The Unforgetting — Peter Watkins Uses Still Lifes to Travel through His Family History

British photographer Peter Watkins (born 1984) discusses The Unforgetting, a series of still lifes shot in black and white through which Peter explores the history of his family and his own, marked by the suicide of his mother when he was 8 years old.

Hello Peter, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

My interest in photography is deep-rooted, and goes back to childhood and my family’s reliance on photography as a documentary tool—so often used as a form of cataloguing or indexing memory. My interest in the relationship between photography and memory became more acute in the years following the death of my mother, where anecdotes and narratives found in the retelling of notable memories seemed to be so tightly bound with their corresponding photographs. The photographs of her became totemic, almost sacred objects.

In my use of photography as an artist I’m interested in the intersection between the photograph as document—the photograph’s inherently indexical relationship to the world—and the narrative possibilities of the vernacular; photography’s relationship to memory and its reconstruction through the visual language of photography, and searching for a sense of meaningfulness in the world, and my place within that through this visual language. I think photography is as much a tool for feeling as it is for thinking, and this is what keeps me interested in it as a primary means of artistic expression. We think that photography shows us what we already know, but it is precisely in the space between knowing and unknowing, in that false assumption of knowingness that things become tangible and more interesting.

What is The Unforgetting about, in particular?

The Unforgetting is my long-term project that I began around 5 years ago and looks at my German family history, and more specifically takes the sudden death of my mother to suicide when I was 8 years old as its subject.

Why did you decide to make The Unforgetting? What was your intent in creating this body of work?

You can say that in essence it is a coming-to-terms-with kind of project, one that has become quite fundamental to me, and indeed has been a highly personal undertaking. I started thinking about this project almost 10 years ago, following the death of my father. They say that the sudden loss of a loved one can often ignite a deep-rooted feeling for a loss that has happened years earlier, one that has perhaps been buried deep in the sub-conscious and not necessarily dealt with adequately at the time, and I think this is what happened to me. The death of my father encouraged me to think back to that shared trauma my family and I suffered following my mother’s supposed suicide—her drowning in the North Sea on the 15th February 1993.

