Discordia – Magnum Photojournalist Moises Saman Presents His First, Terrific Photobook

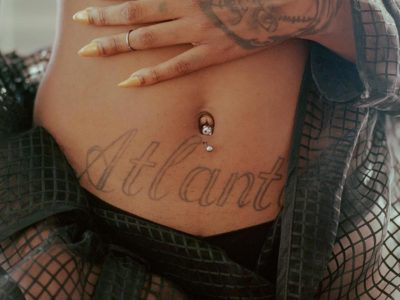

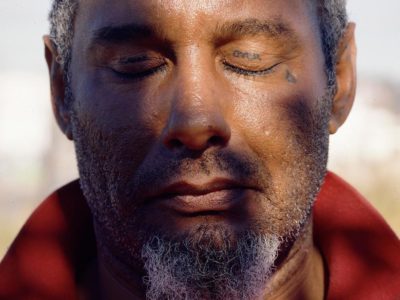

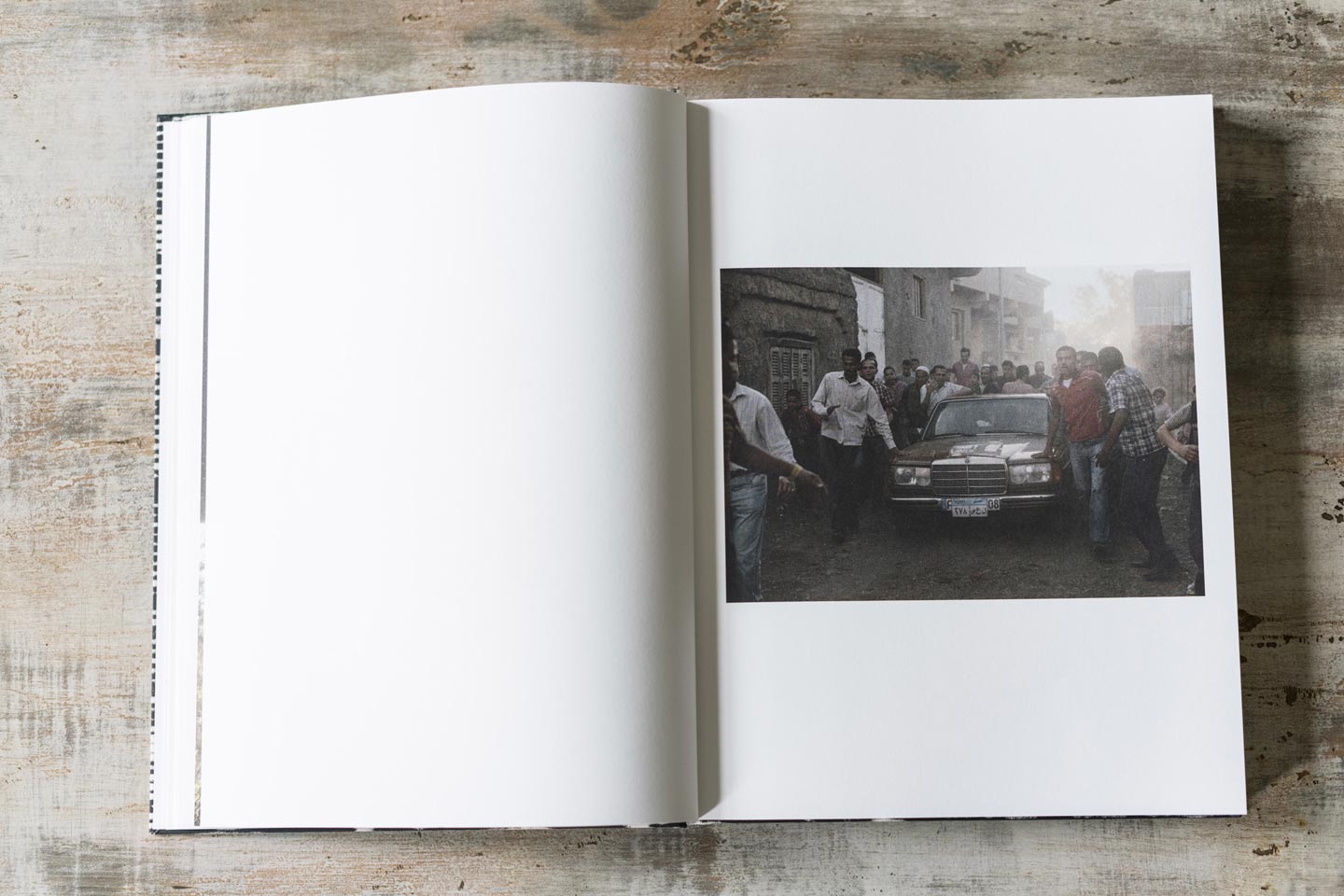

Spanish American photographer Moises Saman – a member of Magnum Photos and one of the top photojournalists out there – discusses Discordia, his first self-published photobook made in collaboration with artist Daria Birang. This terrific book offers a subjective narrative of the events Moises covered in recent years in the Middle East – buy your copy from the book’s website.

Hello Moises, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I am interested in everything that has to do with the human experience. In my role as a photojournalist I am drawn to the social issues that are shaping my generation.

