‘Dream the End’ by Dorje De Burgh Is a “semi-imagined mapping” of His Relationship with His Mother

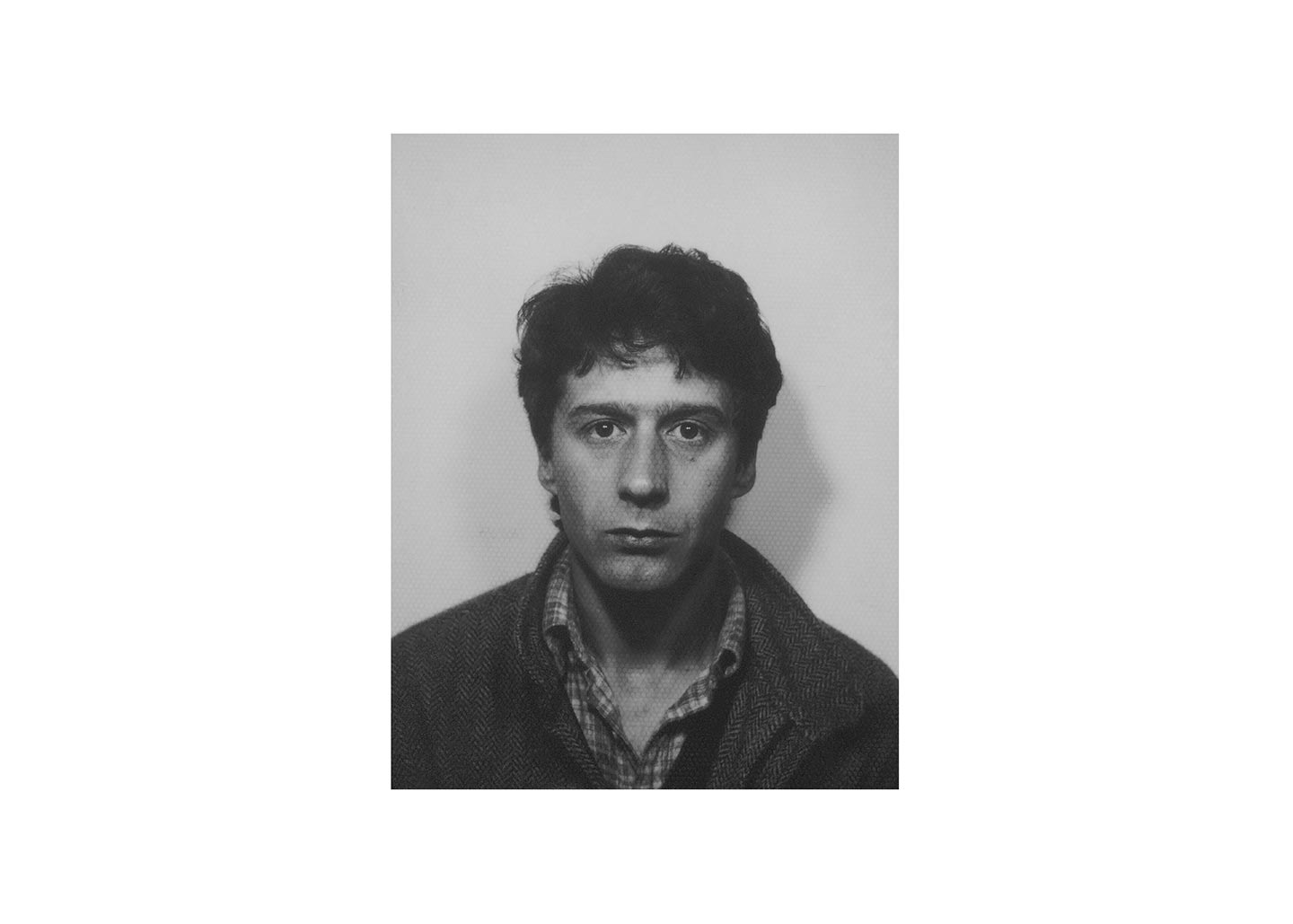

Dorje de Burgh is one of the 12 photographers shortlisted by photobook publisher Void to run for the opportunity of having their work made into a publication, which they offered as jurors of a recent #FotoRoomOPEN edition.

