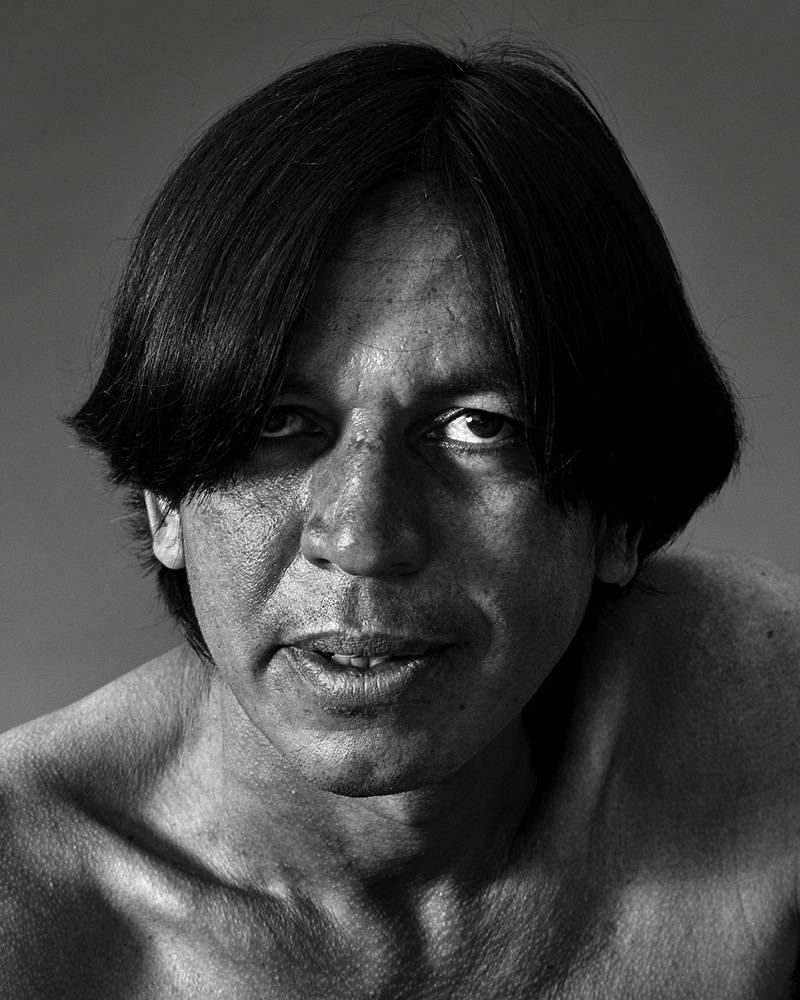

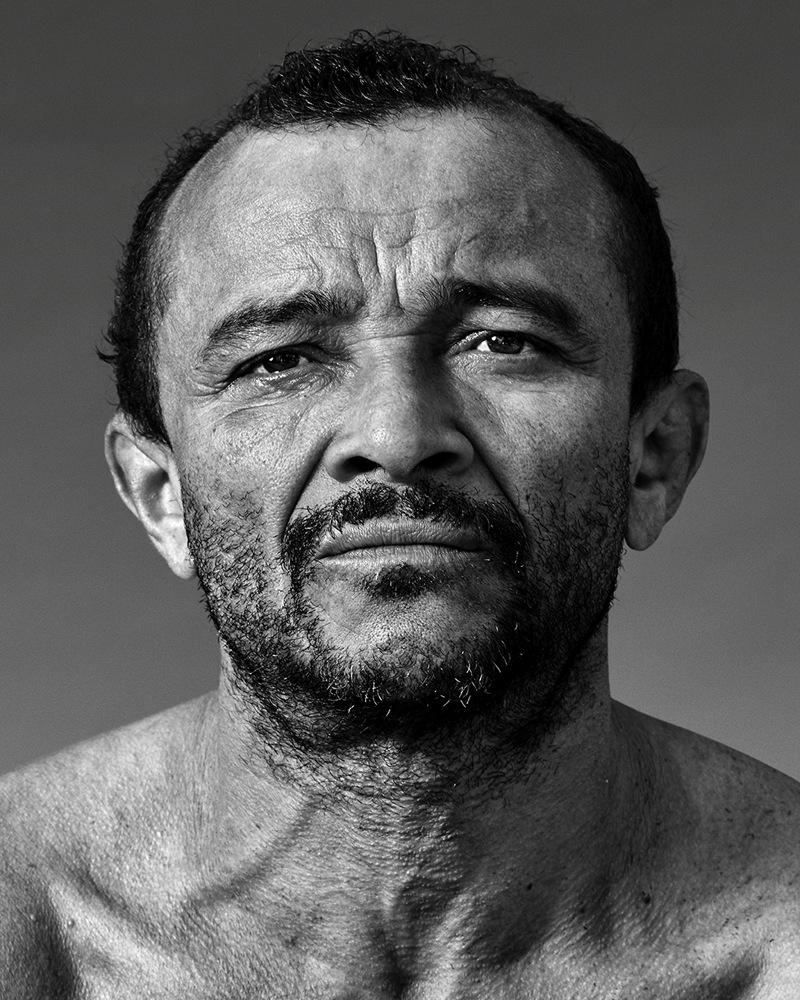

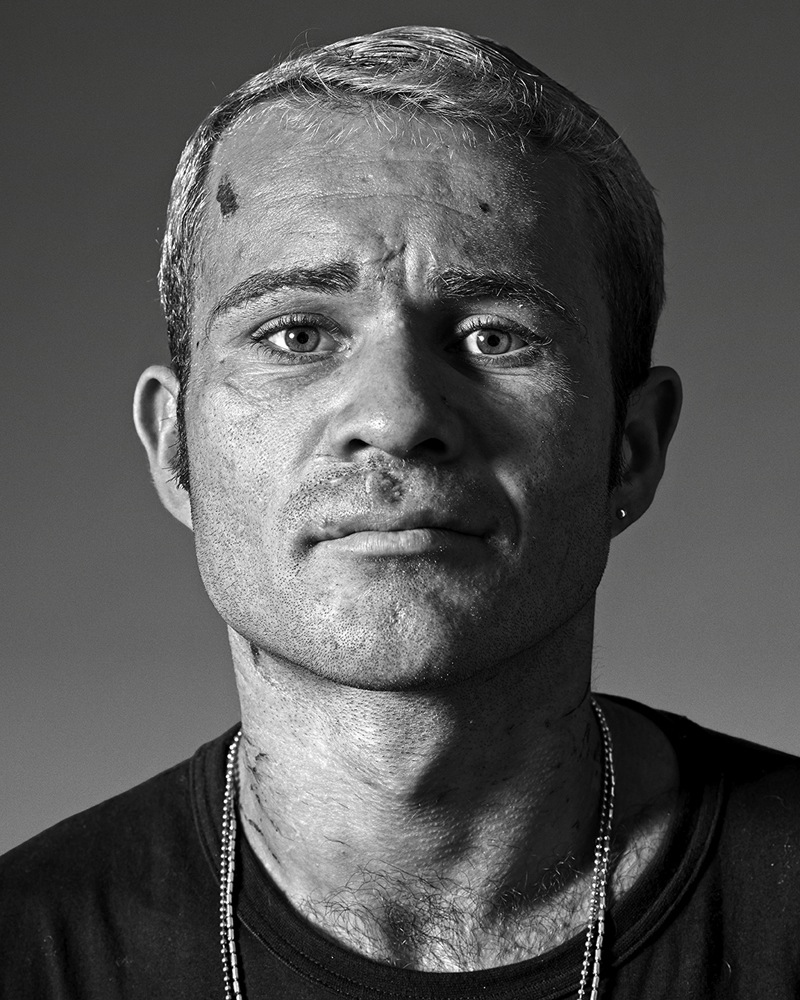

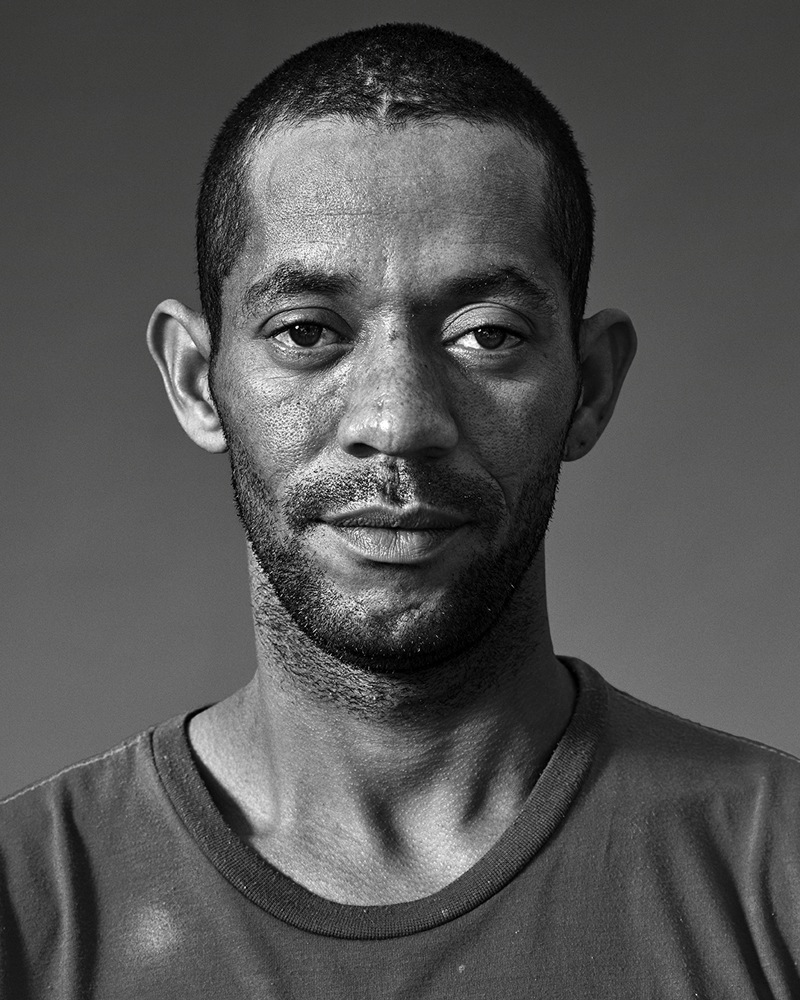

Portraits from Cracolândia

Cracolândia is a district south-west of Sâo Paulo, Brazil, where the largest concentration of the city’s crack cocaine addicts can be found. Crack cocaine addiction throughout Brazil has been spreading at alarming rates, so much so that it has become one of the country’s most pressing social issues, yet another manifestation of the growing inequalities between the rich and the poor.

For his latest work Ghosts, British photographer Sebastian Palmer has recently visited Cracolândia and made a series of powerful portraits of some of its residents right in the district’s streets, with the help of a portable make-shift studio.

Hello Sebastian, thank you for this interview. What have your main interests as a photographer been so far?

No worries, thank you. I have always been interested in a number of different areas. For example, my commercial work ranges from action and sports photography through to product and still lifes, whereas my personal work for the last 3 years has been centered on photographing sections of Brazilian society that have been marginalised and discriminated against (in an attempt to give them a voice).

When and why did you decide to work in Cracolândia?

I have always wanted to shoot this series. As crack addiction is rife in Brazil and many believe that it has reached epidemic proportions, it is naturally a topic that needs to be addressed.

The main factor in shooting it when I did was being able to gain access.

Can you talk a bit about the issue of crack cocaine addiction in Brazil today? What information did you collect while making Ghosts?

According to recent studies Brazil is the world’s largest consumer of crack cocaine with an estimated 1+ million users. Brazil shares a long and largely unmanned border with the top three cocaine producers – Peru, Bolivia and Colombia – allowing the country to be flooded with the drug.

