Lux — Christina Seely Photographs the Cities of Blinding Lights

39 year-old American photographer Christina Seely speaks about Lux, a series of cityscapes shot at night in several cities of the United States, Western Europe and Japan. By capturing the abundance of artificial lights emitted by the cities, Christina invites a reflection on how humans have transformed the natural environment.

Lux is available as a photobook recently co-published by Radius Books and the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago – buy your copy here.

Hello Christina, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I am interested in human understandings of time and the natural world and in exploring the inter-relationships between built and natural global systems. The growing complexity of image-based media and visual culture have a big influence on the evolution of my work and research track.

What is Lux about, in particular?

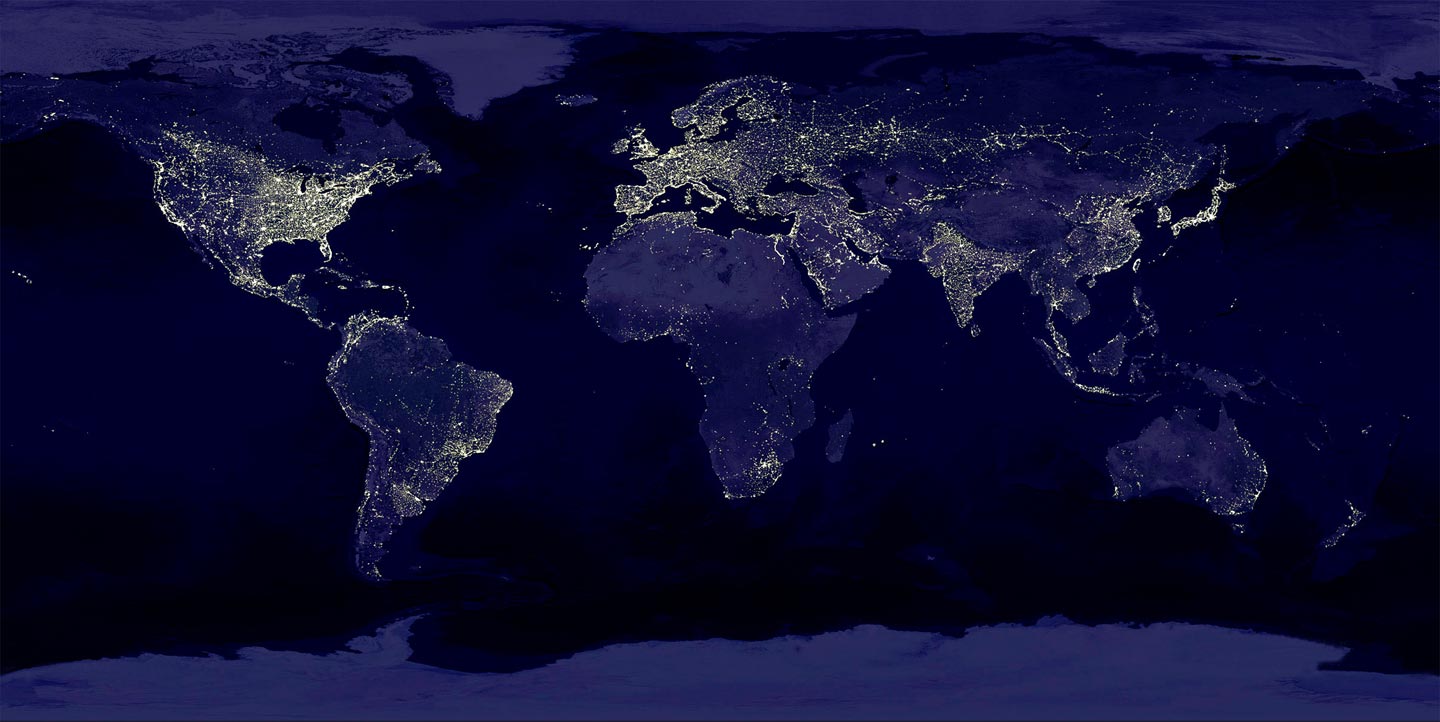

For millions of years only dramatic shifts in terrain informed the reading of the earth’s surface from space. The cumulative light from highly urbanized areas now creates a new type of information and understanding of the world that reflects human’s dominance over the planet. Lux, which is titled after the system unit for measuring illumination, is made up of photographic portraits of man-made light emanating from cities within the most brightly illuminated regions on the NASA map of the night earth.