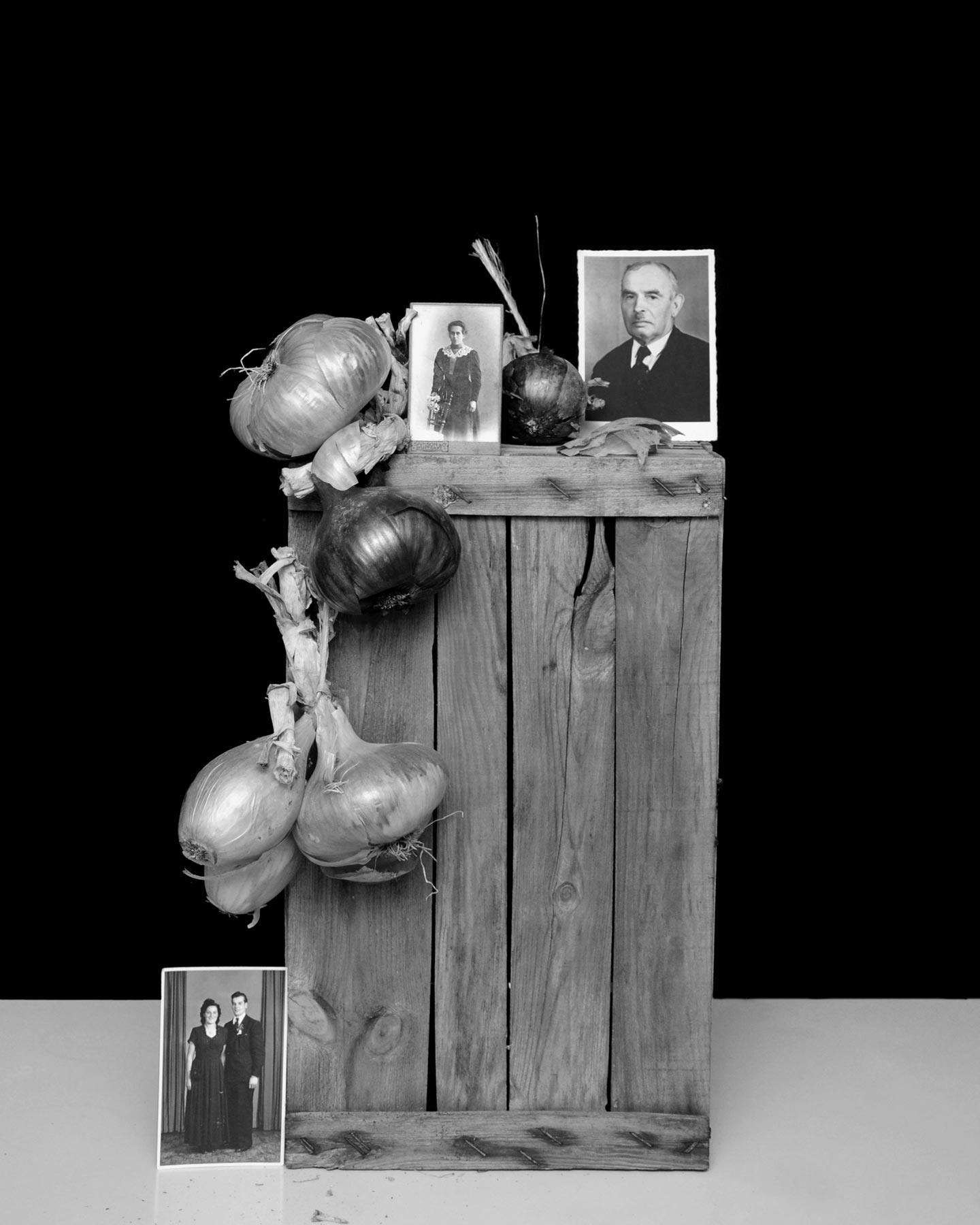

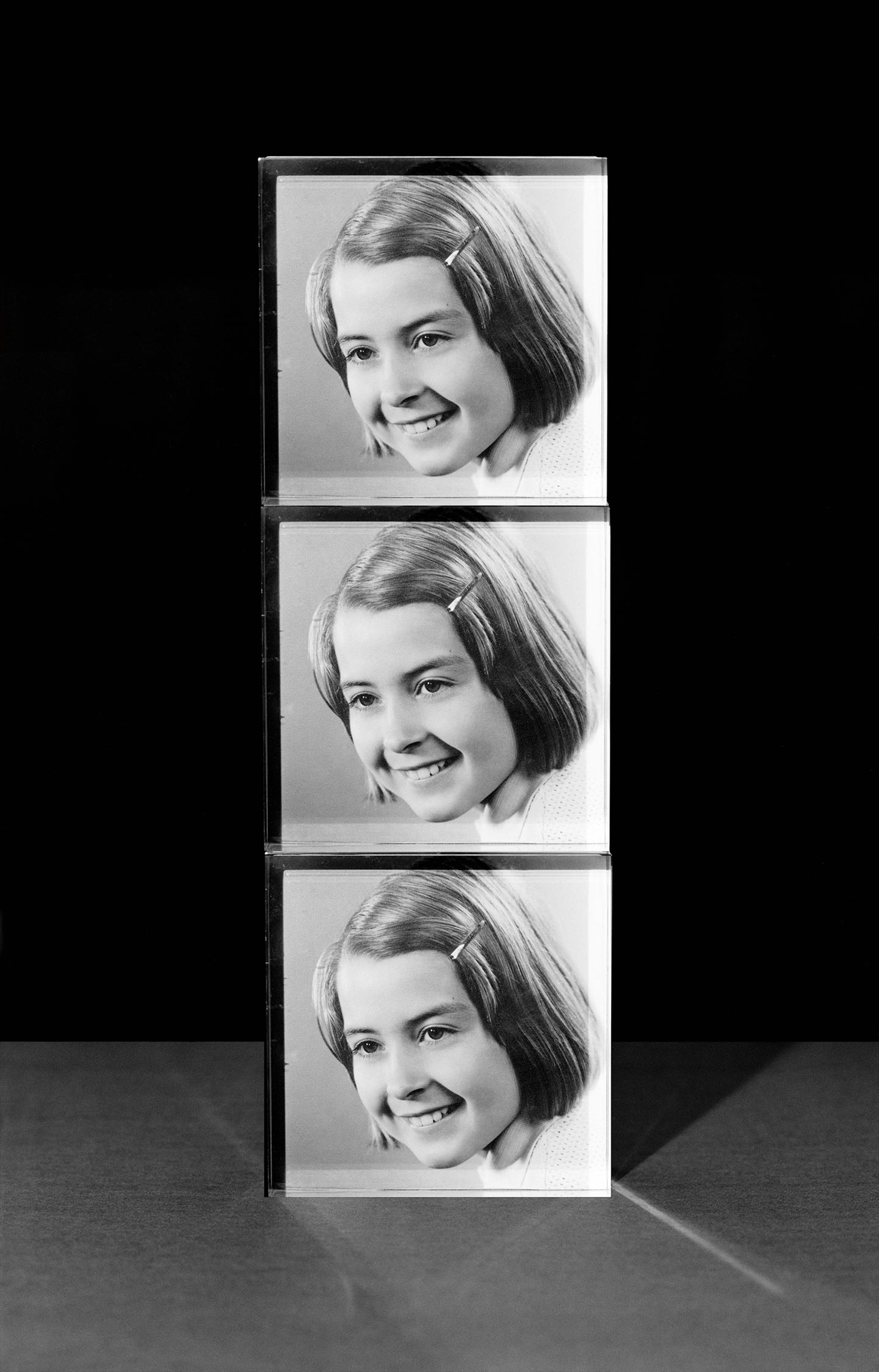

The project is made up of still life photographs of object assemblages, sometimes pairing personally meaningful things or domestic objects taken from my grandmother’s house with family photographs, which are arranged for the camera in a way that emphasizes the monumental. They are presented in Perspex boxes, a nod to museum displays, which further encourages the reading of them as monuments to memory. As well as these works, there are others that are more enigmatic in their reading, such as a hand horizontally suspending a collection of books mid-air, or a baptismal dress that floats mid-air, suspended in front of a net curtain.

Can you describe your approach to the work?

The work has seen several different iterations since I began. I started out quite differently, with more of a documentary approach, when I made a film consisting of interviews with family members about their memories of my mother’s death, and footage shot around the village where my mother grew up. In addition I visited the beach in Zandvoort, Netherlands, approximating where her body might have been found, and pointed my camera at the sea. I think I was attempting to go to the heart of the thing, that if I went there then things would make more sense, and I would substantiate the loss in some way. At the same time I was interested in that so called “ecstatic truth”, that Werner Herzog spoke of, and was seeking particularly in his early documentary films.

Having gone through this process, I decided to take quite a different approach to the work, using this footage as necessary groundwork, but discarding it almost completely from my vernacular. Everything seemed too literal to me, it was too sad and too sentimental and obvious somehow. I noticed from the filmed interviews that my family’s recollections had somehow blurred and merged into a kind of unified narrative, as if the passage of time had stripped away any sense of complexity and subjectivity from each individual’s experience. The realization