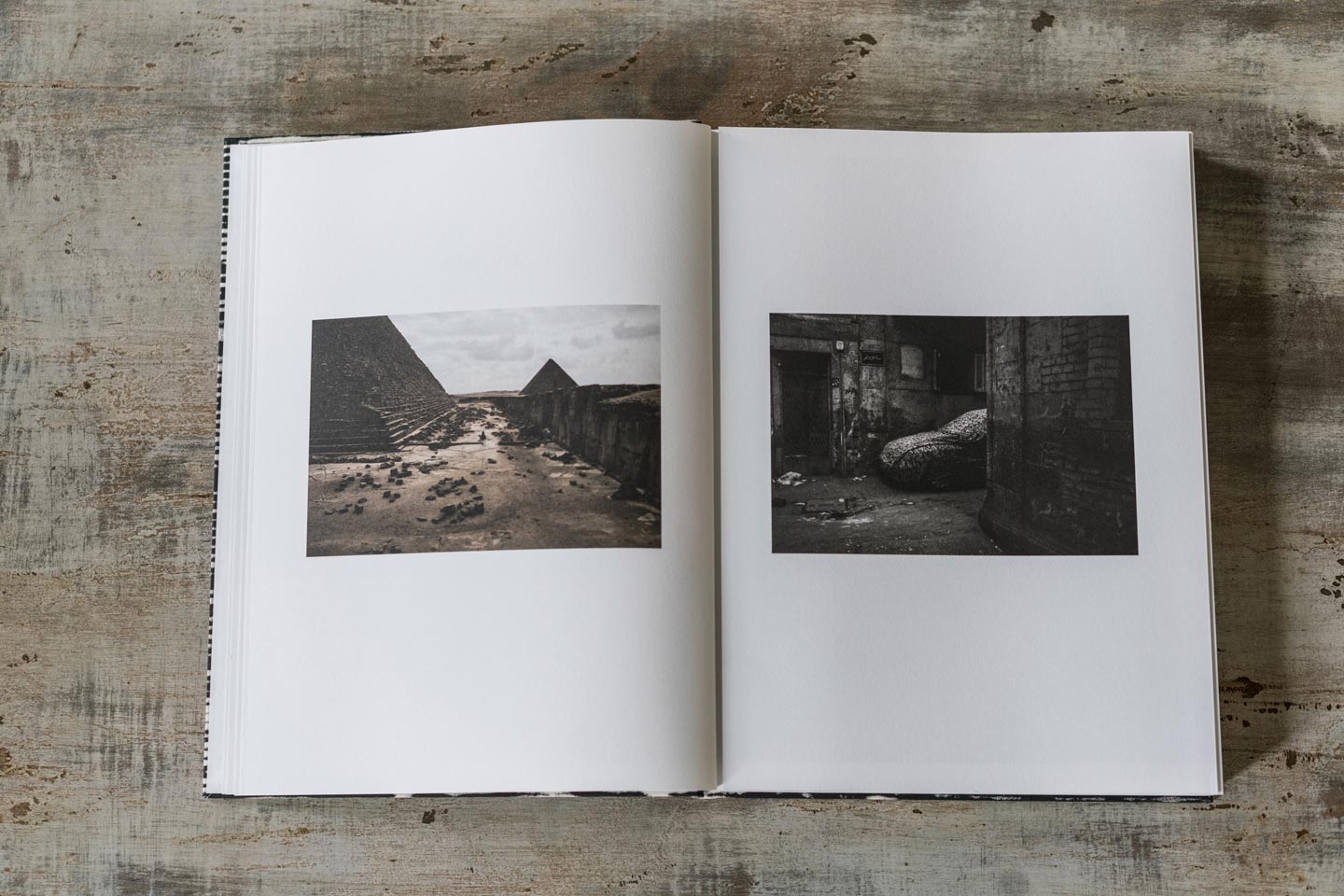

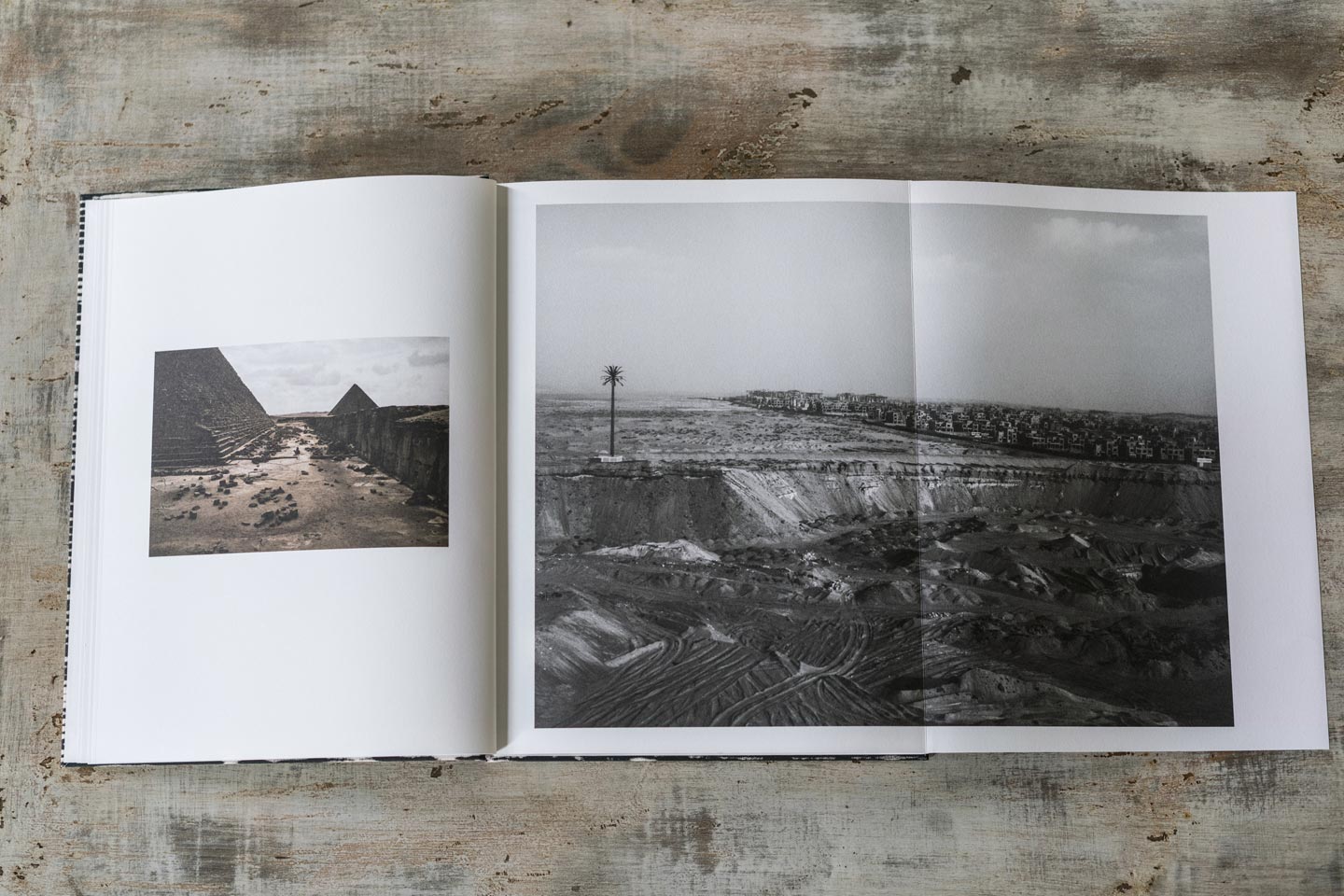

Your new photobook Discordia brings together images you took in the Middle East between 2011 and 2014, as war and revolutions broke out in countries like Syria, Egypt, Lybia and Turkey. The pictures however are presented in one single sequence, with no captions, as if they were part of the same narrative. Why did you choose this approach?

