‘The Blindest Man’ by Emily Graham Is Inspired by a Treasure Hunt for a Hidden Sculpture

The Blindest Man by 36 year-old British photographer Emily Graham is inspired by the real story of an anonymous author who in 1993 buried a golden sculpture somewhere in France, and released a book of clues for those who wanted to find it. “This unsolved mystery has obsessed treasure hunters ever since, and many continue to search” Emily explains. “A community fueled by competition has developed around it. Rumor, misinformation and red-herrings spread, confusing many individual routes of investigation, which lead to some extreme results: there are reports of digging at locations from Versailles to the foyer of a bank, of someone attempting to blow up a chapel in their search, of some hunters turning to eccentric methods in their solutions.” The author died in 2009, never revealing the place in which he buried the sculpture.

Of The Blindest Man Emily says that “I was less interested in creating a documentary about the hunt, than using the hunt as a narrative device or metaphor for a pursuit that has no answers and no ends. I also wanted to explore the hunters’ widely varied individual interpretations of the clues, and where this leads them. Many people thought this story would make a great documentary film, however it was exactly photography’s limitations that were interesting to me in trying to work with a subject such as this: I wanted to explore the dreams, fantasies and obsessions of individual searchers, the precarious nature of pursuit and failure, and in turn, explore photography’s own slippery relationship to truth, searching, interpretation, fantasy and obsession.”

Emily’s typical process for taking photographs is largely based on walking and wandering with a camera in her hand: “I usually go to places specifically to walk and make pictures, and I find myself going to locations with ideas in mind of what I might find, either from prior research, or from books that I’d read (often fiction) that were set in said places. I was looking for a framework for these wanderings, and started thinking about how much of what I photograph was influenced by what I had in mind that I was looking for. I started to think about these as scavenger hunts, if you will. From here I took a literal jump, and started researching real-life treasure hunts, thinking that perhaps I could use people’s search routes as arbitrary routes on which to make pictures. After a while I came across the story of this treasure hunt in France.”

Initially, Emily followed the players’ failed routes she had found online as a framework for making pictures, but then she started contacting some of the searchers and was fascinated by what they had to say: “One person has a spiritual reading of the quest, and through it her life has become imbued with signs. Another talks of being lost in the world of the hunt, in his day-dreams of being victorious and in trying to calculate solutions, in always being on the cusp of finding the thing, how it often takes him away from his time with his family and friends. Another person has raised a court case against the family of the author (who is now deceased), to halt the search: he posits that he has the correct solutions and the game is fraudulent. For me, this connects to the ways in which people respond to the world, the dreams and fantasies that individuals set out for themselves, and the difficulties and frustrations they experience in realizing them.”