of this conflation of memory influenced my new approach to the work. I decided to engage again with photography’s representational capacity, to investigate its parameters in relation to my own memory and that of others, and to use it to tell a sort of alternative family history. What I didn’t want was for the project to be an overtly sentimental study. Of course nostalgia would play its part, and I think I have exploited the nuances found in nostalgia, but I didn’t want the project to feel sentimental in the way that projects about this subject so often tend to feel. It was about finding a balance between thinking and feeling.

The Unforgetting consists of a series of still lifes depicting apparently ordinary objects. What do these objects represent for you?

The objects are chosen quite specifically for their connections to moments in my family history. They contain hidden narratives that go beyond their universal reading within the constellation or framework of the other works. I think that the works in this project are supporting one another; that there is a space between the images that each other image works in some way to reinforce or extrapolate. When there is something unclear, the entirety of the project comes to illuminate the singular images. Throughout the project I’m playing with presences and absences, lightness and weight, transparency and opacity, and in this case the absence of specificity, or the withholding of explaining away the personal complexity that these images contain leaves the viewer with space to project their own experiences and readings onto the work. Photography is after all such an inaccurate and subjective form of storytelling; space must be given to the viewer, and a balance must be found between overstating a certain reading, and leaving the space of meaning quite fluid. For example, the photograph of cans of Super 8 withhold the saturated images of happiness that they contain. They become reduced down to one, essential image, an image of unobtainable images, an analogy of course for the ineffability of memory.

