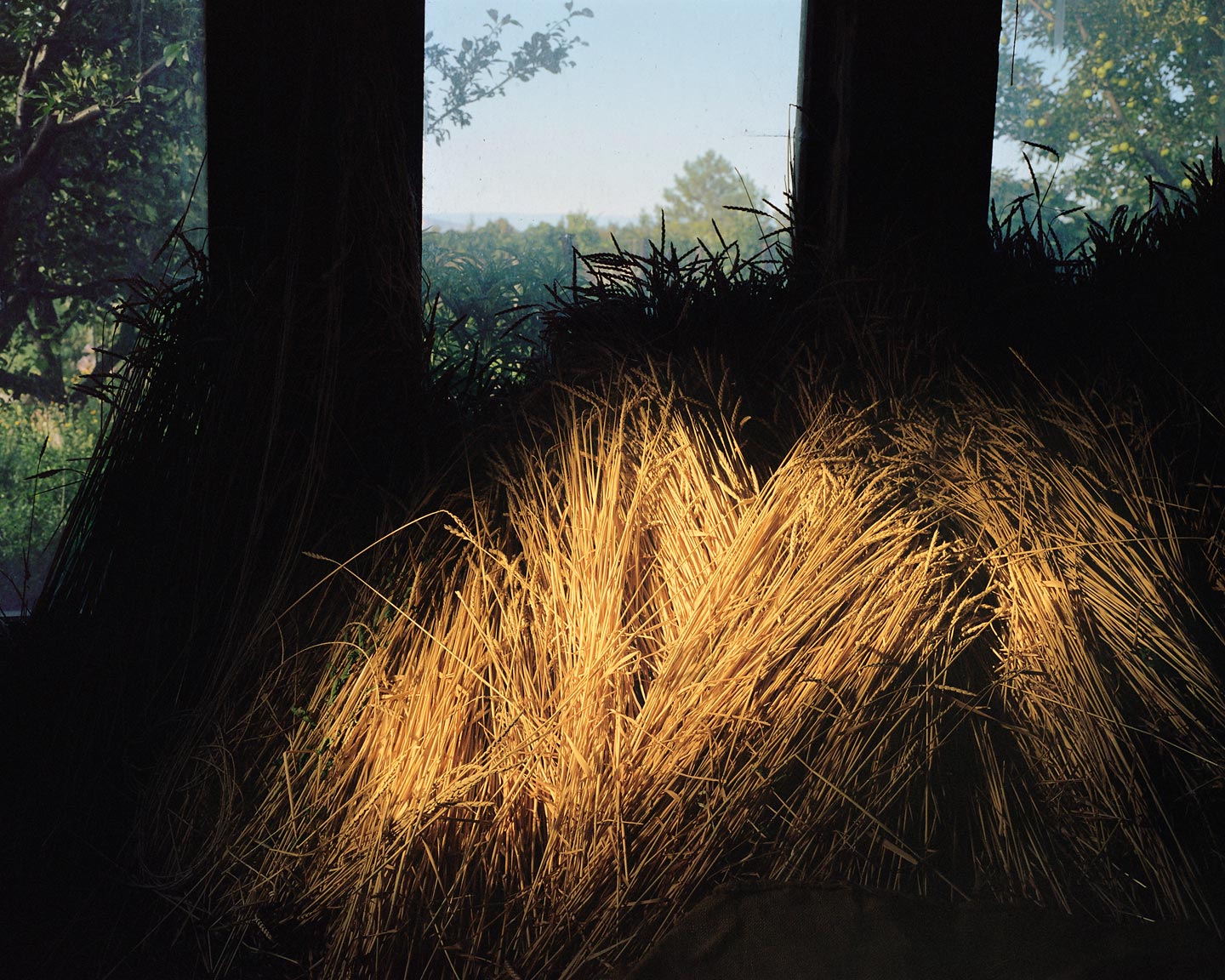

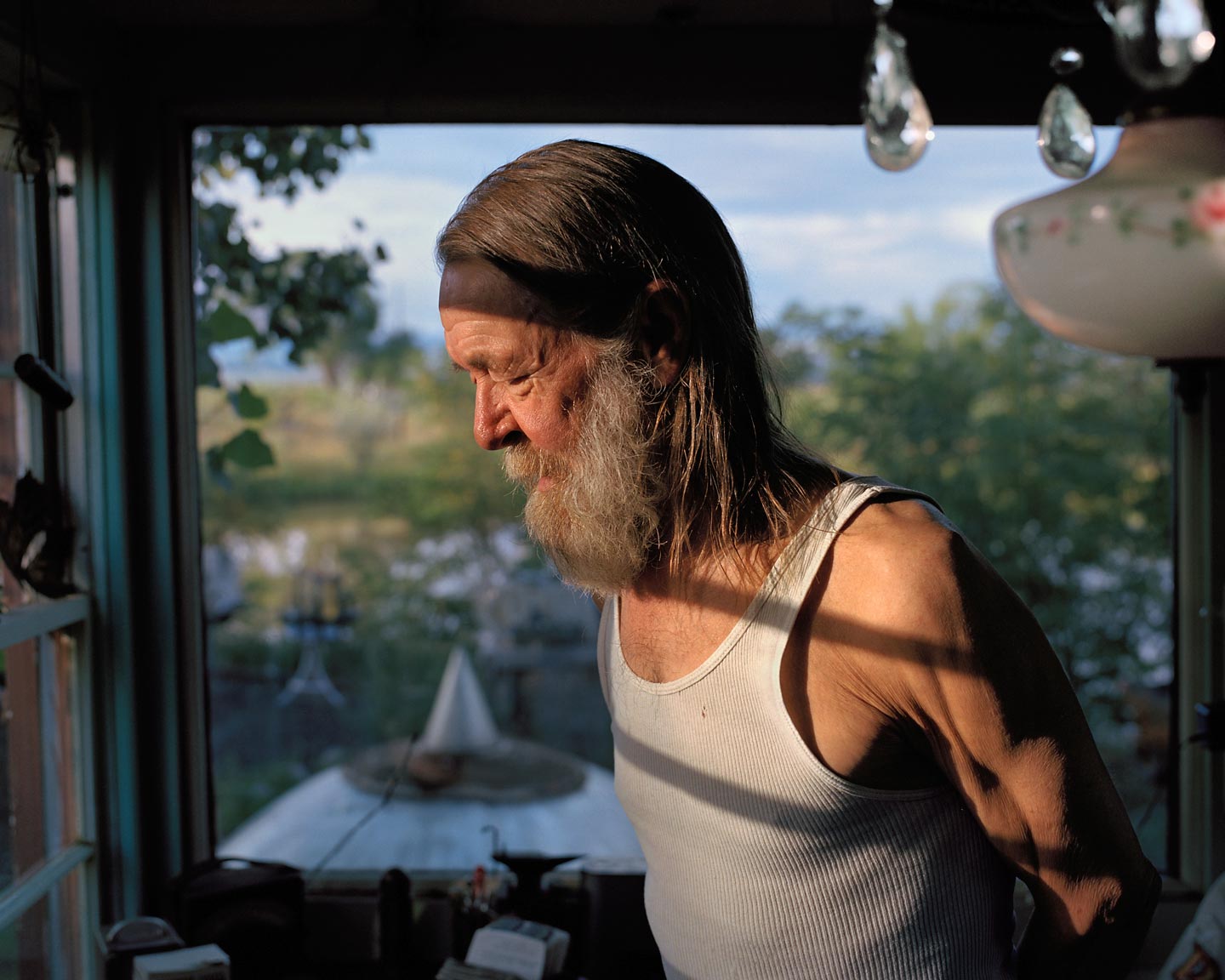

Americana — Trent Davis Bailey Rediscovers the Valley in Colorado He Used to Visit as a Child

The mythical American West and what it looks like today has been the subject of much recent photographic work. With the ongoing series The North Fork, 31 year-old American photographer Trent Davis Bailey adds his contribution to redefining the contemporary American West as filtered by Trent’s personal experience: the project, which we publish as part of our Americana week, is a subjective reportage from the North Fork valley in Colorado where he used to often travel to with his family as a child.