Why did you think black&white portraits was the best way to portray your subjects?

My main aim was to humanise my subjects and I felt that this could best be achieved by minimising any distractions and allowing the viewer to come into direct face to face contact with the sitter – hence the tightly cropped black&white headshots.

How did you choose the subjects of Ghosts? Did you know them before starting the project?

I didn’t really have the luxury of being able to choose who I wanted to shoot. In reality, they chose me.

On initial visits I brought no equipment with me – there was a lot of talking to people, getting to know them, their stories; explaining the project and asking If they would like to be involved.

On shoot days, I set up a mini make-shift studio – one light , one stand and background paper – in an area that everybody could see, which naturally sparked curiosity. People would come over, be inquisitive and after having had a chat and me explaining what the project was about, I shot anyone who felt comfortable in having their picture taken.

Also, If I saw an interesting character I would ask them if they would like to be involved. Sometimes they did, sometimes they didn’t.

You say that last year’s World Football Cup, which was held in Brazil, actually worsened the situation for crack cocaine addicts. How do you mean exactly?

It’s not that the World Cup itself made the situation worse but rather the attention that came with it. For example, the crack problem garnered a lot of attention and the images that accompanied the stories were often taken from far away and with no interaction. I believe such imagery only helped to strengthen the “us” and “them” mentality – reinforcing negative views and prejudices and as a result further dividing an already fractured society.