Using this map (composited in 2002) as reference, Lux focuses on cities in the United States, Western Europe and Japan. These economically and politically powerful regions not only have the greatest impact on the night sky but this brightness reflects a dominant cumulative impact on the planet. Collectively these regions emit approximately half of the world’s CO2 and (now along with China in its state of rapid expansion) act as the top consumers of electricity, energy and resources.

How did you get the idea for this project, and what are you trying to communicate with these images?

I’ve long had an interest in trying to deconstruct the larger systems we depend on in my work, and to generate in some way a connection between the individual/viewer and the entirety of a system. In 2005 I rediscovered the NASA map of the world at night. I was captivated by the beauty of the light on the map and the complexity of what this light represents about us, both collectively and as individuals. This light visually dominates the map with its intense contrast to the darkness of the land and water, and also looks a lot like bacteria spreading. The relationship of light as both information on the map and information building on a negative was also an interesting analogy. The combination of these things lead me to want to create a project about this light.

The Lux pictures are all captioned ‘Metropolis’ plus the coordinates of the city seen in the picture. Why did you decide to keep out the name of the cities you photographed?

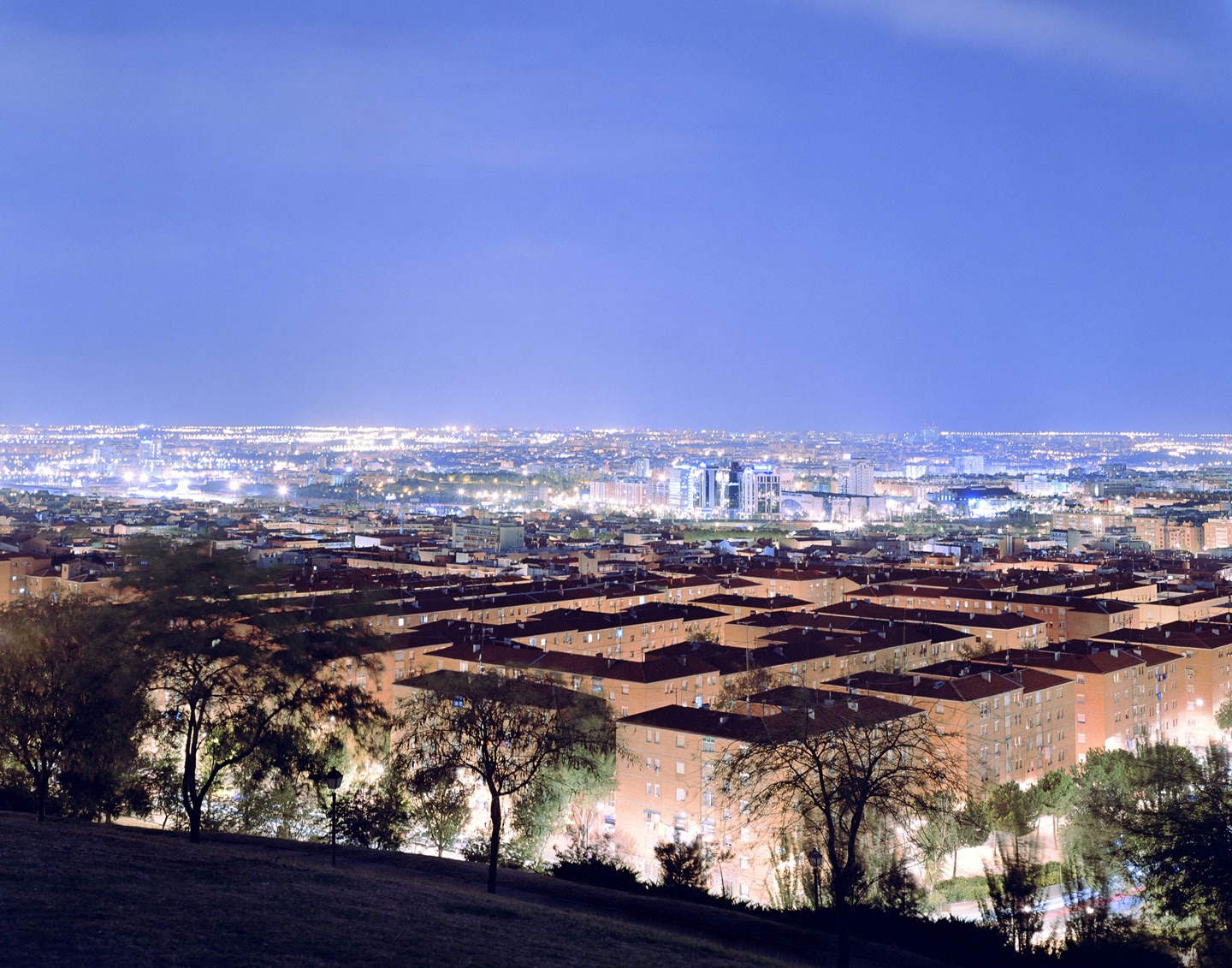

The photographic image has become such a common form of and tool of communication which has increased the collective file of images we all share. Connected to this, as an image maker I have to keep in mind the recognized semiotics that people will find in my work. One of these is the city skyline at night. It has become ubiquitously connected with the identity of place through the travel/tourist postcard (and the social media photograph one could argue as the contemporary equivalent). I have therefore kept the identity of the cities in Lux less obvious by excluding the city name and the most iconic signifiers (usually man-made urban) as a way to keep the viewer in the images looking for the indentifying clues they expect to find. I replace the city name with Metropolis as a way of expressing the interchangability of these place in regards to larger impact. The latitude and longitude coordinates in the titles draw in the language of mapping and location necessary to diferentiate each place and that lead naturally back to the NASA map. This reconnection to the map threads a link between, the here of the viewing context (the viewer) and, the there of the Lux city, in relationship to the entirety of the planet, building a much more layered conversation in the work about place and a larger global system.