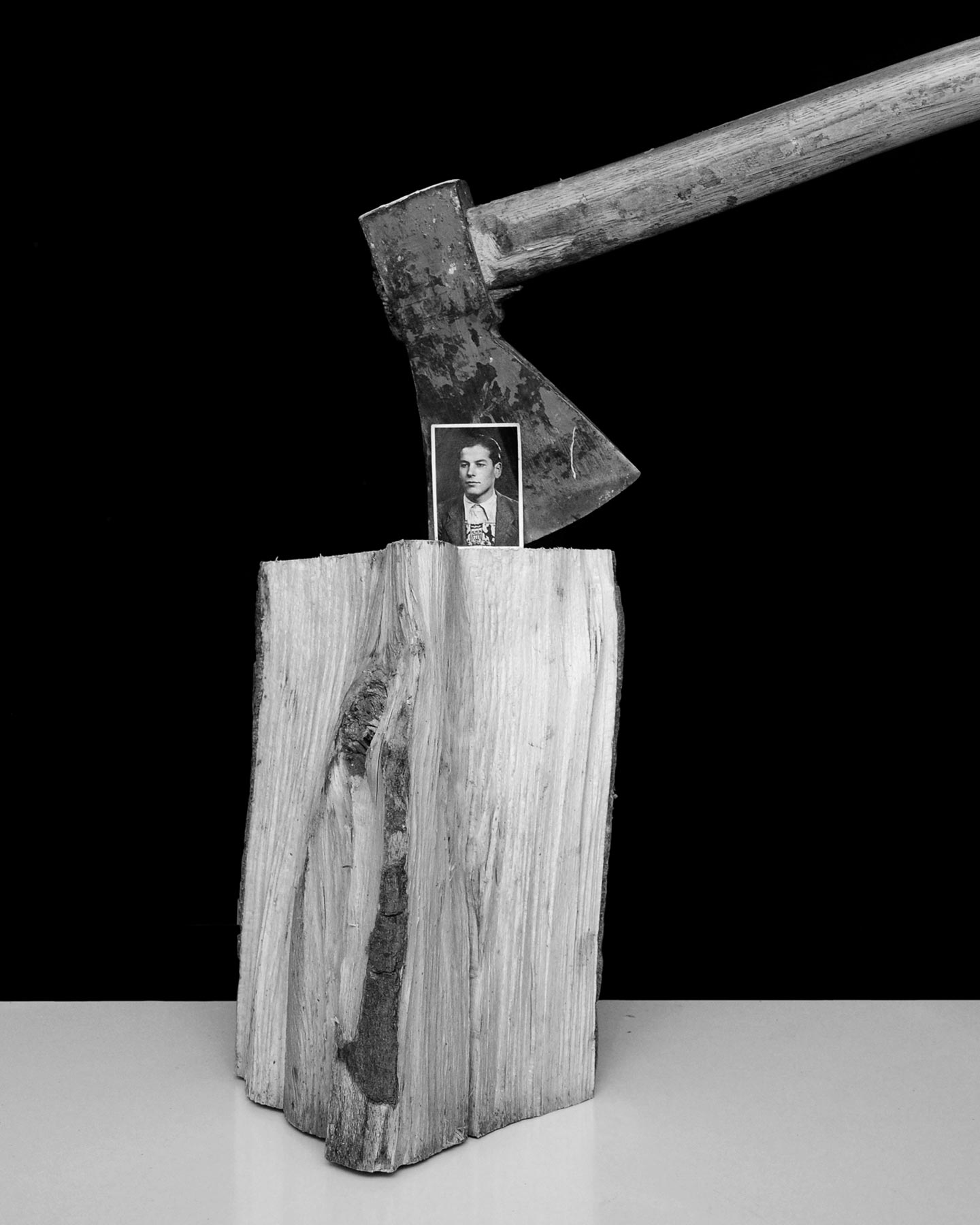

The glasses are called Roemer glasses and are a traditional German wine glass. The inscription carries the name of my Grandfather, and they were given to him for each year’s full attendance of choir practice, something he kept up his whole life, and each represent a milestone of time. He is also pictured as a young man in a small photograph rested against the blade of an axe. He passed away during the course of this project, but one of the last things we did together was to chop wood, and I had a sense at the time that this would be the last time we would carry out this repetitive, masculine activity together. I filmed the whole thing, and took a log away that appears in exhibitions of the work cast in concrete, and repeated three times. Wood is repeated throughout the project. For me it speaks of the folkloric, of Germany, of this German sense of ‘Heimat’, but also of the passing and splitting of time. In the photograph of my brother suspending a large piece of beech wood for the camera, the wood appears to flow from his arm, and there is a certain liquidity to the image, or sense of suspension, which I think is echoed in the photograph of the baptismal dress, and the books.

