Inside Russia’s Closed Cities

36 year-old Russian photographer Sergey Novikov introduces us to ZATO, a project focused on the quite incredible reality of Russia’s secret cities.

Hello Sergey, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I see photography as a tool to explore social, economical and political conditions, a medium to study urban environments. Through either documentary or constructed images, photography points out at the current state of things in society. You can say that my photo projects are the product of my reflections on the world.

Your series ZATO is inspired by Russia’s closed cities. But what are closed cities exactly?

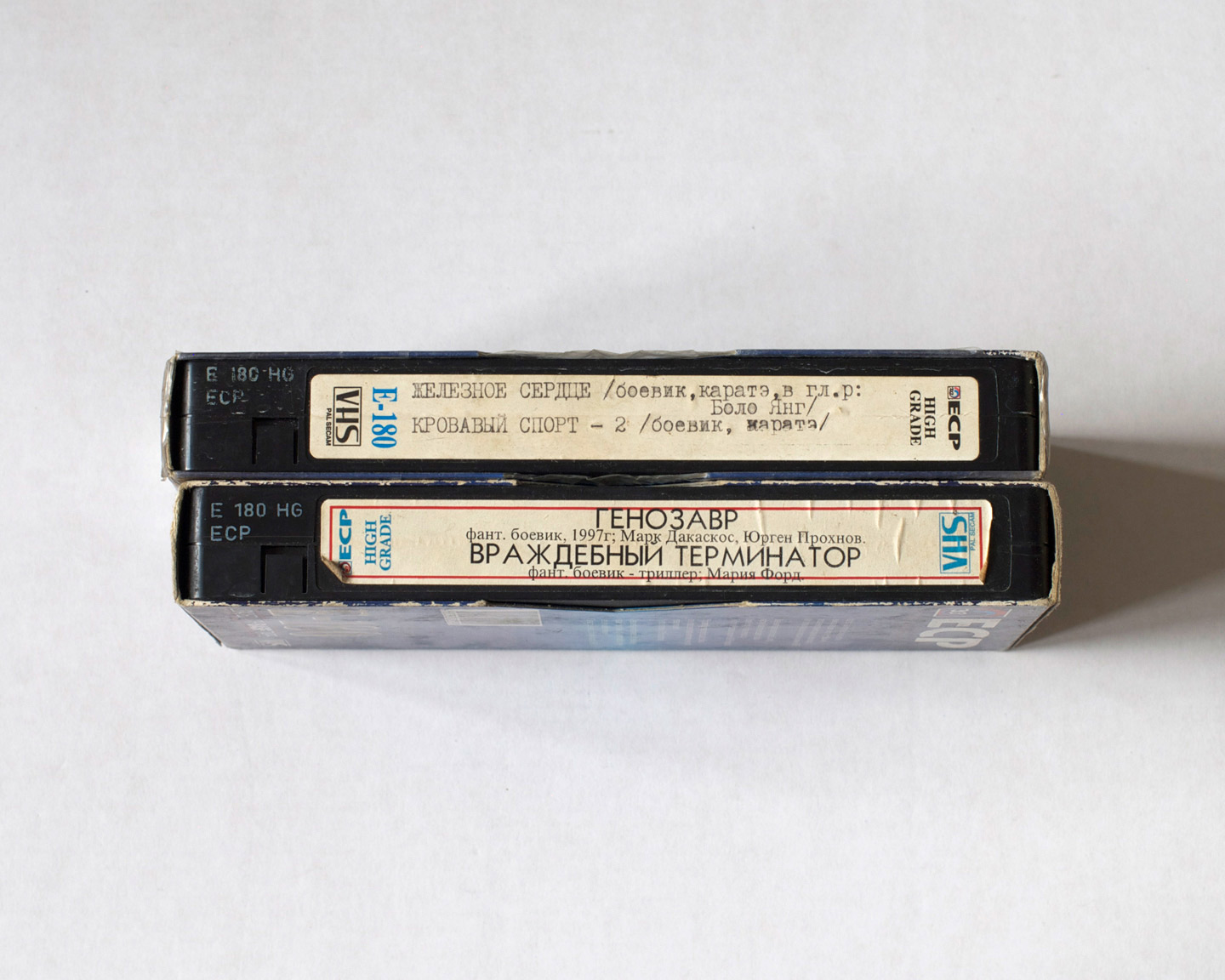

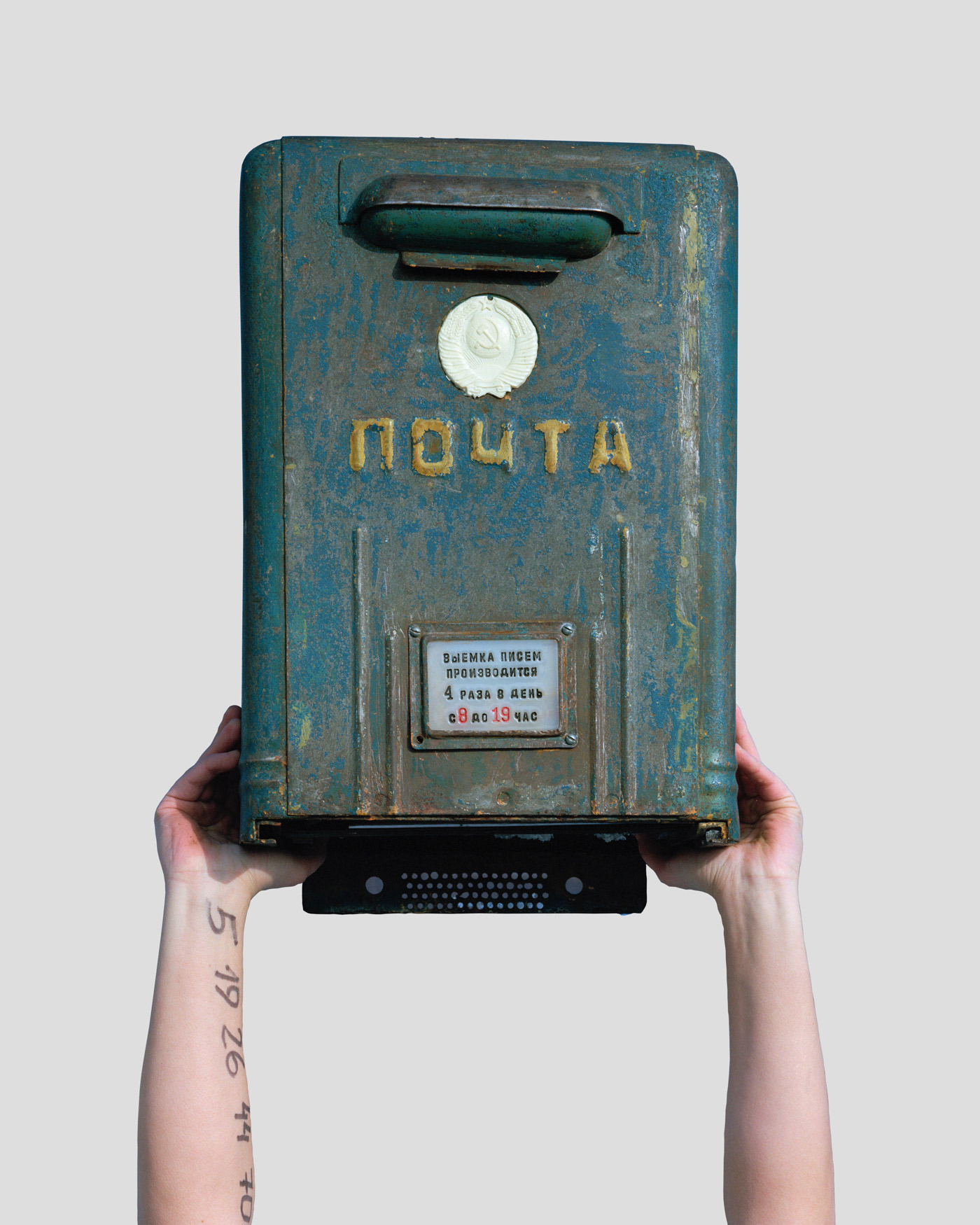

Closed cities (known in Russia as ZATOs) were established in the Soviet Union from the 1940s to serve as nuclear weapon development or disposal sites, and were home to the navy and missile forces. These cities were not on any maps, had encrypted names and were called “mailboxes” by analogy with the classified institutes or secret manufacturing facilities situated in them. The residents were told not to mention their place of living, but to use the name of the nearest major city instead.

