Arunà Canevascini’s Surrealist Photos Question The Expected Role of Women in Our Societies

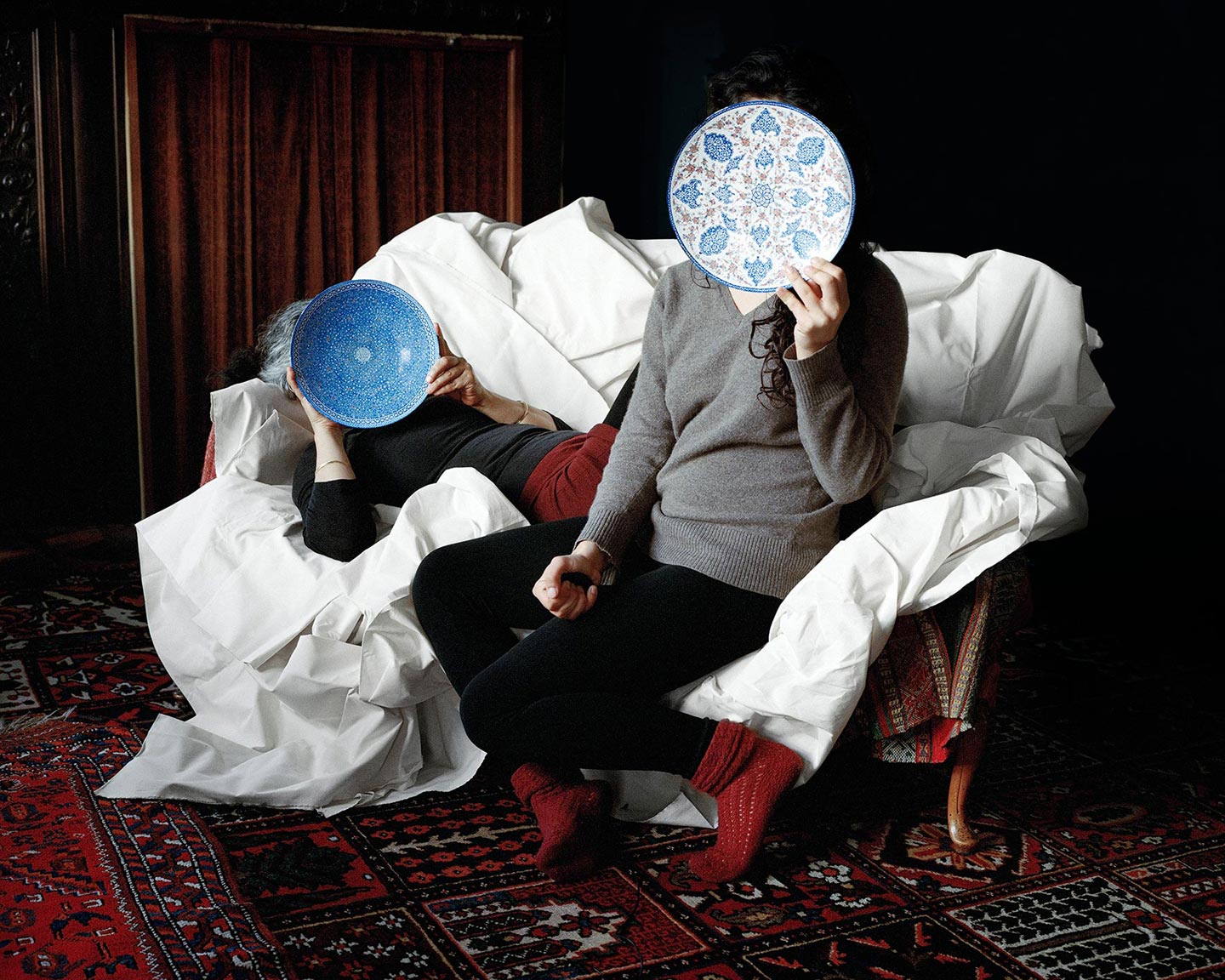

The staged portraits and still lifes in Arunà Canevascini‘s series Villa Argentina are as visually interesting as they are layered with meaning and conceptual ideas. With these images Arunà, a 25 year-old Swiss photographer, is primarily questioning the preconceived role of mothers and housekeepers that women are expected to occupy in most contemporary societies. However, the work also represents an effort at exploring her identity as a part-Iranian migrant: she came to Switzerland as a child with her Swiss father and her mother, an Iranian artist who appears in many of the photographs.