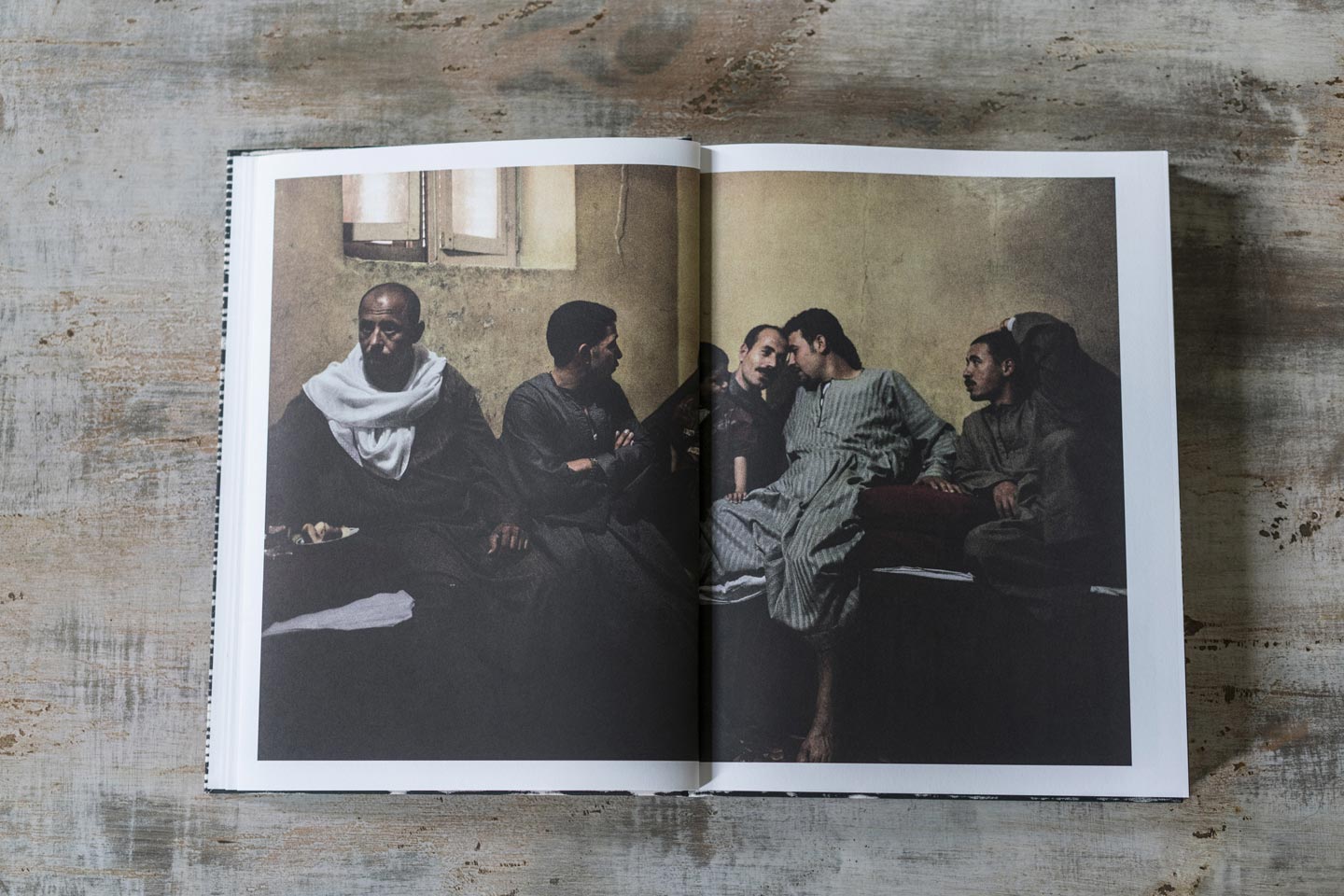

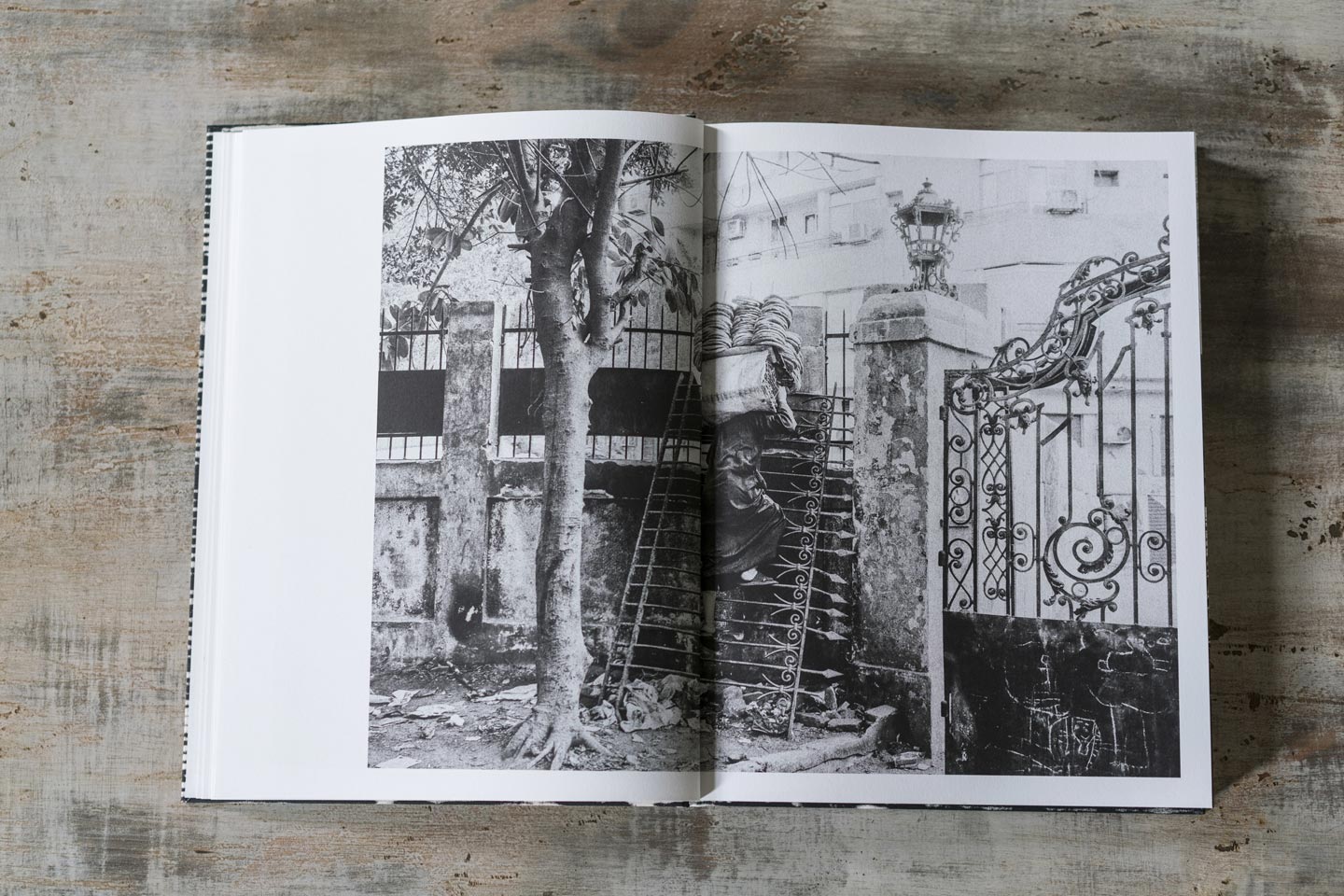

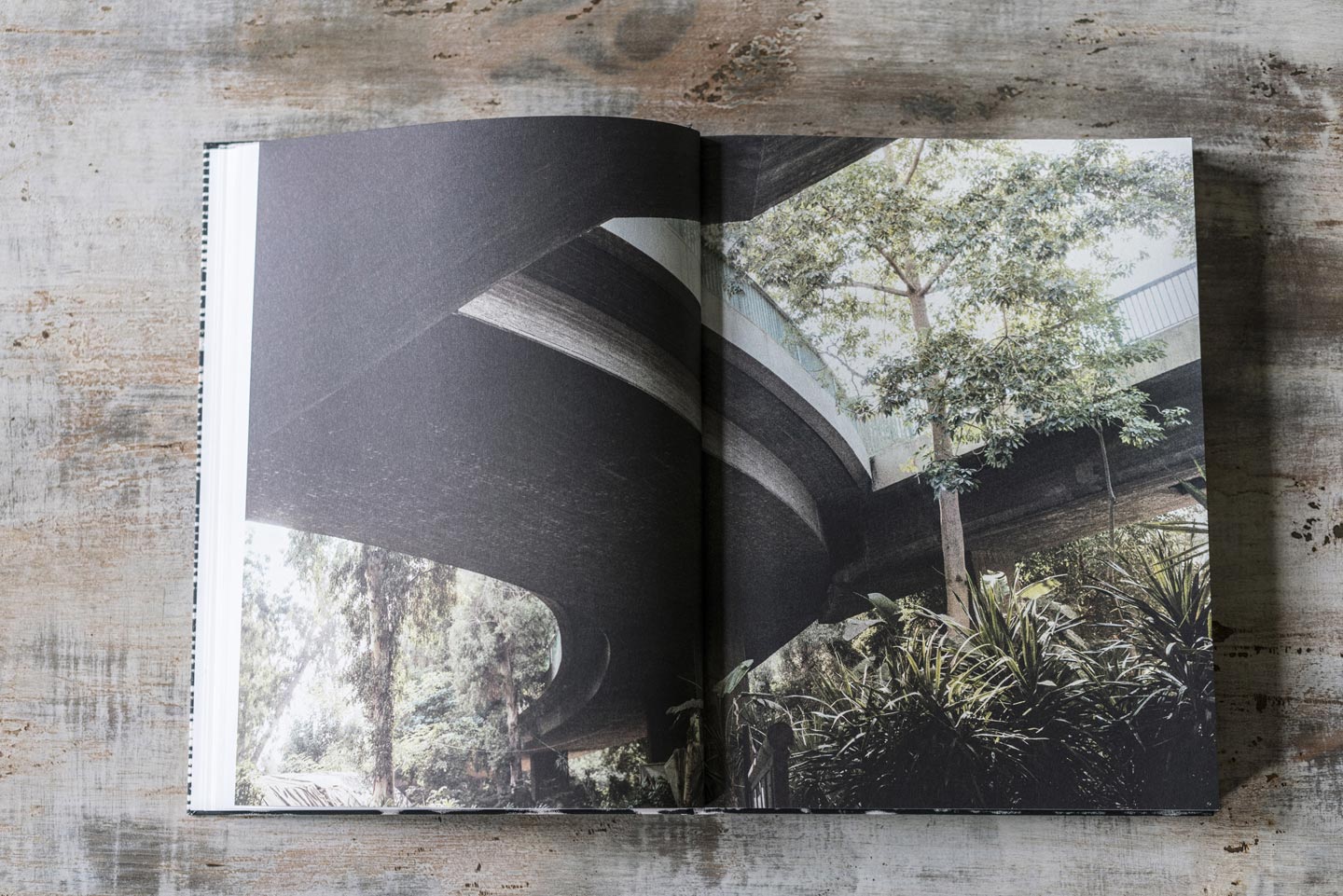

The idea for the book came from my desire to make sense of the confusion and uncertainty that ultimately defined my time living and working in the region. In the course of these past few years many revolutions overlapped, and in my mind became one blur, one story in itself. In order to find some introspection I chose to loosen my approach as a photojournalist by shifting the focus from the “news” aspect of the story to a more ambiguous visual narrative, one that was more in tune with my own experience witnessing the blurring of the lines between victim and perpetrator.

Discordia is not a first draft of history, nor do the photographs intend to lecture the viewer about the complexities of the Middle East. It is simply an up-close and honest visual record of the time I spent living and working as a photojournalist in the Middle East.

Your pictures regularly appear on top publications like TIME, The New York Times and The New Yorker. What does it mean for you to have published your own book?