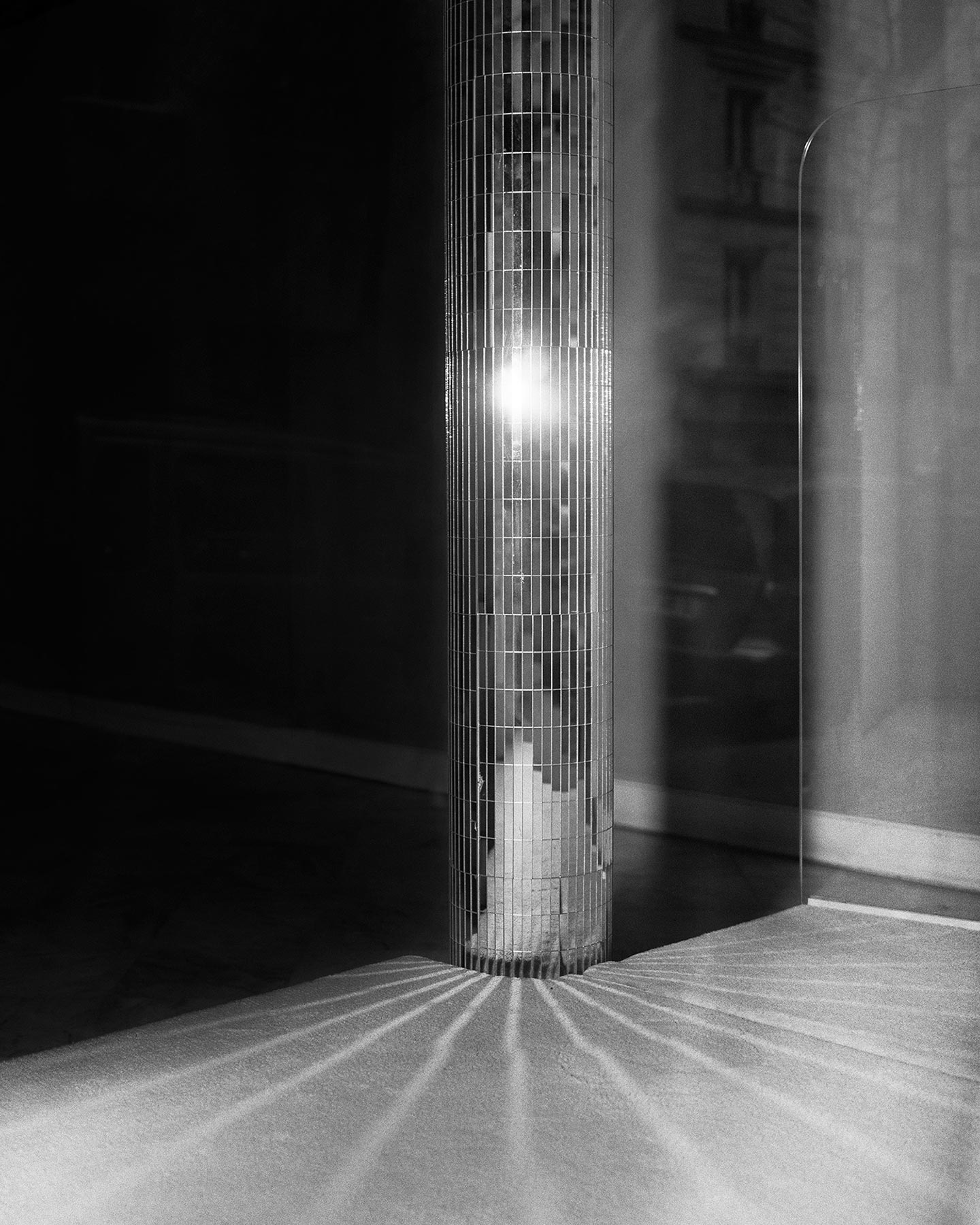

About the images, Emily says that “I was thinking about photographs as markers, clues, connectors, and thinking about how people read meaning into fairly ordinary scenarios that chime with what’s in their mind, become co-incidences. I walked around the suburbs of Paris, around forests in the east of France, through small towns and edgelands, looking for surreal details and markers, or scenes transformed by light to become strange or beautiful. The way I made the pictures was also influenced by this idea of obfuscation, of deliberately making things unclear using light and shadow within pictures to emphasize this sense of partiality. Along these routes I was also looking for pictures that could represent a sense of a never-ending unfulfilled quest, looked for symbols of looking, going in circles, not reaching a desired point, obscuring.”

Emily hopes that viewers can read The Blindest Man on two levels, “as a visual expression of the strange, wonderful, maddening world of the hunt rather than an attempt to communicate the details of it; and as a reflection on a very human experience of the allure of trying to reach that which is out of reach (here knowledge, treasure, the content of the image, the conclusive document) and the difficulties, sometimes madness of trying to reach it.”

Besides being a photographer, Emily has also worked as an editor, a festival director, a producer, a curator, “so I have always been looking at lots of different types of images and imagery, from the history of photography as an art form to more utilitarian/functional pictures. I really enjoy the multitude of forms and guises photography can take. I’m fascinated by the documentary image, and the tensions/difficulties of the document, but I’m also drawn towards more formal or aesthetic applications of photography. The first photobook I got a hold of was Richard Billingham’s Ray’s A Laugh—it was being sold off for £1 or so in my local library when I was a teenager—and I recall that having a big impact in the way that I thought about what photography could be. I also get a lot from looking at artists who are playful in their practice, like Laure Provost, Sophie Calle, John Baldessari (as much for his writing as for his artwork).” Some of her favorite contemporary photographers are Paul Graham, Jason Fulford, Stephen Shore, Gregory Halpern, Vivianne Sassen, Raymond Meeks and Vanessa Winship. The last photobook she bought was Slant by Aaron Schuman; the next she’d like to buy is I Walk Towards the Sun Which Is Always Going Down by Alan Huck.

Emily’s #threewordsforphotography are:

Play. Suggestion. Passport.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2023