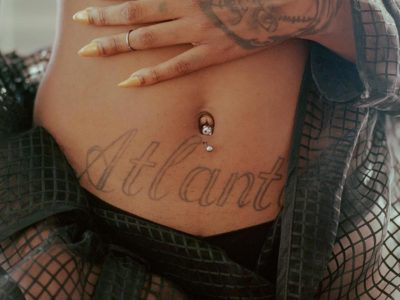

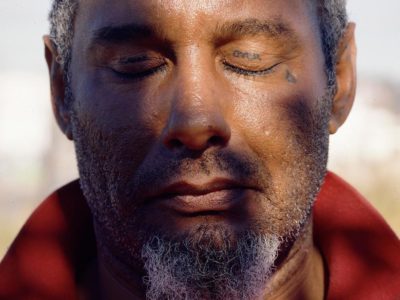

Vincent Desailly’s Photobook The Trap Shows the Communities in Atlanta Where Trap Music Was Born

The Trap by 31 year-old French photographer Vincent Desailly is a photobook recently published by Hatje Cantz (buy your copy). “The book is made of 51 pictures that are linked directly or indirectly to trap music, a style of rap created about ten years ago that has recently become popular around the world” Vincent says. “All the pictures were taken in 2018 in Atlanta, the birthplace of the trap music genre. I humbly consider The Trap an art-documentary project: I didn’t use a photojournalistic approach when shooting, but more of a subjective treatment of a real, tangible, cultural movement and the community that came out of it.”

Vincent had already made work about music when he started out as a photographer: “One of my first assignments, about five years ago, was to document the hip hop community in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. I didn’t manage to get a proper story there but I felt and saw an energy—both musical and visual—that I would have loved to capture, however I didn’t have enough time or experience back then. In January 2018 I caught up with a long time friend, Louis Brodinski, a DJ who got into trap music in the lats years. He’s been going to Atlanta every two months to make music and meet fellow musicians. He suggested I joined him—a couple of weeks later I jumped on a plane. Atlanta reminded me of Baton Rouge in many ways, but on a much bigger scale.”

When he started shooting for The Trap, it took Vincent a while to switch from an editorial to a more personal style: “On my first trip to Atlanta I took the same kind of portraits I do for magazines. I guess the images were good but they didn’t really convey the atmosphere of the place. I usually shoot public figures in hotels or locations they have nothing to do with, so all the first rolls from Atlanta were pictures I could have shot in London, New York or somewhere else. On my second trip I explored the community deeper, used larger lenses, planned less and snapped more. I’m not going to get into the film vs digital debate, but in this particular case the fact that I couldn’t see what I was shooting was very stressful and very helpful at the same time: day after day I forgot what pictures I had already made, so I couldn’t tell myself “you have enough landscapes, close-ups or still lifes.” I just kept on taking pictures instinctively.”

Vincent took one last trip to Atlanta five months after the second one: “I had a few specific ideas of what kind of images I was missing, so in that case I was “chasing” pictures I had in mind. But things didn’t go like I had planned and I didn’t have a chance to make those pictures. I didn’t belong to the community I was photographing: you have to be aware and know when you can take a picture or not. Now I’ve realized that’s just the way it is when you photograph in a certain environment as a stranger, but when I returned home from that last trip I got very frustrated thinking of all the images I couldn’t shoot. I didn’t look at the photos for months. When I finally worked on a first edit it was terrible: I was either picking pictures that had cost me a lot of trouble taking, or choosing images that I guess reminded me of the work of photographers I look up to. The result didn’t make any sense; I soon realized I had to get someone less emotionally attached to the images to take a look. A photographer friend of mine, Louis Canadas, was successful in making a selection that conveyed the feeling I had when I was “drifting” in the trap scene. Half of the pictures in the book are pictures I would have thrown away, and half of my “personal best” are not included; but I think the book shows exactly what I wanted to show.”

Ideally, Vincent hopes viewers will get the contrast between the subjects of his pictures and their environment. “The people I met and photographed in Atlanta have something beautiful and magnetic, while the buildings and interiors they live in look quite rough, which creates a strong contrast. In a way I feel like I can hear this friction in trap music, which is smooth and brutal at the same time, and definitely captivating.” He didn’t have any specific sources of inspiration in mind while working on The Trap, “but the atmosphere of the American South reminded me of Alec Soth’s Sleeping By the Mississippi”.

“I believe more and more that you have to follow your curiosity, what catches your attention and sticks in your head” Vincent says about his practice as a photographer. “I’m not sure I want to take one approach only. I’d like to follow my interests one at a time and use either a documentary or a more fictional approach as I see fit.” The earliest influences on his photography were William Klein and Richard Avedon for “their ability to switch from fashion to portraiture and photojournalism while keeping the same tension.” Other sources of inspiration have been “the balance between darkness and beauty in William Eugene Smith’s work; the strength of Pieter Hugo’s subjects combined with the sensitiveness of his treatment; Alec Soth’s smooth and poetic photography. Recently, I’ve discovered the work of Todd Hido, Philip Lorca diCorcia and Irving Penn. The evolution of Gregory Halpern’s photography is fantastic to follow. Nowadays I’m eager to see any picture by Jamie Hawkesworth. Clementine Schneidermann is also amazingly talented.” The last photobook he bought was Aya by Yann Gross, and the the next he’d like to buy is Polar Night by Mark Mahaney.

Vincent’s three words for photography are:

Obsessions. Contrast. Reflexion.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2024