FotoFirst — Welcome to Vaziani, a Soviet Utopia Fallen from Grace

Just outside of Tbilisi, the capital city of Georgia, lies an entire district of tower blocks built during the Soviet Era, that not even the Georgians are too aware of. It’s known as Vaziani, and before the USSR collapsed it used to be the privileged home of soldiers serving in the Soviet military. German photographers Arne Piepke and Ingmar Björn Nolting, 25 and 21 years old respectively, have been working on Remains of a Soviet Utopia, a subjective reportage of what Vaziani looks like today: with the soldiers gone, the living conditions in the settlement have drastically deteriorated, pushing its new residents to turn to each other for help and thus create a sense of community.

Hello Arne and Ingmar, thank you for premiering your work on FotoRoom. What are your main interests as a photographer?

AP One of my main interests is to explore and discover something that I previously didn’t know about, and to find my personal perspective on it. I like to become part of and get involved in situations from which I not only learn about my subject, but also about myself. My goal is to create a mood in my photographs that will have a lasting emotional effect on the viewers, to raise questions in their minds and make them think about the subject.

IN My work focuses on long-term documentary projects and portraiture mainly dealing with social and sociological issues. Photography enables me to put myself into contexts I wouldn’t even be able to approach without a camera. Driven by curiosity about how people feel, think, and interact, I try to understand what it means to be human. It gives me an opportunity to relate myself to the world I live.

Where and what is Vaziani, the location at the center of your latest series?

Vaziani is just a 30-minute drive from the gates of Georgia’s capital city, Tbilisi. The rundown tower blocks were built during the Soviet era to serve as accommodations for soldiers stationed at a nearby military base. The military enjoyed several privileges in the USSR: soldiers, especially those in higher ranks, drew a salary and received preferential treatment in housing and supply distribution. Back then, life was good in Vaziani, and the settlement flourished.

