happening down the road. There’s a fine line there that straddles between natural beauty, nostalgia, and desolation which I found deeply compelling, and one that I felt mimicked my emotional state of the time. I wanted the project to not only be about the reality of these locales but also a self-portrait of sorts, as these were the places I felt connected to. Not as a consequence of personal history but because of their ability to bring out something creative in me that honestly had not been tapped before. It brought out a huge respect for the deep South, not necessarily ideologically, but because of its complexity and its ability to survive on the fringe. These places contain a brute form of honesty, they are what they are, and neither the place nor the people in it truly give a damn about what anyone thinks. It’s hard for me not to have a bit of reverence for that.”

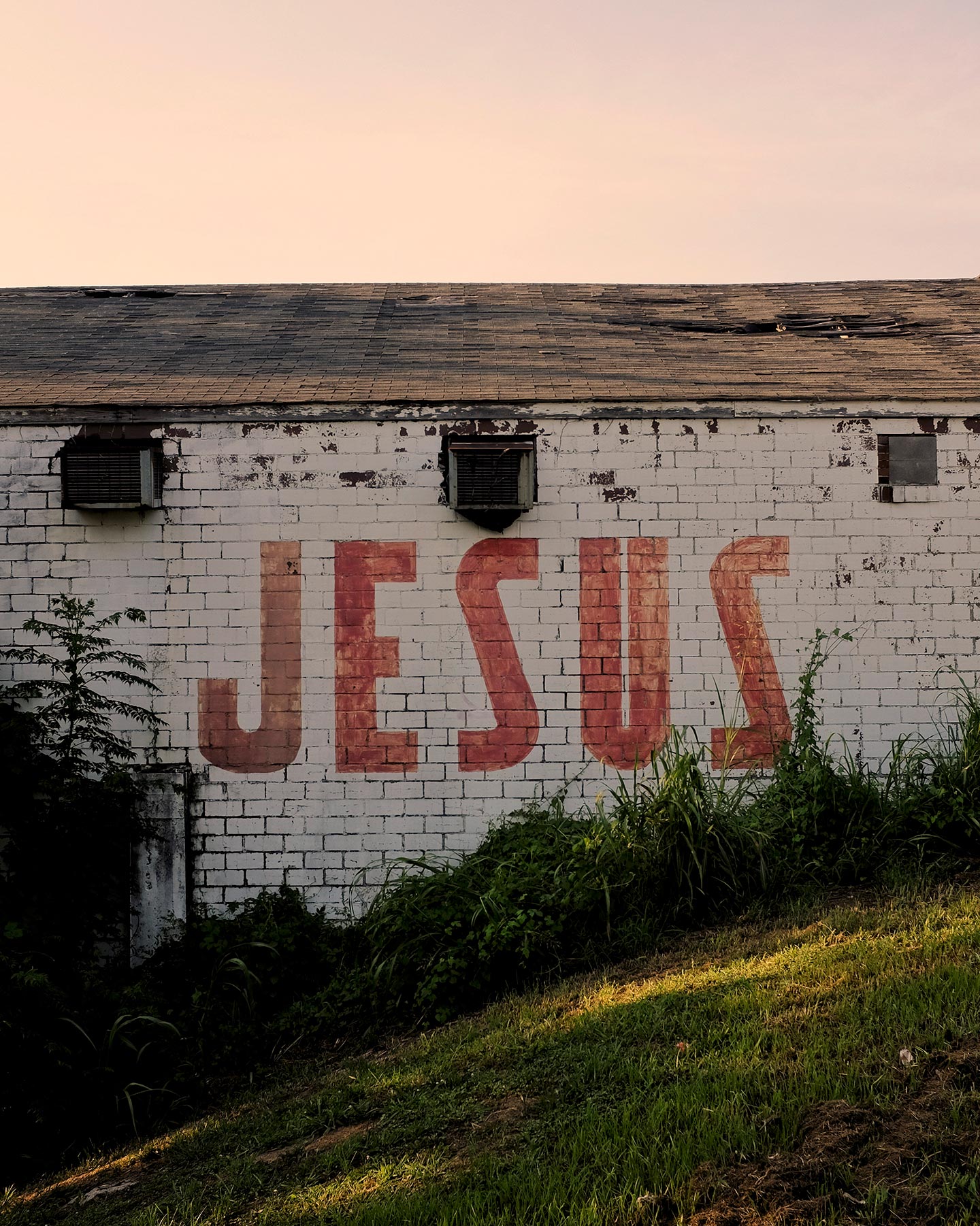

In his images, Devin was aiming to “find a balance between the sublime and the decrepit while maintaining an almost post-rapture feel to the images. It was impossible for me to ignore the religious influence on the South, and the notion of rapture has always been of interest to me, so I purposefully tried to include as little people as possible with the exception being a few obscured self-portraits and a lone figure under a disregarded shopping center sign. I was very drawn to utilizing bold color not only to highlight the beauty that exists naturally in the area but also to juxtapose the harsh and forgotten man-made structures littered throughout.”

Southern Gothic literature was Devin’s major source of inspiration for All the Place You’ve Got: “I leaned heavily into the common tropes of the genre. The title of the series is taken directly from a Flannery O’Connor quote from the novel Wise Blood which states: “Nothing outside you can give you any place. You needn’t look at the sky because it’s not going to open up and show no place behind it. You needn’t to search for any hole in the ground to look through into somewhere else. You can’t go neither forwards nor backwards into your daddy’s time nor your children’s if you have them. In yourself right now is all the place you’ve got.” That quote connected with me severely as I was making this project and thinking about my own connection—and at times disconnection—to the South as a place. I also felt it important to keep previous work made in Alabama fresh in my mind: Walker Evans and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men as well as the artwork of William Christenberry were certainly a source of inspiration. Finally, music was a huge factor on the long drives—albums by Kurt Vile, Hank Williams, Cass McCombs, Elliott Smith, The Mountain Goats, Slowdive, Grails, and Car Seat Headrest were all frequent players, although there were certainly more.”

Devin’s main interest as a photographer lies is “capturing the alien within the intimate minutia of place and time. Seeing and photographing the outer limits of a given area and venturing into spaces many would typically overlook is a huge joy for me and plays into my own personal interests of exploration and at times my need for seclusion. Photography is such a cathartic release for me that sometimes I feel like I am chasing a bit of a high that comes from that release.”

Some of his favorite contemporary photographers are Bryan Schutmaat, Cody Cobb, Jared Ragland, Matt Shallenberger, Jenny Fine, Stacy Kranitz, Alec Soth, Aaron Canipe, Allison Beondé, Adam Bellefeuil, Tatum Shaw, McNair Evans, Ian Van Coller, Daniel Shea, Justin James Reed, Todd Hido, Matt Eich, Gregory Halpern, Paul Bobko, Reuben Wu, Monty Kaplan, Zora J Murff and Nick Mehedin. The last photobooks he bought were The Leaping Place by Matthew Shallenberger and Good Goddamn by Bryan Schutmaat.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography:

Create. A. Potential.

Keep looking...

Stonetown Diary — Jenny Hueston’s Lyrical Images Capture Life in Her Small Hometown

42 Wayne — Jillian Freyer Has Her Mother and Sisters Perform for the Camera

Catherine Hyland Captures the Touristification of China’s Barren Natural Landscapes

Ten Female Photographers You Should Know — 2020 Edition

FotoFirst — In Love and Anguish, Kristina Borinskaya Looks for the True Meaning of Love

Vincent Desailly’s Photobook The Trap Shows the Communities in Atlanta Where Trap Music Was Born

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2020