With the collapse of the Soviet state, another life began for these towns: they ceased to be secret. Nevertheless, borders remained closed for “outsiders”; the good life conditions the residents enjoy in these cities – budget subsidies, low crime rates, high-level medicine and social services – led them to raise the issue of whether to retain the barriers.

Today, there are 41 closed cities in Russia with a total of 1,2 million inhabitants; more than 100,000 live in the biggest of them. To enter into a closed city you need a pass, typically an invitation from a near relative. Recent polls among the residents revealed that the majority of people are still against a radical change of territorial policy.

Why did you decide to make this project? What were your main intentions behind it?

The first time I was in a closed town, I was surprised that such a reality can even exist in our country today. It seemed to be some kind of Soviet artifact, but there was something more about it… A checkpoint at the entrance to the city, an atmosphere of mystery – residents believe that their walls keep important state secrets. As I worked on it, the main focus of the project shifted from my attempt to analyze the existence of these towns to studying the citizen’s desire to stay in a preserved and isolated area. Last October, the Ministry for Economic Development prepared a draft law to open 6 of the 41 closed cities on January 1, 2016. The news came as a bombshell and caused tremendous indignation among the authorities and residents.

A closed city can be considered more generally as a miniature of the entire Russia: it possesses the same tendency to self-isolation. ZATO is also about the absurd idea of achieving complete safety and isolation: as protecteed as these cities are, there are holes in the walls, and a pass to enter can be bought with some efforts. That’s why many images are evidently directed, and a bit grotesque.

The images of the series were not actually shot in the closed cities but are staged photographs. Can you talk a bit about the scenes you created, and the narrative you wanted to build through the images?

First of all, I didn’t even think about going to a closed city and shooting there illegally, especially not with my bulky large-format camera. Shooting in those towns can be the subject of talks at the local Federal Security Service office; it is prohibited even in the days of mobile photography.

Right now I am very interested in staged photography and visualizing scenes of the closed cities that are kept in my memory or that represent social media conversations between the cities’ residents. Some of the staged pictures are quite anchored to reality, others are more the result of my imagination, but they all allow to reflect on the lives of those who are inside the wall.

What is the content of the social media conversations you mentioned?

A lot of information about life in the closed cities can be obtained from social networks. Online, residents can talk more openly about how to gain entry to the city (by hiding in a suitcase in the trunk of a car, for example), their fear of opening the walls, as well as fun things like searching for a foreign husband. Some of these stories will be included in the project’s book.

There’s another very important part of my project: I asked some photographers who live inside the closed cities to take for me pictures of the urban architecture and buildings [the photo right below is one example] just to show how these cities look from the inside.

What is the first thing you would do if you had access to a closed city?

Closed cities are not that different from a typical Russian city. They’re safer, the streets are little bit cleaner, and there are more Soviet artifacts around. Small businesses are not common: these cities receive substantial subsidies from the state budget, which constitues the main source of income for their economies.

I like to observe and study life’s routine and banality, so if I were in it would be interesting to talk to the locals, to listen to their opinions on the opening of the walls, to look at archival photographs and family albums. If the biggest of the closed cities, Seversk, was ever opened, I would visit the local museum to take a look at the letters written by the prisoners who have built these cities.

Did you have any specific reference or source(s) of inspiration while working on ZATO?

The phenomenon of closed territorial entities is not very common in either literature or the arts; at least, I didn’t find much on the topic. More generally, I like cinematography, and in particular the genre of mockumentary. I’m also a fan of the deliberately staged scenes from Roy Andersson’s films.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

I always loved early color photographers like William Eggleston, Bruce Davidson, Stephen Shore and Joel Sternfeld. I also appreciate the works of Jeff Wall and Martin Parr. Of the younger photographers, certainly Alec Soth, Laia Abril, Max Pinckers, Bryan Schutmaat and many others.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Atemporal. Boundary. Irony.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2023