Photographs as Prophesies — Geert Goiris on His Latest Photobook

IN THIS INTERVIEW > Belgian photographer Geert Goiris (born 1971) gives some very interesting background about his latest photobook Prophet, and most notably how he envisioned photographs as ‘prophesies instead of memories‘ for this particular work.

Hello Geert, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I’m interested in the narrative potential still images have. We are so accustomed to and conditioned by camera images that whenever we put a few photographs together, a story seems to unfold. Often these associations between images are based on pre-scripted genre conventions and clichés, this is true. But it is fun to work within the boundaries of the shared image culture we have today, and still try to twist things around a little so there is an element of surprise, a small détournement. The lack of context in a still photograph is also alluring: no sound, no temperature, no before or after. This information deficit can be seen as a point of departure for narrative: it invites the viewer to imagine what came before or after the captured moment.

I also like to play with materials, formats and projectors to find the right physical presence of a photographic image. Lastly, I am still really impressed by the technology and the whole ritual of photographing with a large format analogue camera. It is a slow and costly affair to work with such a camera, but it allows me to move in a very specific way through a landscape, or gives me permission to come up close to a person to make her/his portrait. It is intriguing how these apparatus change our understanding of the world, but simultaneously change the camera operator as well.

The photographs of Prophet, your latest photobook, and the title itself suggest the arrival of something that can’t be seen yet. What inspired you to create this body of work?

I am inspired by what John Berger said: images were initially made to evoke something absent. This observation opens up an almost mystical understanding of the need our species had to invent and develop technologies of image-making. Berger talked mainly about painting, but what is specific to photography is its status as a truthful record of something: it is generally accepted that photos ‘speak about‘ or ‘show’ us a fragment of the past. But what if we would read images as an omen, a sign of things to come? What if we would understand photography as a form of divination, where images are presented in such a way that they can be felt as important signs to be interpreted, as a sort of forecast? In cinema we do this all the time: we are easily transported into narratives that take place in the future, but most photography – by its very nature as a material proof and witness – still anchors us firmly in the past.

Before Prophet, I was engaged in photographing landscapes on the edge of civilization: remote places that can be characterized as wilderness. Unexploited land is becoming increasingly rare. Most of us will only encounter this kind of wild nature in a natural reserve, where it is protected and opened up for a public (domesticated in a way). So these kind of images present us something that is familiar yet remote. While we look at the landscapes we know these places are disappearing. As is often the case, the person or object that is absent will become idealized, colored by our longing to be nearer. These landscapes were exhibited mainly in cities far away from the actual sites where they were taken. The photographs can be the exotic, presenting the idealized other; but simultaneously there is the realization we are witnessing something in the photographs that is not longer present in our reality, so the images shift into the phantasmagorical realm and become fictional. We still long for wilderness (after all it has been in our DNA since the beginning of evolution, so it is not surprising that it still surfaces in contemporary mythologies like Avatar or Interstellar for example) but we know we have lost it. So these landscapes present an absence both in space and time.

In Prophet I wanted to thematize this removal in time even further, not by going backwards and revisiting the past, but by fast-forwarding to a possible future and to imagine the unimaginable: the shape of things to come. Of course this can never be accurate and every attempt is destined to fail, but I saw it as a playful exercise to approach images as prophesies instead of memories.

Prophet uses documentary photographs to create a fictional narrative. Did you have a precise story in mind while working on Prophet, or do you yourself not know what is being prophesied?

My attention goes out to the figure of the prophet. It is someone who belongs to the world and is detached from it at the same time. The success (or following) of a prophet is not so much based on his or her arguments, but mainly on her rethoric powers. Like photography, the style of delivery is important and the urgency with which the message is conveyed makes all the difference.