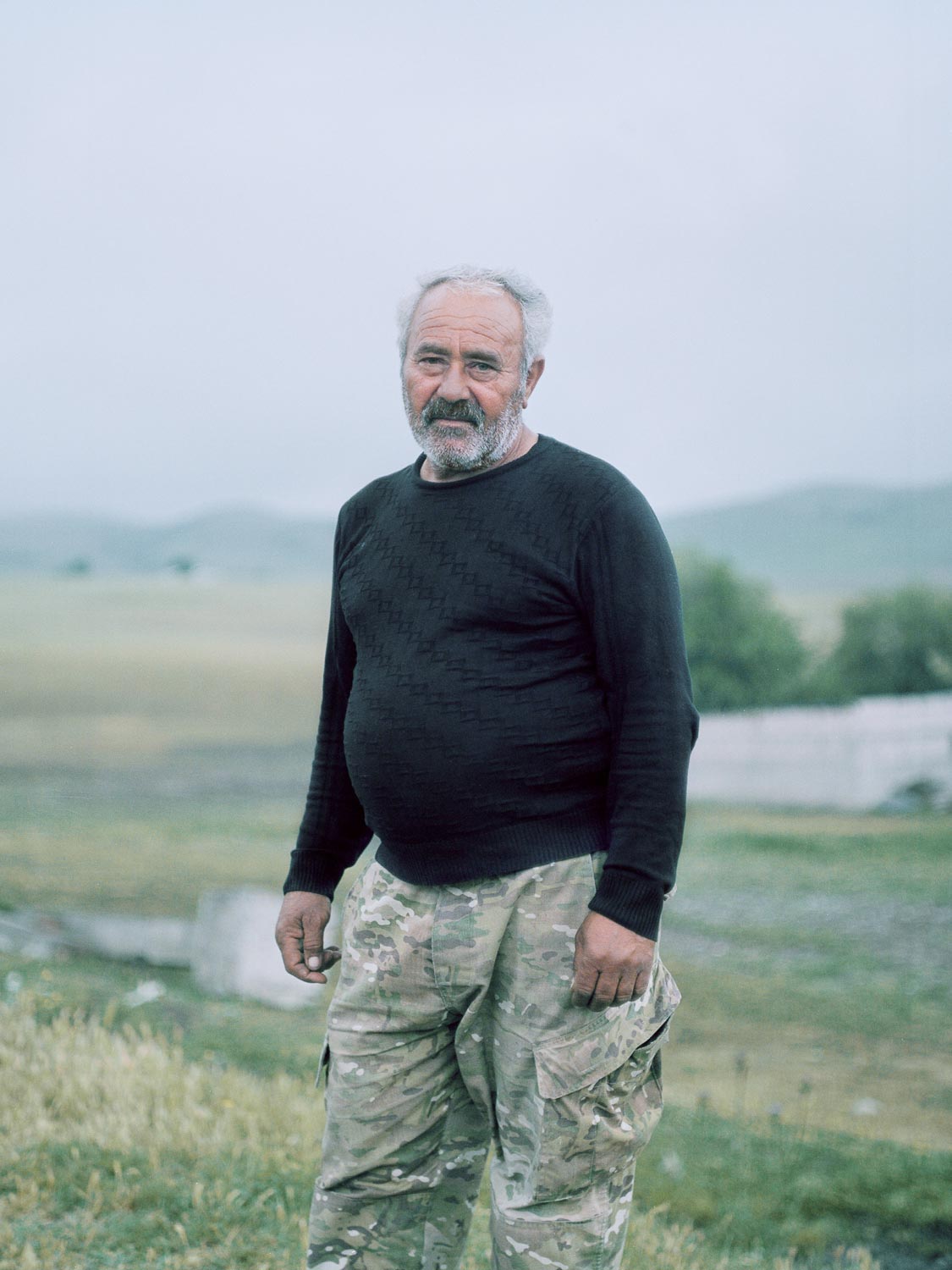

Within four months of the Soviet Union collapse in 1991, the Soviet soldiers and their families had disappeared from Vaziani. Today, the tower blocks they lived in are occupied by people with deprived backgrounds, former homeless and displaced people from Abkhazia. The buildings are in miserable conditions: there are huge problems with the supply of water, gas, and electricity, and twelve buildings are at the risk of collapsing. On the up side, the inhabitants who have to endure these living conditions started to support and help each other, and so a strong community developed.

How did you discover about Vaziani, and what in particular impressed you about it that you decided to make it the subject of your project?

While doing research in Tbilisi we met and got to know Edo, a teenager who lives in Vaziani with his mother. He invited us to his home and during our visit, his family told us a lot about the place where they live. When we realized how Vaziani is an expression of Georgia’s history and current politics, we decided to make it the subject of our work. Edo and his family offered us to stay in their apartment, and even though they did not have much, we were welcomed with great hospitality. Staying with them allowed us to gain the trust of the other residents and participate in Vaziani’s daily life. Elene Eristavi, a friend of ours from Tbilisi, joined us as an interpreter. Her help really pushed our work further.

Can you briefly describe how daily life looks like for the people who live in Vaziani?

Vaziani is geographically quite isolated, which means there are not many leisurely activities to do, especially for the younger generation. Kids usually just gather in the streets to spend their time. Most of the inhabitants are unemployed and in search of occasional jobs. Edo for example has to raise money for his family, because his mother suffers from cancer and is unable to work. He accepts small jobs, like helping local farmers to shear their sheep. Many young people would like to leave Vaziani but can’t because, like Edo, they have to help their parents. Some residents have started to grow their own food, which they then sell at improvised markets and kiosks. Vaziani’s social life revolves around these shops: when the night comes down, they become meeting points to have homemade wine and liquor.

What was your approach to Remains of a Soviet Utopia, photographically speaking? What did you want your images to capture?

We wanted our photo essay to create a strong atmosphere and convey the feeling of what it is like to live in Vaziani. Our visual language is very slow and subtle; some of the photographs speak in a more metaphorical way. Sometimes taking a step back was also a strategy in order to show the bigger context of a certain situation, so it becomes about reading the details. Our representation of Vaziani deals with its inhabitants and their connection to the place they live in, and gives insight into life in Vaziani as we experienced it.

How do you hope viewers react to Remains of a Soviet Utopia, ideally?

We think that there is no such thing as an ideal reaction. Reading photography is always a subjective act influenced by factors like personal encounters, social and cultural background, etc. We hope that people get emotionally involved and interested in this place, which is little-known even in Georgia.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

We are inspired by many photographers, and not only those working with documentary photography. Apart from that, we influence each other quite a lot. Speaking and reflecting about photography with friends has always had a great impact on our work. Both of us study photography at University of Applied Sciences and Arts in Dortmund, so our studies have an effect on our work as well. Besides photography, we are inspired by music, fiction and documentary films, and the people we meet.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Alec Soth, Bieke Deeporter, Zóltan Jókay, Evgenia Arbugaeva, Carolyn Drake, Jitka Hanzlová, Sarker Protick, etc.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

AP Explore. Tell. Reflect.

IN Trust. Patience. Life.

Find out more about Remains of a Soviet Utopia on the project’s dedicated website.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2023