Hello Arunà, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I picked up photography as a teenager, and initially I used it in a very instinctive way, to express myself and have fun. The more I played with it, the more I realized its power as a form of communication: photography can make us see reality from a different perspective, and therefore help us get a better grasp of the world around us. My work is often the result of questions I ask myself, and I hope that those who view it are inspired to start reflections of their own.

Please introduce us to Villa Argentina: what is the work about?

Villa Argentina is a visual exploration of the relationship I have with my mother, set in our family house in the south of Switzerland. My mother is an Iranian artist; she spent her childhood in Tehran as a secluded child, a condition of isolation which she somehow replicates in her adult life. As I grew up in Switzerland, Iranian culture comes to me only as a distant echo.

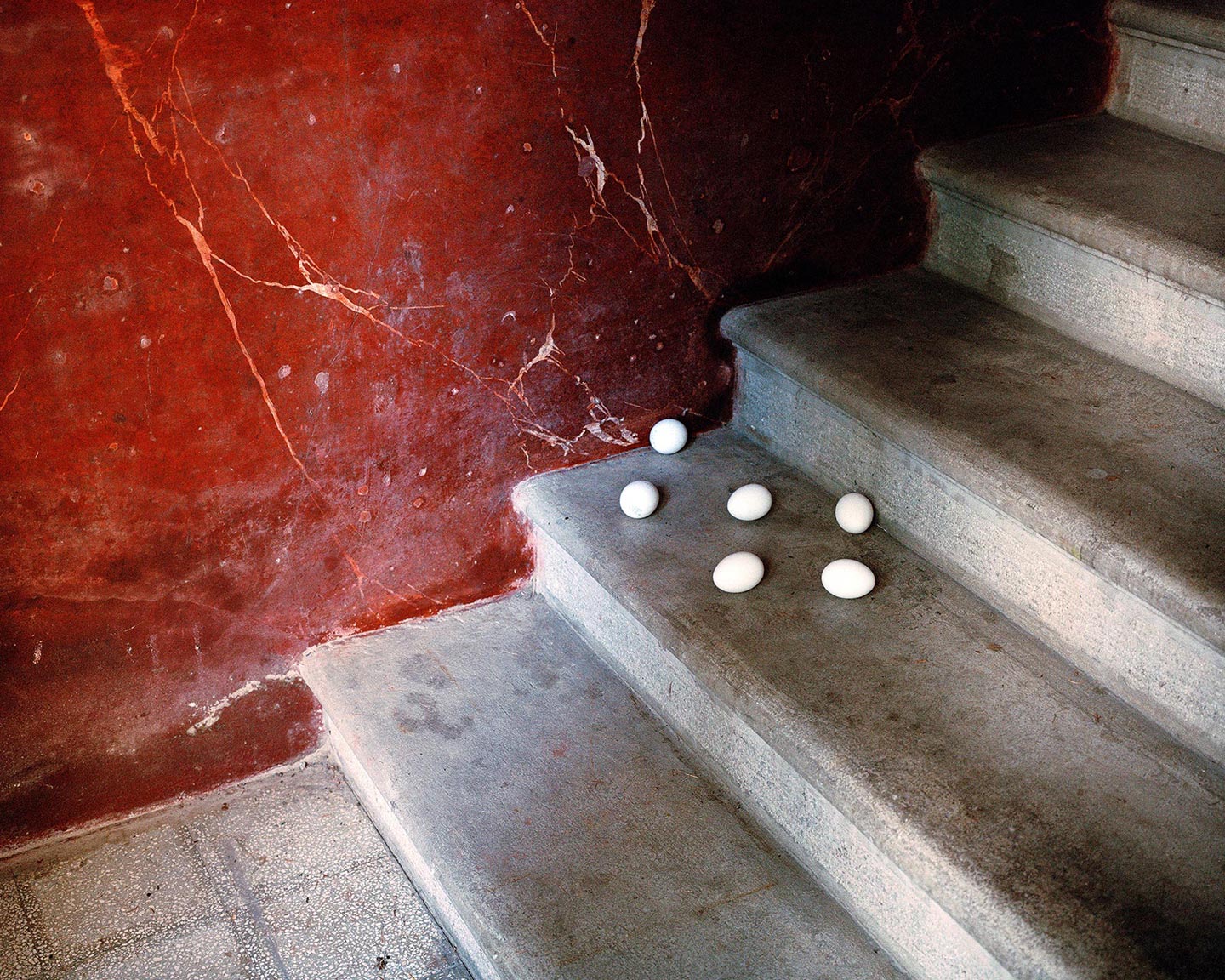

This work uses the Villa Argentina house as a stage for her artistic universe, and a backdrop for the poetic arrangements of objects I made for the camera. In this creative solitude à deux, the series attempts to explore issues of domesticity, femininity and migration.

Tell us a bit more about your mother and your relationship with her.

My mother and I are very close—working with her has been very interesting. She’s been so patient and she often helped me come up with ideas for the series. There were many times I would gather an image in my head that she would then help me bring to life.

What inspired Villa Argentina?

When I was one year old I moved with my family to the south of Switzerland, in a small mountain town with a somewhat narrow mentality. People weren’t used to dealing with foreigners; moreover, my mother cut a quite unusual figure because she was also an artist, and our house has always been a peculiar and bizarre place for strangers.

Whenever I’d visit my friends as a child, I felt their houses were cold and impersonal; and when anyone would come into our house, I felt vulnerable—as if they could discover my deepest secrets. I didn’t like that feeling; I wanted to be like everyone else. In a way, the origins of Villa Argentina are in that sense of being different, which I tried to explore again in the photographs of this series. So Villa Argentina was inspired by my own intimate and personal story, which allowed me to touch on other themes like domestic life, femininity and some aspects involved with migration.