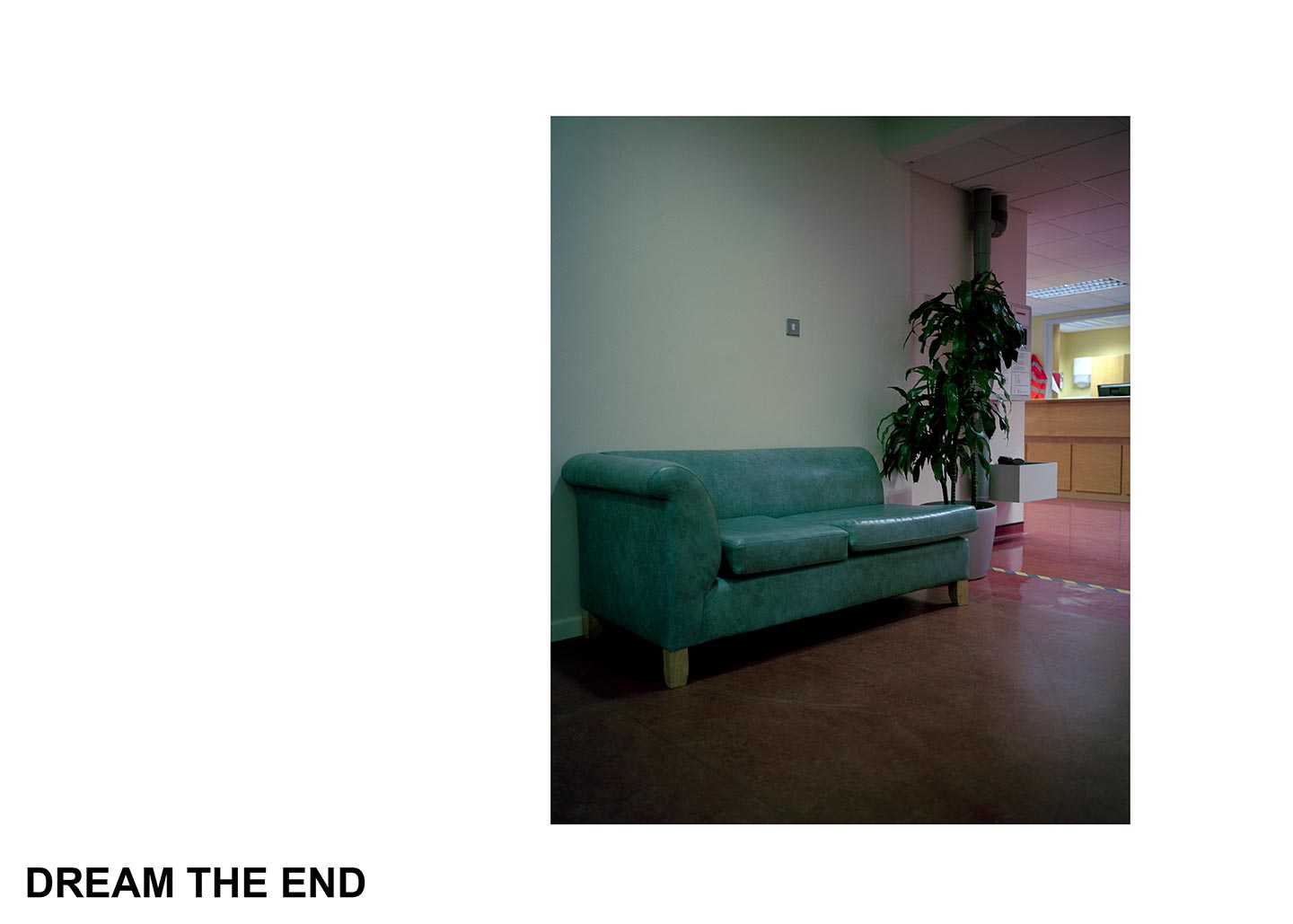

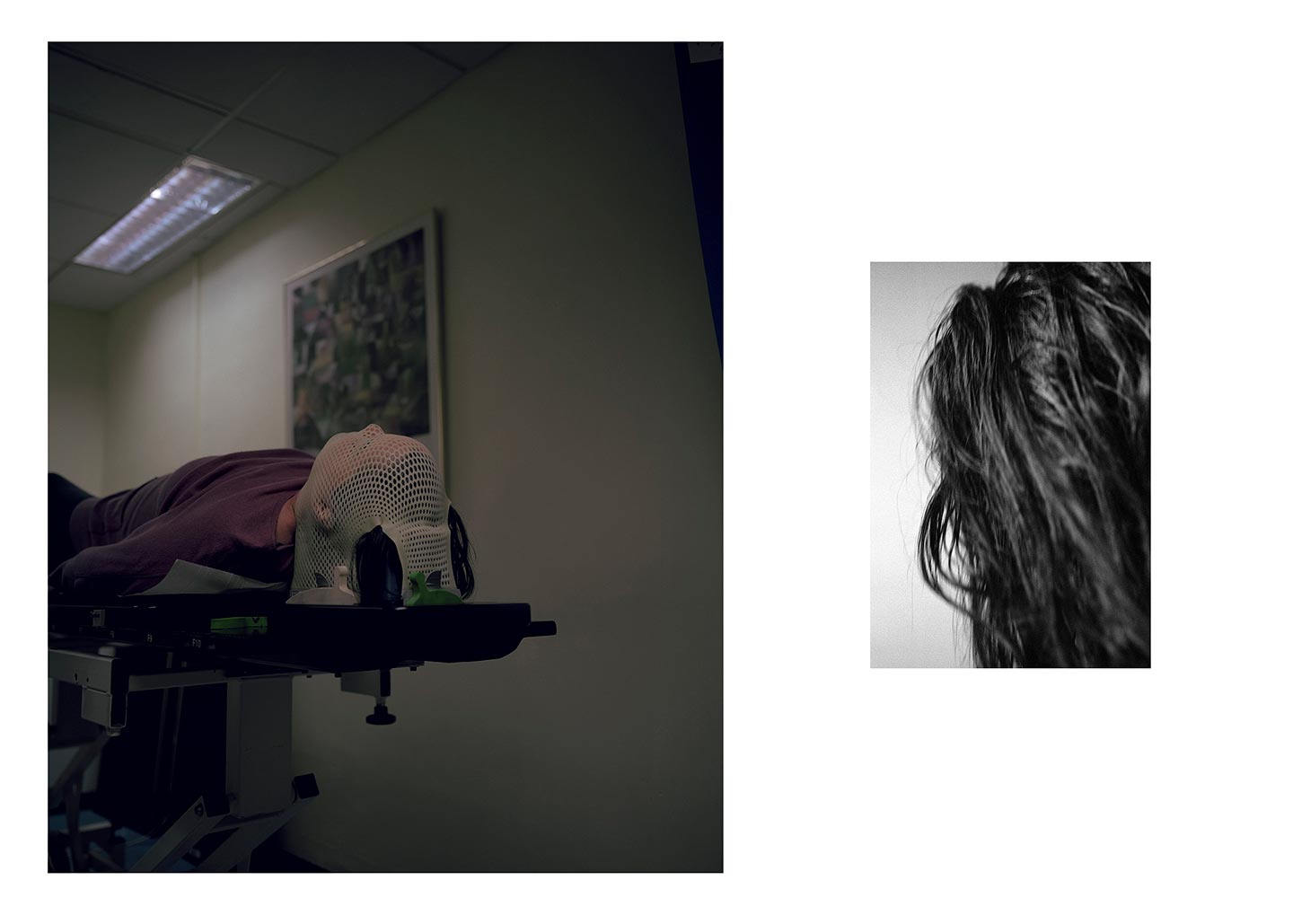

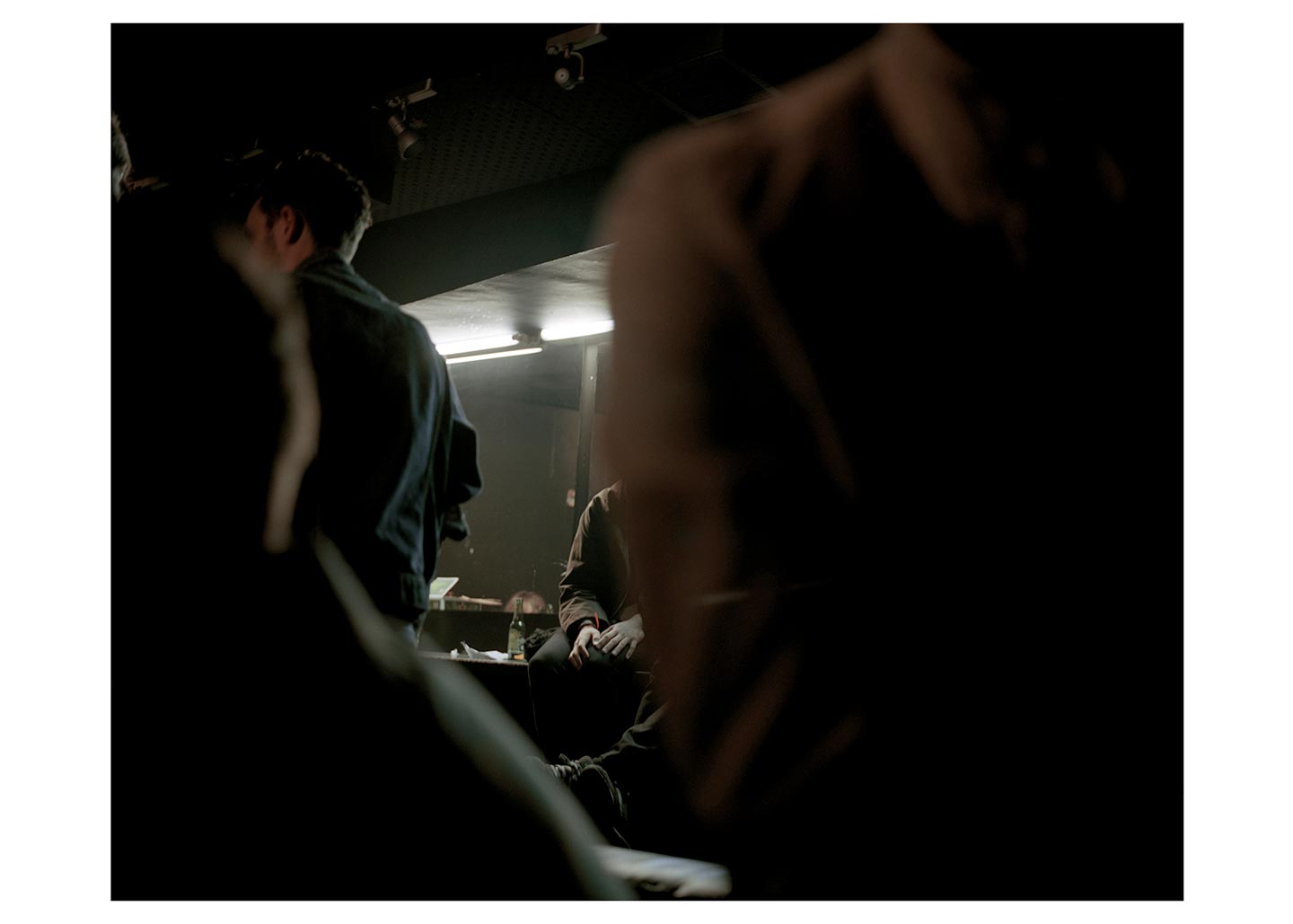

Dream the End by 35 year-old Irish photographer Dorje de Burgh is a series of images deeply connected with Dorje’s personal and family history: “For most of my life, my family mainly consisted of my mom and me. I was lucky: Sherie was an incredible human being, and we were incredibly close, like best friends. But this made her sickness and death an unbearably intense and lonely experience for me.”