These objects are ordinary, as you say, but they come to constitute the debris of the departed, and contain within them much more complicated and integrated narratives that are important to me on a personal level. They are objects much like we all have, things that contain a history that we are able to sink ourselves into. Beyond that there are certain connections between these things that allow me to think about wider interconnected themes.

How do you hope viewers react to seeing The Unforgetting? Is there something in particular you wish comes across?

I think what is most important in terms of the viewer for this work is that there is enough space to project one’s own experiences. In a recent artist talk I gave in Liverpool in conversation with the curator of Open Eye Gallery, Thomas Dukes, I was struck by how thoughtful the audience had been, in terms of the connections they had found between the objects and the photographs within the show, and how open they felt they could be in discussing their own experiences in relation to the exhibition. I took great pleasure in this, as it confirmed to me some of the things I had hoped to occur, and in general gave me a sense that people engage with exhibitions with a certain clarity of mind, and a willingness and openness.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on The Unforgetting?

I was thinking about Werner Herzog, early on, about that idea of “ecstatic truth”; I was thinking about Chris Marker, specifically his essay film Sans Soleil, and Hitchcock’s Vertigo—the whole scene with the sawn sequoia tree. I was thinking about the vernacular aesthetic of Wim Wenders’ early black and white films, and the fall into colour as seen in his seminal Wings of Desire, but also a particular scene following a car crash in my favourite of his films, Kings of the Road. I was thinking about Tarkovsky. I was thinking about Roland Barthes, and the essential image of his mother that he so desperately sought, and Marcel Proust’s search for the impalpable essence of memory. I was also thinking about Sebald’s Austerlitz, and the way that objects, place, history and architecture played its part in the decoding and reconstituting of memory, and no doubt some other stuff along the way that right now I can’t remember myself.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

I take influence from such a broad spectrum of places, from film to literature, architecture, sculpture, the material nature of things.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

I’m interested in photography and look at many photographers, as we all do, all the time, but to select just a few is very difficult indeed—so I’ll select more than a few. One that may surprise you is Wolfgang Tillmans, who has been a touchstone for me for several years, although I don’t think you will see that influence directly in my work. What I admire about him is the totality of his “project”. That his work is the project. Everything is part of a greater whole, meaning he doesn’t necessarily work on a specific project, or divide his work up as such—although he may do this in the form of a book or in an exhibition that have moments of clarity and focus in certain parts—but the work is all tied together, and is ever evolving… It feels like his work is liquid, and although on the surface it can appear at first glance random, his constellations of photographs actually adhere to quite organised rules that he has self imposed, and within these systems he finds immense freedom. This has given him a framework to be able to work from in almost infinite permutations. His overarching philosophy of If One Thing Matters Everything Matters is what has really stayed with me, and it’s admirable.

Other work that I really love for many different reasons, or the ones that come to mind right now, I should say, are Collier Schorr, John Gossage, James Welling, Michael Schmidt, Masao Yamamoto, whose work I fell in love with last year when writing about it; John Divola, Onorato and Krebs, Darren Harvey-Regan, David Batchelor, Agata Madejska, Christian Patterson, Flemming Ove Bech, Aaron Hegert, Daniel Shea, Christopher Williams, Michael Etzensperger, Mårten Lange, Vivienne Sassen, Paul Kooiker, John Baldessari, Esther Teichmann, Taryn Simon, Tim Plamper, whose work is not exactly photography but starts with it, and I like it; Sophie Calle, Sarah Jones, and my partner Tereza Zelenkova – her work, attitude, intelligence and genuine interest in her subject as well as her ability to see the poetic connections between things are something I always aspire to and greatly admire.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Photography. Is. Dead.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024