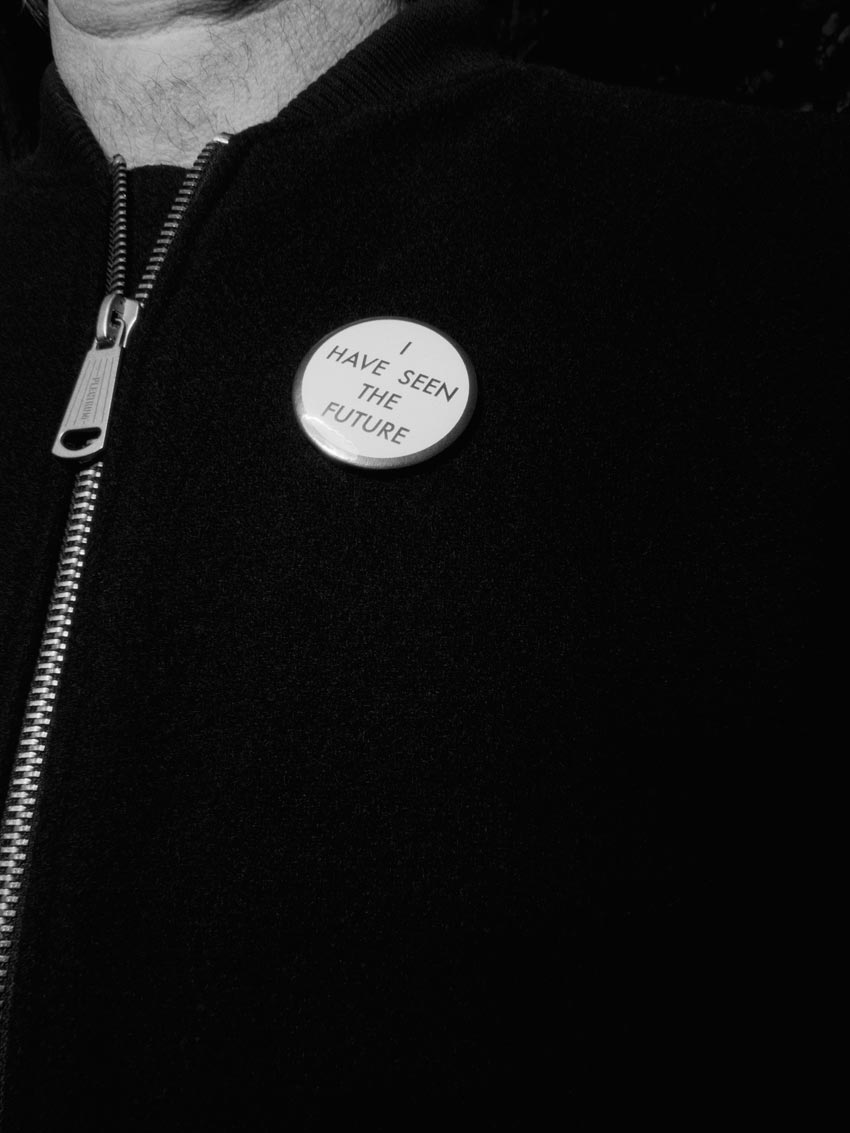

The prophet as an extremely sensitive individual who has the capacity to feel events or trends before they are happening, is in synch with the romantic concept of the artist and the whole notion of the avant-garde. A prophet is a seer. He/she has seen the future and is commanding us to alter our ways. Pretty much like what is happening today in mass media: one of the recurring tropes there is that we are on a path to destruction or annihilation: our current economical, political and social models will not hold. Today’s complexities seem so unsurmountable that it is easier to retort to an apocalyptic narrative. Instead of handing out a manual for revolutionary change or offering solutions, most newspapers and TV stations bombard us with messages of impending catastrophes. Crisis seems to have become a permanent condition, not an exceptional situation.

I didn’t have a precise story in mind, just a vague intuition that a prophet could be an interesting contemporary figure, and that by using this title the viewer would potentially regard the images as projections of things that haven’t happened yet, but presumably will. This kind of compromised futurity is a palpable part of my daily existence in the 21st century.

What themes are you touching on with Prophet? How would you describe the work?

I would describe the work (taking the risk of sounding terribly pretentious) as an attempt to chronicle a certain Zeitgeist or as a subjective psychological portrait of a time that seems to be affected by anxiety and ambivalence.

Can you share some insight into the imagery you selected for Prophet? Are there any specific elements or symbols you used to create the effect you wanted to achieve? For example, children recur in several pictures of Prophet.