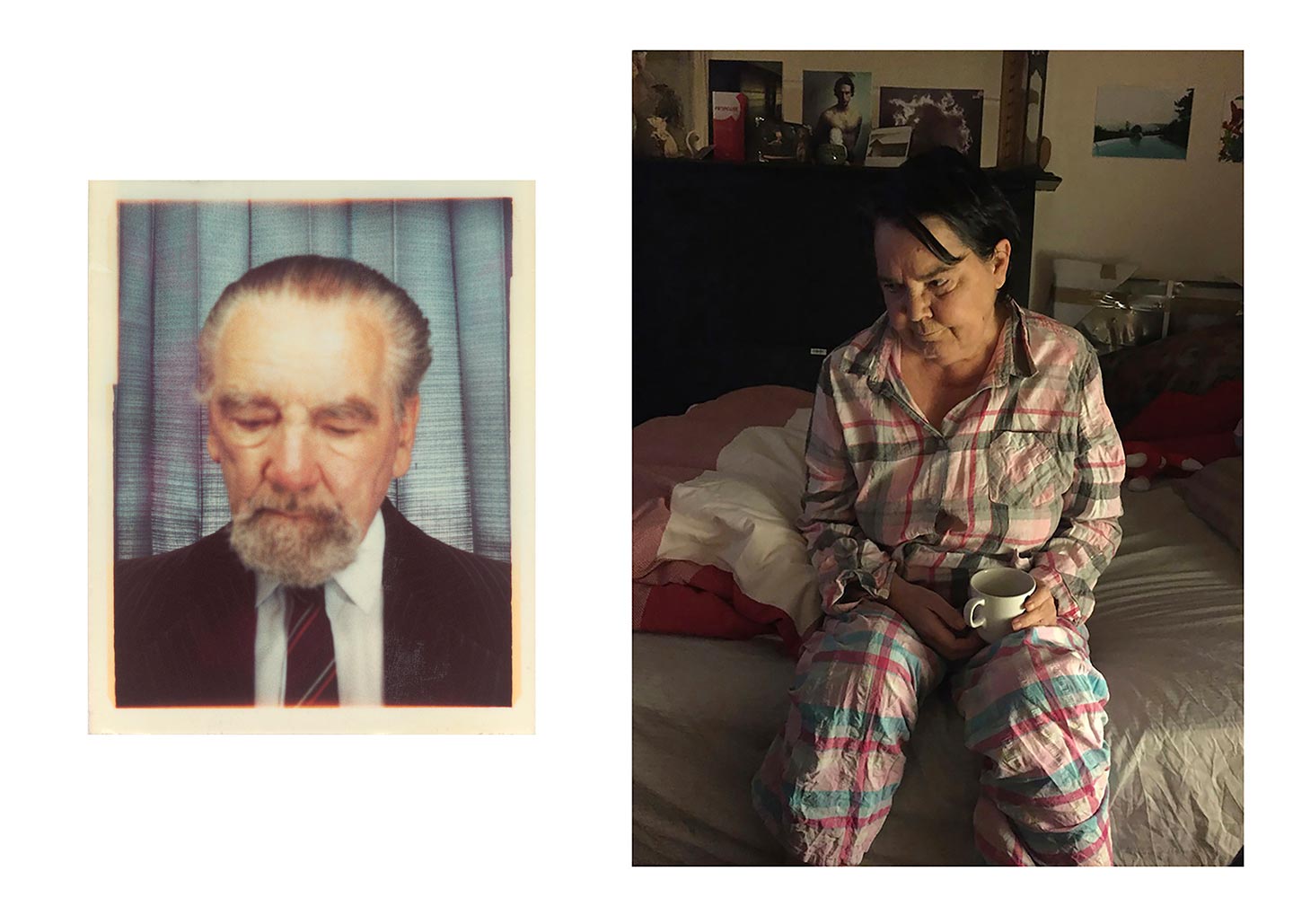

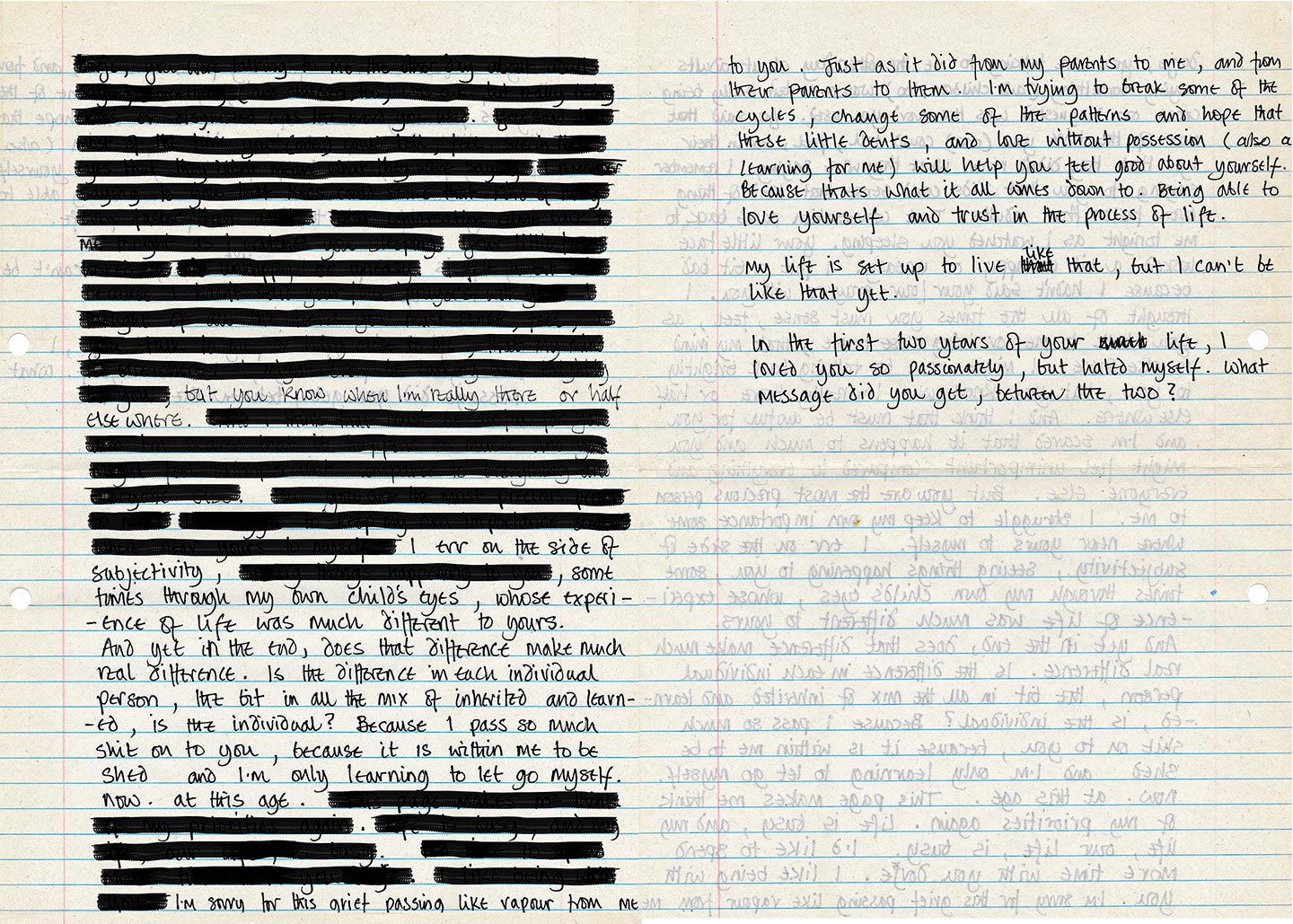

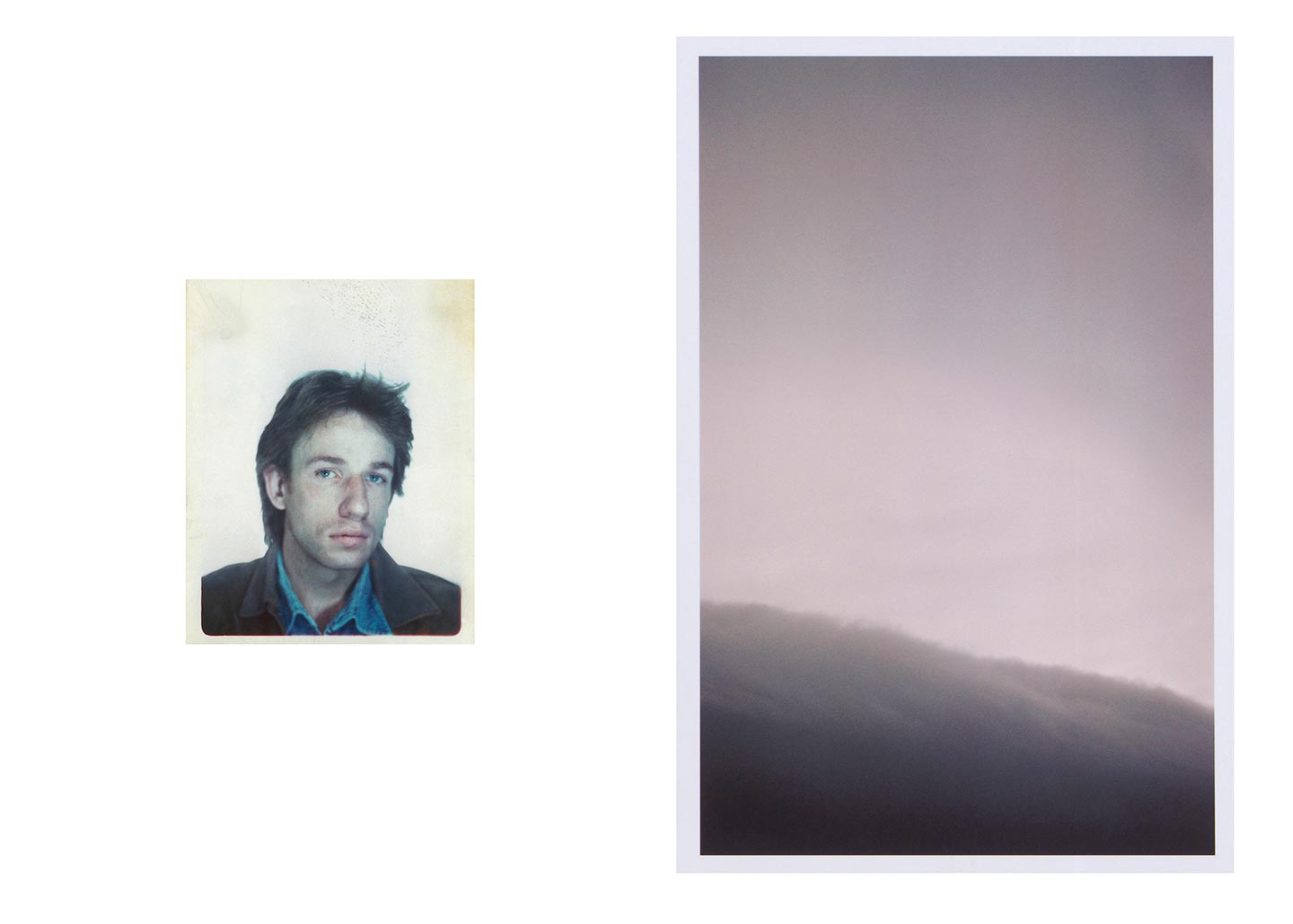

“All families are complicated. Most are full of secrets, and mine is definitely no different” Dorje says as he begins to share the story of his family. “I’ve never known my father; I was close to his brothers when I was a kid, but me and mom broke contact with that side of the family after two of my uncles took their own lives shortly after one another when I was around thirteen. That might sound harsh but it was mom’s way of trying to protect me: she had spent her life navigating her way through and past her own awful childhood, and to be dragged into another dangerously dysfunctional family was simply not an option. This instinct to protect—to break the chain of misery and abuse—implicated that I got to know very little about either side’s actual history, or the root causes of all that pain. My maternal grandfather was by all accounts an evil person and wrought untold destruction on my mom and her brothers, but they survived him and have all become quite beautiful humans who made beautiful lives for themselves and their children, each in their own way.”