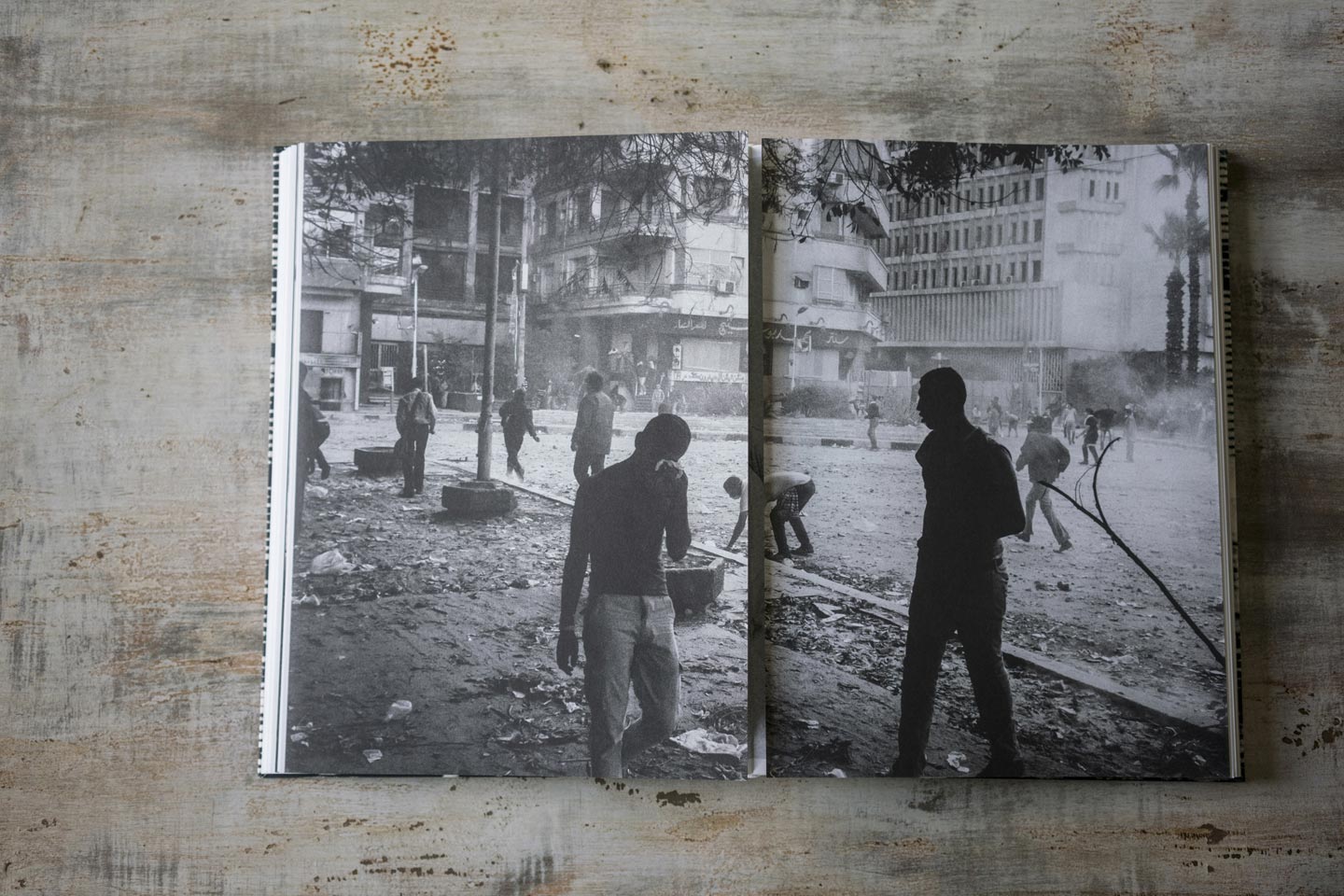

This book represents a personal and honest attempt at making sense of what this period in history meant to me, beyond the work that I was producing on assignment. The hectic pace, and the reactive nature of covering the news on assignment did not allow for much introspection. However, with time it became evident to me that at a visual level, the facts alone did not grasp the complexity and implications of this historic transformation. During my five-year engagement with the region it became impossible not to question the simple narratives of good vs evil, after seeing first hand how easily the roles of victim and perpetrator can change. It was precisely in this shifting landscape where I found my focus, and where I was able to project my own questions and insecurities.