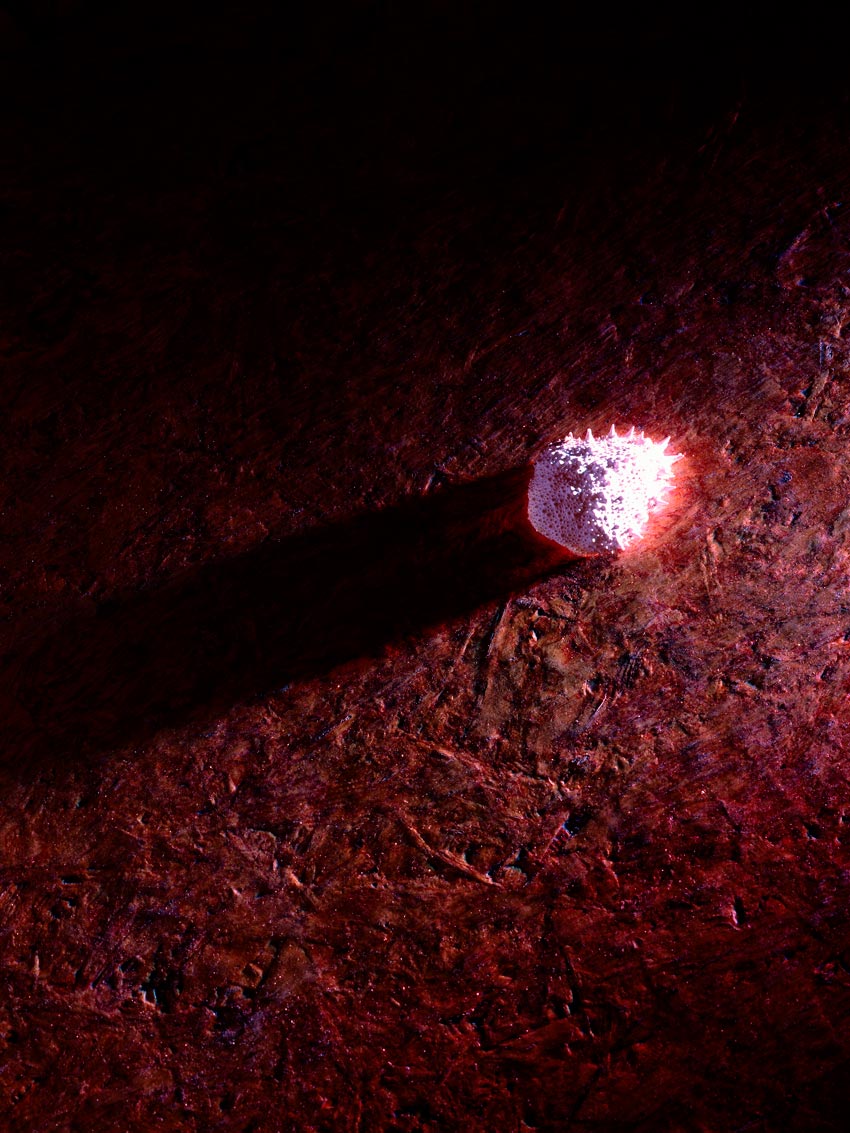

It is my daughter and two sons who are appearing in the photographs. Clearly they represent the future in some way, but a symbol with one singular meaning wouldn’t be very effective as a symbol: we could use a word instead. I wasn’t really concerned with using certain symbols. I just brought the children to a dark Norwegian forest in the midst of winter and asked them to act as if they had to survive on their own. What would they do? When they were ‘in character’ they came up with little scenarios themselves and we worked together on the photographs. It is shot on analogue slide film so we couldn’t check the results right away. (Prophet is a medium format slide projection with programmed dissolves).

Before we arrived, my wife had knitted sweaters for every child, we had bought army fatigues and anoraks from the Norwegian Army overstock to prepare the kids for winter survival. We were playing around with the flashlight and the snow until it got too cold or until we had the feeling we found something visually interesting. So it was more an organic process: we made things up as we went along.

Why did you choose a snowy, natural landscape as the setting for your photographs?

When I grew up in the 1970s and 80s, the majority of dystopic imagination would either be set in an icy snow desert or a hot sand desert – Mad Max for example. Somehow I always felt more drawn to the ice variant, possibly because I grew up in Belgium where we had snow in the winter and my access to sand desert was limited.

Another reason to use Norway as a location was to benefit from the long hours of darkness in wintertime. The prevailing dark background and the use of flashlight made the images in Prophet more theatrical and static. Combining these frozen and still images with the movement of the projected slides slowly fading into the next one has a particular character of its own. I find this form between moving and still images very appealing.

Did you have any specific source(s) of inspiration for this project?

Not intentionally, but a number of times during the shoot with the children the atmosphere felt akin to some passages of Cormac McCarthy’s magnificent book The Road.

For the first time ever, I have included a remake of an existing photograph (not made by me) in my work. The image of the man with the three cigarettes is based on (or almost an exact copy) of a photo that was published in an issue of National Geographic Magazine somewhere in the 1980s. This original photo was published as an illustration of an article about Texas. It showed a researcher in a university campus in Houston doing an empirical test (I don’t know WHAT they were testing), and the article stressed the fact that there is a large scientific community in Houston. Unfortunately I don’t know the photographer’s name. But I love this image so much that I wanted to ‘remake’ it, more than 30 years later.

This kind of re/reading, re/writing and re/visiting of an image is something fascinating. A lot has been said about reappropriation, and this is not my aim at all. In fact, the whole notion of authorship doesn’t excite me much, but I do want to pay some genuine homage (no irony at all, just admiration) to this image by restating it. The original photo was taken by a (very good) photojournalist on assignment: the author was reacting to a situation and ‘hunting’ for striking images. Then 30 years later someone is staging more or less the same situation – but in a studio setting with controlled conditions – trying to copy the light, expression, frame, etc. In the end both images are quite different and have a character of their own. I thought it quite fitting for the book Prophet to restage an event that I only know from a photographic image, and to rephotograph it as a conscious act of time condensing and blurring conventions of chronology.

