The Rio You Didn’t Know Existed — Vincent Catala Represents the City Beyond Clichés

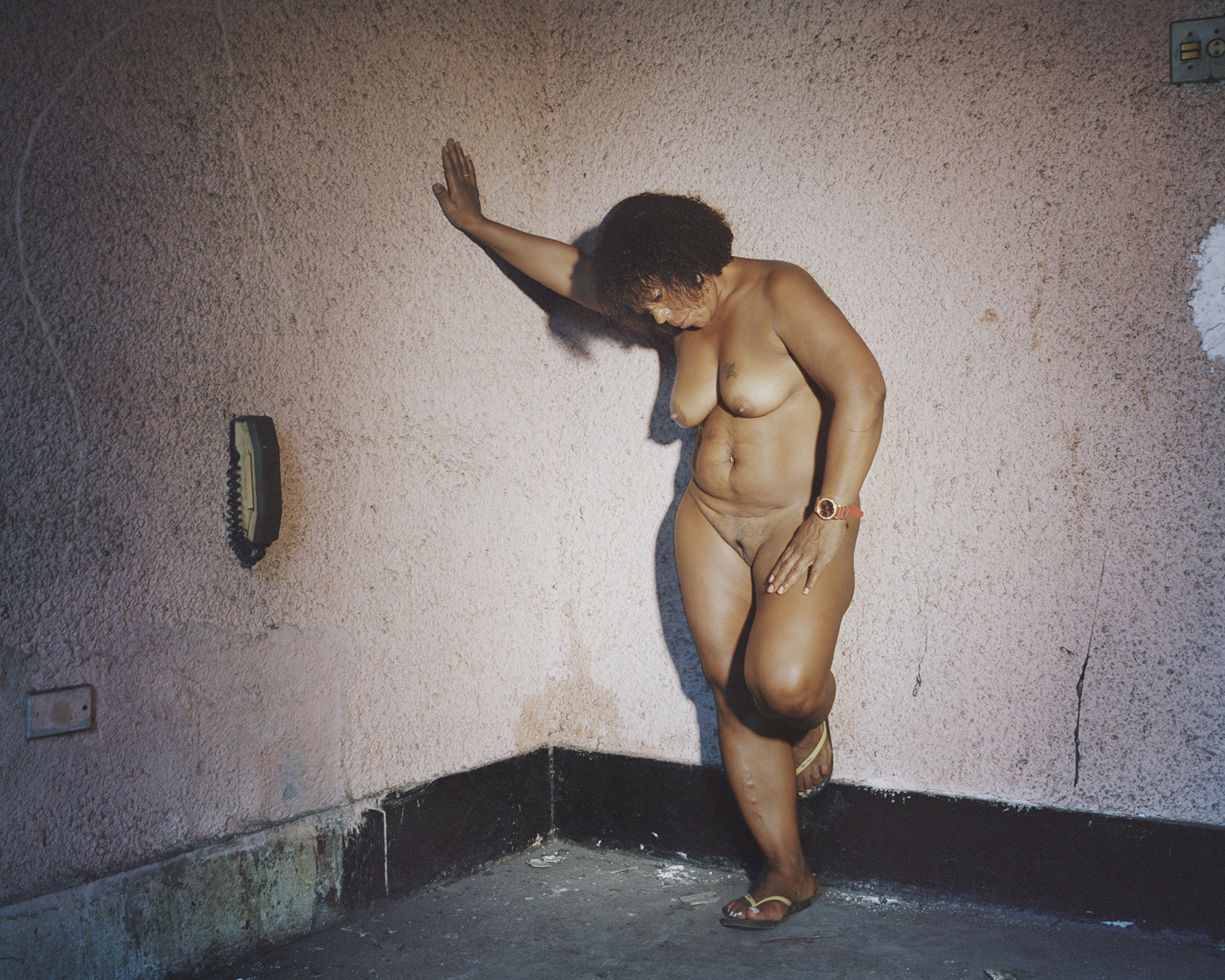

We’re used to think of Rio de Janeiro, one of the major cities in Brazil, as an energetic, kaleidoscopic place where the sun always shines. With his new series Rio, Rivage Intérieur [tr. Rio, Inner Shore], a mix of landscape photographs and environmental portraits, French but Brazil-based photographer Vincent Catala, a member of Agence VU, offers a more intimate, gloomier look at the city, focusing in particular on the broad area between the beaches and the favelas that you will hardly find in tourist brochures, or hear of in the news.

Hello Vincent, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I’m particularly interested in the relationship between the individual and his/her environment, be it urban or not. I think it creates space for a reflection on our relationship with the other and the world, and on ourselves at the same time. I use this approach in my commissioned works as well, but it’s in my personal projects that I can better develop this research.

Please introduce us to Rio, Rivage Intérieur.

I started this work when I moved to Rio in 2013, and it’s almost done now. As suggested by the title, the project creates a dialog between the public reality of the city and the intimate world of its inhabitants.

I photographed the city in a straight, precise way. This is the Rio in which I’ve lived and evolved, far from the double cliche of the well-known tourist neighborhoods on one hand, and the favelas on the other. Between these two extremes, there’s an enormous space which equals to about 70% of the city and its population. Its identity seems uncertain; it’s almost as if it was simply decorative. It comprises more or less scattered residential complexes, wastelands, empty areas, silence and lonely individuals; but it doesn’t matter how big it is, it’s still very far away from the common representation of Rio de Janeiro! This produces two reactions in me. The first one is to try to understand and appropriate my environment through photography. The second is to discover myself: the feelings of solitude and loss of references I perceive create the conditions for a personal reflection. In this regard, despite using very precise data and working a lot on location, Rio wasn’t the subject but the framework, maybe even just the pretext to make the project.