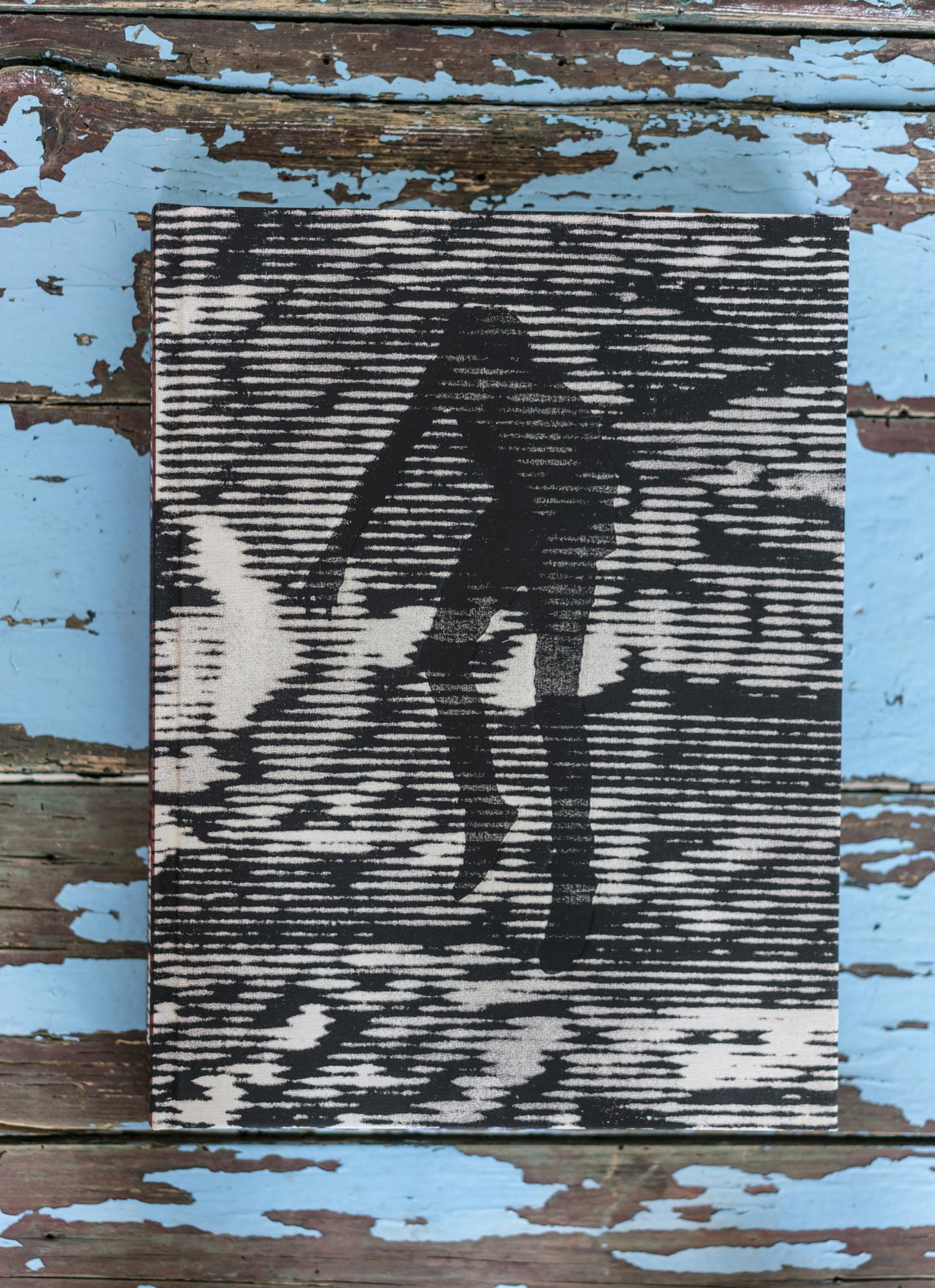

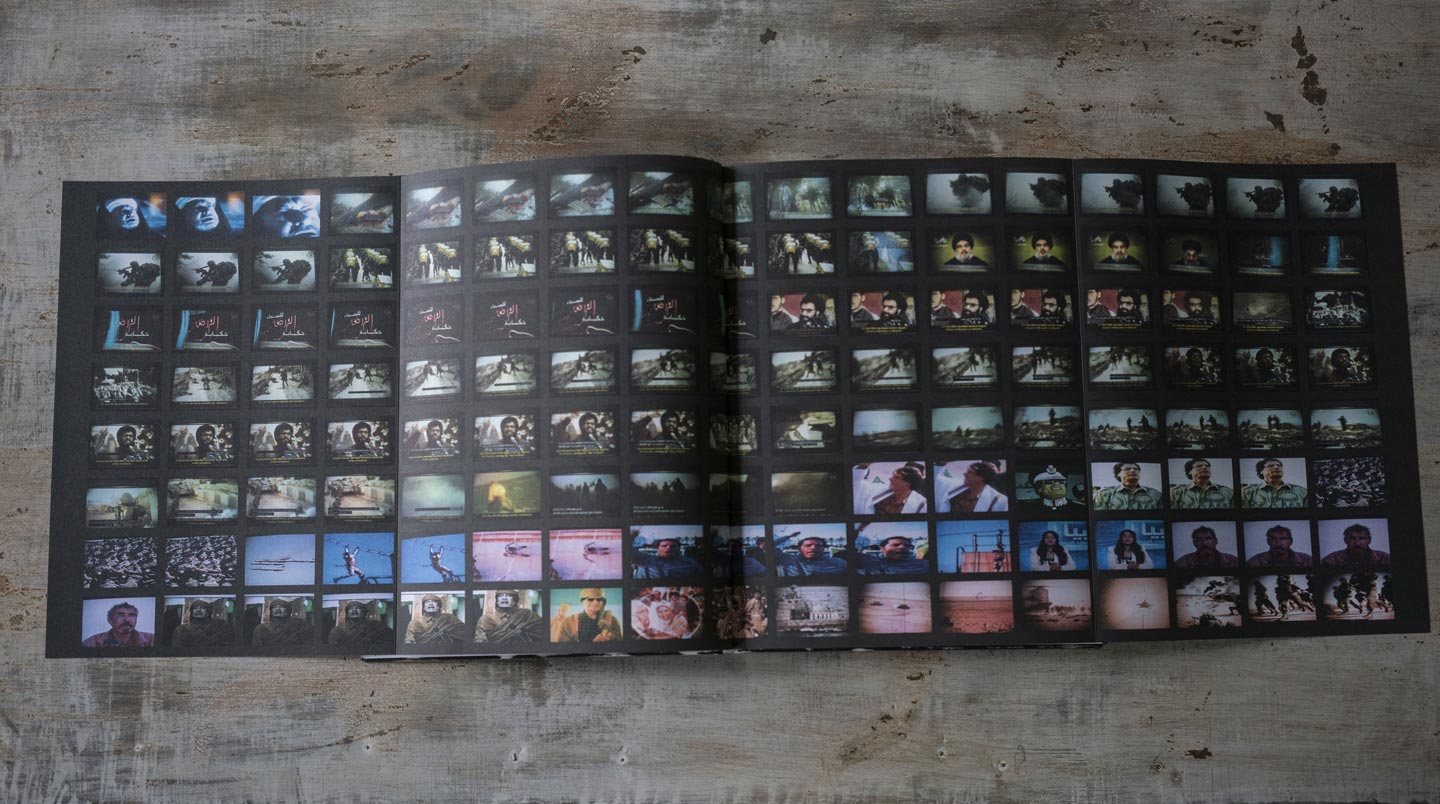

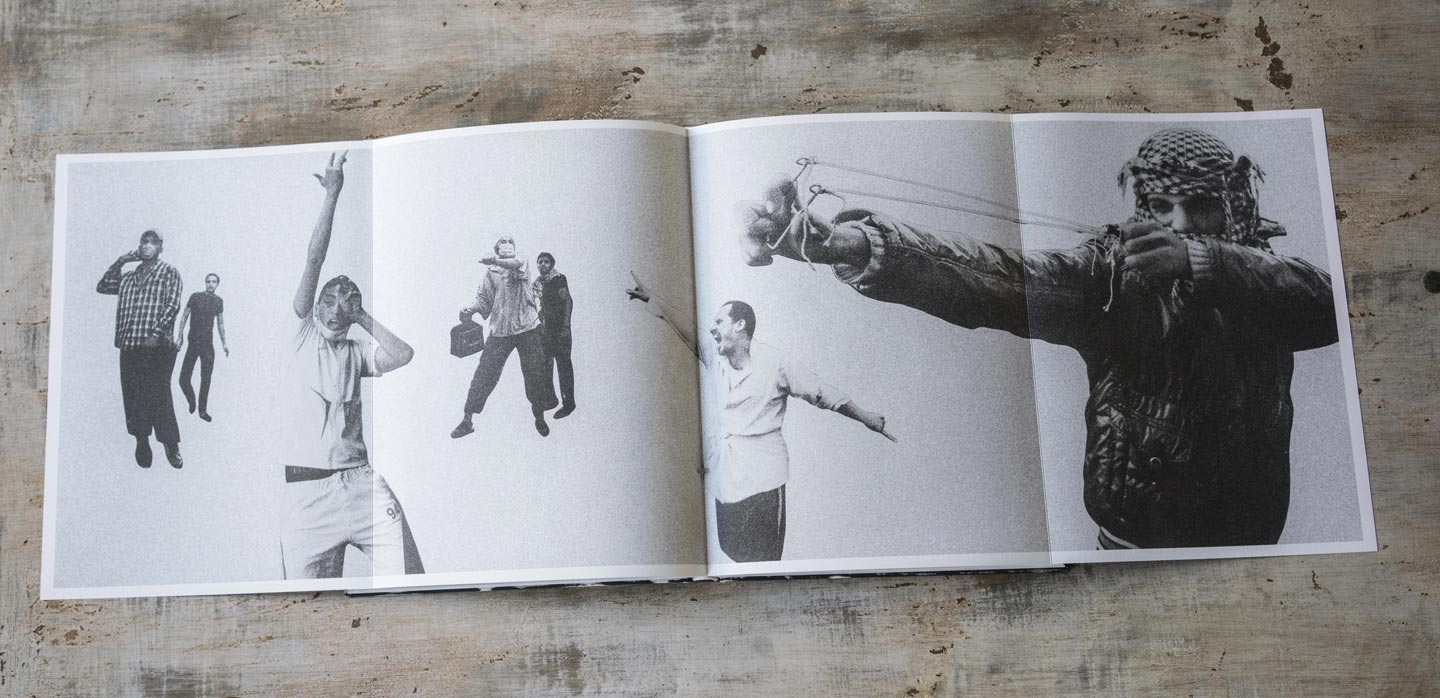

The book includes several collages that Dutch-Iranian artist Daria Birang made from photographs taken by you. How was this collaboration born, and what is the function of the collages in Discordia?

I have collaborated with Daria in the past, and her artistic background was incredibly helpful in constructing a non-linear narrative to the story. The idea for the collages came from Daria, and they emerged from our dissatisfaction in portraying the protesters simply as the subjects of an action image; instead we became obsessed with their body language, the theatrics, and performance-like rituals that I saw repeatedly during the countless demonstrations and clashes I photographed.

Daria Birang also worked with you on the editing and design of the book. What guidelines did you follow when choosing and sequencing the pictures?