A large part of photos from Prophet were actually made in the US during a road trip through the plains of Wyoming, North Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa and Illinois, but the atmosphere was very different there. In Norway our little family stayed on a remote hilltop: private and secluded. In the US I traveled together with a friend, we were constantly on the move in a camper. I had seriously underestimated the distances, so there was always a rush to move on to the next destination. The trip was slightly surreal: hours and hours of driving each day over the endless frozen plains, interrupted only by very hurried and slightly paranoid pauses where I would get out the camera, make a few photographs and drive on again.

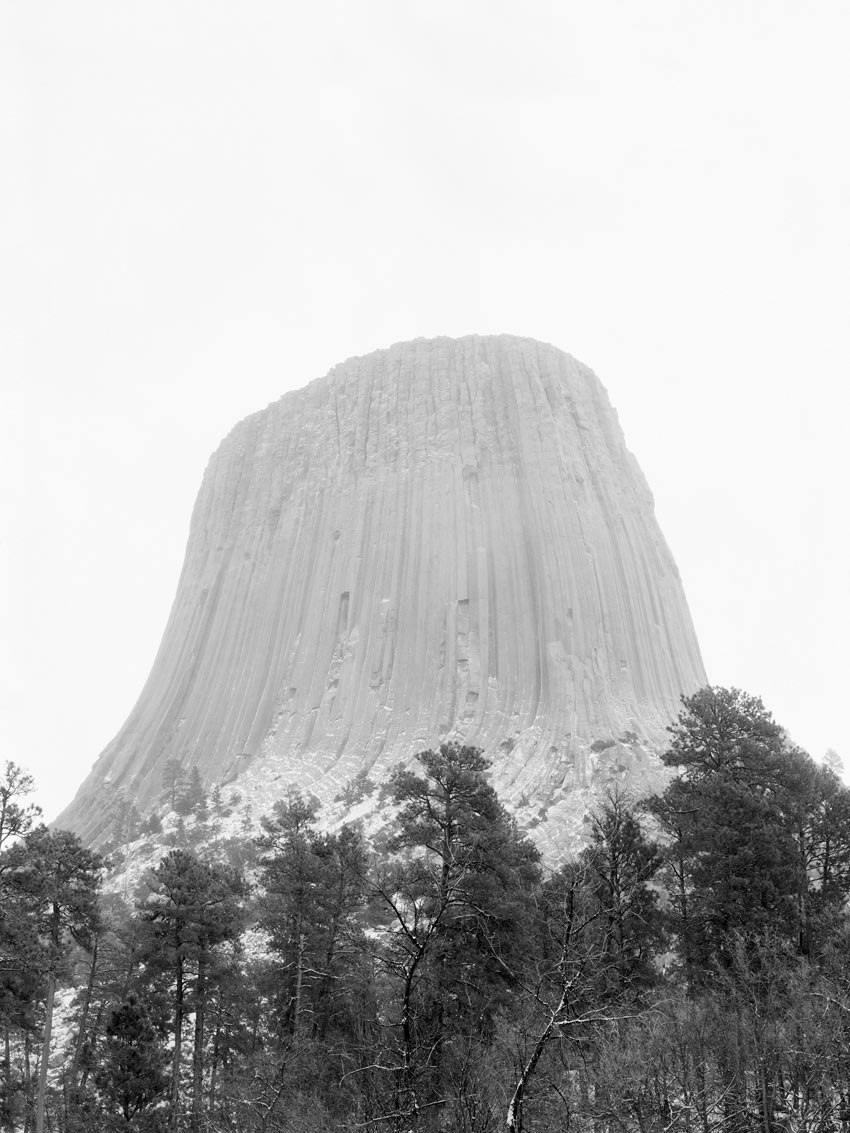

The context of the journey – the companionship, the landscape and the conversations – are as decisive as any other source. It’s a cliché, but most inspiration presents itself unexpected and in strange places. I planned to photograph the Devil’s Tower in Wyoming because it plays such an important part in Close Encounters of the Third Kind by Steven Spielberg (1977). I wanted to see this wonderful geological spectacle with my own eyes, but the reason to include it in the series was to present it as a hint or clue. In the film the shape of the mountain is a recurring motive, a important visual message being received by the protagonist who is unexplicably drawn to this site.

What is photography for you?

Essentially, photography is a proof of existence to me: a kind of incomplete back up. At the same time it is an instrument to decipher some aspects of existence, and for me personally, a tool to build a little archive of meaningful moments.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Portable. Time. Machines.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2023