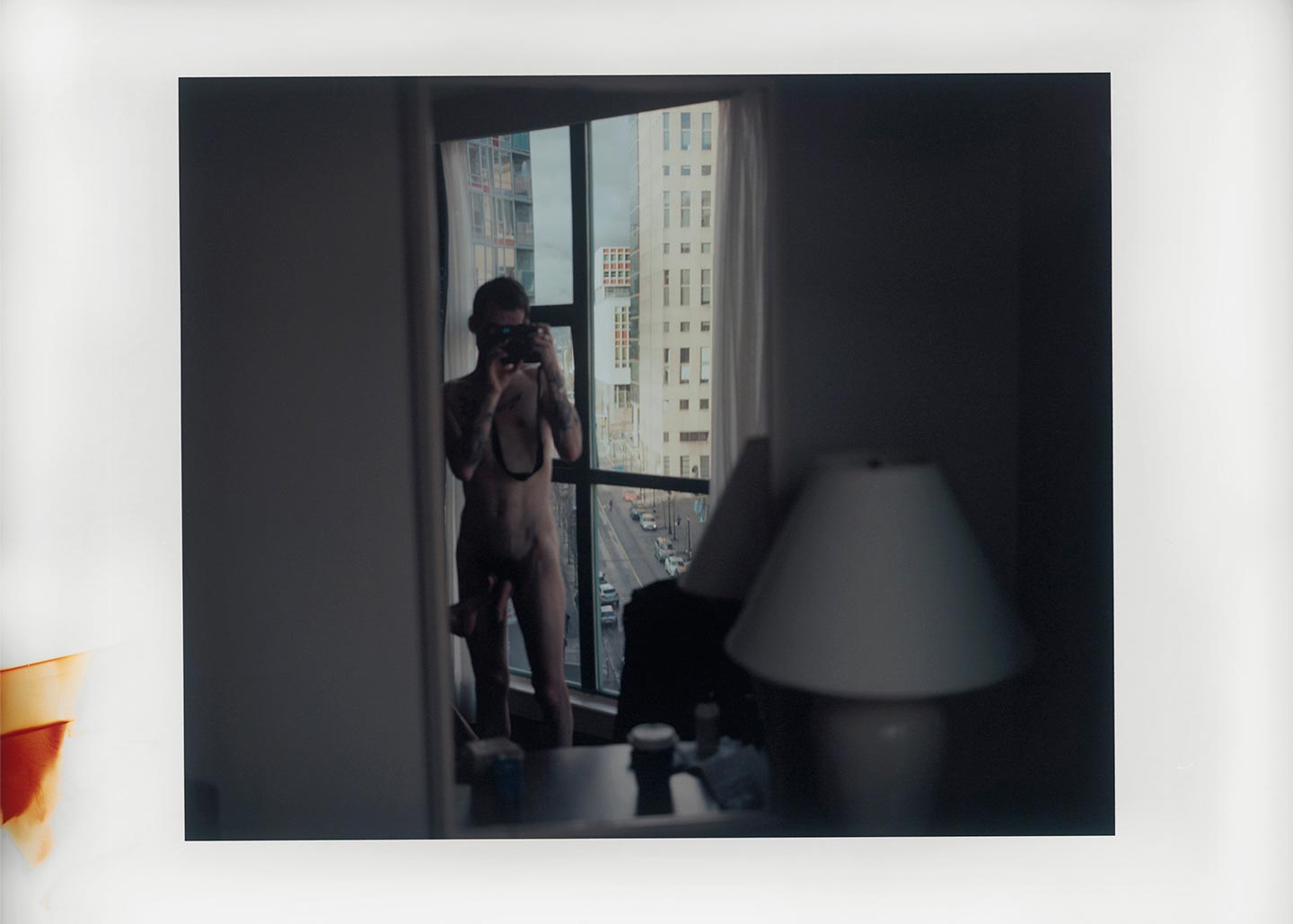

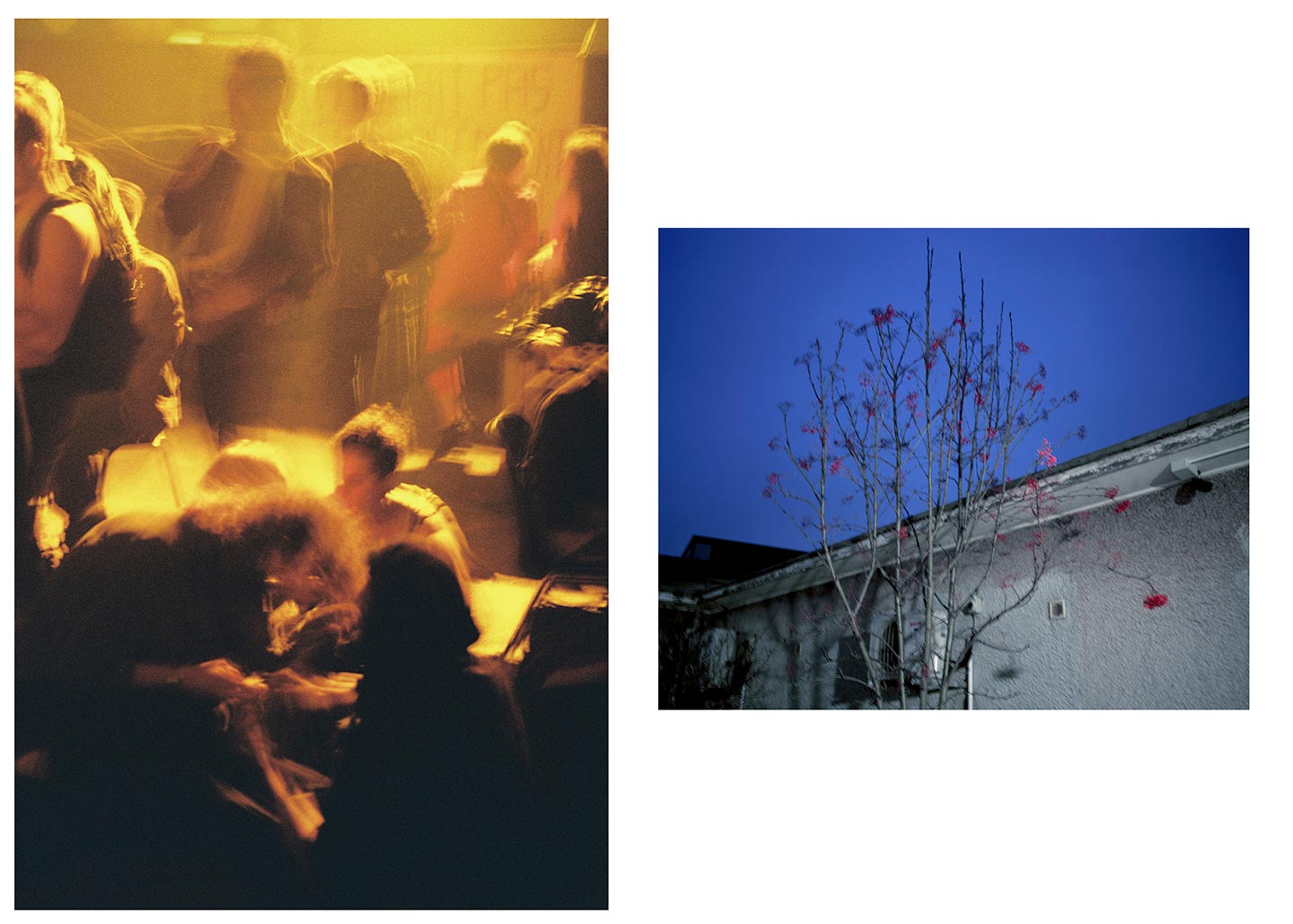

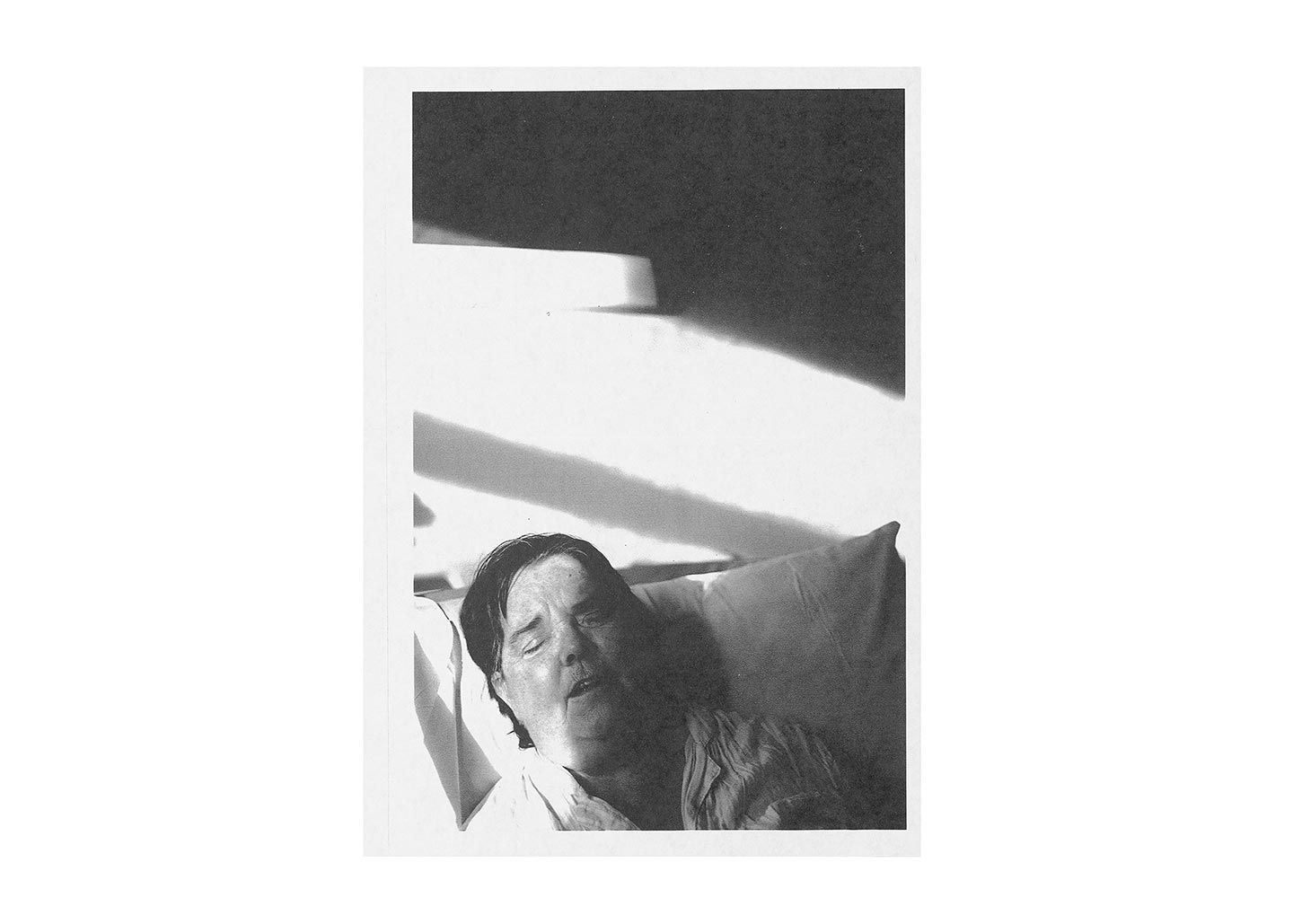

Dorje started working on Dream the End as his mother’s health deteriorated: “My own life gradually fell away as the demands of looking after her took over. This is something I think people in that position resist for as long as possible—it’s difficult to admit that you can’t keep all the plates spinning. Once it became clear that there was no longer room for anything else other than looking after mom, I began to take photographs, but only for myself. Like I said, at this point my life was pretty much falling apart, almost wholly of my own doing. Without wishing to defer responsibility, I responded to mom’s sickness to quite destructive effect—both