The Black Mountain — Antoine Bruy Explores an Impoverished Region in the North of France

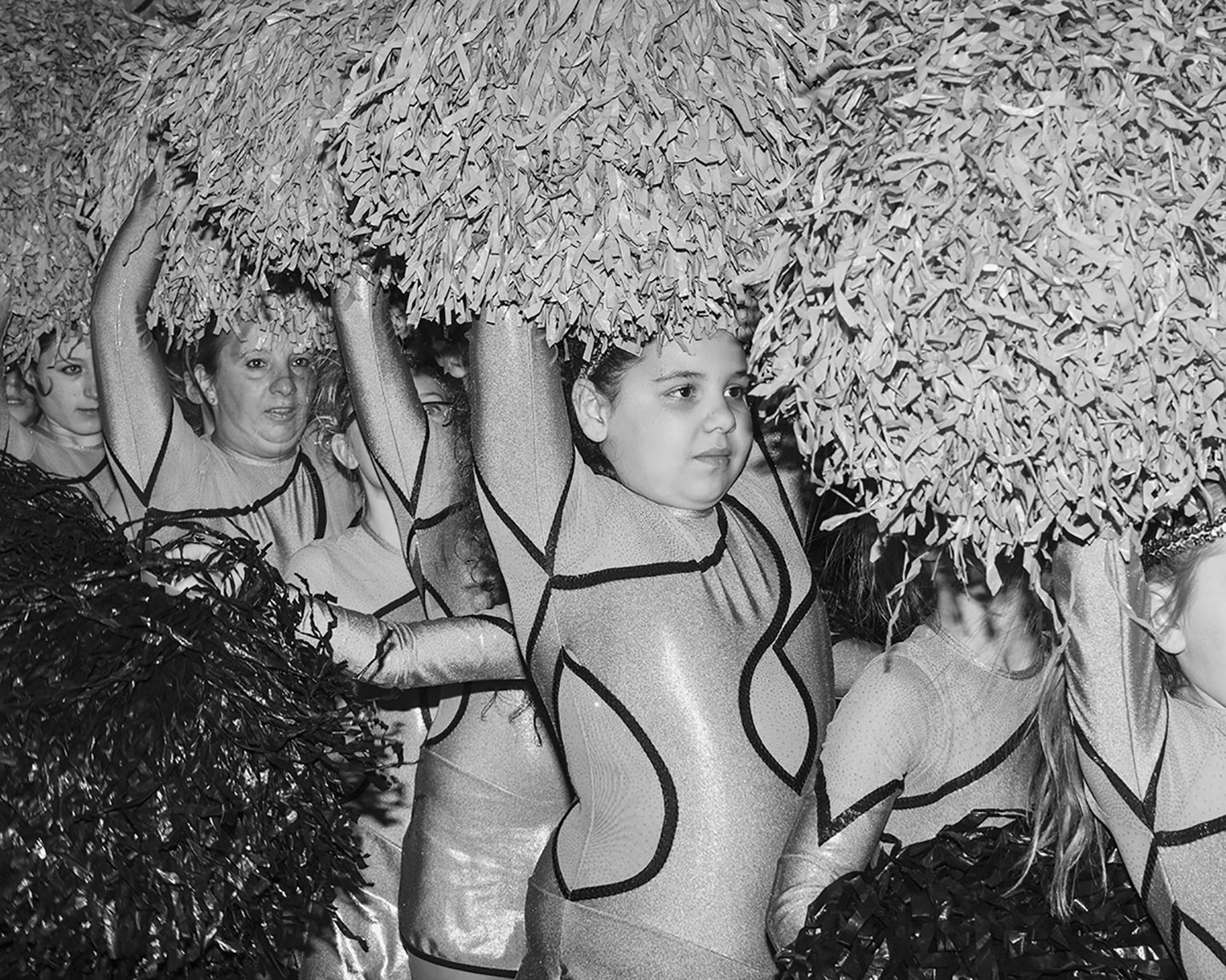

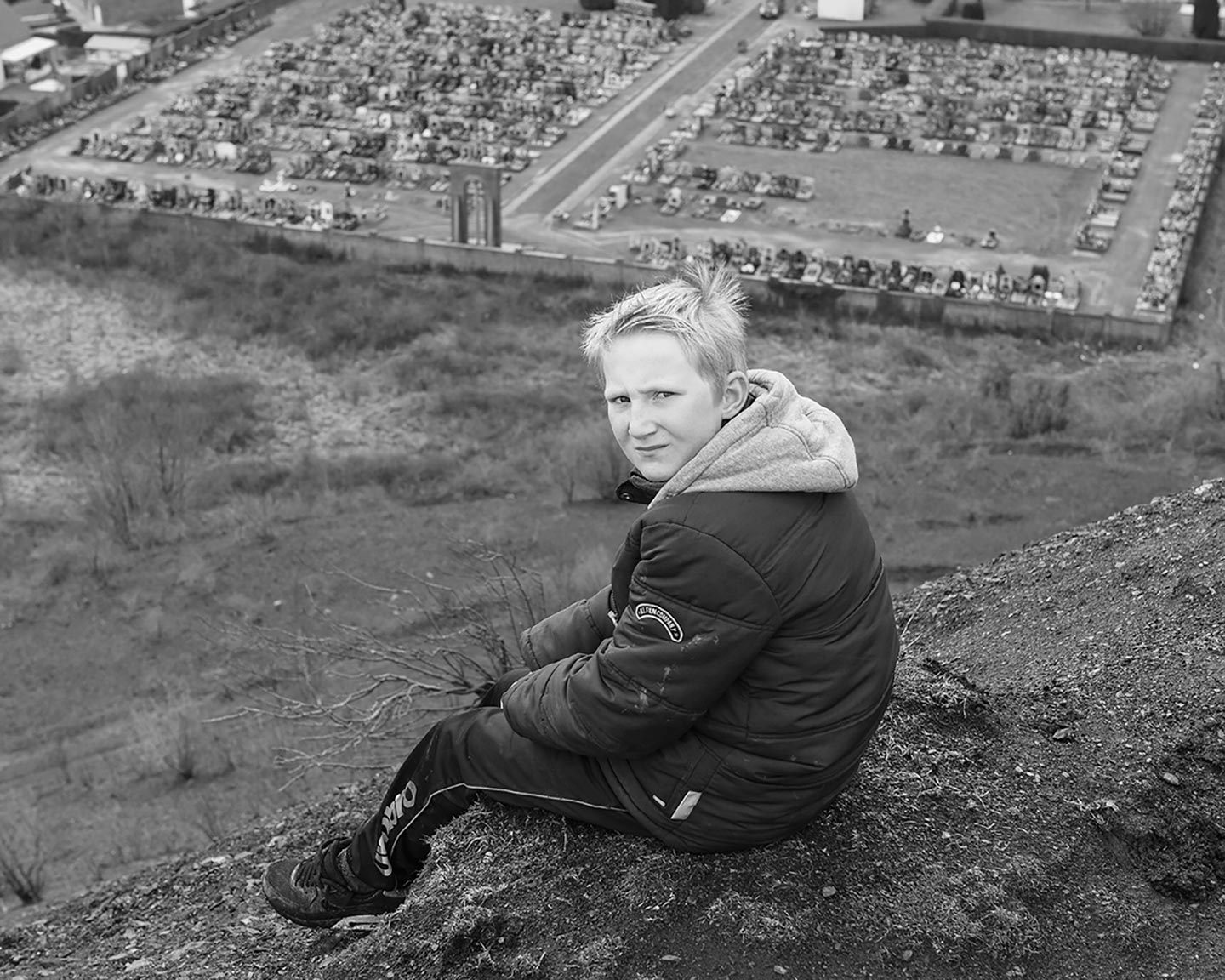

You probably remember 30 year-old French photographer Antoine Bruy from Scrublands, his beautiful and popular series about people who chose to live off the grid on the mountains of several European countries. Antoine has recently been putting out new, great work, including an ongoing series called La Montagne Noire [tr. The Black Mountain], a subjective reportage shot in black and white that focuses on a group of small towns in the North of France. These towns are all located in a once prosperous region thanks to the flourishing mining industry; but since the last mine closed in the early 1990s, things there have changed for the worse.

Hello Antoine, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

My photographic work is based on the relationship between men and their environments. The structures humans build and the reasons they build them for, as well as the economic and intellectual circumstances that determine their construction, contribute—to different degrees—to my practice as a photographer. Through the study of the economic and philosophic conditions that allow for specific lifestyles, I’m interested in exploring the organization of the spaces and territories we inhabit on one hand, and how we experience these spaces in a more intimate and existential dimension on the other. Starting from a reflection on the nature of isolation both as a deliberately chosen and an “imposed” lifestyle, I question our societies as forms of living together.

However subtly, my work is constantly blurring the line between reality and fiction, and I’m not setting out to offer any answers but to make visible unexpected cracks in our highly hierarchized societies. In other words, rather than wondering what our societies could be like, I prefer to question their current form.

Please introduce us to La Montagne Noire.

La Montagne Noire is a body of work I started in 2014 about the territory of «Bassin Minier» (coalfield or coal furrow) that extends across the north of France and south of Belgium; it takes a look at how this region evolved since the last mining company shut down in 1990. The slag heaps that can be found all over the place are literally like artificial black mountains, and became the symbol of this project.