Can you describe your approach to Villa Argentina? What did you want your images to communicate?

With Villa Argentina I wanted to make visible the domestic space—a part of us that is often considered less important than our public lives. I used the private spaces inside the house to create, within the domestic environment, a world parallel to what we normally deem banal and ordinary. The house is often seen as a prison for women, but in Villa Argentina it’s actually a place of emancipation: for me and my mother, our home is and has always been like the stage of a theater where we can freely express and shape our identity.

The project also deals with my cultural background. I’ve always navigated between two worlds: Switzerland and Iran. I’ve never really known Iran; I’ve familiarized with its culture only indirectly, as if it were an echo. I tried to capture some of its aspects in my pictures, e.g. in the photo of the teapots on the tree that metaphorically symbolize Iran—for me, that photo represents exile and migration.

How did your creative process for Villa Argentina look like? What kind of images were you wanting to create?

I believe intimacy has a political side to it, so I thought it was going to be interesting to mix documentary photos showing my personal relationship with my mother; with constructed photos that would deal with more conceptual themes, like what it means to be a woman. This is the case of the picture where my mother is covered with leaves as she holds a vacuum; in that picture I tried to stage, in a surrealist and ironic way, the common idea of what the role of women should be in our societies: the idea that they should be confined to the domestic sphere because that’s where they belong by nature.

Can you talk a bit about how you used the different objects featured in the images?

Some of them are objects we use in our daily life, which I’ve installed to create sets for my photographs. My goal was to construct an alternate, surrealist world as the background to a reinvented role of the woman in a domestic environment, like in the photograph of the leg among the spoons.