Hello Trent, thank you for this interview. Please tell us a bit about the North Fork Valley: what kind of place is it?

The North Fork is both a place in my imagination and a remote river valley in my home state of Colorado. It is a farmland sheltered by deep wilderness, precipitous canyons, sloping forests, and ragged peaks. Forests of pine and thick aspen woodlands shroud its mountain passes. The rest of the elevated land is dotted with sagebrush, scrub oak, and juniper trees. The North Fork itself brings to mind the mythological Western landscapes of America’s collective imagination. These are the wide-open vistas of cowboy folklore, manifest destiny, and romantic art and literature. These are the landscapes upon which Westerners have directed their hopes, dreams, and ambitions, and redirected their disappointments.

Why did you decide to create a body of work about the North Fork Valley?

I had visited the valley when I was seven years old and I was enamored with the landscape, the community, and the food that was grown there. I had seven cousins who lived just outside the town of Paonia with my aunt and uncle in a large rectangular army tent. They lived off the grid and grew their own food, but they weren’t isolated: they were an integral part of the local community. I found the wildness of my cousins’ world to be much more enticing than the suburbs of Denver, where I lived with my dad and my brothers. Unfortunately, my dad and my uncle had a falling out a few years later, which extricated our families. Disappointingly, I no longer visited the North Fork as a child. Twenty years later, though, I decided to return. Since then, photography has allowed me to deal with those memories in a visceral way.

What was your main intent in creating this body of work?

My intent has been to respond to my childhood memories: to look at rural land, labor, community, and food production, all while on this search for a familial connection.

Can you talk a bit about your approach to The North Fork, and what kind of images you were looking for?

Like anyone who has a stake in a landscape, I have been curious about what kind of life is possible in the North Fork. By making return trips for the past five years, I have been able to observe the valley’s temperament throughout the seasons and slowly establish relationships. Bit by bit, photography has helped me become more intimate with the valley and the locals who live there.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on The North Fork?

Yes. The photographer Robert Adams’ essay Truth in Landscape comes to mind. In this essay, Adams suggests landscape pictures offer us “three verities — geography, autobiography, and metaphor.” For Adams, “Geography is, if taken alone, sometimes boring; autobiography is frequently trivial; and metaphor can be dubious. But taken together… the three kinds of information strengthen each other and reinforce what we all work to keep intact—an affection for life.” While my pictures from the North Fork extend beyond the realm of landscape, Adams’ three verities have been, for me, a guide to explore the various influences of this project.

How do you hope viewers will react to The North Fork, ideally?

I hope these pictures allow each viewer to imagine their own North Fork and react to a rural way of life in America and an ecology that I value.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

I’ll start by saying that, as an artist, it’s important to know the lineage of artists who have come before you. It’s also true that looking at too much photography can be detrimental. In my first year of graduate school, one of my advisors, Abner Nolan, recommended that I take a break from looking at photographs. Instead, he suggested I watch more films and read more literature. Based on the work I was making in Colorado, he pointed me towards Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy, David Lynch’s Lost Highway, and Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, all of which are character-driven stories of enchantment and ambiguity in the American West. All three gave me photographic ideas for experimenting with storytelling and inspired me to loosen up any preexisting narratives in my work. Of course, the locals in the North Fork community have influenced me greatly as well.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

If this answer is any indication of whose work I admire, some recent photobooks I’ve acquired are Latoya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family, Alex Webb’s La Calle, and Aspen Mays’ and Dan Boardman’s Where We’ve Been, Where We’re Going, Why?

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Intuition. Identity. Archive.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025