What was your main intent in creating this body of work?

I’ve had the opportunity to work on personal projects in the past, most notably in Rio from 2008 to 2009, and then in Jordan during an artist residency. These were great experiences, but I always had the feeling that I didn’t have enough time to complete the work I was doing. Since the start of this new project, I meant to give myself the absolute freedom to make work that was as personal as possible. I have to say I didn’t really realize how much sacrifice achieving this goal was going to take… But from the very beginning I told myself: «Go to the bottom of it. Maybe you won’t do a masterpiece that will be remembered by future generations, but it doesn’t matter. What’s important is that in ten years, you will be still proud of it». My commitment and my way of looking were completely honest.

When did you move to Rio de Janeiro, and how did your view on the city change since relocating?

I came to Rio for the first time in 2008. Over the following two years, during which I flied to Paris and back three or four times, I created my first personal work, Jane, La Nuit Tombe. It was the story of a prostitute who agreed to me following her at night right before disappearing. I looked for her for the next 18 months, but I’ve never found her again. At that time, I met and fell in love with Silvia, a woman from Cuba based in Brazil. After a while she followed me to Paris, then I came back to Rio with her; we broke up a few months ago. I’m mentioning this because, in a way, Rio, Rivage Interieur translates into images the deterioration of this relationship—the doubts, the solitude and the confusion that come with every breakup.

The recurring theme of the search—for Jane first, then for myself—made me look at Rio in a unique way. It’s as if the city was an enormous investigation field, the perimeter of a constant and voluntary wandering. But after all the years I’ve spent in Rio I’ve also become very familiar with the idea of agglomeration. I don’t really consider myself French anymore; it’s without a doubt in Paris that I would feel like a stranger now. So, did my view on Rio change? Not really. This city exerts a strong power of illusion that you perceive quite soon, I think. The reality you experience is nothing but the one you imagine.

The Rio, Rivage Intérieur photos mix portraits and landscapes, as well as pictures of private and public spaces. Can you describe your approach to the work, and what you wanted to capture in your images?

The different types of photographs I used are a reflection of the wide scope of the project, and the long time (several years) that I’ve worked on it. Every image—portrait, landscape or detail—has an informative and documentary value as it represents a given moment of life in Rio. But each one of them has a second, more intimate layer that responds to an inner reality: memory, traces, doubts, fears.

This mix of styles and subjects also stems from the use of a large-format camera. Using such a camera dictated a slower approach, but it also helped subverting the classic representation of Rio as a constantly moving city, a tropical maëlstrom. More importantly, I think large-format cameras have a specific narrative quality, as if the stylistic elements of the image became a passage into the understanding of the story. For example, distance becomes a narrative strategy. The city is photographed from the front, which gives the feeling of crashing into a wall and paradoxically, of being forced to wander forever. The same is true for the portraits: in the images of these faces and bodies, you should see the photographer looking at himself, but also the subject looking back at the photographer (in Brazil, the locals unconsciously put a distance between themselves and the foreigners, the gringos).

Last but not least, these empty and undefined spaces, these lonely individuals, these gray skies blurring any certainty also speak of Brazil’s crisis. I started working on this project soon after the end of the blissful years of Lula’s government: one of the most complicated periods followed for both Rio and the entire country. It’s difficult to understand from a foreigner’s perspective, but this is a crucial time for Brazil. The places I photographed, and the people who inhabit them, mirror the country’s disillusionment. Emptiness, silence and wait are the symbols I used to convey the search for a balance to find somewhere between the vanishing of an order and its restructuring.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Rio, Rivage Intérieur?

No, I tried to follow my own lead for this work. It’s a bit of a paradox but I think that when you’re in the process of creating a new project you should be as much receptive of anything that could help move your work forward as you should shut down to the work of others, to avoid the dispersion of ideas. Or at least that’s how it goes for me.

How do you hope viewers react to the Rio, Rivage Intérieur images, ideally?

To be completely honest, I stopped asking myself that question a long time ago. This project is such a personal dialog between me and the people I’ve encountered that I’m not really worried about what people will think of it. Maybe I’m wrong but I’m not looking for the approval of others, I just care about being honest. I imagine some people will like the work, others won’t. C’est la vie.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Literature has inspired me at least as much as photography. For me, a word can be as precise and necessary as an image, or an equally powerful vector of interpretations. I’m thinking about Oceano Mare by Alessandro Baricco, for example. Then there’s cinema: the precise light in Beau Travail by Claire Denis, and the delirious gazes and apocalyptic absurdity of Requiem pour un Massacre by Elen Kimo or Aguirre, the Wrath of God by Werner Herzog.

The first time I discovered photography was in Marseille, in the house of a friend of my father’s where we used to spend the summers. This family friend was made prisoner by the Germans during World War II, and had been in the concentration camp of Buchenwald for 15 months. He became obsessed with that experience, and had a huge library of books on Nazi crimes. When I was about 7, I began to understand what those books were about. Almost all of them had photographs, often portraits of those monsters. I remember I’d look for a long time at those faces, at their eyes; 35 years later, those pictures continue to haunt me. Photography for me is at the same time a tangible and conclusive testimony, but also the start of another story, an object of infinite contemplation that tends towards interpretation.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

I’m an absolute fan of Alec Soth, Thomas Struth et Luc Delahaye. With that said, I realized while working on Rio, Rivage Intérieur that I have progressively stopped looking for inspiration in others’ work. I feel like I’m in a bubble, cut out from the rest of the world, and in any case from all photographic references.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Commitment. Work. Achievement.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2024