Over a period of at least a year, we went through thousands upon thousands of images stored in my hardrives. Initially we were drawn to the more ambiguous images, devoid of apparent news value, but with certain elements of tension, drama, humor, absurdity, that allow the viewer a greater engagement by sparking their curiosity. The sequence of images were meticulously organized, like in a puzzle, where each single part is bound to the next to create a larger end. To tell the story the way I lived it, I felt the need to go beyond a particular event or location and play with picture pairings that reflected a shared experience, or the lack thereof.

What was the most difficult part of making the book, and how long did the production take?

The most difficult but at the same time interesting part was creating the rythm of the story through the sequencing of the photographs. Once we had a somewhat final sequence, it took another year of finetuning and designing before we finally went to print.

Why did you choose Discordia as the book’s title?

Discordia is the Greek goddess of chaos and strife, a major character in Greek mythology. I found many parallels between the Greek tragedy and the story of the Arab Spring.

Is there any piece of advice you would give a photographer looking to self-publish his photobook?

Make sure you understand what is the story that you want to tell, and tell it with your own voice.

What feelings do you get today looking at the images of Discordia?

I am grateful for all the people that helped me throughout the entire process, I could not have done this book alone.

Keep looking...

How and Why Palestinian Women Sneak Their Husbands’ Sperm Out of Prison

Subjective Trophies — Pierre Abensur Portrays Hunters Showing Off The Animals They Killed

Ten Best #FotoMobile Submissions Vol. 66

Hahn & Hartung Explore How Indonesia Puts Up with Volcanoes, Earthquakes and Tsunamis

FotoFirst — Los Angeles Becomes a Giant Movie Set in Gaudrillot-Roy’s Cinematic Work

FotoFirst — Photography Duo ‘Mount Fog’ Look at the Flooded Banks of Italy’s Longest River

After Alice, Siân Davey Photographs Her Other Daughter Martha and Her Group of Friends