to myself and those around me—making the situation far more complex and difficult to cope with than it might have been.”

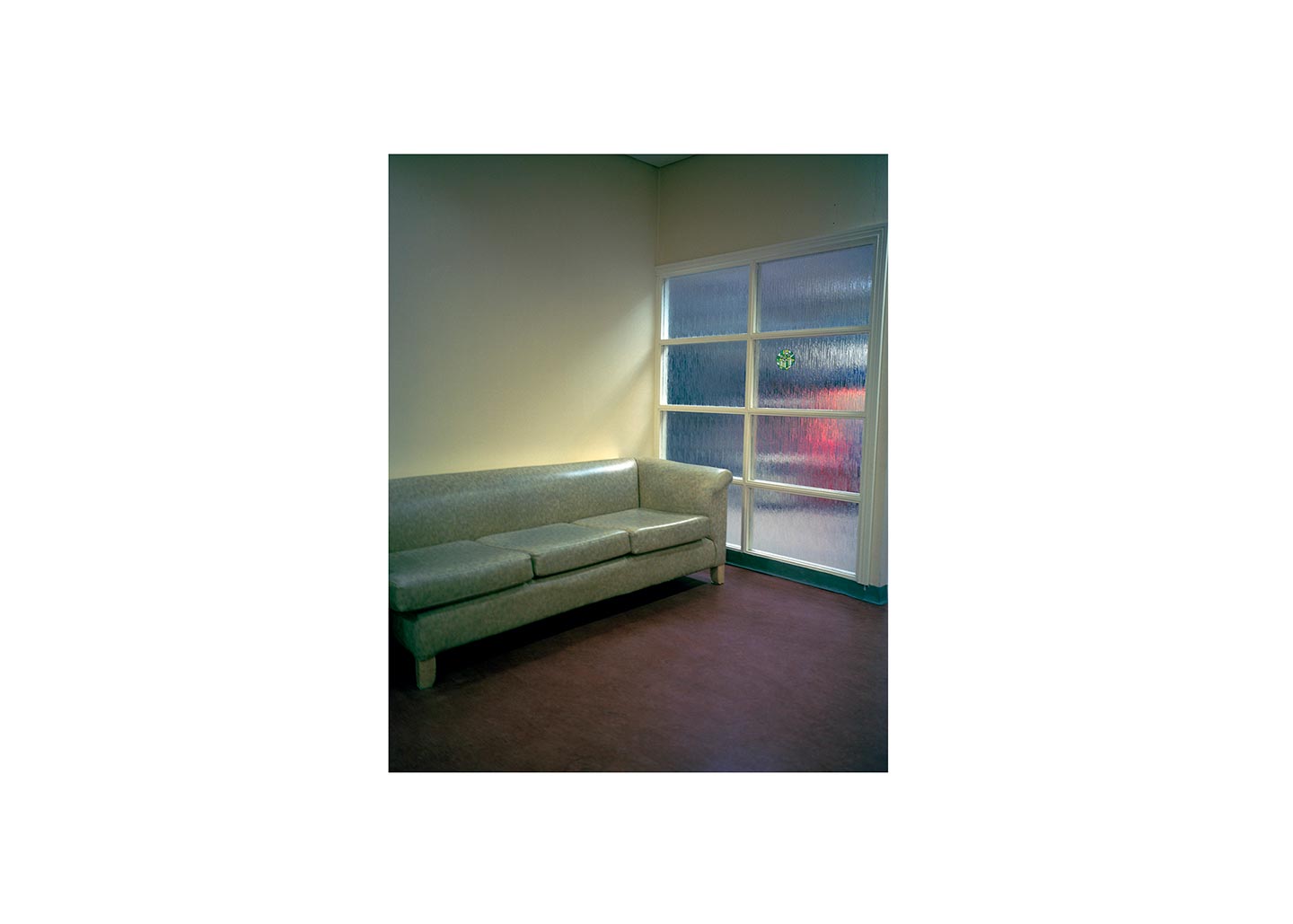

“I suppose my practice has always involved compulsively making images of my daily existence, but I really had no intention of making a work at that time. On one hand, I didn’t really know how I felt about mediating an experience as strange as the one my mom and I were going through together; and on the other, I felt I was sure that it had been done before, many times. The only thing I knew was that I wanted to avoid sentimentality in the images I was making. While not without moments of beauty and laughter, what was happening to mom was sad, brutal, and unfair, and I wanted to remember it as such.”