Why did you decide to make work in the Bassin Minier region, and for how long have you worked there?

I grew up in an area known as the«Nord pas de Calais», which is close to the Bassin Minier, and since a very young age I’ve been fascinated by how the mining industry shaped the landscape. Later I realized that even though I was living close to the Bassin Minier—which in the meanwhile has been included in the UNESCO World Heritage list—I didn’t know much about these small towns and how greatly they were impacted by the collapse of the mining industry. I was curious to see how daily life could look like over there, and what the situation was 25 years after the closing of the the last mine.

Based on your experience, how would you describe the Bassin Minier territory and its inhabitants?

The Bassin Minier has a pretty bad reputation—poverty, unemployment and alcoholism are very common in the area, and are the highlights of most representations of the region (often in a derogatory way). Personally, I had mixed feelings about the Bassin Minier: the small, quiet towns I came across were pouring boredom, sadness and helplessness out of every wall of every house I could see.

A two-centuries history of mining has produced a specific and complex culture that strongly marked both this territory and its inhabitants, and continues to do so now that all the mines are closed. The high levels of social control, as supported by the mining companies, have led to isolation, lack of initiative, and lack of mobility; but also generated strong social bonds and commitment to hard work. I met people whose present is filled with memories of an idealized past when, even though they worked hard, they had jobs and their towns were more lively; but the future holds no promises for them. It sounds dramatic but this is what I feel every time I’m wandering in the small tows of the Bassin Minier.

Can you talk a bit about your approach to the work? What did you want your images to communicate?

My goal was to capture the state of desolation that characterizes most of these towns, and to show how their inhabitants have been abandoned by the the State, somehow. Every time I go to the places I’ve visited—like Bruay La Buissière or Anzin in France, or to Colfontaine in Belgium, just to mention a few—it’s quite weird for me how I feel so far away from home, when I’m actually just an hour away from Lille where I live. It’s like ending up in a dead end reality: you can feel that most of the people who live there are stuck and have no real perspectives for the future. Nonetheless, it’s not rare to meet characters with open hearts and joie de vivre, which is amazing for me: as an outsider, I can only see desperation.

You usually shoot in color. Why did you work with black and white in this case?

First of all, because I simply like it: the black and white shows textures far better than color does, and it was a great way for me to give a mineral aspect to the images. I’ve been wanting to work with black and white again for quite a while, to do something different from what I was used to. The works She Dances on Jackson by Vanessa Winship and Imperial Court by Dana Lixenberg played a role in this decision as well: they were like a revelation for me. Using black and white photography was also a good fit for my intention to present the Bassin Minier as a place which is like frozen in the past. I wanted to make images that had the potential of being timeless and that could communicate the strong feelings of melancholia and sadness I often felt while wandering in the area, and the black and white helps a lot with emphasizing these emotions.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on La Montagne Noire?

She Dances on Jackson by Vanessa Winship, Imperial Court by Dana Lixenberg, In Flagrante by Chris Killip, Songbook by Alec Soth, Bad Weather by Martin Parr. Also, films by directors like Ken Loach, Les Frères d’Ardennes and Bruno Dumont.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Travels, films, literature, social sciences, photography.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Nadav Kander, Roger Ballen, Pieter Hugo, Rob Hornstra, Daniel Shea, Dana Lixenberg, Richard Renaldi, Joakim Eskildsen, Eric Baudelaire, Taryn Simon, Pieter Ten Hoopen, Paul Graham, Mitch Epstein, Geert Goiris, Bryan Schutmaat, Regine Petersen, Martin Kollar, Andrew Miksys, Paul D’Amato, Clare Richardson, Vanessa Winship, Rosalind Fox Solomon, Trent Parke, Doug DuBois, Stephen Shore, Alec Soth, Marc Asnin, Raymond Meeks, Jim Goldberg, Fazal Sheikh, Richard Misrach, Karolin Klüppel, Patrick Faigenbaum, David Favrod, Richard Rothman, Luc Delahaye, Marton Perlaki, Jacob Aue Sobol, Anders Petersen, Andrew Phelps, JH Engstrom, Nicolai Howalt, Rafal Milach, Alessandro Imbriaco, Richard Mosse, Shane Lavalette, Tamas Dezso, Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs, Mikhael Subotzky, Max Pinckers, David Chancelor, Will Steacy, Dirk Braeckman, Carolyn Drake, Latoya Ruby Frazier, Walker Pickering, McNair Evans, Rose Marie Cromwell, Gregory Halpern, Bloomberg & Chanarin, Tim Richmond, Brandon Thibodeaux, Heikki Kaski. The list goes on.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Intuition. Empathy. Unknown.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024