Simon B. Thorpe Uses Toy Soldiers to Call the Media Out on Underreported Wars

What makes one conflict more newsworthy than another? This question is one of the main drives behind British photographer Simon Brann Thorpe‘s latest work Toy Soldiers.

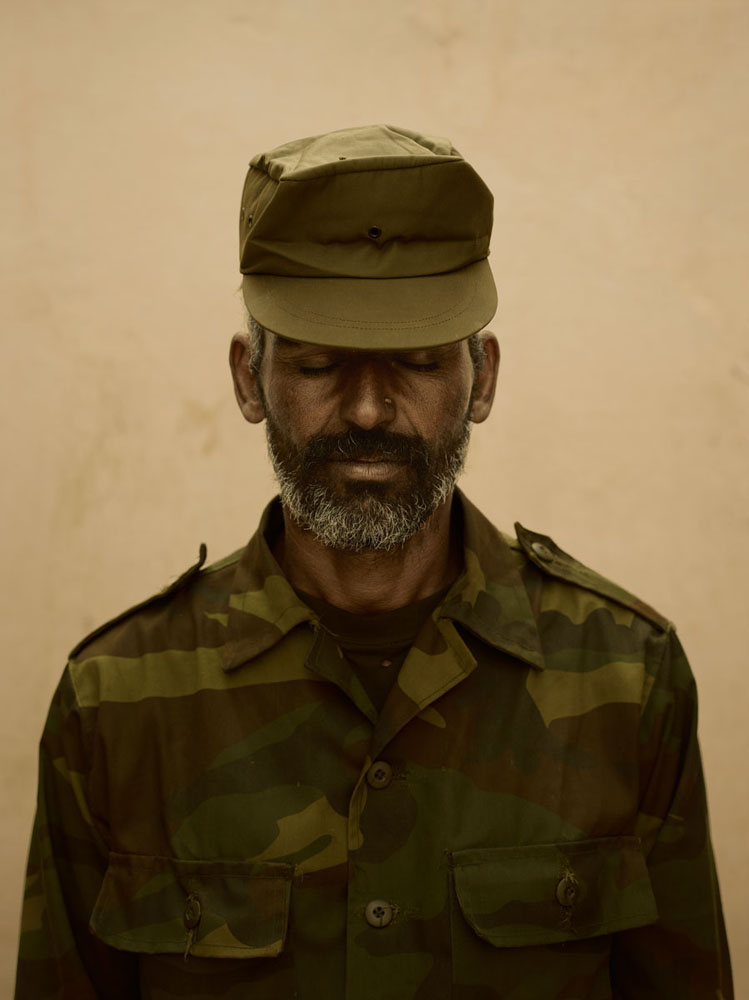

The project focuses on a conflict in the Sahara desert that has been going on for 40 years now, and nonetheless is largely ignored by Western media. In an attempt to draw attention on this forgotten conflict, Simon steered away from classic war imagery: instead, he collaborated with a military commander operating in the region to have real, human soldiers pose like toy soldiers.

The project has now become a book published by Dewi Lewis. Simon will be doing some book signing next 23 May at 2.30 PM at Photo London.

Hello Simon, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

My main area of exploration are narratives interlinking identity, landscape & conflict.

Where does your interest in the conflict in Western Sahara come from, in particular? And can you briefly introduce the history of this conflict to those who may not know about it?

I first travelled to the region in 2004 when I completed my first body of work on conflict and aftermath on the subject of civilian casualties of landmines and unexploded ordnance. I came away from that experience wondering why this conflict remains so invisible to the western world, and what makes one conflict more newsworthy than another in western media.

The conflict in Western Sahara is now in its 40th year and is no more visible than it was when it started. There are approximately 160,000 people still living in the same refugee camps established at the outbreak of the war in 1975; entire generations are growing up displaced and stuck in a wholly invisible cycle of perpetual non-resolution.

How did you get the idea to have the soldiers pose as toys?

When I decided to return to Western Sahara the only things I knew where that I wanted to work with the refugee soldiers in the conflict and I did not want to represent the situation in a traditional manner. The challenge became how to develop a new dialogue and resonance where graphic suffering, abject poverty or the purely exotic imagery of traditional reportage are replaced by beauty (in the landscape) and symbolic reference, but still contained within a very real conflict.

Toy Soldiers became a very powerful symbol relevant both to the conflict in Western Sahara and the absurd nature in which we glorify the horrors of war. The project enabled the creation of an arresting visual metaphor from which viewers can develop their own emotional, physical and political response to war and conflict, in relation to their own experience growing up and the implications of that experience when faced with the realization that the images do not in fact contain toy soldiers but real soldiers, real human beings.

What was your intent in creating Toy Soldiers? What are you trying to say with this body of work?

The Toy Soldiers narrative asks many questions. What makes one war more newsworthy than another? Why does the conflict in Western Sahara receive virtually zero coverage, despite the fact that three generations have now grown up and live as refugees since the war broke out 40 years ago? What does it take for the international community to engage with conflict resolution?

Toy Soldiers is also a dialogue on how images of war are digested and consumed in a digital realm ravenous for content but short on attention spans, on the consequences of ubiquitous images of graphic suffering and their desensitizing effect to war brutalities together with the implications of the glorification of war through gaming and entertainment.

Can you talk a bit about how your collaboration with the soldiers go? Was it complicated to direct them, and were they happy to participate in your project?

The process of making contact with the military commander, gaining his trust in the credibility of the project, location scouting, story boarding, fund-raising for the project and pre-production took two years.

The military commander and soldiers where amazing and even though conceptual art is not really part of their culture all the soldiers are refugees and as such where able to personally identify with the concept.

Is there any of the images in the Toy Soldiers series that you consider more significant or are particularly fond of, and why?

The are some images which are obvious favorites on many levels but the book is where the project has become whole in its narrative and flow. Even now, after five years from concept to completion, the project keeps raising new questions and highlighting implications on many cultural, political and humanitarian levels.

Buy the Toy Soldiers book here.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024