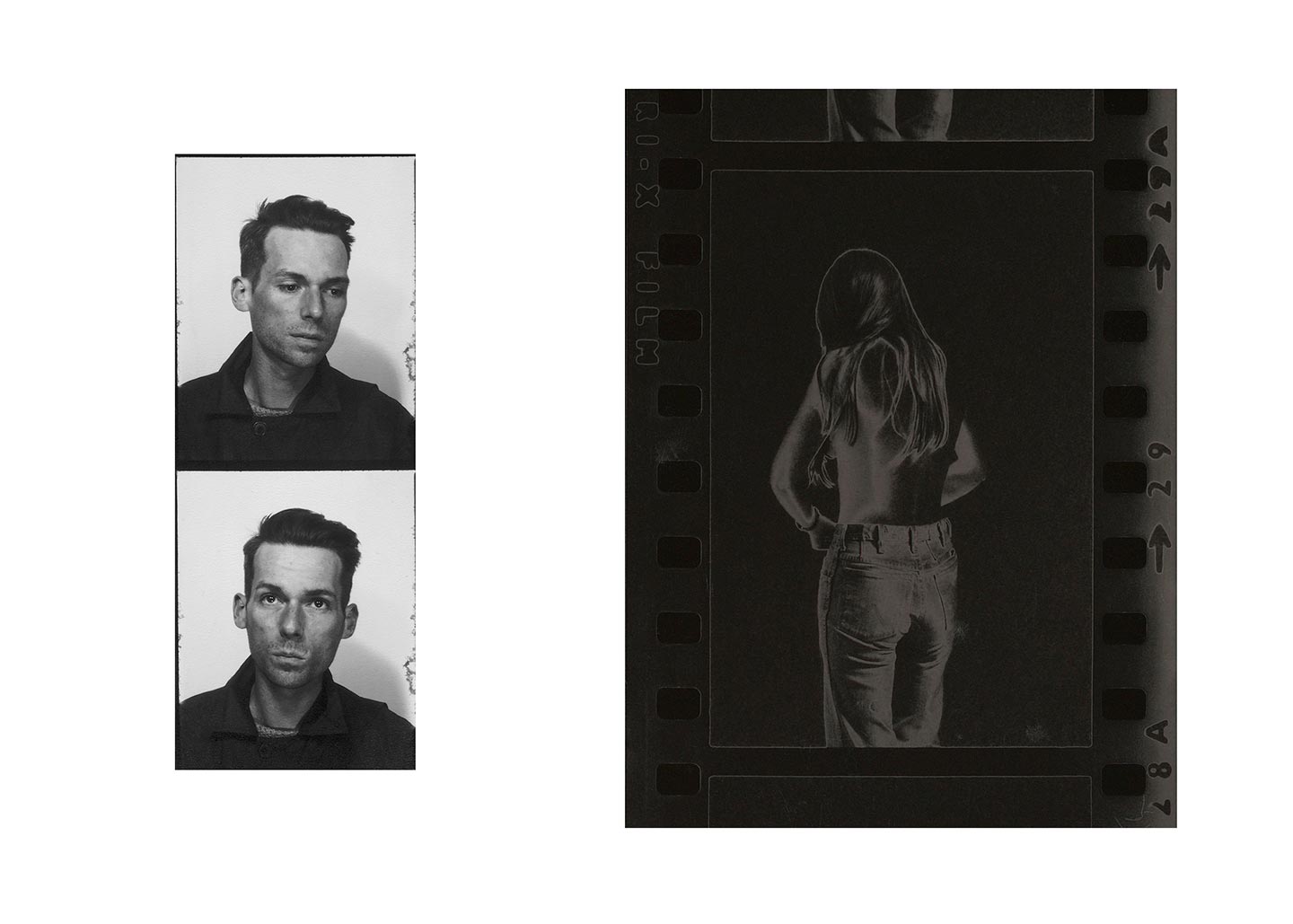

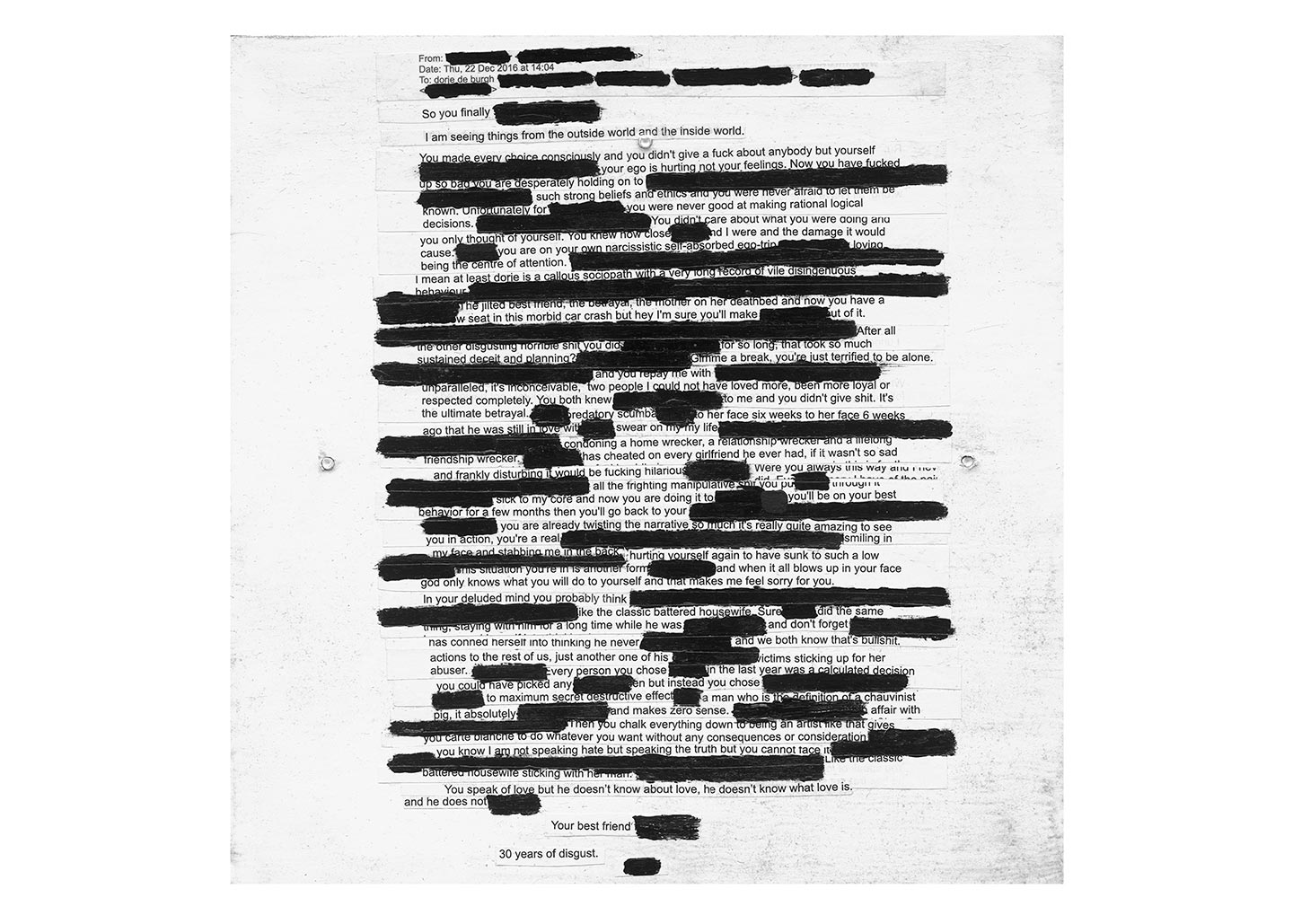

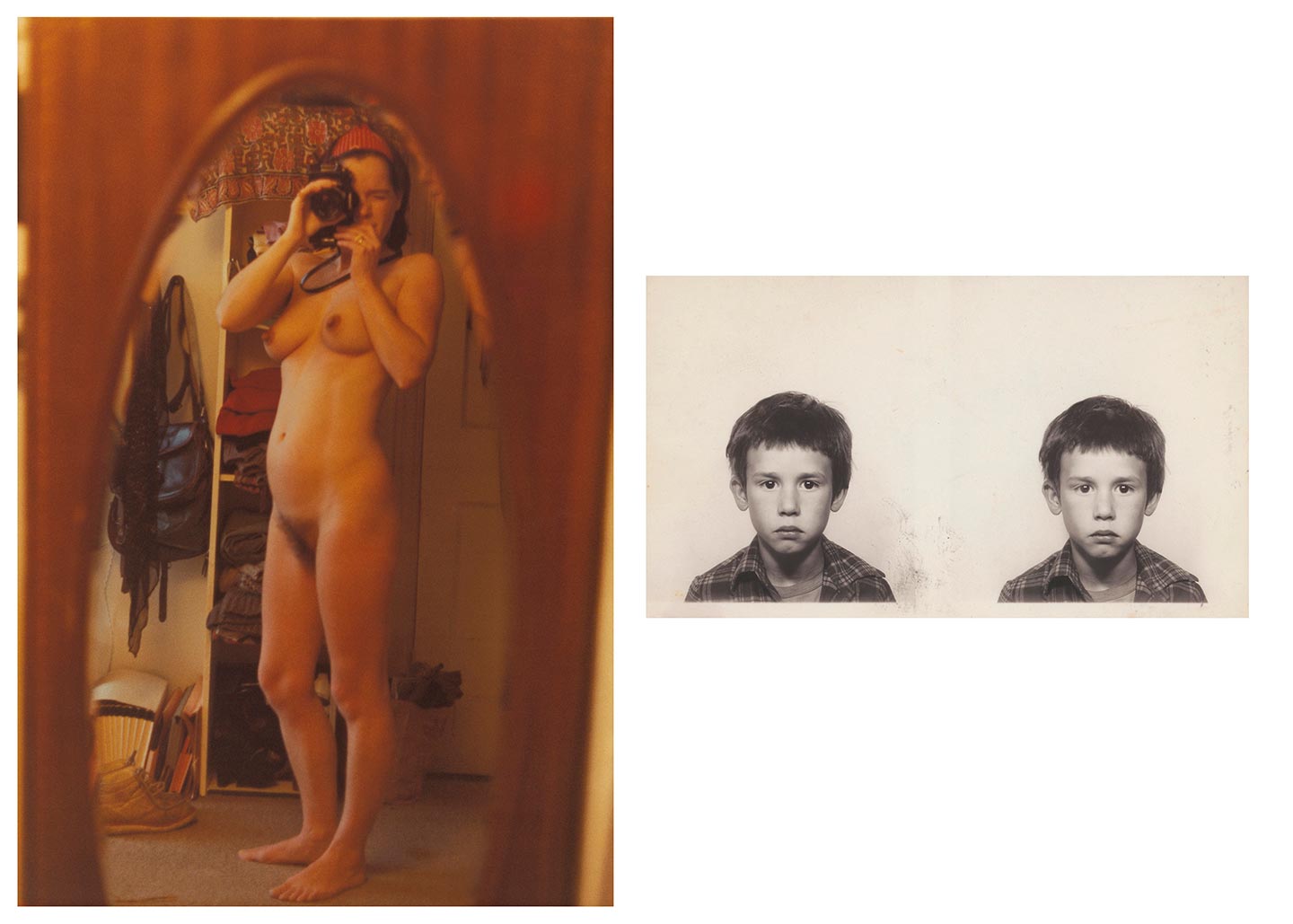

“After her death two things happened. First, I found a huge box of photographs from mom’s life before I was born that I had never known existed—documents of another life, another person. Then the Master’s program that I had been enrolled in for the last two and a half years gently suggested that it might be best if I wrote my final thesis before the end of the summer, to save me more years of fees that I absolutely could not afford. So I ended up spending the next four months writing a pretty demented, grief-stricken, psychoanalytic analysis of what it means to photograph death, using my own images as a case study, in-between all the awful bureaucracy, clearing out and life-dismantling that inevitably has to happen after someone dies.”

“The first half of that text was written on a typewriter in some masochistic attempt at a performative reflection of indexicality as I analyzed hand-printed analogue photographs, and the second half in the format of a word document as I compared those film photos with images and videos made on my phone. The goal was to try to come to some kind of conclusion as to what photographs—in their now wholly ubiquitous, democratized and dematerialized form—can possibly mean in regard to trace, death, loss and memory. What would Barthes make of the iCloud, basically. I’m not sure how successful I was but in the process of making it I realized how little I actually knew about my mom, my family, and my own history. And it dawned on me that I will now probably never know the full story. I had so many images but seemingly an equal measure of secrets and unanswered questions. I felt that a work might develop from this—maybe less about death in and of itself, but more about the questions death has the potential to provoke. I set about trying to make a duet of sorts, a collaboration between me and mom: some kind of semi-imagined mapping of our relationship, lives, and shared history, and of course its end.”

Dorje had several references in mind while working on Dream the End: “I suppose I drew from the work of artists and writers I’ve always loved and admired—those that mine their own lives and histories to try to better understand things, such as David Wojnarowicz, Eileen Myles, Wolfgang Tillmans, JH Engström, Brad Phillips, Maggie Nelson and Leigh Ledare. The work of painter and psychoanalyst Bracha Ettinger also played a massive role in my conceptual framing. And my partner Doireann who, aside from keeping me sane throughout and making brilliant theatre, also taught me the value of Truth in art.”