Can you describe your approach to making the photographs? For example, why did you often include vegetation in the frame?

My process for shooting in each location started with research about the geography of each city in relationship to the underlying and surrounding landscape. I tried to include the intersection natural elements or the land, and the city to present a conversation between the natural and urban and to suggest what might have been before the city was built. I also tried to find distances or angles that gave the feeling of a “portrait” of each city in the final image.

To start, my research included image searches for viewpoints, looking at maps and investigating locations through Google Earth. Contacts in each place would send a description and/or examples of the general viewpoint(s) before I arrived (and I’d always avoid the recognized or familiar/known spots). I’d stay in each city for usually 2-3 nights and take between 1-3 shots/sheets of film as the exposure times for each shoot took between 1- 4 hours depending on my proximity to the light source. A self made rule was that I would never shoot alone. I photographed using a 4×5 field camera with a kit with 3 lenses and a lightweight sturdy tripod that together could fold up to fit into a backpack that I could easily carry to sometimes-tricky locations. While in a way I ended up with a somewhat methodical process each location had its own challenges. Because of this, each image I took inevitably has its own story behind it.

You took your photos in the US, Western Europe and Japan. Did you find any difference shooting in these three parts of the world?

The main difference I noticed photographing in these three regions was the cultural approach to being outside at night. In the US I found a lot of fear around nighttime and it is generally not acceptable to be outside at night, especially in parks. For the most part in Europe a relationship with the natural world seemed to be a more integrated part of living in a city. Parks in most cities are open late and it is normal for people to engage in a range of recreational or social activities after dark in these natural places. This relaxed attitude made these places feel a lot safer. Out of the three regions, it felt the most acceptable to be outside at night in parks and natural spaces in Japan. On a few occasions the trails we took that lead up a mountain or through the woods to a viewpoint were lined with speakers pumping out Japanese pop music. It was pretty great and surreal to have this soundtrack to our destinations. Often we’d also find vending machines that dispensed warm coffee and tea in cans at the top which were appreciated during long shoots in the cold.