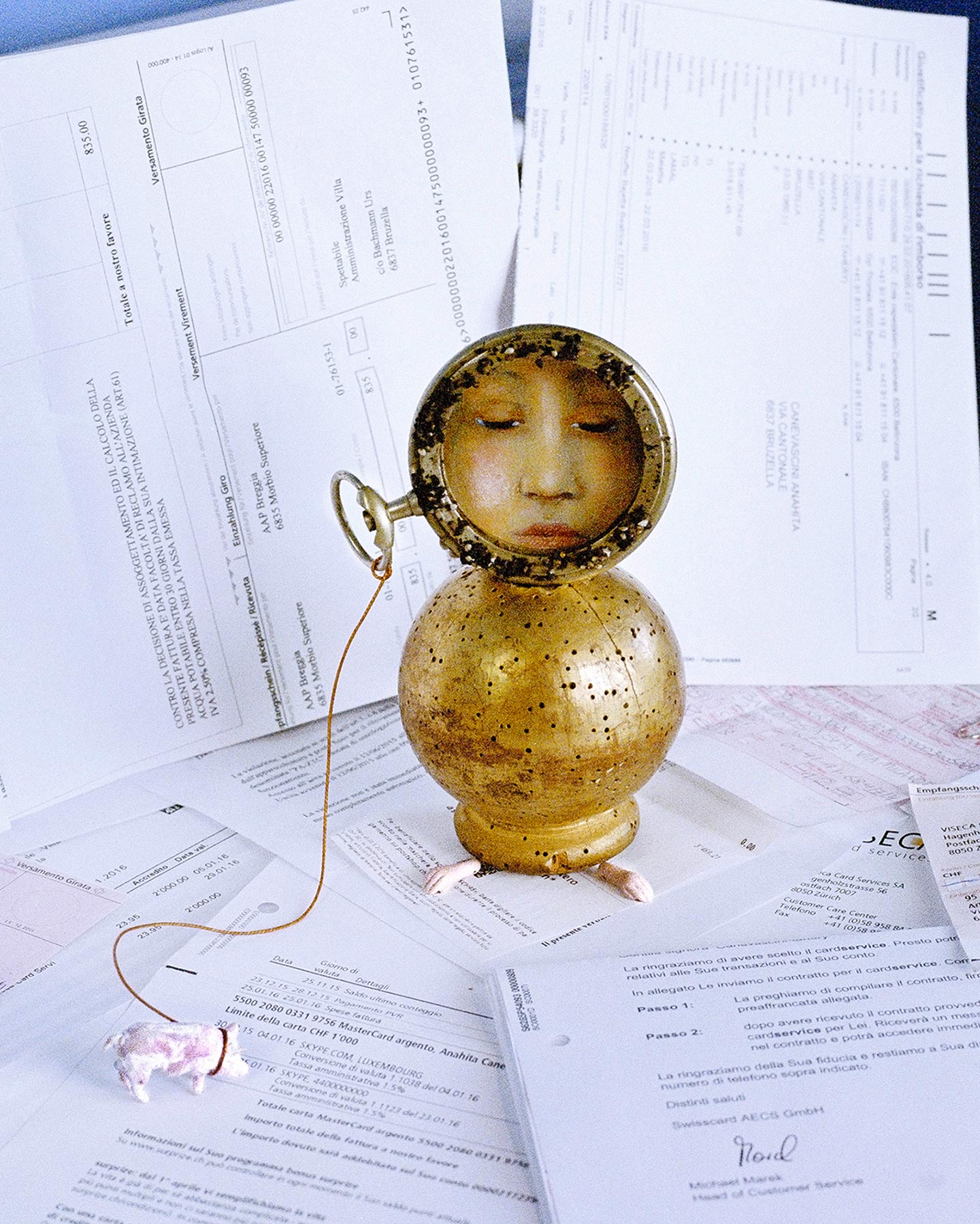

Other objects are sculptures made by my mother that have always been in my house: I’ve decided to photograph them because they are fully a part of our domestic life.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Villa Argentina?

I’m generally very influenced by Dutch painters and photographers; but for this project in particular I studied and researched the visual representation of the Eastern world, and focused on the representation of the Eastern woman in 19th century Western paintings, and in Edward Said’s writings on Orientalism. In one of my photographs, ‘Odalisque with a Pot’, I wanted to question such sexist and stereotyped view of Eastern women: the image shows my mother with her head inside a pot, an item typically associated with housework. My goal with this picture is to show how women have been mostly depicted in the history of art by male artists who have always represented them as idealized creatures, and how society has preconceived ideas on what role women should have, ignoring entirely their individual identities.

How do you hope viewers will react to Villa Argentina, ideally?

I hope Villa Argentina provokes thought in those who see it, and that they are inspired to reflect on some stereotypes maintained by our societies. I wish my images can help them see the world is more complex than it looks.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Duane Michals, Francesca Woodman, Mayumi Hosokura, Luisa Lambri, Alessandra Sanguinetti, Annika von Hausswolff, Tierney Gearon, Gabriel Orozco, Ilu Susiraja, Nan Goldin, Paul Kooiker, etc.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Home. Mother. Daughter.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2024