Ideally, Dorje hopes viewers can connect with his work personally. “I suppose I’m trying—with what I hope is a balance of honesty and ambiguity—to open up a space between the specifics of my story and the stories of others in which the two can connect, and maybe create something new. There’s also an element of the work that’s directly influenced by the research that led to it, one concerned with the medium, auratics and modes of delivery. This is as much for myself as anything else. But of course I hope it’s in there in some communicable form. The thing that has kept me returning to photography after all these years is that I still struggle to understand it.”

Before Dream the End, Dorje has made two projects called Things Fall Apart and Nothing Lasts Forever. “The first was about youth, the second about the the future, and now Dream the End is about the ultimate long goodbye. Embarrassingly enough all my projects unimaginatively lean towards a certain theme. I obviously have some kind of obsession with endings and their futile arrest, which kind of makes sense for a photographer given the particularities of the medium. A friend once told me that everyone he knows who takes photos obsessively either wears glasses or made models as a kid. His theory was that the drive was either about vision or control, depending on which side of the fence you fell. I didn’t wear glasses then but I do now, and I basically did nothing else but build World War II models during my pre-teen years. From that you can draw your own, probably tragic, conclusions.”

The first major influence on his photography was writer J. G. Ballard: “His writing totally dominated my decidedly pessimistic world-view for the duration of my twenties, in both visual and atmospheric terms. Photographically, JH Engström has been the artist I return to the most—how he manages to balance dissonance and harmony is baffling masterful, and I never get tired of getting lost in his world. In regard to the rigorous application of heavy theory while still making visually stunning work, Leigh Ledare is, I believe, absolutely the smartest guy in the room. But I wouldn’t have survived the last three years without Eileen Myles.” Some of Dorje’s favorite contemporary photographers are “Marco Marzocchi, Salvi Danés and Luc Delahaye, and I just got turned on to the work of Harry Gruyaert—his stuff is wild! Plus early Paul Graham. And of course, Michael Schmidt.” The last photobook he bought was Oyster by Marco Marzocchi and A Les 8 al Bar Eusebi by Salvi Danés; the next he’d like to buy is Montöristen by Carl-Mikael Ström.

Dorje’s three words for photography are:

Death. Loss. Memory.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2024