The main visual difference between the regions you’ll see is is the color of the light. This is due to the use of sodium vapor versus mercury light bulbs used in streetlights. Sodium vapor bulbs are a warmer temperature and are used in most of Western Europe. The US uses a combination of the two and Japan uses mostly mercury bulbs. The images from WE are therefore much warmer, from Japan much cooler, and from the US somewhere in between.

In terms of cultural differences in response to the project, I found that Western Europeans were already engaged in conversations about the environment and bigger global issues. Most cities in the region had a public dialogue going on about climate change and environmental responsibility even as early as 2005 when none of this was really being addressed in the US. In both Japan and Western Europe it was clear that the idea of being an artist is taken very seriously and I felt deep respect for the work and a consideration for the rigor it took to undertake the project (especially at that time when global travel and communication was far less prevalent). So many people generously went out of their way to support and assist me in making the work in all three regions but I would say this level of seriousness and respect was not always prevalent in the US. It amplified that we have a very different cultural attitude about the arts here.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Lux?

Lux was the first major project I undertook out of graduate school and I suspect the history of landscape painting and Western landscape photography, both of which I studied, had a combined influence on my approach to the compositional language of the project. In hindsight, I think that Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Seascapes also had an influence on the work. It is a series that has stayed with me since I was first introduced to it years ago.

I am also a fan of the atmospheric qualities of William Turner’s paintings. The Great Western Railway (1844), is a favorite of mine. It depicts a steam train pushing through a veil of smog. It showcases the slamming together of the man-made and natural at the height of the industrial revolution, and recognizes the train as a pivotal invention that was to have a great effect on our understanding of, and our relationship to, time and place. I’d argue his sublime atmospheric aesthetics express the deep spiritual tension or rift the influence of this (and many other man-made) invention(s) of the time, would have on the perceived position of humans in relationship to the natural world.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Aside from Western landscape photography, the work coming out of the Düsseldorf School of Photography (Thomas Struth, Adreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, etc,…) had some influence on the kind of photographs I was thinking about and making out of graduate school. Studying with Penelope Umbrico during that time also influenced my thinking in terms of how the photograph functions in visual culture and subsequently my approach to image making and to teaching photography.

Building on this, more recently I have had two deeply formative experiences that have influenced my work in very different ways. One was the experience of living embedded in the Arctic landscape through multiple trips north, starting with a move to Alaska for 6 months in 2010. The other was traveling as a guest lecturer/tutor with Unknown Fields Division (UFD), an innovative architecture unit that takes groups of architecture students and professionals from the fields of art, science and technology on expeditions to some of the most extreme places on the planet to bear witness to a range of ecological, political, intellectual, and sociological global networks.

Through these two experiences I came to understand both the impact bearing direct witness has on the depth of meaning possible through my images and therefore their power and success; as well as the role the photograph and visual media can play in describing incredibly complex ideas.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Out of a much longer list: I love the range of ways Joan Foncuberta questions the veracity of the photograph and plays out the blurry line between fact and fiction; I am drawn to the relationship between concept, material and installation in Lisa Oppenheim’s work and the sophistication in how she connects landscape and politics; and I am particularly interested in the playout between 2 and 3 dimensions in Erin Sheriff’s recent work.

Deana Lawson, Jim Goldberg, and Pieter Hugo are all incredibly powerful portraitists. I have deep respect for the way they each build out important critical social content in their respective work over time. I admire Tacita Dean’s mixed media and experiential approach to using photography and the photographic in her work. I’m including Eija-Liisa Ahtila here as well, who is a Finnish artist who uses the moving still (in a photographic way) to create captivating multi-channel installations.

Finally, I am a big fan of how Letha Wilson interweaves photographs with sculptural and architectural materials; and I am deeply captivated by Michael Lundgren‘s work and particulary in the way his photographs work as sets or in sequence (the book format).

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Fragment. Whole. Systemic.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025