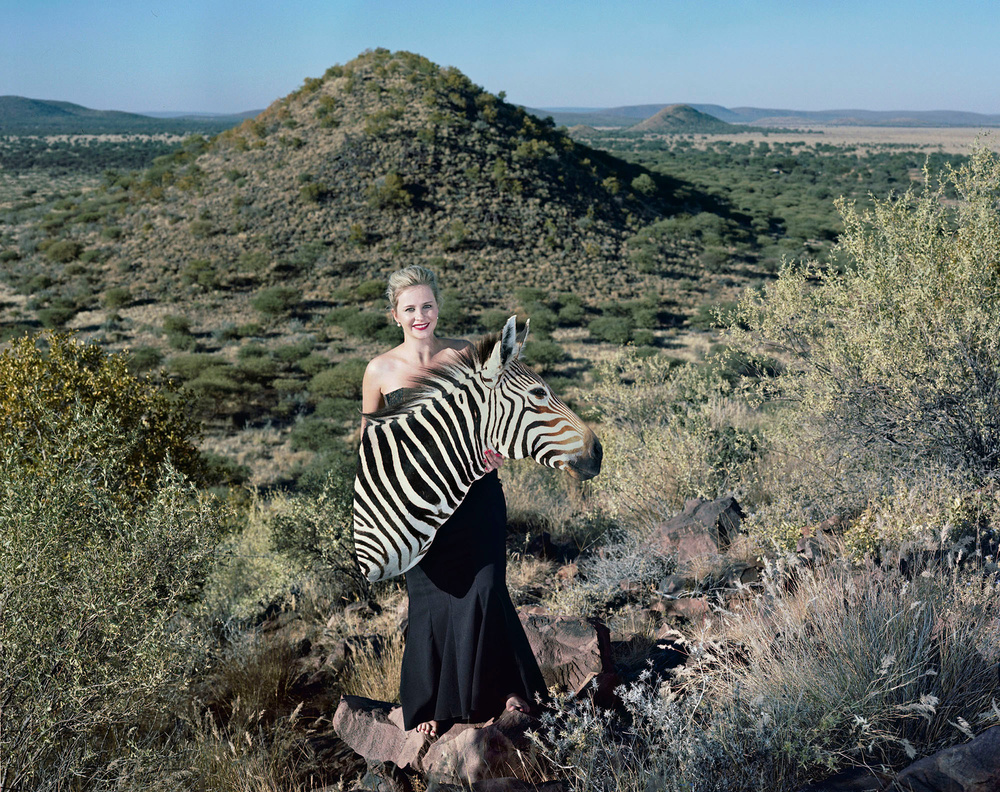

Subjective Trophies — Pierre Abensur Portrays Hunters Showing Off The Animals They Killed

We at FotoRoom and Pierre Abensur, a 55 year-old French photographer, are in a pickle: we think that killing an animal for sports is wrong, and hanging the stuffed head of the animal you killed on your wall, kind of creepy; Pierre, on the other hand, thinks this is a «moralistic, simplistic and rather elementary» way to look at hunting, which instead he sees as an ancestral practice with a beauty of its own. Whoever you agree with, Pierre’s staged portraits of hunters from all around the world, posing with their taxidermized trophies on the exact spot where the animals were killed, are undoubtedly arresting and well worth seeing (for a more elaborate idea of the photographer’s view on hunting, also have a read at his interview with us).

Hello Pierre, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

For a long time, long-term documentary photography has been the only good reason for me to be a photographer. At some point, the way I approach my subject matter has then evolved to become more conceptual.

Please introduce us to Subjective Trophies.

Subjective Trophies is a series of portraits of hunters posing in their most elegant outfits with their taxidermized trophies, on the spots in which the animals where killed. The photos were made with a 4×5 camera and a flash.

You shot the Subjective Trophies portraits all around the world, from Europe to Asia, from Africa to South America. How did you find your subjects?

I’ve used different networks: hunting federations, professional hunters, taxidermists, gunsmiths, tour operators, etc. I’ve spent many many nights on Internet to find them!

Horrifying as it is, the hunters look quite proud of their taxidermized animals. What do the ‘trophies’ represent for them? What kick do they get out of killing animals?

As someone who isn’t a hunter, I’m nonetheless surprised by the ‘horrifying’ adjective you used. Do you find ‘horrifying’ the taxidermized animals on display in natural history museums? A great part of those animals were certainly hunted down!

I am often asked whether I support hunting or not, and the answer is this is not the point of the work. Personally, I think that hunting—when practiced legally and ethically—isn’t responsible for the extinction of animal species, contrarily to intensive agriculture and farming. Today, the demographic growth and spatial expansion can hardly be supported without a direct human intervention on natural environments, unless we all move to live in metropolises and let the woods occupy the countryside.

To answer your question, the hunters’ relationship with their trophies varies greatly depending on their cultural background. For some, the trophies represent the souvenir of an exceptional hunt, of an intense emotion. For others, like the traditional hunters from West Africa, hunting is practiced in combination with complex esoteric rituals, so the taxidermized animals become proof of their magical powers. Finally, professional hunters sell the animals or show them off to attract clients.

Why are the hunters generally very well dressed in your portraits?

What the hunters wear is a reference to typical pictorial representations of the Romanticism. In that time, hunting was reserved for the nobles; those paintings showed aristocrats in sumptuous attire, posing in front of natural landscapes. Later hunting became more popular, and the taxidermized trophies made their appearances in less prestigious houses than the nobles’ castles. It’s the “social revenge” side of the trophies.

What inspired Subjective Trophies? Why did you decide to make this body of work and what themes did you want to address in these images?

I’ve inherited a small house in the village where I grew up, and there I reconnected with some old friends, a few of which have become hunters. I became interested in doing work on the practice of hunting, and during nights spent with these friends I started asking them questions about their own trophies. Their answers introduced me to the amazing history of hunting. Upon listening to their words, I started seeing something shared by the skins of the animals and their predators: I saw a form of mutual recognition, a tacit agreement, an ancestral obedience to the natural cycle of perpetuating a species.

The work can thus be interpreted in several ways based on different elements:

– The paradoxical love of the hunters for the animals. Listening most hunters speak about the natural and animal world convinces you that they have an authentic passion, much like that of bullfighters for bulls.

– The anthropological element of the evolution of hunting from a vital and ancestral practice into a sport which remains deeply anchored in its roots and tradition.

– The sociological aspect of how the higher social classes of the territories colonized by the Europeans have appropriated a practice introduced by the settlers.

– The connection between hunting and the totem cult: the sentiment of supremacy of one species that has the power to kill a life, and give it back in an artificial form.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Subjective Trophies?

Yes, some Fleming paintings showing a human subject in the foreground and a landscape in the background, from which they’re detached not only due to their prominent position, but also for different lighting.

How do you hope viewers react to Subjective Trophies, ideally?

I’d love for the viewers to go beyond the moralistic, simplistic and rather elementary view of hunting and consider the artistic approach of the work (which doesn’t mean that everyone should like it!).

What have been the main influences on your photography?

The first books published by Magnum Photos are like Bibles for me, and the photographers who belong to the agency the Gods of Olympus!

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Daniel Berehulak, Andreas Gursky, Frédéric Brenner, Taryn Simon, Yann Gross, and many others.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Composition. Frame. Instant.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2023