Can you share the stories of some of the people you photographed?

Wow, there are so many and all of them contain so much heartache and pain I wouldn’t know where to start. For example, though, the teenager you see has been homeless and addicted to crack since the age of 7 (and this isn’t uncommon)… One of the sitters feeds his addiction through armed robberies and car jackings.

From everyone that I spoke to I would hear at least one of the following subjects be mentioned in their story: homeless as a child, physical abuse, sexual abuse, murder, rape, robbery, prostitution, mental illness, loss of family, alcohol addiction, and the list goes on.

Your series about Cracolândia is part of a bigger documentary project about marginalized sections of Brazilian society you’ve been working on for three years. What other topics have you touched on so far, and what is next?

So far I have touched on Prostitution, Transsexuals and People living in Illegal Occupations – squatters, for want of a better word. Currently, I’m in the production stages of the next chapter which will focus on Afro-Brazilian religions. There are many more areas that I want and which need to be covered but as always it comes down to those two little things: time and money.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Experimentation. Interaction. Adventure.

Keep looking...

A Map of of the Dark — Tereza Zelenkova Surveys the Eerie Myths and Legends of Her Homeland

Resistance, Nature and Mysticism: Welcome to the Remote and Fascinating Region of Dersim

Off the Internet, into Real Life — Amy Lombard Photographs the Meetups of Online Communities

Gregory Halpern On His Los Angeles Photos Published in New, Beautiful Photobook ‘ZZYZX’

Neither You Nor I — Yulia Spiridonova Imposes Her Presence in Staged Scenes of Intimacy

Ten Best #FotoMobile Submissions Vol. 56

Inside the Bunker-Turned-Theater Where Visitors Relive the Atrocities of the Soviet Era